Racism 18

Esteban Morales Domínguez has passed away

Renowned intellectual Esteban Morales Domínguez has passed away. (+ Video)

A member of the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba and of the José Antonio Aponte Commission, in which he developed an intense work, he bequeathed an important series of essays in the field of the study of the links between Cuba and the United States.

Autor: Pedro de la Hoz | pedro@granma.cu

May 18, 2022 19:05:15 PM

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

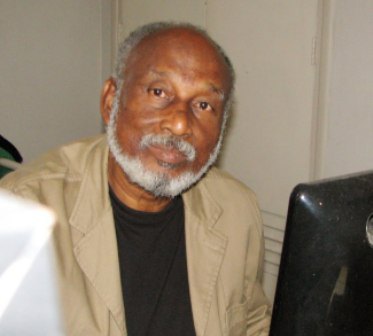

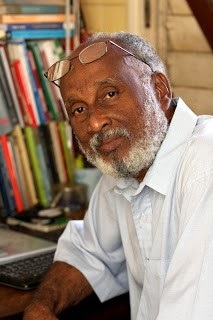

Esteban Morales Photo: Cubadebate

Renowned essayist, political scientist and professor Esteban Morales Domínguez died Wednesday at the age of 79, victim of a heart attack.

Through Twitter, the First Secretary of the Party Central Committee and President of the Republic, Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez, wrote about the intellectual:

“The surprise death of Esteban Morales pains us. We will miss his intelligent, incisive and committed assessment of the problems of our time. My condolences to his family, friends and the Cuban intelligentsia, which he gave prestige to with his work”.

A member of the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC) and of the José Antonio Aponte Commission, in whose bosom he developed an intense work, he bequeathed important written work in the field of the study of the links between Cuba and the United States.

Among the most significant titles in this field are Cuba-United States Relations: A Critical History and From Confrontation to Attempts at Normalization: U.S. Policy Toward Cuba, the latter in collaboration with essayist Elier Ramirez.

In another sphere, one of his books of greatest impact was Desafíos de la problemática racial en Cuba, published in 2007 by the Fernando Ortiz Foundation.

Morales’ intellectual career was linked to the University of Havana, where he was initially trained as an economist, devoted himself to teaching, and served as dean of the Faculty of Humanities and founding director of the Center for Studies on the United States.

Díaz-Canel on racism at the UN

Díaz-Canel at the UN: The peoples of the world will always be able to count on Cuba’s contribution (+Video)

Speech by Miguel Díaz-Canel, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Cuba and President of the Republic, at the High-Level Meeting during the General Debate of the 76th Regular Session of the United Nations General Assembly

Author: Redacción Digital | internet@granma.cu

September 22, 2021 10:09:29 am

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Photo: Estudios Revolución

(Shorthand Versions – Presidency of the Republic)

Mr. Secretary General;

Mr. President:

The world should be ashamed to observe the poor scope of universal agreements that were once the hope of the excluded and the dispossessed.

Twenty years after the adoption of the Durban Declaration and Program of Action, the objectives set out in those documents for the fight against all forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance have not been achieved.

Structural racism persists. Hate speech, intolerance, xenophobia and discrimination proliferate at worrying levels, including on social media and other communication platforms.

Developed capitalist countries try with demagogic speeches to divert attention from their historical responsibility in the enthronement and persistence of these scourges and their debt to the peoples who are victims of the slavery to which they were subjected. There is a lack of political will on the part of these same countries to make the promises of the Durban Declaration and Program of Action a reality.

The multidimensional crisis generated by the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the structural inequalities and exclusion inherent to the prevailing unjust economic order, which subjects the poor, those of African descent or migrants to all kinds of discrimination.

Mr. President:

In Cuba, beyond skin color, African, European and Native American genes are all mixed . We are one people, Afro-Latin, Caribbean, mestizo, in which several roots were fused to forge a unique, vigorous trunk, with its own identity, open to the world from a sense of belonging in which cultural values are assumed from an ethic of solidarity.

