Women 79

Cuba is Serious and Proactive

VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN

Cuba’s Work is Serious and Proactive

“The leadership that the FMC has today to exalt women before themselves and society is focused on such purposes as: the conquest of women’s autonomy in all areas, the deconstruction of prejudices and stereotypes, against all forms of discrimination and oppression that restrict their development, their freedom and wound their dignity as human beings. This is a strength to fight and do, in an organized and committed way, for non-violence against women”.

Author: Dilbert Reyes Rodríguez | dilbert@granma.cu

August 22, 2020 01:08:10

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Illustration: UN Women Photo: Unknown 2020 01:08:10

Not even the largest catalogue of possible courtesies is enough to erase the trace of a single deliberate act of gender-based violence against a woman.

Calling such acts abhorrent does not accept a single minute of debate. It is more important to make better use of all the opportunities – highly potential – that we, as an organized country, and with a declared political and governmental will, have to proactively and speedily confront the scourge.

It is well known that there are cultural roots that complicate and prolong this war’, that there are different, concrete and subjective obstacles, and it is also well known that there are hunters of the naïve who are betting on taking advantage of these slopes in order to push Cubans against each other under the skin of sheep and in order to divide us.

President Díaz-Canel himself has repeated it: “In matters of law and society, they have not given up on the search for points of rupture in national unity, magnifying the possible dissent on sensitive issues such as egalitarian marriage, racism, violence against women, or the mistreatment of animals, to mention a few, in all of which we are working seriously to resolve centuries of debt that only the Revolution in power has faced with unquestionable progress.

There will be no lack of those who, once again, contract with the hackneyed accusation of “politicizing everything”, in order to distract the arguments that explain, clearly and from within, that the country is not sitting idly by on an issue as sensitive as violence against women. But since there are words that have their backing in deeds, Granma tackles the issue with Dr. Mayda Alvarez Suarez, director of the Center for Women’s Studies (CEM).

-How have actions been taken in recent years to reduce violence against women?

-There have been many debates over these years, with the aim of making the existence of violence against women in our country visible and understanding its causes, combating stereotypes and placing the issue in the development of essential policies. Important experiences of orientation, prevention, telephone help lines and protection programs have also been carried out in different territories; but we are far from feeling satisfied because we cannot forget that the phenomenon has deep roots in the patriarchy, in societies characterized for centuries by the existence of unequal, unequal and power-based relationships. It is still there, manifested in thought and relationships in couples, families, workplaces, public places, where it is not always perceived as such, nor confronted and attended to as it should and is necessary.

“Male chauvinist concepts, prejudices, sexist stereotypes persist and are reproduced in our society, anywhere and at any level, and although there have been changes in assessments and ideas about violence, which were found by the National Survey on Gender Equality – conducted in 2016 by CEM, the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC) and the Centre for Population and Development Studies of the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI) – we were also able to reveal which ones remain, continue to hinder further progress and are at the root of existing inequalities.

“At present, the vast majority of Cubans do not justify violence against women or men, nor do they blame women for acts of violence (mistreatment or rape) and reject the idea that women should bear it.

“However, in a part of the population there are still criteria that contribute to sustaining and perpetuating violence against women. The most entrenched are: alcohol consumption is the cause, the woman who endures the abuse is because she likes it, most women withdraw the complaint, and consider the violence a private matter. These criteria become justifications for not intervening or denouncing the acts of violence”.

-Are there results that allow us to characterize an effective advance in the reduction of violence against women?

-The First Conference of the Communist Party of Cuba, held in 2012, before the National Survey was carried out, had already declared that there was a confrontation with prejudices and discrimination of all kinds that still persist in the heart of society. In particular, in its objective No. 55, it explicitly states that it will “raise the level of rejection of gender and domestic violence and that which is manifested in the communities.

“Among the main achievements of the current phase, the new Constitution of the Republic stands out, which expands and strengthens the protection of rights, particularly those of women and girls.

“The recognition of the right to a life free of violence (Articles 43, 85 and 86), the commitment to address it, ratifies the importance of prevention and enhances the mandatory responsibility of the State in the implementation of legal standards, public policies and the improvement of protection mechanisms for victims. At present, a process is under way to harmonize the new articles of the Constitution with various legislations that will allow its effective implementation, for example, the modification and updating of the Family Code, which will be brought to a process of popular consultation and referendum. The Criminal Code is also being analysed and amendments are being suggested.

“The Standing Committee on Children’s and Youth Affairs and Women’s Rights of the National Assembly of People’s Power is an important ally in promoting compliance with the Cuban State’s agenda for the advancement of Cuban women and in monitoring its implementation.

“In order to assess the progress made in reducing violence against women, better records are needed of the acts of violence that are detected and dealt with, and of their follow-up and solution. Ongoing statistics are needed to make it possible to compare, over time, the increase or decrease in cases, the prevalence and incidence of violence in a given population, and its frequency and severity, among other indicators.

“There is also a need to carry out periodic surveys on violence against women, which would allow for its systematic evaluation in selected periods and data of international comparability”.

-How much more do you think can be done, under the current conditions, to accelerate the change of such behaviours in the country?

-Above all, it is urgent to perfect ways, procedures, mechanisms, protocols of action in the institutions involved and everything necessary to attend, immediately, with respect and without prejudice, to the victims of violence, and to apply the law rigorously to those who commit these acts.

“Improving the presence of the subject in the laws in force, which are currently in the process of being modified, is also very important. However, my personal opinion is that we would benefit from a specific and comprehensive law on violence against women, which contemplates all the measures and sanctions that already appear in existing laws, and others that need to be enacted.

“Regarding macho conceptions and stereotypes, everything that is done to generate transformations in subjectivity is key: creative communication products, adequately focused from a gender perspective, training courses, community and face-to-face debates, the use of social networks

“Essential is the training in gender and violence to decision makers and lawyers because of the importance of their role in this issue, the insertion in curricula, in the training of educators, communication specialists, among other actors.

