Movies 28

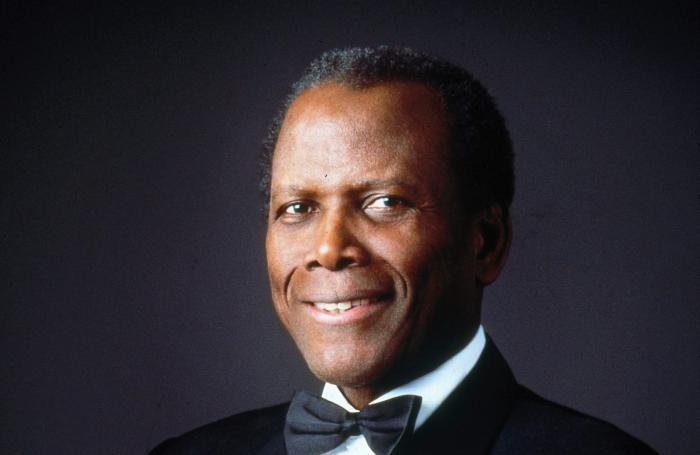

Great actor Sidney Poitier dies at 94

Great actor Sidney Poitier dies at 94

He was the first African-American actor to win an Oscar (Lilies of the Field, 1964), becoming a symbol of Hollywood during the civil rights movement.

Author: International Editor | internacionales@granma.cu

January 8, 2022 11:01:58 AM

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Photo: hipertextual.com

Sidney Poitier, the first African-American actor to win an Oscar (Lilies of the Field, 1964), has died at the age of 94, becoming a symbol of Hollywood during the civil rights movement, a period in which he became the biggest star in the American film industry.

The death of Poitier, who was also a civil rights activist and diplomat, was confirmed by Clint Watson, Press Secretary to the Prime Minister of the Bahamas.

CNN and the German agency Deutsche Welle do not specify details about the death of the legendary actor, born in Miami in 1927 and whose parents were natives of the island of Cat.

In addition to the Oscar, Sidney Poitier received two Oscar nominations, ten Golden Globe nominations, two Emmy Award nominations, six Bafta nominations, eight Golden Laurel Award nominations and one nomination for the Screen Actors Guild Awards.

Following the death of Kirk Douglas in 2020, Sidney Poitier was one of the last survivors of Hollywood’s Golden Age. In addition to an incredibly prolific acting career, between 1997 and 2007 he also served as the Bahamian ambassador to Japan and was on the board of Disney between 1995 and 2003.

He acted in some 50 films, the most important of which include Fugitives, Porgy and Bess, Paris Blues, To Sir, With Love, Lilies of the Field and In the Heat of the Night. In the 1980s and 1990s, his activity slowed down but many will remember him for his performance as Donald Crease in Sneakers, released in 1992 alongside Robert Redford, Dan Aykroyd, Ben Kingsley, Mary McDonnell, River Phoenix and David Strathairn.

He also directed nine films, many of them comedies, in the 1970s and 1980s. Uptown Saturday Night is probably the best-known. From his success, Sidney Poitier directed two more related films that are considered a trilogy: Let’s do it again and A Piece of the Action, all three with Bill Cosby.

Censorship and freedom of expression

Censorship and freedom of expression

In 2017 first, and then in 2019, authors Tom Secker and Matthew Alford obtained declassified documents from the CIA, the U.S. Department of Defense, and the National Security Agency detailing the extent to which these institutions were involved in American film projects

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

“There are themes that are not for laughs, neither are they for that school of filmmaking that brings Agent 007 to life.” Photo: Still from the Agent 007 films.

When James Bond producer Harry Saltzman seemed to be giving Costa-Gavras, after his first success, a blank check, saying: “What film do you want to make?”, he replied: The Human Condition, by André Malraux. The man cracked right there and then: “What? You need a lot of Chinese people, you can’t do that”, and closed the subject with a laugh.

Costa-Gavras confesses that at that time he was interested in films precisely about the human condition, about revolutions, daily struggles, the workers’ movement, the unions. At some point he worked on the project of making a feature film about Malraux himself, then deGaulle’s minister of culture.

There are subjects that are no laughing matter, nor are they for that school of filmmaking that gives life to agent 007. It’s risky to say the latter when thinking of Malraux, a man whose list of brave deeds, during the French Resistance and before, make him perfect legendary material for Ian Fleming’s literary creativity. However, I can’t imagine Bond writing something like The Human Condition. There is in the Anglo-Saxon character too much cheap philosophy, caricature of Nietzsche’s superman. Much less do I see Bond ending up being anyone’s minister of culture, no matter if it is the French warlord, or if it is Josef Stalin.

There is another more important reason that differentiates Malraux’s characters from Bond. The former seek with (futile?) desperation the simultaneous redemption and understanding of the sense of being in the face of the immeasurable anguish of having to kill. The latter assumes to his condition of existence a brute quality of polite murderer. It is known that originally the Bond character was to be a blunt weapon, lacking sophistication, with the mere function of murdering by the orders of another. That license to kill is really a license to carry out assassination orders and take the occasional macabre liberty.