With a colonial slave-owning past, the black and mulatto Cuban population suffered for centuries the consequences of a system in which racism and racial discrimination were part of everyday life. Only with the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959 did a process of radical transformations take place that demolished the structural bases of racism and eliminated institutionalized racial discrimination forever.

The advocacy of hatred, the promotion of intolerance and supremacist ideas on the basis of national, religious or ethnic origin and xenophobia are alien to the political, social and economic life of the country.

The new Constitution of the Republic of Cuba ratified and strengthened the recognition and protection of the right to equality, as well as the prohibition of discrimination.

The Magna Carta provides that all persons are equal before the law, receive the same protection and treatment from the authorities and enjoy the same rights, freedoms and opportunities; but laws and decrees are not enough to erase centuries of discriminatory practices in societies.

To make further progress in the emancipating work of the Revolution, the National Plan against Racism and Racial Discrimination was approved in November 2019, as a government program that favors the most effective confrontation of racial prejudice and social problems that still exist in our society.

Cuba’s commitment to the eradication of racism transcends its borders. Thousands of Cubans supported national liberation movements in Africa and against the opprobrious apartheid regime. Thousands of others have contributed their solidarity aid, particularly in the area of health.

We will not relent in our pursuit of social justice. The peoples of the world will always be able to count on Cuba’s contribution so that the commitments we assumed 20 years ago in Durban become a reality.

Thank you very much.

[1] The Cuban Genetic Map, 2015 Cuban Academy of Sciences Award, indicated that on average, without distinction by skin color, genetic crossbreeding marked the presence of European ancestral genes in a proportion of 73.8%, 16.8% of African origin and 9.4% of genes of Native American origin.

#UNGA76 Aniversario 20 Declaración del Programa de Durban | Participará el Presidente @DiazCanelB a partir de las 11:00 am de hoy. El Sitio de la Presidencia se unirá a la transmisión junto a sus canales en:

➡️YouTube

➡️PICTA#EliminaElBloqueo #Cuba🇨🇺 pic.twitter.com/J2g8OM5srD— Presidencia Cuba (@PresidenciaCuba) September 22, 2021

The Census, Skin Color and Social Analysis

- English

- Español

The Census, Skin Color and Social Analysis

Esteban Morales

by Esteban Morales Domínguez

Translated by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

June 30, 2021

Although it still causes many prejudices, misunderstandings and challenges, there is no choice but to pay attention to skin color. Above all, in its consideration within the media and national statistics.

Cuban society is a multiracial society, or rather, multicolored, mestizo. And that reality has to be registered statistically. Not by handling the Census as a simply numerical matter, but as a cultural demographic one.

It is about the fact that color is a legacy of slavery. It is not possible to avoid it, since it has marked Cuban society since its origins.

When the Spaniards arrived in Cuba, in 1492, they did it with white credentials and that is how they stayed. Those who came of their own free will did so in search of a fortune, which they often found.

But Spain is not White. Colonized by the Arabs for 800 years, it is impossible to consider it as such. Even when the Spanish do not assume that identity.

So, the colonizers of our Archipelago were not white. Their power did not consist in being white, but in having arrived with the cross and the sword.

They arrived in a territory of indigenous people, of low culture and they only used them to find gold. They exploited them mercilessly and their population mass did not last long, although we still have representatives of that original population in Cuba.

Chinese also came, brought by means of a system of contracts that turned them into slaves. The so-called “culíes” [coolies], who since then added their beauty to the population of the Island, becoming a part of our nationality. These three large groups were the ones that formed the Cuban population. Later, other Antilleans joined, although not in the magnitude of the first ones, also merging with our population.

Although the Spanish Crown, put rules for the care of the indigenous population; anyway, the ambition of the colonizers, together with the regime of the Encomiendas and slavery, reduced that population to its minimum expression.

In little more than 100 years, the so-called Tainos, Siboneys and Guanahatebeys, almost disappeared, because they were not of an advanced culture, as it happened for the rest of America. Cultures, Aztecs, Mayas, Toltecs, etc. Those that did, culturally, had practically nothing to envy to the European cultures of their time.