“Exchanging experiences with other countries, both to research and to confront and address in practice these facts, adapting them to our context, is also very useful, since violence against women is a global problem.

“On the other hand, the FMC has valued the need to increase the confrontation to the facts of violence in the communities, from our base structures and, for that, to raise the level of training of our leaders and collaborators of the Women and Family Orientation Houses. From the fmc, we have always affirmed that the most important thing is not that there are many or few of them, but that whenever there is a woman who is violated, she is well cared for and her rights are defended.

-What strengths exist to confront this?

-We have the political will of our Party and Government. The confrontation with violence is endorsed in the programmatic documents of the Party and in the Constitution. Instruments such as the Family Code, which was approved in 1975 and is in the process of being modified as I mentioned earlier. There’s also the National Plan of Action to follow up on the agreements of the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1997, contain principles and actions to guarantee gender equality and non-violence.

“The educational and employment opportunities enjoyed by women, as well as access to free and universal health services, including sexual and reproductive health services, have placed Cuban women in a better position to achieve autonomy and independence, which weakens the chances of experiencing situations of dependence and having to endure, for that reason, situations of violence.

“The safety and protection of sons and daughters is also guaranteed. The State provides free education for the offspring, their food and systematic medical care, with no gender differences. Thus, for example, girls show as high percentages of education as boys. There are also institutional support mechanisms for low-income families, especially for single mothers.

“The leadership that the FMC has today to exalt women before itself and before society is focused on such purposes: the conquest of women’s autonomy in all areas, the deconstruction of prejudices and stereotypes, against all forms of discrimination and oppression that restrict their development, their freedom and wound their dignity as human beings. This is a strength for fighting and doing, in an organized and committed way, for non-violence against women”.

Our Women

Our Women

In keeping with these times, more than 130,000 women have joined the urban agriculture movement and the medical brigades that have gone out to fight the pandemic in other nations, 61% of whom are women.

By Yenia Silva Correa

August 5, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Photo: Rodríguez Robleda, José Raúl

From economic and productive work, continuation of the work to support the fight against the pandemic and stops to pay homage and recognition, the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC) is promoting a group of activities to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the organization, which will take place on August 23.

With strict adherence to the health measures required by the complex epidemiological situation caused by COVID-19, it was reported this Tuesday, through a press conference, that the program on the occasion of the event will have the communities as its setting.

Teresa Amarelle Boué, Secretary General of the organization and member of the Political Bureau, reminded [everyone] that the main challenge that the new coronavirus represents today does not diminish the protagonist [leading role, wl] of Cuban women in the other challenges they lead. These include “maintaining what has been conquered in terms of gender equality, that there are no setbacks in the midst of the new forms of economic management that the country is promoting, the situation of the aging population and how to perfect the protocols of action to confront gender violence in our country.”

JOY AT NATIONAL HEADQUARTERS

Excited, after the news of being the vanguard of the country, the FMC of Santiago de Cuba dedicated to the FMC’s founder, Vilma Espín, the condition received.

“We could not go to Segundo Frente, to pay her any other tribute than this one, obtained in the midst of the current complexity”, declared Elena Castillo Rodríguez, provincial secretary.

In addition to the leading role played on the health front, she highlighted the massive incorporation of food production in agriculture and on industrial estates, the demand for discipline in public spaces, the active promotion of electricity saving, and the implementation of more than a hundred training programs for women who are not working.

I’m Not Who You Think

spectator’s chronicle

I’m Not Who You Think

By Rolando Pérez Betancourt

By Rolando Pérez Betancourt

July 12, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

After 35 years of sustained triumphs in various films, French actress Juliette Binoche is once again shining in her latest film, which will soon be shown on Cubavisión.

I’m Not Who You Think (Safy Nebbou, 2019) is the story of a divorced, 50-year-old literature professor with two children who uses the tricks of Facebook to create a profile that turns her into an attractive 24-year-old blonde.

The causes and consequences of this change will be the main theme of this romantic drama with a thriller-like twist. It’s conceived in the midst of human relationships conditioned by technology and the masks that encourage so-called catfishing, or [creating a] non-existent identity in social networks with the aim of attracting unwary people.

In days of unbridled love passions on Facebook, Twitter and Whatsapp, director Safy Nebbou waves the trump card of Binoche and squeezes it into the role of a middle-aged woman trapped in the obsession of feeling wanted. Why not fall in love with a young man much younger than she? And the protagonist embarks on the adventure, even if she ends up in the hands of a psychiatrist. This is a resource that is used from the beginning to weave the threads of the story in two stages and thus expose the intimate worlds of a woman who, after the divorce, was exposed to the risks of depression.

The film takes a critical look at the lies and manipulations of social networks and is a treat for viewers to reflect on issues such as the fear of growing old, the age difference when it comes to love, and whether it “looks good” for a mature woman to go crazy with love (and delude herself into madness), as she would have done in her twenties.

We will then see an exceptional Juliette Binoche fall silent, when a young lover tells her that she could well be her mother; chat in the solitude of her home, pretending to be the little girl she is not; fall into the chaos of uncertainty and moral collapse; shine like a sun and explode into childish euphoria when she feels wanted.

The film is all of her, and also a story of loneliness on days when it seems that everyone is connected.

A Motherhood Story

JR Podcast: A Motherhood Story

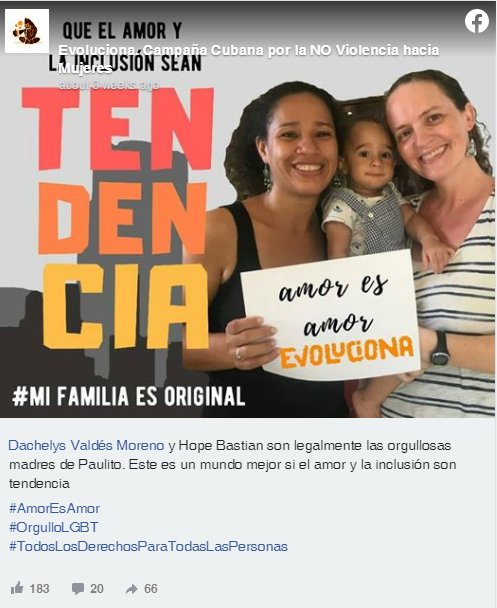

On this occasion, JR Podcast spoke with Dachelys Valdés and Hope Bastian, who were recognized by the Cuban state as Paulo’s mothers. Read on and listen to the story.