The founding director of the CIA, Allen Dulles, was a friend of Ian Fleming. After the Bay of Pigs debacle, the agency sought in the fourth installment of the Agent 007 series of films, Thunderball (1965), a public relations operation to improve its image. It introduced a character, Felix Leiter, a CIA agent, as an empathetic character. The sympathetic agent, an employee of the agency promoting coups and political assassinations in so many parts of the world, lasts to this day.

In 2017 first, and then in 2019, authors Tom Secker and Matthew Alford obtained declassified documents from the CIA, the U.S. Department of Defense and the National Security Agency detailing the extent to which these institutions were involved in American film projects. The list totals 1,000 titles, including film and television material, and includes many of the most iconic products of American filmography.

According to Secker and Alford, in many cases, if there are “characters, scenes or dialogue that the Pentagon does not approve of, the filmmakers have to make changes to accommodate the military’s demands.” At the extreme, “producers have to sign contracts – production assistance agreements – that tie them to a version of the script approved by the military.” To make the reality even more interesting, in most cases, the agreements reached and the intervention of U.S. Government agents in a film product is confidential, protected by corresponding contracts. Not that they like it to be known out there that they are systemic censors, the public defenders of free speech: it is not a happy combination to support their employees or co-optees in other geographies as victims of censorship, and at the same time appear to cut scenes from films because the nuance is contrary to the imperial machinery.

In Goldeneye, Brosnan’s debut as Agent 007, an incompetent Yankee admiral who is killed by the bad guys, was not to the military’s liking; as a result, the unhappy character’s nationality was changed to Canadian and so appeared in the final product. In Tomorrow Never Dies, another installment of the British spy saga, some scenes were altered or deleted to please the uniformed censors. The CIA is more subtle (of course!), sometimes inserting its own employees in the writing of the scripts to avoid having to go under the knife later.

But beyond certain anecdotes, the involvement of imperial agencies is more systematic than cutting scenes or altering scripts. It is not just that “the idea of using film to blame mistakes on isolated, corrupt agents or bad apples, thereby avoiding any notion of systematic, institutional criminal responsibility, is straight out of the CIA and Pentagon manuals,” as Secker and Alford assert. The agencies of imperialism give made-in-U.S. entertainment an important role in their cultural warfare efforts at home and abroad. The envelope of their cultural hegemony is such that any attempt to limit the circulation of their productions in any country is quickly assailed as unacceptable censorship, totalitarianism and Orwellian action. Meanwhile, in the U.S., foreign film products have, in most cases, such a limited circulation that they are effectively invisible, let alone receive appreciable screen time for foreign materials depicting the imperial face of its foreign policy.

It is not, moreover, the more obvious, the more dangerous the subtlety. In many cases, most of the time, it is not a diabolical conspiracy to cajole the public. It is enough that the cultural material is an organic part of the symbolic reproduction of the system where it is produced. If the scriptwriter, the producer, the director and the director are imbued with the conviction of the cultural superiority of their society, there is no need for an obvious hand to force it, the colonizing instrumentalization of the product will occur without Orwellian interventions.

The Cuban obsession in the spy saga is marked in at least three films from three different periods. In the most recent era of the franchise, which began with Pierce Brosnan, one of the installments shows us scenes in a tropical Cuba with spy installations of absurd sophistication. Crowning the ridiculousness is having the womanizing hero have a sex exchange scene in a cliché beach house, not under the protection of air conditioning, but the flames of a fireplace, a perfect recipe for a steamy heart attack.

To reaffirm the obsession, the recently released last installation of agent 007, which ends the segment of Daniel Craig, who must be credited with having given the character new life with his acting quality, almost at the beginning has its Cuban scenes, in this case supposedly from Santiago de Cuba. Designed from the usual commonplaces when it comes to reflecting Cuba in the canned products of commercial cinematography. Who knows if someday we will find out about cut scenes and twisting of arms to the script by the efficient censors, paladins of freedom of expression as long as it is not about them. Maybe not, after all, those confidentiality contracts can be very persuasive.

Leni Riefenstahl and a final adjustment

Leni Riefenstahl and a final adjustment

Filmmaker Nina Gladitz did not rest in tracking down what she called the sinister side of what was once called “the eye of Hitler”

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

The Riefenstahl, pampered by Hitler. Photo: Taken from the Internet

“The search for beauty in the image, above all and of all”, was the pretext used by the filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl every time she was reproached for having put her talent at the service of Nazism, and especially of Hitler, of whom she said in her memoirs (1987) that, after meeting him in a rally held in Berlin, 1932, “it was as if the earth opened up before me”.

Riefenstahl lived 101 years (1902-2003) and her actions have fueled a debate that involves art and ideology with the social and ethical responsibility of the artist.

Many did not forgive her fabricated naiveté to shake off a stigma that linked her to the crimes of Nazism, but there were those who extended a mantle of benevolence over her by arguing for the transcendence of her documentary, perfectionist and avant-garde work in German cinema.

Today, films such as The Triumph of the Will and Olympia are considered masterpieces of propaganda, based on a renovating formal aesthetic, taking into account the years in which they were conceived, and their capacity to transform reality into “ideological art”, if that is the concept for an ideology of extermination.

The first of these films turns the National Socialist [Nazi Party] Congress, held in Nuremberg in 1934, into an epic event of multitudes and leaders feverish with the word of a Hitler deified in images.