But the existing indigenous population in the Cuban Archipelago lacked the strength that comes from belonging to a superior culture.

Along with the Spaniards came the first blacks. Not from Africa, but directly from Spain. Those blacks were called “Ladinos”. They were slaves in Spain. They knew how to speak the language and had a certain culture, acquired in the work of servitude, for which they also arrived in Cuba. But they did so in reduced numbers.

The vast majority of the blacks who arrived in Cuba, massively, did so later, as a result of the slave trade. And massively, after the Haitian Revolution of 1791, they settled in the eastern end of the island. They had a great cultural impact, since they were accompanied by their French masters. This is how the French contradanza and the so-called Tumba Francesa arrived in Cuba. All of which, we know as antecedents of our national dances, the Danzón.

Through the eastern region, the Antillean groups entered to participate in the sugar production, hence the mixture that characterizes that region, which covers up to the current province of Camagüey, where we find many descendants of French (Haitians), or English (Jamaicans) and other Antillean groups. This made the situation of racial discrimination in the aforementioned regions more complicated.

However, they did not give rise to the formation of minorities, as in the United States, but merged with the Cuban population, keeping their English and French surnames.

Then, the blacks were brought as slaves to Cuba, first for the work of construction and later for the work of sugar production, within a colonial regime already organized. To say black in Cuba was to say slave.

These slaves, practically, since the XVI century, could buy their freedom.

As the Spaniards arrived, they were men alone. Immediately, they began to mix with the Indians and blacks, thus initiating the mestizaje of the Island. And within a complex mestizaje, because it was formed by free or enslaved people, mestizos or blacks. Not so the Spanish whites, who never suffered the condition of slavery.

Unlike the blacks who were brought to the territory of the Thirteen North American colonies, which later became the United States of America; those who arrived, also brought from Africa as slaves to the aforementioned territory, could not speak their languages, but only English, they could not practice their religions or their cultures. They were not allowed by the colonizers. In this sense, the slave regime coming from England was harsher, with an almost absolute separation between blacks and whites. That is what has ended up characterizing the American society.

To blacks brought to Cuba, also from Africa, the Spanish colonization allowed them to speak their languages, worship their gods and practice their cultures.

It was that, for historical and cultural reasons, the Spanish were more inclined to coexist with the cultural practices of the slaves in Cuba and with the different colors.

Unlike in North America, in Cuba, the Spaniards coexisted better with the differences in color. This also contributed to the differences introduced in black slavery by the existence of domestic slavery and plantation slavery.

In Cuba this did not take place, but in the American colonization, there was a type of colonizer who, not having money to cover the expenses of his transfer to America, requested a loan, which obliged him to work, practically as a slave or serf. Once the loan debt was paid, he received a piece of land, becoming a poor farmer. Except for the existence of some slaves, who did not live in the barracks and cultivated a small piece of land, to supply the master’s house, in Cuba there were never serfs as such.

On the plantation, blacks had to work from sunrise to sunset, under the whip of the Foreman or Overseer. Meanwhile, in domestic work, the tasks were deployed in the house of the slave owner, intertwined with the activities of service to the family. There one could be a coachman, cook, seamstress, wash and iron, set the table, mend the master’s clothes and made him a concoction, when he was ill, etc. Performing tasks that practically prepared him for a trade, in case one day he was able to obtain his freedom, bought or manumitted.

The contact with the family instructed them and endowed them with a certain culture, which differentiated them from the plantation slaves. They were only allowed to work in sugar cane cutting or sugar production.

Blacks, wherever they were, were still slaves, and the trap, before the slightest disobedience, was over him, like the Sword of Damocles. For the white master did not allow them those freedoms that could inculcate in them a culture of independence, which was closely guarded. But, in domestic work, in fact, the advantages, they had them and not few took advantage of them very well.

For example, the girl of the house took a liking to the nice, docile little black man, and could even teach him to read and write. In the domestic context, the skillful, respectful, docile Negro was intimate with the father of the house and got to know him even certain secrets, such as his affairs with the black women, from which, not infrequently, “bastard” children were born within the family.