By Dailene Dovale de la Cruz

By Dailene Dovale de la Cruz

digital@juventudrebelde.cu

July 20, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Dachelys Valdés and Hope Bastian, mothers of Paulo Author: Courtesy of the source Published: 20/07/2020 | 06:07 pm

Dachelys Valdes and Hope Bastian were returning from Florida with a concern. Would the pregnancy test be positive?

They met in Cienfuegos, in 2015, during the First National Meeting on Gender Studies and Non-Heteronormative Sexualities. They fell in love. They started a relationship and when they saw it consolidated, they decided to have a baby.

The first thing they did was consult their family doctor. He, kind and diligent, investigated the possibilities of accessing assisted reproduction services and returned the bad news. They could not access the service because equal marriage was not yet recognized in Cuba.

Nor did they find other options. Or yes, but in extremely risky ways.

A friend could pretend to be a partner of one of them, but what if he claimed his rights as the biological father? So many possibilities for disaster: divorce, death. They didn’t want to live in fear. They traveled to Florida with a very deep longing. On their way back they had a little boy in Hope’s belly.

Hope’s name is equivalent to our Esperanza that symbolizes very well the feelings of both women, when they got off the plane on Cuban soil.

Photo: Courtesy of the interviewees

In Cuba, the birth certificate was slightly changed. The doctor, without anyone getting in the way, crossed out the predetermined male figure and wrote down Dachelys’ name. A small but significant gesture.

Dachelys Valdés is grateful and remembers this stage fondly. They attended the consultations with an in vitro fertilization specialist, no matter where it took place. They did not receive any discriminatory treatment, nor did they feel vulnerable, she confesses. And those who listen to her voice, very clear and soft but not docile, regain their faith in a more inclusive, less prejudiced and homophobic nation.

At the polyclinic, when they were going to be tested, they often tried to look for some sign of embarrassment in it. When they made it clear that they were the accompanying couple, they said “ah, it’s all right”, without further reaction.

Paulo was growing up in Hope’s womb in a calm and happy environment.

Photo: Courtesy of the interviewees

That was a collective pregnancy, the two first-time mothers were accompanied by fathers, brothers, friends.

That group of loving and supportive people has grown over time. I learned part of their story from a teacher at my school, Rocío Baró. One afternoon, at the end of 2019, she told me about the procedures both mothers took to obtain the Cuban citizenship of their little boy. She spoke with such great admiration of these two women that I promised myself to learn more about them, their experiences, their careers and their joys.

The desire became palpable in mid-June. I was checking Facebook, almost like an automaton, when the news came out. “The Cuban state legally recognizes that Paulo has two mothers.”

It had been worth the effort of the trip, for Dachelys to study how the birth would be, but in English. The losses in terms of comfort, being away from much of her support network.

…

Paulo’s citizenship is still an ongoing project, but it is getting closer. They have a document from the Ministry of International Relations, which endorses the possibility of access to the childcare center and free health services.

They also have a birth certificate, which guarantees double maternity, for the first time in Cuba. They arrived at great happiness, free of fear. The process of obtaining such a certificate was slower than usual for families made up of both parents.

First, they started the procedures from Florida, they sent the documentation by post and the certified translation. They returned with their child on a family visa, because it was more feasible to carry out the procedure from Cuba. They knew that due to the newness of the case, the process would take time. They did not expect it to be around a year, nor did they imagine a pandemic. Instead, they confess to being safe and grateful for the end result, of not being left behind.

Photo: Courtesy of the interviewees

Since the announcement of their happiness, Dachelys and Hope speak a lot, to anyone who wants to know their story. They tell how they managed to realize their pregnancy and the remaining steps so that their child, for example, can have access to the food in the ration book. They feel that by telling of their experiences they make the LGTBIQ+ community more visible, the need to recognize the diverse forms of family, the access to assisted reproduction by same-sex couples, eliminating stereotypes. To recognize love and commitment as the only requirement to form a family.

They would like their story not to be isolated, not only for couples with resources and access to treatment in another country, although they understand that the laws and social sciences need reality to knock on their doors. And they are ready to continue, with every knock and every step, to bequeath to Paulo a more inclusive and happy Cuba.

Photo: Courtesy of the interviewees

These are some excerpts from this story. If you want to hear from the voice of Dachelys Valdés and Hope Bastian, the emotions, fears, unforgettable moments, just listen to our podcast. Don’t miss it! [in Spanish]

Women’s Faces and Actions

Women’s Faces and Actions

In Santiago, 17 women serve as sector chiefs of the National Revolutionary Police (PNR)

By Odalis Riquenes Cutiño

July 18, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

“If women build, how can we not be able to maintain order in the neighborhoods,” says First Lieutenant Evelyn Blanco Cadalzo, in charge of sector No. 102, in the Jose Marti Urban Center Author: Jose Angel Morales Published: 18/07/2020 | 10:24 am

SANTIAGO DE CUBA. For eight years now, the days of the young first lieutenant of the National Revolutionary Police (PNR), Evelyn Blanco Cadalzo, have had the duration of the surrender, the imprint of the sense of duty.

That’s just how long since she graduated from the former Interior Ministry (Minint) Hermanos Marañón University, as a law graduate specialized in public security. Since then, she has been the head of Sector 102 of the First Station, popularly known as Micro Nueve, in the José Martí urban center.

She has under her jurisdiction Blocks A and B of the José Martí Sur Popular Council, a community where she was born and has lived for her 27 years. It’s an area which, although not complicated in terms of criminal potential, is a recipient of criminals from other parts of the city who come there to commit offenses and crimes, such as robbery with force and theft with violence.