Olympia (1938) takes up again the fervor of the Führer for ancient Greece to link the 1936 Berlin Olympics with a symbolism of the Nazi racial myth, claiming that the proclaimed German civilization, superior in all respects, was the heir to an Aryan culture from classical antiquity.

“She is the only one of the stars who truly understands us”, Goebbels had said of the filmmaker in 1933, shortly after Hitler, a hardened film buff, signed her as the quintessential film diffuser of his party’s ideology.

The same Leni Riefenstahl, beautiful, willing, with a past that linked her to sports and snowy mountain climbing; also a dancer and actress who came to rival Greta Garbo in roles, was considered by Hitler an ideal of classic perfection. He put a lot of resources at her disposal and made her a pampered member of the group formed by the flower and cream of Berlin’s Nazism, who applauded her “neat and moving” style. And while there were those who spoke of a romance, she always denied it: “It wasn’t sexy, if it had been sexy, we would have naturally been lovers”. This did not prevent her from affirming, years later, that the triumph of Nazism had not been a political reaction, but the unusual adoration “of a unique leader”.

Riefenstahl managed to get Hitler to extend a high budget in 1940 to bring Tiefland (Lowland) to the screen, inspired by an opera (1903) by Eugen d’Albert that took place in Spain. The film would not be released until 1954 because, in addition to the author’s pedigree, there was something murky about it that had not been fully unraveled: Where had the gypsies from a concentration camp gone, since extras with a Mediterranean look were needed?

A murmur spread then: after the filming of Tiefland, those extras had been deported to Auschwitz.

Leni Riefenstahl, who after the war was investigated several times, subjected to four denazification processes, and finally exonerated under the ruling that she was only a “sympathizer” of the Nazis, protested against what she called slander and swore that she still had news, and even correspondence, with those gypsies.

In later years she would condemn the barbarism of which, she assured, she had witnessed nothing and used to reply to those who accused her: “my thing was art, to capture an era, a perception of ideology and not unrestricted support. Tell me, where is my fault, I did not throw atomic bombs, I have not denied anyone, where is my fault?”

In 1982, the gypsy nebula was brought to light in a television documentary by German filmmaker Nina Gladitz. The young filmmaker had located the descendants and they claimed that the director of Tiefland treated the extras like servants and then returned them to their origin, the Maxglan concentration camp in Austria, from where they were transferred, and killed, in the gas chamber of Auschwitz.

Leni complained to Gladitz, and although most of her allegations did not come to fruition, she came out saying that she had won the lawsuit. Her work had received by then a kind of rehabilitation, after the documentary Olympia had been shown, in 1972. When the filmmaker turned one hundred years old, she was, for many, more a legend admired for her technical and artistic contributions to cinema than a “circumstantial suspect” of having taken the symbols of Nazism to starry planes.

But the filmmaker Nina Gladitz did not rest in tracing what she called the sinister side of the woman who, at the time, had been called “the eye of Hitler”. A few days ago she published a book in which she exposes the complicity of Riefenstahl, and not only in “the artistic”. Documents show that 40 of the 53 gypsies were killed without the director doing anything to stop it, after having recruited them herself. Also, supported by archival materials, she reveals that the names of important collaborating filmmakers, such as Willy Zielke, who filmed the initial takes of Olympia (and ended up sterilized and mentally ill), were erased from her films, in addition to Leni interceding with Hitler’s top brass to prevent other filmmakers from filming; a behavior of which not a word had ever been said and in which she highlights -among other examples- the elimination of the credits, as co-director in Blue Light, of the Hungarian Béla Balázs.

According to Nina Gladitz’s book, the talented Willy Zielke was taken out of the asylum by Leni Riefenstahl with the aim of turning him into a prisoner-assistant. Shortly before the end of the war, she burned almost all the files she owned in the gardens of her villa. Judging by classified French intelligence materials reviewed by Gladitz, that fire included scenes of the destruction of a Jewish ghetto shot on Hitler’s orders, although no one knows if the film ever materialized.

A definitive adjustment then for the filmmaker who ran to film the Nazi invasion of Poland, where she was photographed in uniform, together with German soldiers and carrying a gun around her waist, and for whom, after the occupation of Paris, she wrote the following telegram to Hitler: “With indescribable joy, deeply moved and full of ardent gratitude, we share with you, my Führer, your greatest victory and that of Germany, the entry of German troops into Paris. You surpass all that the human imagination has the power to conceive, achieving facts without parallel in the history of humanity. How can we ever thank you? Congratulating you is too little to express the feelings that move me.”

How was that cable possible, Leni Riefenstahl was once asked, and she, with the unheard of “naivety” that some people still use at times to alternate with their inexplicable ravings, replied: “Everyone thought the war was over, and in that spirit, I sent the cable.”

Restored “Last Supper” at Venice

Restored The Last Supper at Venice Film Festival

The digital restoration of The Last Supper, made by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea in 1976, will be screened as part of the Classics section at the 77th Venice International Film Festival, which will take place between September 2 and 12 next

By Joel del Río

digital@juventudrebelde.cu

August 22, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

I would like to explain that the title of this work has nothing to do with Leonardo Da Vinci’s famous fresco, nor is it related to any gloomy prediction for the Italian city also called La Serenissima. I am referring rather to a transcendent Cuban film, which has fortunately been restored, and will be exhibited with honors at the next Venice International Film Festival.