The black man, a connoisseur of herbs, prepared a concoction that cured the master of pain. And within this intimacy, the master practically began to see him as part of the family. He gave him chores, shared certain secrets with his slave and thus, sometimes, this one, already old, earned manumission, or the letter of freedom.

Within the master’s house, living together as a domestic slave, the black man achieved advantages, which he often took advantage of and which made him advance in social life, even while maintaining his status as a slave.

Domestic slavery generated a certain culture and within it, a level of permissibility, of which the black could take advantage. This allowed him to become part of society, even with all the disadvantages of a slave society.

Meanwhile, in the United States, after the Civil War, slavery was abolished in the North, but they had to continue to struggle with it in the South. Blacks escaped to the North, where they became free, but not infrequently, they left behind relatives who remained as slaves in the South.

Not in Cuba, where slavery was a homogeneous system throughout the island. Therefore, when the laws that attenuated it began to appear, such as the so-called Law of Free Wombs, until its official abolition in 1886, this had a national effect.

Of course, slavery began to disappear after a long process, in which Spain abolished it, as a first step, giving freedom to blacks who had fought, on both sides, during the First War of Independence (1868/1878) until it was finally abolished in a general way in 1886.

However, in America, slavery took color. And with it came racism and racial discrimination, which were not born with capitalism, but which hit it very well, as an instrument of power and exploitation.

Therefore, slavery disappeared, but racism and discrimination, which it engendered, for more than 400 years, remained imbricated within the structure of Cuban society. And so, since the middle of the 19th century, a society with a racist, mestizo and white hegemonic culture began to emerge. Therefore, racism, racial discrimination and white hegemony, within our mestizo society, have not yet been eliminated, although they have been attenuated.

Therefore, the Revolution that triumphed in 1959, found a society in which there was a well-defined structure. The so-called whites had the power, they always had it. Mestizos were, more or less, in an intermediate position, some few had access to power; the blacks were, almost always, in the subsoil of society. This is the result of a distribution of wealth that colonialism inaugurated and Cuban-dependent capitalism took charge of solidifying.

In Cuba, poverty was also massively white, but wealth was never black, and almost never mestizo.

After Fidel, almost since the triumph of the Revolution, began to treat it systematically, racism, racial discrimination and white racial hegemony have not disappeared.

The social policy that the revolution inaugurated in 1959 has always had a profoundly humanist character, but, from the beginning, it focused only on poverty, making no differentiation among the poor, treating poverty as unique, which was never homogeneous, without differentiating within it, according to skin color.

Would it have been possible, so early on, to have considered poverty, taking into consideration its differences and levels, according to skin color?

I don’t think so. I believe that this would have greatly complicated the fight against racism and racial discrimination that was beginning at that time. I believe that if Cuban society was not prepared, as it became clear, to assimilate Fidel’s speech against racism, much less would it have been prepared if, in addition, the existing differences in the levels of poverty according to the color of the skin had been introduced. I believe that this would have implied the introduction of a certain level of affirmative action, for which whites, mestizos, and not even blacks themselves were prepared.

That is why, I believe, social policy, in Fidel’s speeches, began by demanding employment for blacks, while everything else: health, education, culture and sports and social security, fell under its own weight and equally for all. When there was an equal distribution for all, blacks and mestizos got what, in general, had never been given to them before. Because the blacks and, to some extent, the mestizos, had never enjoyed free and quality education and much less, blacks, health. Sport was the opposite. And so, it began to produce a distribution of national wealth, which the nation had never known. And, within which, to blacks and mestizos, almost never, almost nothing had touched them. For this reason, although skin color was not taken into account, blacks and mestizos benefited as never before in the history of the nation. For this reason, it was not difficult for blacks and mestizos to understand that the revolution was their revolution and that Fidel had been concerned and fought for their welfare.