Preserving order in the place where you were born, where you have your friends and everyone knows you can be difficult if you are not clear that when duty calls, it is the first thing to be maintained: “You have to have character, set limits well and show that things done badly should not be seen by anyone anywhere in the world.

At the beginning of the year, this novel member of the PNR showed her courage and professional stature by getting involved in what could be considered the most notorious case she has ever been involved in: the capture of an escaped rapist, whom she had to protect from an angry mob with no other shield than her own body.

Hours earlier, as part of her operational work, she learned of the occurrence in her popular council of the reprehensible act against an eight-year-old girl,. Her first admitted thought was for his three-year-old daughter, Hasly Emely Estiven Blanco. She even thought about what she would do to that monster if she had it in front of him at that moment.

Later, chance gave her the opportunity to support her partner in charge of the investigations in the case, first sub-officer Luis Salmón Borrero,. After a long time of tracking him, when she found the offender in the middle of a crowd trying to lynch him, she reacted as she was taught in the ranks of the Cuban Police and took him out at the risk of her own life, protecting him until she could drive him.

“At that moment I felt it was my duty to prevent that man from being attacked. Cuba is a state governed by the rule of law and no one can take justice into his own hands; that is what the law is for,” she stressed.

Evelyn’s daily routine knows about beginnings, but never about the time of return, and even less about what each day will bring: “You know that you start work at 8:00 in the morning, the rest is dictated by the day. Sometimes you think: I’m going to have a little meal at home today… and in the end, you can’t because you have to do a search, an operation, or you get information that you have to deal with immediately. That’s why I’m so grateful for the support of my husband and my whole family, especially in caring for our daughter.

It is common to see her correcting, explaining, orienting, preventing the same thing in her office, in Block J of the José Martí district, or in the area for self-employed workers next to the shopping center in Block B. She considers it her “red zone” because everyone has a license, but some persist in selling industrial products that constitute illegalities.

Whoever observes her realizes that she knows how to be firm and energetic, without losing her tenderness. Her walk is filled with the authority and respect that she has earned through her daily performance.

“The work of the sector chief is very rewarding. At the beginning, it can be cumbersome, but once you organize it and get to know the factors of the community, you realize that it is among the best specialties of MININT, because it allows you to communicate with people”.

Everyday heroines

The experience of First Lieutenant Evelyn Blanco Cadalzo is not unique in Santiago de Cuba, where 17 women, mostly young, work as sector chiefs in the PNR stations.

Being a woman and leading a sector does not imply any additional limitations, insists Evelyn Blanco. “It used to be seen as something rough, but not anymore. Today people in the community accept it, take it as something normal, which we can perform successfully. If women can build, how can we not be able to maintain order in the neighborhoods? Everything is in the heart and the dedication you put into it; that’s how you earn respect.

However, there are still hurdles to overcome in the experience of First Lieutenant Gretchen Pérez Delgado, sector chief at the 30 de Noviembre Popular Council. She goes out every day to combat illegalities in an area plagued by many important economic objectives and a very diverse population.

“Each day brings complexities. Sometimes people on the street think that because you are a woman you are not going to do your job and they try to look down on you. We have shown that we can do this work, and in fact, we do it with the same quality as men,” insists this energetic girl, the mother of a two-year-old girl.

For First Lieutenant Tamara García Cala, chief of sector No. 62, in the community of PetrocasasSalaíto, in the Abel Santamaría Urban Center, without the support of the family it would have been impossible to get the job done during her two and a half years of service.

So does Lieutenant Reyna Nápoles Fabré, who heads Sector 55, which covers the San Juan area. Her two children and her husband have been instrumental in her performance. With 29 years of service in the FAR and MININT, she walks without fear at any time in her territory: “Being a police officer is my pride, and I really like the work as head of the sector because every day you learn about the human being and their social performance.

“I try to enforce what is established, but always reaching out to people. Every day I get up at 5:00 in the morning to be early in my area. The first thing I do is visit the community factors, get interested in the social reinsertion of some who are on probation, for example. Explaining, giving arguments, are keys to achieving the transformation of people, emphasizes Naples Fabré.

During the last three months, the rigors of the confrontation with COVID-19 in the slums added new tasks for these community heroines. For more than ten hours, the first NCO, Yenis Pereira Batista, sector chief in the Abel Santamaría neighborhood, risked contagion until she was able to transfer a suspected case of SARS-CoV-2 to the hospital.

“Usually,” she says, “I stay more at work than at home, and in this health situation, I have been almost always in the Sector, walking the area, visiting families and verifying that the measures are being complied with. When we see that we were able to contain the epidemic, without being confident, it is comforting to know that it was worth the effort.

This satisfaction is also felt in many communities in Santiago and in other provinces, where the population lives its daily life with confidence because they know that women and men of the stature of the interviewees defend the order and tranquility of the citizens in their neighborhoods and streets.

Assisted Reproduction Options

Roads are Opening Up

The Assisted Reproduction service combines various techniques to achieve a pregnancy when something prevents it from occurring naturally. It is an expensive specialty and demands technology, both for the diagnosis of the obstacle and for its solution