This year’s event, because of the physical distance, a very limited public of critics and a few foreign guests will attend. Meanwhile, this and other competitions, such as the one in Toronto, value the exhibition of the films through websites with streaming services, to be downloaded only by the people authorized to view them.

The digital restoration of The Last Supper, made by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea in 1976, will be screened as part of the Classics section in the 77th edition of the Venetian event, which will take place between September 2 and 12. The copy will have its world premiere at the Il Cinema Ritrovato (The Rediscovered Cinema) Festival in Bologna, which will take place from August 25th to 31st, and will also be added to the list of restored classics offered by Venice, under a collaboration agreement.

In the 34th edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato, not only the aforementioned work by Titón will be shown, but also two of his other films. All three have been restored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences of Los Angeles, USA, in collaboration with the Cuban Cinematheque: the short documentary El arte del tabaco (1974) and the feature film La muerte de un burócrata (1966), which was at the Mostra last year.

It is never pointless to reflect again on the merits of Cuban art, even when it is taken as a pretext at this moment in which two classic films attract the attention of the most prestigious film events and institutions in the world. It should be noted that both productions were prophets in their own land, and placed, in their own time, in the deserved places, thanks to the attention of the public and the critics.

The death of a bureaucrat was constructed as a buzzing mockery of the unbearable “traversed” in the normal development of society. It attacks the plague of schematic and inflexible officials that build the despair of the central character, and highlights the tragic chaos around a simple and essential procedure.

Considered one of the most eloquent cinematographic satires on the administrative inadequacies of any society, the film inaugurates critical realism with absurd and unreal touches that allowed the national cinematography to elude the narrow representational frameworks, sometimes imitative, of Italian neo-realism.

For its part, The Last Supper was first seen on November 3, 1977 in the Yara, Acapulco, Metropolitan, Monaco, Florida and City Hall theaters (how wonderful to have so many theaters on the premiere circuit). Among its many international awards are the Golden Hugo of the International Film Festival of Chicago, the Grand Prix at the Biarritz Ibero-American Film Festival, the Golden Columbus in Huelva, the distinction as outstanding film at the London Festival, best foreign film exhibited in Venezuela, Grand Prize at the Figueira Festival in Foz, Portugal; and winner of the Popular Jury in the II Muestra Internacional de Cine Sao Pablo.

Ten years after making the brilliant contemporary satire on the problems of bureaucracy in Cuba, Gutiérrez Alea made a foray into historical production with his first color film, La última cena (The Last Supper), inspired by an anecdote about a real event that appears in the book El ingenio (The Sugar Mill) by Manuel Moreno Fraginals.

He wrote an extensive and medullar study of the plantation economy in the era of slavery in Cuba. While the action took place at the end of the 18th century in a sugar mill, the advice given by the historian to the filmmaker was very important. He also had the help of the knowledge of specialists such as Rogelio Martínez Furé and Nitza Villapol, because it also told the story of a rich count, very religious, who gathers 12 slaves and invites them to dinner, in the way of a similar invitation narrated in the Bible.

During dinner, which takes up most of the footage, the count talks to his servants and tries to explain to them the principles of humility and resignation that guide the Catholic religion. The slaves, convinced of their goodwill, decide not to work the next day and thus a repression is unleashed with tragic consequences.

It is a temporary analysis of power and dependence, because, as the director stated to Gerardo Chijona in the interview published in the magazine Cine Cubano number 93: “…a historical film, for me, is not to reconstruct in a spectacular way the fact itself. I’m not interested in archaeological work, but rather in taking advantage of history at some point because of the repercussions that this can have on the present.

Editor Nelson Rodríguez told the Cubasí website: “The filming of the dinner sequence was a real challenge in terms of staging, it lasted about four weeks and was shot continuously, that is, in order, almost in real-time. It was really a challenge, because the continuity demanded special care in all the elements, from the care with the candles, the food, the wines and of course the work of the actors. The edition was a real feast, because there was not the slightest error in the setting or in the continuity”.

In this respect, it is worth adding that in the famous long sequence the director films the table from the front, with the count in the middle, and resorts to a backward movement, and then a forward movement in the camera, as if to emphasize the theatrical air of the representation and the pictorial reference in Da Vinci’s painting.

It is unlikely that the director attempted a diatribe against Catholic ideology. Rather, I believe that he intended to question, indirectly, all the usual manipulations of the powerful, with respect to a certain idealistic and egalitarian rhetoric. His goal was to confirm in the background the predominance of the ruling class over a group that he considers inferior and anonymous.

So when the count refers to the acceptance of sacrifice and suffering, he never thinks of adopting that philosophy himself, but of having it endorsed by the slaves, forced to assent to their subordinate condition. This and other reflections come from one of the most brilliant and intelligent films ever made in Cuba. Now it can be enjoyed again in a good copy.

Since I am not invaded by the diagonal chauvinism of reporting on an event as enormous as the Venice International Film Festival only from the perspective of Cuban participation, we would at least like to point out that in the official section, where the premieres of the great filmmakers compete, among others, the Japanese master of horror Kiyoshi Kurosawa (The Spy’s Woman), the new revelation of Polish auteur cinema, Malgorzata Szumowska (It Will Never Snow Again), the world’s most acclaimed Israeli filmmaker, Amos Gitai (Laila in Haifa), the several times acclaimed Russian director Andrei Konchalovsky (Dear Friends), and the Iranian master of neo-realistic melodrama starring children, Majid Majidi (Children of the Sun).