This is one of the aspects that, in the last 40 years, we have managed to fine-tune. Without yet reaching, as such, so-called Affirmative Action. Forms of the latter have been gradually appearing in Cuba, but almost indirectly. And we are still in the process of perfecting the initiated path. What is beginning to take shape, by means of concern and an occupation by the political leadership that there is no one left behind.

Having demonstrated that race does not exist, that it is a social invention. But that, however, color does, and that, in our country, after 500 years [M1] of colonialism, skin color continues to behave as a variable of social differentiation. Against which, we have proposed to fight.

This tells us why, since the beginning of the Republic, in Cuba, there were black and mestizo societies. It is true that they acted within a racist and discriminatory context, which made them respond to it. But they also functioned as fraternal societies, which helped the black and mestizo members to train themselves, on the basis of free courses for their young people, social and cultural activities, which in general helped this population to face the problems of inequality. Sometimes they made it easier to find employment and, in general, helped blacks and mestizos to have a certain recognized social presence.

However, after the triumph of the Revolution, these societies began to disappear, as a result of the consideration that they were not necessary, since the revolution assumed the defense of blacks and mestizos and that they could contribute more to the racial division within the Cuban society.

However, paradoxically, at the same time, the Spanish Societies, considered as white, were maintained in Cuba until today. The question still remains unanswered: Why did the black ones disappear and these, coincidentally, of whites, did not?

This is something that has brought controversy and uneasiness, although not only among blacks and mestizos. Today, it is even questioned whether black and mestizo societies should not reappear. Today, the subject tends to re-enter the debate. Especially because the problem of racism and racial discrimination has not yet been completely overcome.

But the blacks and mestizos, from the beginning, did not make any demands and everything remained as it was.

Here in Cuba, after 60 years of a radical Revolution, of profoundly humanist essence and of an extraordinary struggle against poverty, injustice and inequality, to the very edges of egalitarianism, still, from the point of view of social position, access to certain resources and certain advantages in social life, it is not the same to be white, black or mestizo. This is not a burden, but it responds to a structural dysfunctionality that even Cuban society drags along and is capable of reproducing.

In particular, the so-called Special Period showed that the economic crisis had not affected all racial groups equally. Blacks and mestizos suffered the most. This became evident.

Our government also realized that the difficulties with racism, which surfaced with some force during the Special Period, were indicating that it was a problem that, having been considered as solved, was not really solved; or at least, it was not being solved at the pace that many had imagined, but rather, racism had been hidden in the midst of the difficulties experienced during those years of the mid-eighties and early nineties.

Until then, there had been a long period of general silence on the subject, which Fidel broke on several occasions, both inside and outside Cuba, but without achieving then that the racial issue would definitely occupy its rightful place in the struggle for a better society in Cuba today.

I think that, in this, we have to start from the existence of inequalities, to reach real equality. Unfortunately, inequality is what we find at every step. Equality is a social project, not yet achieved by Cuban society as a whole.

Therefore, we should not mechanically assume that all Cubans are equal, because that was also wielded as a hypocritical slogan of Republican Cuba.

All Cubans are not yet equal. We are equal before the law, but not socially. They are two very different phenomena. Equality before the law has been achieved. But achieving social equality is a much longer and more complex process. Equality before the law is not social equality. It is, perhaps, only a step towards the latter.

Today, there is a clear awareness that we must continue to fight against inequality, pursuing it to those places where marginality still assaults members of our society and not only blacks and mestizos. Therefore, the work with the so-called Community projects gains unusual strength.

It is possible to observe the Party and the government, extraordinarily busy, mobilizing qualified human forces and resources, which are put in the function of the solution of multiple material, spiritual and social problems, which the Cuban society still has to overcome.

This task of the Community Projects is strongly intertwined with the Government Resolution, which serves as an instrument for the fight against racism and racial discrimination.

Fidel had already become aware of all this and began to take action. He conducted in-depth investigations in several underprivileged neighborhoods on the situation of sometimes marginalized sectors.

It was also, then, when the experience of the so-called Social Workers was carried out; most of them blacks and mestizos, which resulted in many young people, who neither studied nor worked (it is said that there were 80,000 in Havana) reaching the Universities. Those that had been “whitened” during the Special Period.