By Mileyda Menéndez Dávila

July 14, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

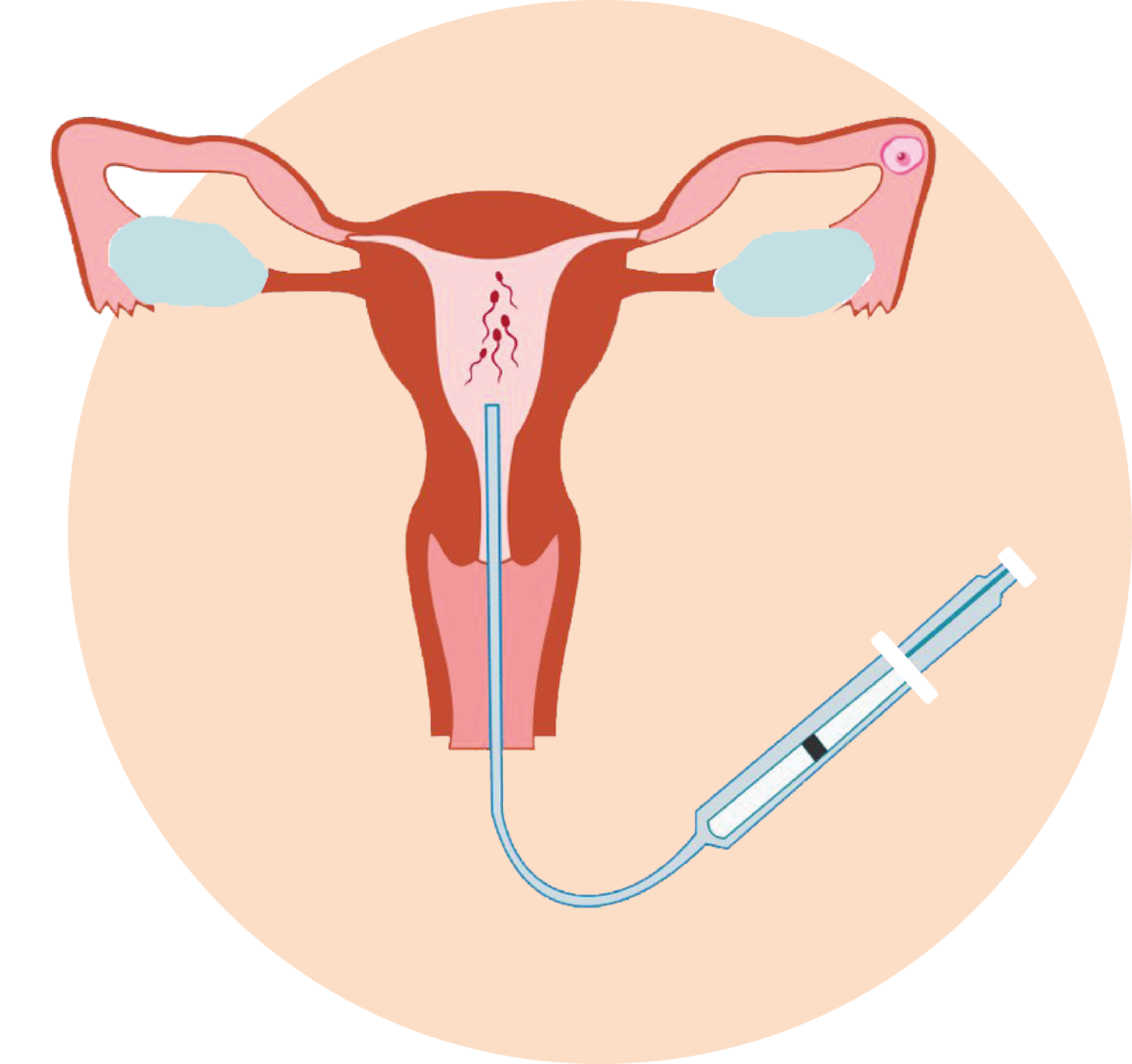

Assisted Reproduction Author: Juventud Rebelde Published: 14/07/2020 | 11:04 pm

The Assisted Reproduction (AR) service combines various techniques to achieve a pregnancy when something prevents it from occurring naturally. This is an expensive specialty that demands technology, both for the diagnosis of the obstacle and for its solution.

High-tech options

Vitro Fertizization (IVG) requires an authorized laboratory for the sperm to fertilize the oocytes in a controlled environment. In less than a week, viable embryos can be transferred to a woman’s uterus to follow the natural course or frozen.

It is a complex, laborious method; only a quarter of the transfers are effective. The number of attempts depends on the number of embryos achieved.

There are classic IVF (the environment is created and the cells are activated) or by intracytoplasmic injection (the sperm is inoculated directly into the cell). In Cuba the first one is done.

Low-tech options

The most common technique is artificial insemination (AI): a catheter is used to deposit a concentrate of previously purified sperm in the uterus and fertilization is expected to occur. It can be fresh or frozen semen.

Depending on the link between the recipient and the donor, the AI is homologous if there is a marital relationship, or heterologous when the sperm comes from a bank (guaranteed, but anonymous).

The technique is simple and its complications are very low. The probability of success is between 15 and 25 percent, but several attempts can be made. High-tech options

In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) requires an authorized laboratory for the sperm to fertilize the oocytes in a controlled environment. In less than a week, viable embryos can be transferred to a woman’s uterus to follow the natural course or frozen.

It is a complex, laborious method; only a quarter of the transfers are effective. The number of attempts depends on the number of embryos achieved.

There are classic IVF (the environment is created and the cells are activated) or by intracytoplasmic injection (the sperm is inoculated directly into the cell). In Cuba the first one is done.

In vitro fertilization Observation of the embryonic development day by day

Embryo transfer to the uterus

The technique is simple and its complications are very low. The probability of success is between 15 and 25 percent, but several attempts can be made.

Solidarity childbirth

An increasingly common option for overcoming obstacles is surrogacy: a healthy woman is inseminated or lends her womb to receive embryos, and then hands over the baby to the person or couple who will raise it.

Examples of solidarity are the donation in sperm banks and giving embryos to other women when the desired number of children has been reached and they are available. Countries should regulate these processes because of the ethical and legal implications for their participants.

More than infertility

The AR is a useful service for very diverse users:

– Couples who are infertile due to a health condition detected in one or both of their members.

– Couples with no apparent obstacle that has tried for a reasonable time and does not achieve the desired pregnancy.

– Persons who wishe to exercise maternity or paternity without another parental figure in the upbringing.

– Couples of the same sex who depend on a donor or supportive womb.

– A person whose circumstances prevent the materialization of coitus or the assumption of parenthood and who wants to preserve his or her reproductive cells for more opportune stages. This has been the case for artists, sportsmen, people deprived of their liberty, with high-risk jobs or under medical treatment that compromises their fertility.