In short, Cuban cinema continues to occupy prestigious spheres, because beyond the honors given to two essential classics. Itt was also announced a few days ago that the independent production Agosto, directed by debutant Armando Capó, will represent us in the 24th edition of the Lima Film Festival, which this year will also have an online version, due to the coronavirus, from the 21st to the 30th of this month.

In the same event, the documentary A media voz, co-directed by Heidi Hassán and Patricia Pérez, will be shown via internet throughout Peru, and will finally be released in Spain as part of the official selection of the Malaga Festival, on August 23rd in the Echegaray Theater.

Both Agosto and A Media Voz have gone through a long list of important international contests, and both were awarded with top choirs in their respective categories (debut opera and documentary) at the most recent Festival de La Habana. Cuban cinema does not live by past glories alone.

I’m Not Who You Think

spectator’s chronicle

I’m Not Who You Think

By Rolando Pérez Betancourt

By Rolando Pérez Betancourt

July 12, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

After 35 years of sustained triumphs in various films, French actress Juliette Binoche is once again shining in her latest film, which will soon be shown on Cubavisión.

I’m Not Who You Think (Safy Nebbou, 2019) is the story of a divorced, 50-year-old literature professor with two children who uses the tricks of Facebook to create a profile that turns her into an attractive 24-year-old blonde.

The causes and consequences of this change will be the main theme of this romantic drama with a thriller-like twist. It’s conceived in the midst of human relationships conditioned by technology and the masks that encourage so-called catfishing, or [creating a] non-existent identity in social networks with the aim of attracting unwary people.

In days of unbridled love passions on Facebook, Twitter and Whatsapp, director Safy Nebbou waves the trump card of Binoche and squeezes it into the role of a middle-aged woman trapped in the obsession of feeling wanted. Why not fall in love with a young man much younger than she? And the protagonist embarks on the adventure, even if she ends up in the hands of a psychiatrist. This is a resource that is used from the beginning to weave the threads of the story in two stages and thus expose the intimate worlds of a woman who, after the divorce, was exposed to the risks of depression.

The film takes a critical look at the lies and manipulations of social networks and is a treat for viewers to reflect on issues such as the fear of growing old, the age difference when it comes to love, and whether it “looks good” for a mature woman to go crazy with love (and delude herself into madness), as she would have done in her twenties.

We will then see an exceptional Juliette Binoche fall silent, when a young lover tells her that she could well be her mother; chat in the solitude of her home, pretending to be the little girl she is not; fall into the chaos of uncertainty and moral collapse; shine like a sun and explode into childish euphoria when she feels wanted.

The film is all of her, and also a story of loneliness on days when it seems that everyone is connected.

Viola Davis Regrets Acting in THE HELP

Viola Davis Once Again Regrets Performing in THE HELP

July 15, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Viola Davis plays Aibileen Clark in the 2011 Maids and Ladies Firm. Autor: Frame of the film Published: 07/15/2020 | 02:50 p

This is not the first time that Viola Davis has publicly rejected her role as Aibileen Clark in the drama THE HELP, which this time she has described, in an interview with Vanity Fair magazine, as a film that maintains “the narrative of the white savior” and that did not give enough prominence to the black maids, reports the DPA agency.

The actress, who was nominated for an Oscar for best lead actor for her appearance in that film in 2012, has once again shown her regret, now within the context of the Black Lives Matter movement. Already in 2018, Davis showed h displeasure with the film directed by Tate Taylor in 2011.

“There’s no one who hasn’t enjoyed THE HELP, but there’s a part of me that feels I betrayed myself and my people,” Davis explains in an interview for the magazine she’s the cover of. “I was in a movie that wasn’t programmed [to tell the whole truth],” she adds, denouncing that the film is made “with the filter and the sewers of systematic racism.

Davis also denounces the lack of Black voices in the creative process in Hollywood. “There are not a lot of narratives that are involved in our humanity [referring to the African-American community],” she explains. She adds that the writers, directors and producers “try to delve into the idea of what it means to be Black, but thinking essentially about a white audience.

She added that in Hollywood “there are not enough opportunities for an unknown Black actress” to “get ahead” in the industry. In this way, Davis, who had already been nominated for an Oscar before THE HELP for her role in THE DOUBT, justifies her participation in the film that also starred Emma Stone, Jessica Chastain, Bryce Dallas Howard and Octavia Spencer, who won the Oscar for this film. “I was that actress who was trying to get into [the industry],” she says.

Not only Viola

Just a few weeks ago, Bryce Dallas Howard also disowned the film and recommended that the public not see THE HELP as a reference for fighting racism. The singer also added that she “would not” have participated in the film if it had been shot today.

It was in an interview with the Los Angeles Times that the Jurassic World actress spoke about the need to give voice to Black creators and for them to be the ones to address the African-American reality.

“I wouldn’t appear in the film again [if it had been made today]. I’ll tell you why: I’ve realized that now people have the courage to say, ‘With all due respect, I love this project, but I don’t think you should be the one to direct it. That’s a very powerful thing, to be able to say it,” the actress explained.