Then, at the end of the eighties, we took up the subject again. Which, I think, is the period in which we find ourselves now, at the height of 2021.

Previously, during the 20’s and 30’s, above all, the racial issue had been present in the written media, especially in the press of the time. Personalities such as Juan Gualberto Gómez, Arredondo, Guillen, Deschamps, Chailloux, Ortiz, Portuondo, and others, had produced important texts on the subject. And they managed to keep it within the debate in the press of the time, even in Diario de la Marina.

But that momentum was not maintained and by the triumph of the revolution, it had almost disappeared.

But, since the 80s, many publications of books, articles, essays, documentaries, and research in some universities began to reappear. Cinema frequently brought up the subject, as well as plastic arts, theater and literature. Discussion groups and community projects arose, which today deal with the racial issue and have given it a growing presence in the national culture and life. In fact, it had been years since the subject had such an important place in the national debate.

Miguel Díaz Canel, who dealt with the issue before becoming president and continues to do so now, together with the Aponte Commission of the UNEAC. The Aponte Commission replaced the group “Como agua para chocolate” (Like water for chocolate), led by Gisela Arandia. She was the initial promoter of the racial debate in UNEAC. Already, previously, the racial issue had been taken to the party and later located in the National Library, but it was, finally in the UNEAC, where it found its definitive location. And now it is unfolding. Through the work of the aforementioned Aponte Commission.

All this movement has concluded, with the appearance of a Governmental Resolution, above mentioned, where the guidelines for the attention and treatment of the racial topic at national level are proposed. With the presence, also, of all those groups interested in the subject. Aspects of participation, which still require development.

However, I consider that, although we have made progress, we are still far from giving the racial issue the impetus it requires. There are still many situations to be resolved.

Although our society is culturally mestizo, the presence of racism, racial discrimination and a certain [amount of] white hegemonism are still felt in the following matters:

-Inequalities, persist within the racial population structure, formed by whites, blacks and mestizos. This is not a burden, but a phenomenon of social dysfunctionality, which even Cuban society is capable of reproducing.

-Differences in access to employment also persist. With privileges for the white population, in the most important and better-remunerated jobs: tourism, corporations, state positions, etc. Not so in political positions, especially within the party, Popular Power and Mass Organizations, where the participation of blacks and mestizos is becoming more present.

-Differences by color, in the access to possibilities of higher studies, Universities, masters, doctorates, etc.

-Racism, prejudice and discrimination against the black and mestizo population, which tends not to manifest itself aggressively, but are still present.

-Marked presence of an insufficient number of interracial marriages. With a marked tendency towards racial mixing among young people, which is indicative of the fact that young people are shedding their prejudices.

Discrimination in the mass media, mainly on television, in which white faces have dominated, and only recently have black and mixed-race faces begun to appear. In response to a recent specific claim made by Army General Raúl Castro in the National Assembly.

-Our written press barely reflects the problems of the racial issue. There is no systematic treatment on the subject. Nor is there any promotion of writers who deal with the subject. Almost never in our press there is an article that deals with the subject.

-Our Political and Mass Organizations do not debate the racial issue. They do not promote its discussion, nor do they consider it in their work agendas.

-Discrimination in classical ballet.

-Racist jokes and expressions abound in cabaret activities.

-Only recently, the teaching of history has begun to reflect the place of blacks and mestizos in the formation of our national history. And teachers are being prepared to address it.

-Until very recently, the bibliography used, with honorable exceptions, and very well known, did not reflect the role of the black and mestizo population in the construction of our nation. Now a strong and arduous bibliographic work is being carried out by the Ministries of Education, aimed at solving this insufficiency of vital consideration for the teaching of history.

-There is neither a Social History of the black nor of the black woman, produced in Cuba.

-Even dealing with the racial issue, at any level and in any social space, can generate certain discontent, prejudices and discomfort.

-It is only recently that our national assembly has begun to present a structure that almost faithfully reflects the racial composition of Cuban society.