When Violence is Defined with Symbols

When Violence Against Women is Defined with Symbols

By Ania Terrero

By Ania Terrero

Cubadebate journalist. Graduated in 2018 from the Faculty of Communication of the University of Havana.

On Twitter @AniaTerrero

July 16, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

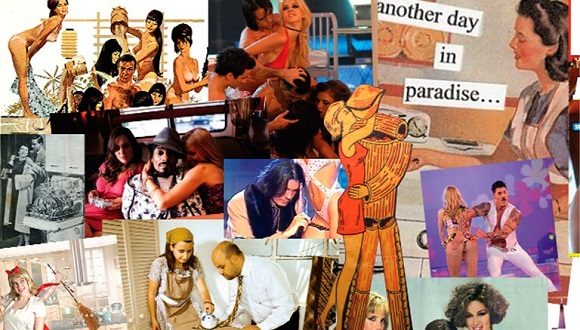

Sexist stereotypes are repeated ad nauseam in the media and cultural industries. Photo: Sophia.

Media that accuse, simplify or ignore victims of gender-based violence; others that silence inequalities. Soap operas that show women concerned about their relationships, motherhood and only later, sometimes for professional fulfillment. Video clips with abundant shots of almost naked dancers, offering their charms to the artist in charge. Advertisements where, while they cook, wash and dream of ideal household appliances, they drive luxury cars and manage life beyond the home.

The list is long: sexist stereotypes are repeated ad nauseam in the media and cultural industries. Over and over again, patriarchal principles are naturalized [socially “acceptable”] according to which women should be beautiful, sensual and delicate, take care of household chores and children, fulfill the sexual desires of their partners and belong to men. They perpetuate, in short, other forms of abuse, although this time in a symbolic way.

In the words of the French theorist Pierre Bourdieu, symbolic violence refers to a group of meanings imposed as valid and legitimate by the patriarchal culture, which are based on male supremacy and domination and, therefore, have a close relationship with power and authority. But the conflict is more complex and has many forms.

As explained by the journalist, professor and expert in gender issues Isabel Moya, in her article From Silence to Media Show, this phenomenon implies “the reproduction in the mass media, and in general, in the cultural industries of a sexist, patriarchal, misogynist discourse that relies on prejudices and stereotypes to present reality and social processes in all areas: the productive and reproductive, the public and the private, the basis of the economic structure and the socio-cultural superstructure”.

In other words, a kind of vicious circle is produced in which the makers of these discourses validate and transmit myths and macho images which, in turn, they inherited from previous generations. By the work and grace of the latent patriarchy, stereotypes persist and are amplified as informative, audiovisual and entertainment alternatives grow.

This happens, moreover, in a world where a relatively small group of transnational companies dominate the information and entertainment market. Conglomerates such as AOL-Time Warner, Disney, Sony, News Corporation, Viacom and Bertelsmann dictate the what and the how. They decide what global audiences will see, hear and enjoy. In short, a few decide for many and influence them.

The greatest danger lies in the fact that, directly or indirectly, they tend to naturalize a gender-biased construction and a subordination scheme where women play at a disadvantage. As a result, it contributes to reproducing the causes of male violence against women and girls.

“The media establish, through their discourses, an axis of cultural matrices, where the hegemonic power is made explicit and reproduced. They constitute one of the mechanisms of reproduction of the patriarchy on the level of subjectivity,” Moya said.

In relation to the above, symbolic male violence must be analyzed in a broader context. As the journalist specializing in gender issues, Lirians Gordillo, explained to Cubadebate, feminism and gender theory had the clarity to demonstrate the interconnection between different forms of discrimination. “The relationship between patriarchy, capitalism and racism, among others, as systems of oppression, allows them to be sustained and updated,” she said.

Therefore, symbolic macho violence is accentuated and acquires particular nuances when other categories such as skin color, place of residence, sexual orientation and gender diversity are involved. It is vital to recognize these forms because they allow us to identify zones of silence where it grows and intensifies.

Abuses that are hidden from view

The first step in dismantling symbolic male violence is to learn to identify it, but this is rarely easy. It often takes more subtle forms than physical, economic, sexual and even psychological. Moreover, it happens in a world of cultures and words where norms are not always clear, where almost everything is considered valid and where, therefore, feminist demands are often assumed to be excesses or exaggerations.

This phenomenon goes beyond perhaps obvious manifestations, such as the objectification of the female body and the re-victimization of those who suffer gender-based violence. Many times, it begins in apparently simple expressions such as silence or absence. The fact that many of the inequities and discriminations that women face today do not usually appear in the media and in entertainment products is a form of abuse.

In the opinion of Lirians Gordillo, because of the fact that what is not named does not exist, removing women with diverse identities from the public stage means not seeing them as people with rights.

“In the Cuban case, we are not talking about women in an abstract concept, but about those who are marked by other features such as skin color, age, gender identity, sexual orientation or the presence of a disability. Perhaps the most absent are transsexual women, lesbian women and black women,” she said.

Addressing gender conflicts from a lack of knowledge, reproducing the stereotypes that make them possible, is as serious, if not more so. According to Isabel Moya, these issues have gone from being “what is not talked about” to being illuminated by the spotlight.

However, she explained, “the lights only illuminate some issues: violence against women, abortion, marriage between homosexuals or lesbians… But more than true light, what prevails, with its honorable exceptions, is the banal approach, the morbidness, the sensationalism that becomes yellowish in some cases. Commonplaces that support myths and stereotypes are repeated ad nauseam”.

And there goes another form of symbolic violence that is almost never evident. Sexism, prejudices and macho representations dominate a good part of the informative and leisure production in the world where we move. They validate a model where women, in more or less obvious ways, are subordinated to men, depend on them or, when they try to make a difference, are excluded. These problems do not only affect them, but also all those who break with the moulds of an essentially conservative society.

Video clips and songs that depict women as objects of desire, films that sell stories where violent men fall in love with nice girls and these girls do their best to save them from themselves, advertising that outlines the roles assigned to each sex and promotes an unattainable ideal of beauty, comedy shows that ridicule homosexual relationships, sensationalist headlines and the stereotypical treatment of gender violence that gains space in the media are just some examples of this phenomenon.