“In this transformation that’s happening, a new freedom of expression is emerging,” Howard added, emphasizing the importance of black voices in the industry, referring to the Black Lives Matter movement.

The Wasp Network

The Wasp Network and the Never-Ending Claque

by Rolando Pérez Betancourt

by Rolando Pérez Betancourt

July 4, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

The controversy and the pandemic have meant that The Wasp Network continues to be seen far beyond what the most flattering estimates had predicted.

This is despite the fact that some involved in the film plot have vowed to ignore it and continue to call for a boycott, while demanding legal redress “for damages”.

But they betray themselves and, in the loneliness of their homes, sit in front of the Netflix platform, eager to know. Afterwards, they can’t stop themselves and they explode, even though the shouting is evidence of having broken a pact with the Brothers, as happened to Ramón Saúl Sánchez, an old sidekick of the terrorist Posada Carriles and a counter-revolutionary linked to those first groups determined to return Cuba to what it was before 1959.

Sanchez is offended because the film “is more a political project than a cinematographic story”, a statement that invites one to imagine a science fiction plot, with the French director Olivier Assayas, the producers from different countries, technicians, actors, and Netflix itself, involved in an international conspiracy

interested in advocating Cuba’s right to defend itself against the terrorists in Florida, who are being suckled by the United States Government.

What really bothers the explosives expert of the Omega-7 terrorist group is that the film presents him as one of the many who have made counterrevolution a lucrative business, and it is true that many of his lineage are trying to shake off the image of the “patriot” swimming in ugly money that does not dignify the cause.

That’s why the also member of the Alpha 66 group (with a bloody record of service against the Cuban people) is indignant about the uncomfortable position in which the film places him and he claims, with an air of offense, that the money that came out of his pockets to unite the Cuban family was not a small thing. A statement after which -according to statements published on the Internet- he explains what a lavish money-maker he is: “I even had to pay a bill for 800 dollars in calls to Cuba once”.

A reminder of the “who’s who” of the adventure of moving around social networks by watching the reactions to The Wasp Network. This is how Carlos Alberto Montaner emerged, an old terrorist and agent of the cia (with an evidentiary record) who had become a “political analyst” without ceasing to be an ardent counter-revolutionary. He was another one of those who, “without wanting to”, watched The Wasp Network, because – in keeping with the ideals of the high-ranking intellectual who questions everything – he could not believe the argument that the tape “was pure propaganda paid for by Havana”. In other words, supposedly devoid of prejudices and ideological positions, the analyst saw the film, after which he considers it a mistake, because, in effect, “it is propaganda paid for by Havana,” a risky slander – he should have known – since he too could be sued by the film’s producers and, on this occasion, not without reasons to open a court case.

Once again, cinema and art, in their historical implications, are blinded by extreme positions that prefer bonfires to analysis. Hatreds, swearwords, disqualifications, emptiness, savagery of the verb, unhealthy propaganda against those who simply give a frank opinion, as happened to the Spanish vice-president, Pablo Iglesias. “Sight. Heroes. Movie”, wrote the leader with total frankness, and the furious claque, which is never absent, waved torches and went out to set fire to the nets.

A World Without Movie Screens

A World Without Movie Screens

by Julio Martinez Molina

by Julio Martinez Molina

Audiovisual critic and journalist, member of the Cuban Association of the Film Press and UNEAC. Author of the books published on film criticism in North America and the end of the century, Causes and Influences of Contemporary Cinema and Haikus of My Filmic Emotion. From his blog, La Viña de los Lumiere

March 16, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

Whether or not it is a bacteriological weapon of the United States aimed at slowing down China’s advance, the coronavirus has seriously affected the world economy; especially that of Washington’s main rival, yes, but its overall effects reach a planetary scale, including the northern nation itself.

Whether or not it is a bacteriological weapon of the United States aimed at slowing down China’s advance, the coronavirus has seriously affected the world economy; especially that of Washington’s main rival, yes, but its overall effects reach a planetary scale, including the northern nation itself.

The saddest images of the harshest dystopias are now verified, not in book pages but in real scenarios characterized by desolation. What happened or is happening in nations such as China, Iran, Italy and Spain surpasses any science fiction or fantasy narrative.

A world on edge sees closed borders, has confined millions of citizens, separated regions and blocked the entry of tens of thousands of people.

This attack on humanity does not understand geography, economic classes, or climate. Nor of fields, sectors, industrial universes and the entertainment industry. The latter is experiencing a very strong contraction at a global level, except in streaming giants such as the American platform Netflix or in the pornography industry, an emporium that annually moves more money in the US than the NBA. The same coronavirus has even been a callous theme in several “adult films”.

Now, beyond such exceptions or others very pointed, the turn suffers the biggest cliff in its history. The plunge in ticket sales meant a 45 percent drop this weekend in the U.S. and Canada. In the main cities of both nations, theaters were closed during the night of Sunday the 15th. The start of the closures was marked by China on February 2, when the Alliance of Radio, Film and Television Production Committee and the Federation of Radio and Television Association directed film companies, production teams, actors and actresses to cease work.