-For those who deal with the subject in a systematic way, their discussions are not disclosed, always remaining in the frameworks of groups and interested persons.

-In Cuban schools there is no mention of color, leaving it to personal spontaneity to deal with the problem.

-In our universities, the racial issue is hardly studied. Nor does it appear in the teaching curricula.

-Our academic research hardly refers to the racial issue sufficiently and it is practically absent from the student scientific work.

-Only recently, we have begun to observe that an effort is being made to attend to the racial composition of workgroups, activities, or situations in which the black and the mestizo should be represented. This can be seen with particular emphasis on television.

-In reality, our statistics, social, economic and political, are colorless. Throwing centuries of national history into the dustbin. They fail to appreciate where the problems lie.

-Our economic statistics do not allow to cross color, with variables of employment, housing, wages, income, etc. This prevents us from investigating, in-depth, how the standard of living of the different racial groups is advancing. Especially those who were previously disadvantaged.

We consider that as long as the racial issue is not treated systematically and coherently, at a comprehensive level, and is reliably reflected in our statistics and in our media, we cannot aspire to socially advance the country on the subject.

Our inherited culture is racist; that is to say, the practice of racism is cultural, instinctive, responding mainly, but not only, to inherited mechanisms that work, not infrequently, unconsciously.

Therefore, until the issue enters education, is strongly discussed socially, is part of the systematic work of the media and is statistically considered, we cannot expect it to become part of the culture, nor can we aspire to advance in it, banishing it from the usual forms of behavior of citizens in our country.

The fact is that the absence of attention, almost generalized, for a long time, of the racial issue, has very negative consequences. This is because its knowledge, understanding and consideration at the social level, as something that harms the Cuban nation. This is a very serious problem to overcome if we want our society and its culture to advance in an integral way, guaranteeing the success of the social project of the revolution.

June 30, 2021.

CENSOS, COLOR DE LA PIEL Y ANALISIS SOCIAL.

Esteban Morales

Autor: Esteban Morales Domínguez

Junio 30 del 2021.

Aunque mueve todavía a muchos prejuicios, incomprensiones y desafíos, no queda más remedio que atender al color de la piel. Sobre todo, en su consideración dentro de los Medios y las Estadísticas nacionales.

La sociedad cubana, es una sociedad multirracial, o más bien, multicolor, mestiza. Y esa realidad tiene que ser registrada estadísticamente. No manejando el Censo como un asunto, simplemente numérico, sino demográfico cultural.

Se trata de que el color es una herencia de la Esclavitud. Que no es posible soslayar, pues esta marca desde sus orígenes a la sociedad cubana actual.

Cuando los españoles llegaron a Cuba, en 1492, lo hicieron con credenciales de blancos y así se quedaron. Los que vinieron por voluntad propia, lo hicieron buscando una fortuna, que no pocas veces encontraron.

Pero España no es Blanca. Colonizada por los árabes, durante 800 años, se hace imposible considerarla como tal. Aún y cuando al español no asume esa identidad.

Entonces, los colonizadores de nuestro Archipiélago, no eran blancos. En ser blancos no consistía su poder, sino, el haber llegado con la cruz y con la espada.

Llegaron a un territorio de indígenas, de baja cultura y solo los utilizaron para encontrar oro. Los explotaron de manera inmisericorde y su masa poblacional, no duro mucho tiempo, aunque todavía en Cuba, tenemos representantes de esa población originaria.

También vinieron chinos, traídos, por medio de un sistema de contratos, que los convertía en esclavos. Los llamados culíes, que desde entonces agregaron su belleza a la población de la Isla, integrando nuestra nacionalidad. Ésos tres grandes grupos, fueron los que formaron la población cubana. Después se sumaron otros, antillanos, aunque no en la magnitud de los primeros, fundiéndose también con nuestra población.

Aunque la Corona Española, puso reglas para el cuidado de la población indígena; de todos modos, la ambicion de los colonizadores, junto al Régimen de las Encomiendas y la esclavitud, redujeron esa población a su mínima expresión.