Moya mentions others: “Symbolic violence is exercised when women of the South are treated with folkloristic or xenophobic approaches; when love between women is blamed; when so-called ‘women’s issues’ are confined only to certain sections of newspapers or newsreels; when the lyrics of a song cry out to the four winds to ‘punish’ it; when the protagonist of a series for teenagers only lives for her ‘perfect physique’ and we see her multiplied in dolls, T-shirts and disposable cups”.

The persistence of a sexist language, which privileges the use of the masculine as a universal generic, evidences other forms of macho abuse in the symbolic realm, said Gordillo. This goes beyond written or oral expression and is manifested in other ways in audiovisual products. “We have to analyze what the conflicts of women and men are in series and films, in what roles they appear, and what relationships they establish between themselves,” he added.

Cuba, realities and challenges of a latent violence

Although the work of training and education on gender issues among journalists, communicators, artists and creators has already begun to bear fruit, Cuba does not escape the examples and consequences of symbolic violence.

According to Lirians Gordillo, in audiovisual production, with a few exceptions, a patriarchal representation of women persists. The usual conflicts and interests for them are still the traditional ones: family, couple relationships, aging. Even when they have an active public and professional life, the problems associated with it are subordinated to the previous ones.

As Cuban researchers have pointed out, the public arena is one of the main spaces of progress for Cuban women. “They tend to have greater participation and representation in decision-making in different spheres, but patriarchal relations still prevail within the domestic sphere. It is very curious how this reality is represented in fiction, soap operas and other products,” said the journalist.

At the same time, research on the Cuban press has detected challenges and obstacles that still limit the treatment of issues related to macho violence, human trafficking, feminist struggles, inclusive language and good ways of doing gender journalism.

The last ten years have made some differences if we are talking about symbolic violence. For Gordillo, if one analyzes the informative and entertainment production in that period, one finds more professionals within the communication interested in breaking with macho stereotypes and more communicative products that assume diversity.

This shows the possibilities of a real change and its consequences. However, he said, the majority of products continue to reproduce symbolic violence, even, sometimes, with the intention of being inclusive and not reproducing stereotypes.

According to the journalist, good intentions are not enough because the way we look, the visual codes, the construction and representation of that reality have been formed and educated from the patriarchy. “We have to unlearn many stereotypes, many representations and many macho codes. That needs knowledge, it takes a process of questioning, of getting out of comfort zones above all,” she said.

In this way, filmmakers, artists and communication professionals must combine personal preparation with the use of advisors and specialists when building works and products that approach these issues. Even in those who do not touch on gender conflicts directly, prior training is necessary because these issues usually cut across any representation of society. Alliances between academia, research, communications and artistic creation are vital.

Diversity and systematization of communication products that address male violence is another key point. “Due to its complexity, this problem cannot be analyzed in a single communicative product, once a year or in a specialized media. It is a conflict that needs to be discussed, represented and deconstructed in a systematic and diverse way,” said Gordillo.

Male violence and its expression in the symbolic realm is an urgent challenge. It limits and threatens women’s lives and their rights, but it also affects the development of the nation. Therefore, the best possible response will be one that combines social, political, legal, educational and health efforts, among others, and is articulated as a comprehensive policy. In short, the country we want to be is also at stake.

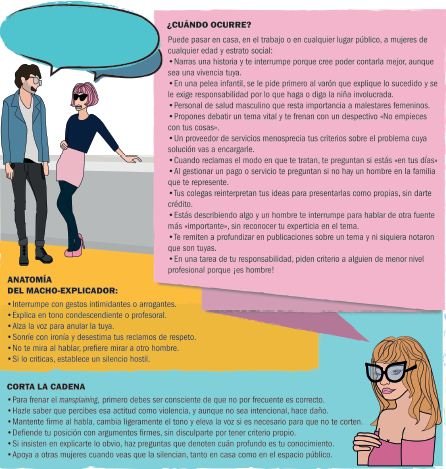

I can explain myself!

I can explain myself!

The habit of speaking up for women and belittling what they do or say is a sometimes unconscious form of male violence

Published: Wednesday 08 July 2020 | 12:10:47 am

By Mileyda Menéndez Dávila

By Mileyda Menéndez Dávila

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Let me shut up about your silence.

–Pablo Neruda

Have you noticed how many times a man explains to a woman or a girl something she already knows, often in an affected tone? That attitude is a type of micro-machismo that since 2008 is identified with the term “mansplaining” (its literal translation would be “macho-explanation”), and it is a typical [form of] gender violence, a patriarchal mechanism that takes away from the value of the female experience in order to silence it.

It can be an unconscious act, transmitted for centuries through diverse cultural channels. When it is brought to their attention, some revise their attitude and try to unlearn it.

CHART (Translation)

WHEN DOES IT HAPPEN?

It can happen at home, at work or in any public place, to women of any age or social status:

You tell a story and he interrupts you because he thinks he can tell it better, even if it’s an experience of your own.

In a children’s fight, the boy is first asked to explain what happened and is held responsible for what the girl involved does or says.

Male health care workers downplaying female ailments

You propose to discuss a vital issue and you are stopped with a derogatory ¨no start with your stuff¨

A service provider disregards your opinion about the problem whose solution you are going to entrust to him

When you complain about the way they treat you, they ask you if you are ¨on your days¨

When arranging a payment or service you are asked if there is not a man in the family to represent you

Your colleagues reinterpret your ideas to present them as their own, without giving you credit

You are describing something and a man interrupts you to talk about another source ¨más importante¨, without acknowledging your expertise on the subject

They refer you to deepen your publications on a subject and they don’t even notice that they are yours

In a task of your responsibility, they ask someone of a lower professional level for his judgment because he is a man!