Both there and in the US, India (the country that produces the most films per year in the world), France, Spain and Italy paralyzed film activity. The Los Angeles Times reports that “the Fast & Furious franchise has decided to postpone the release of its ninth film for a full year. Neither will the new James Bond film, No Time To Die, a decision made several weeks ago to postpone the release from April to October. For its part, the Disney giant’s coronavirus agenda could not have been worse: Its big bet for spring was the new version of Mulan, a film that, for obvious reasons, has the Asian market as its main focus.

“After postponing Mulan’s global release and closing its theme parks, Disney has taken another drastic decision to curb the coronavirus: to suspend production of all its films, with animation as an exception. This way, the new version with real actors of The Little Mermaid will delay its shooting, which was going to start soon in London, as well as William of the Bull’s thriller Nightmare Alley, Ridley Scott’s drama The Last Duel and the next installment of Home Alone. The new Peter Pan and Wendy, as well as Shrunk, a sequel to the 1980s classic Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, were also delayed, although both were in early pre-production.

“Disney’s decision affects a large number of studios the company owns, such as Fox and Searchlight. Marvel, also under its control, suspended the filming of Shang-Chi and The Legend of the Ten Rings, after its director, Destin Daniel Cretton, has been isolated by his own decision. The Mickey Mouse factory has also suspended some 16 television pilots for the same reasons. They have also interrupted filming in other different studios such as Mission: Impossible in Italy, Official Competition – with Penelope Cruz and Antonio Banderas – in Spain, and The Amazing Race” competition around the world. And preparations for filming the biography of Elvis Presley have been slowed down after one of his protagonists, Tom Hanks, tested positive for the coronavirus in Australia,” says the half-Angelian.

Shooting on Sony’s Budapest-based The Nightingale, starring sisters Elle and Dakota Fanning directed by France’s Melánie Laurent, also stopped. The Malaga (Spain) and Guadalajara (Mexico) film festivals were cancelled. And so, unstoppable is the rosary of news that arrives every morning.

It has been published that the losses may frustrate the five billion dollars, a peak that I consider extremely low given the circumstances.

Movies and the Coronavirus

Movies and the Coronavirus

By Rolando Pérez Betancourt

March 16, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

A few days ago, actress Gwyneth Paltrow appeared on social networks wearing a mask and this recommendation: “I’ve already been in this movie. Stay safe. Don’t wave. Wash your hands often.”

The film Paltrow was referring to is Contagion (Steven Soderberg, 2011), the most-watched on the Internet in recent weeks because of its similarity to that global scourge that keeps humanity against the wall, Covid-19.

Contagioun has a first-rate international cast: Jude Law, Marion Cotillard, Kate Winslet and Matt Damon, in addition to Paltrow, and is the film, within the genre of catastrophe, that most resembles what we’re experiencing, something like if since fiction its scriptwriter, Scott Z. Burns, had been sending out a warning message.

Gwyneth Paltrow has posted an image on Instagram recalling the film Photo: Instagram

In Contagion, Soderberg once again demonstrates his ability to combine experimental films with documentary elements and commercial touches, a formula that, through the use of breathless editing, opens the doors to vast audiences, while at the same time immersing the viewer in an atmosphere of tribulation.

The film talks about a virus that is supposedly transmitted from Hong Kong. Gwyneth Paltrow’s character, infected by a chef who shakes her hand after preparing a strange dish, later visits a casino where she blows the dice on a man who will die two days later. There he will contaminate everyone who approaches him, people who in a few hours will take planes to different parts of the world. On her way back to her native Minnesota, she falls ill and dies.

The epidemic takes on a global dimension and scientists begin to work on a vaccine, while the most diverse reactions take place in a film that gives great importance to the secondary characters: a blogger who denounces an international conspiracy that links the government with the pharmaceutical industry, cases of extreme selfishness, countries with no economic possibilities that are not involved in international cooperation, the manipulative role of the media and the lukewarmness, at the level of the nation and from the first moments, with which it faces what is happening.

Soderberg once again demonstrates in Contagio the ability to combine his experimental cinema with documentary elements and commercial touches Photo: sensacine.com

It is true that there are other films that deal with the subject, but none with the realism of Contagioun, hence the worldwide resurrection that makes many people look for it, and especially those people who remain in quarantine in their respective countries, perhaps because after long anguished suspense of anguish, the conflict opens the way to hope.

It is logical that in this “re-envisioning” the scriptwriter of Contagion, Scott Z. Burns, a faithful collaborator of Soderberg, returns to the foreground – with greater force than nine years ago. Interviewed by the website Slate, he had no qualms about condemning the cold actions of some governments in the face of the pandemic, starting with President Trump, who in the first moments relied more on his elusive messages via Twitter than on concrete actions.

According to Burns, while writing the script for the film, he went to meet with leading scientists who told him that the issue was not whether what he said could happen, but “when” it would happen. “When scientists say something, it’s better to listen,” the screenwriter said, and he had words of praise for the professionals at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control who advised him on his script. But he complained, “We’re finding out that we don’t have enough kits to test and for some reason, we’ve dissolved our pandemic response teams.

Speaking of the many people who tell him that the film was becoming a reality, Burns responds that he said, “I never imagined that there were leaders in this country who would leave us defenseless.