Anatomy of the macho-explicator:

Interrupts with intimidating or arrogant gestures

Explaina in a condescending or professorial tone

Raises his voice to cancel yours

Smile with irony and dismiss your demands for respect

He doesn’t look at you when he talks, he prefers to look at another man

If you criticize him, he establishes a hostile silence

Cut the chain:

To curb male chauvinism, you must first be aware that not because it’s often right

Let him know that you perceive that attitude as violence, and that even if it’s not intentional, it hurts

Stand firm when speaking, change your tone slightly and raise your voice if necessary so that you are not cut off

Defend your position with firm arguments, without apologizing for having your own viewpoint

If they insist on explaining the obvious to you, ask questions that will show how deep your knowledge is

Support other women when you see them being silenced, both at home and in public spaces

Violence Against Women

MINI-DICTIONARY FOR TODAY’S WORLD

Violence Against Women

The intention, expressed or underlying, in this type of violence is to control the woman, to deprive her of dignity, self-esteem, autonomy and voice; thus, she is modeled as an extension of the man and all her value lies in the union of beauty and utility, her “respect” for the rules that are pointed out to her, her obedience and her disposition to fulfill basic tasks: home order, accompaniment, pleasure and reproduction

Author: Victor Fowler | internet@granma.cu

May 29, 2020 00:05:36

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Violence is a problem that concerns everyone, so silence makes us complicit. Photo: Taken from the Internet

This is the name given to the set of attitudes, actions, expressions, speeches and devices of all kinds that aim to control, humiliate, degrade or cause physical, moral, economic, sexual or psychological suffering or harm to a woman just because of her condition. It is a constitutive characteristic of relationships of domination-submission and those who participate in the process occupy the roles of victimizer or victim.

The intention, expressed or underlying, in this type of violence is to control the woman, to deprive her of dignity, self-esteem, autonomy and voice; thus, she is modeled as an extension of man and her entire value lies in the union of beauty and utility, her “respect” for the rules that are set forth, her obedience and her willingness to fulfill basic tasks: home order, companionship, pleasure and reproduction.

The manifestations of violence against women can be either continuous or discontinuous, refined or crude, subtle or evident, charged with anger and the application of physical force (pushing, hitting) or psychological and expressed through silence, disinterest or the devaluation of what the woman thinks or feels. The above-mentioned devices cover all areas and moments in the victim’s life and are presented as a mixture in which there are – acting in conjunction – elements of prevention, “education”, surveillance, control, blackmail, discipline and punishment.

Although the extreme cases (beating, physical attack, rape or femicide) become public – thanks to the intervention of the Law and the mass media – most violence against women is “naturalized” and takes place in the public space, in situations of apparent normality, or “inside” the families, where there are no witnesses. Violence against women denies women the right to decide what kind of intervention they want or accept, what forms of social exchange and even what limits.

Examples of the above are actions with a sexual content such as compliments, unsolicited physical contact, harassment and sexual aggression; discrimination (direct or indirect, at work or otherwise) due to the status of women; threats with respect to child support or power, and the dynamics of patriarchal and androcentric authoritarianism in the family, the workplace or any place in public space and society.

Bibliography consulted (main sources)

El género en el derecho (Gender in Law). Ramiro Ávila Santamaría; Judith Salgado and Lola Valladares (compilation). Quito: Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, 2009.

Gamba, Susana- Diz, Tania. Diccionario de estudios de género y feminismos. Buenos Aires: Biblos, 2007.

Jokin Azpiazu Carballo. Masculinities and feminism. Barcelona: Virus Editorial, 2017.

Straka, Ursula (coordinator). Gender violence. Caracas: Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, Posgrado Área de Derecho; Amnesty International; Reforma Judicial, 2015.

Cuadernos de género: Políticas y acciones de género. Training materials / Marta Aparicio García; Begoña Leyra Fatou and Rosario Ortega Serrano (eds.) Madrid: Instituto Complutense de Estudios Internacionales, 2009.

70% Increase in Gender-Based Violence

Chile Reports 70% Increase in Gender-Based Violence During Quarantine

The Chilean Government is preparing a set of measures to expand the network of support for women victims of gender violence from government and business bodies

April 7, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Minister Carolina Cuevas explained that Chilean women need to ask for guidance and help when they are victims of domestic violence. Photo: Taken from Telesur

The Ministry of Women and Gender Equality in Chile reported on Monday a 70 percent increase in calls made by women to a domestic violence hotline during the first weekend under quarantine in the country following the health crisis generated by the coronavirus.

The information came to light as part of a study provided by the minister of the portfolio, Carolina Cuevas, who implemented a contingency plan that included special reinforcement of the Fono Orientación 1455 shifts, to protect women who reported being subjected to domestic violence.

The weekend before the quarantine, 532 calls were received, while in the same period, one week later, the number rose to 907. “This significant increase in calls is also a reflection of the fact that there is a need to ask for guidance and help in times when women are spending more time in our homes, possibly with our partners,” Cuevas explained.

For its part, the Public Prosecutor’s Office reported that, although reports of domestic violence have decreased by 18 percent compared to last March, reports of femicide have increased by 200 percent in the same period of time.

The Chilean government is preparing other measures to expand the network of support for women victims of gender violence, such as coordination with public agencies to safeguard care in periods of emergency, increasing the capacity of shelters and a messaging service, via SMS or WhatsApp, so that women can communicate in a “silent” manner that will be implemented in the following weeks.

Cuevas also met with the president of the employers’ union, the Confederation of Production and Commerce (CPC), Juan Sutil, to discuss the impact of the health crisis on women workers. The minister requested that companies provide formal support to women in preventing domestic violence and incorporate the issue into their permanent policies.

In this regard, a group of Chilean women legislators and feminist organizations sent a letter to President Sebastián Piñera, asking him to strengthen measures to prevent violence, to prohibit the sale of alcohol that can trigger violent acts, such as creating immediate action groups and establishing strategies for reporting violence through websites, pharmacies or supermarkets. Gael Yeomans, MP and president of Convergencia Social, said that additional measures should be taken to allow victims of gender-based violence to break out of quarantine if they need help.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | ||

You must be logged in to post a comment.