From a long interview appeared on the Slate website and an extensive lunge by Scott Z. Burns: “The administration and the Republican Party talk about protecting people with a wall [on the border with Mexico], but we don’t even have test kits. And he blames the lack of measures against hoarding, demonic price hikes, and other reprehensible aspects. “Where is the law when there are people on the Internet selling miracle cures?” he wonders. Those who saw the film remember the tricks of a grotesque con man in it, one more similarity of the many that come to show that, between fiction and reality, only the passage of life is in between.

Parasites, Trump and Gone with the Wind

Parasites, Trump and Gone with the Wind

Viewers who’ve seen Parasites, and know of its quality, still scoff at the critical mess cooked up in Colorado, especially after the film’s producers responded that the problem is that the president can’t read subtitles. But what did Trump mean when he said “let’s bring back Gone With the Wind”?

by Rolando Pérez Betancourt | internet@granma.cu

February 25, 2020 22:02:03

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Gone With The Wind frame. Photo: Film frame

No one is forced to applaud a film praised by half the world, but at least, before giving an opinion, you should see it.

In his harsh criticism of the Oscar-winning film Parasites, President Trump let it be known that it was unknown, which did not prevent him from accusing it of being foreign, because it speaks another language, has subtitles, its protagonists are Asian, and – this last must have been blown by any advisor on the return from the cinema – it is a political and social allegation against the system that he reveres!

The film world already knows that anyone who tries to challenge the president’s actions will be diminished by insulting Twitter messages. Thus, Meryl Streep is “a second-rate actress,” Robert de Niro “a very low IQ individual,” Black director Spike Lee “a racist,” actor Alec Baldwin (who mimics him on Saturday Night Live) a conspirator “who should be punished along with the show,”. This recently led Baldwin to compare him to Hitler, and the latest pearl of the show, from a few days ago, during the election meeting in Colorado, where he criticized Brad Pitt – “I was never a big fan of him; he stood up and said a smart thing, he’s a smart guy”- because the actor, after receiving his Oscar, joked about the political process, without witnesses, who “judged” Trump.

The flag-waving minions of the Republican Party cheered when the president, on the campaign, was bewildered by Parasites’ Oscar, and called for a return to the days of awarding films like Gone with the Wind. This was a warning from the top of the establishment to the winds of change that – for the sake of maintaining hegemony and other considerations – seem to be coming to the Hollywood Academy: “… a

South Korean movie! What was that about? We have enough commercial problems with South Korea already. On top of that, we’re giving them the Best Film of the Year… Was it good? I don’t know. Let’s bring back Gone With the Wind, please. Twilight of the Gods. So many great movies…

Viewers who’ve seen Gone With the Wind, and know of its quality, still mock the critical mess cooked up in Colorado, especially after the film’s producers responded that the problem is that the president can’t read subtitles, but what did Trump mean by “let’s bring back Gone With the Wind?”

First-hand conservatism and racism, no more and no less, and along with it, offensive misinformation, unless, knowing the terrain he was treading on, he didn’t care about restoring the laurels of an anthological film, yes, but in the background of evaluations after it was established that, in addition to its racist overtones, it didn’t lack syrups and other tricks to idealize the slave-owning past of the South.

In the middle of the 21st century, the myth of Gone with the Wind, elevated to the empyrean by the enormous marketing that accompanied it, slips and cannot be sustained. A little over two months ago, on December 15, 2019, it was 80 years since its massive premiere in Atlanta. However, Hollywood preferred to go overboard and exalt instead The Wizard of Oz, also from 1939.

In the documentary The Legend Goes On (2014), the prestigious American sociologist Camille Paglia situates in a simple way what the film was: “it is not honest with what the slaves of that time felt”.

In August 2017, the Orpheum Theatre, a historic movie theater in Memphis, decided to withdraw its annual exhibition of Gone with the Wind after the bloody racial clashes that took place in Charlottesville (Virginia), where it became clear that race relations are still a pending issue in the United States. Trump received harsh criticism for his verbal lukewarmness towards white supremacists, a sector encouraged by the Republican boom: “It’s both groups’ fault,” Trump said in those days, washing his hands of where the attacks had come from, like the neo-Nazi who killed a woman with his car.

While there is no shortage of Gone with the Wind advocates as material from which critical lessons can be drawn. It’s all very well for it to be seen as an epoch-making cinema classic, but its racist weight is too strong for the new, non-conservative generations to take into account. This, without losing sight of the fact that, as a commercial film, the film crowned the Hollywood of spectacular sound and color alongside the proclaimed star system.

The all-powerful producer [David] O. Selznick is known to have emptied Margaret Mitchell’s romance novel of anything that might be critical of Southern racists. These inluded references to the Ku Klux Klan founded by America’s far-right in 1865 with veterans of the Civil War. But it is enough to see how the liberated blacks, potential criminals, are represented to be intoxicated by the racist stench that emerges from the film.

The Hollywood Academy tried to mitigate the issue by giving Hattie MacDaniel the secondary Oscar, the first black actress to receive it, for her good performance as Scarlett O’Hara’s “Mamie”. The horror came later, when, at the awards ceremony, for being black, and also a lesbian, she was seated on a separate bench, far away from her fellow filmmakers, and then she was not allowed to attend the banquet of the winners because the segregationist laws did not allow it.

Bringing back Gone With the Wind films to face films like Parasites?

No way to think of a respectful response.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

You must be logged in to post a comment.