En poco más de 100 años Los llamados Tainos, Siboneyes Y guanahatebeyes, casi desaparecieron, pues no eran de una cultura avanzada, como si ocurría para el resto de América. Culturas, Aztecas, Mayas, Toltecas, etc. Las que sí, culturalmente, no tenían, prácticamente, nada que envidiar a las culturas europeas de su tiempo.

Pero la población indígena existente en el Archipiélago cubano, carecía de esa fuerza, que da el pertenecer a una cultura superior.

Junto con los españoles, vinieron los primeros negros. No de Africa, sino directamente, de España. A esos negros se les llamaba “Ladinos”, eran esclavos en España, sabían hablar el idioma y tenían cierta cultura, adquirida en el trabajo de servidumbre, para lo cual, también llegaron a Cuba. Pero lo hicieron en número reducido.

La inmensa mayoría de los negros que llegaron a Cuba, masivamente, lo hicieron después, como resultado del comercio de esclavos. Y de modo masivo, a partir de la Revolución Haitiana de 1791.Se asentaron en el Extremo Oriental de La Isla. Teniendo un gran impacto cultural, pues venían acompañados de sus amos franceses. Asi llego a Cuba, la contradanza francesa y la llamada Tumba Francesa. Todo lo cual, conocemos como antecedentes de nuestros bailes nacionales, el Danzón.

Por la región oriental, entraron los grupos antillanos, para participar en la producción azucarera, de aquí la mezcla que caracteriza a esa región, que cubre hasta la actual provincia de Camagüey, donde encontramos muchos descendientes de franceses (haitianos), o de ingleses (jamaicanos) y otros grupos antillanos. Lo cual, hizo más complicada la situación de la discriminación racial en las regiones mencionadas.

Sin embargo, no dieron lugar a la formación de minorías, como en los Estados Unidos, sino que se fundieron con la población cubana, manteniendo sus apellidos ingleses y franceses.

Entonces, los negros, fueron traídos como esclavos a Cuba, para el trabajo de las construcciones primero y el trabajo de la producción azucarera después, dentro de un régimen colonial ya organizado. Decir negro en Cuba, era decir esclavo.

Estos esclavos, prácticamente, desde el siglo XVI, podían comprar su libertad.

Como los españoles llegaron, hombres solos. De manera inmediata, comenzaron a mezclarse con las indias y las negras, iniciándose así el mestizaje de la Isla. Y dentro de un mestizaje complejo, pues estaba formado por personas libres o esclavas, mestizas o negras. No así los blancos españoles, que nunca sufrieron la condición de esclavitud.

A diferencia de los negros que fueron traídos al territorio de las Trece colonias de América del Norte, lo que después fueron los Estados Unidos de América; los llegados, también traídos de África como esclavos al territorio mencionado, estos no podían hablar sus lenguas, sino solo el inglés, no podían practicar sus religiones, ni sus culturas. No les estaba permitido por los colonizadores. En tal sentido el régimen esclavista procedente de Inglaterra, resultaba más duro, con una separación casi absoluta entre negros y blancos. Que es lo que ha terminado caracterizando a la sociedad estadounidense.

A los negros traídos a Cuba, también de Africa, la colonización española, les permitían hablar sus lenguas, adorar sus dioses y practicar sus culturas.

Se trataba, de que, por razones históricas y también culturales, los españoles eran más proclives a la convivencia con las prácticas culturales de los esclavos en Cuba y con los colores diferentes.

A diferencia de América del Norte, en Cuba, los españoles, convivían mejor con las diferencias en el color. A lo que contribuía también las diferencias que introducía en la esclavitud del negro, la existencia de una esclavitud doméstica y otra de plantación.

En Cuba esto no tuvo lugar, pero en la colonización americana, venia un tipo de colonizador, que no teniendo dinero para correr con los gastos de su traslado a Anerica, solicitaba un préstamo, que le obligaba a trabajar, prácticamente como un esclavo o siervo. Una vez pagada la deuda del préstamo, recibía un pedazo de tierra, convirtiéndose en un granjero pobre. Salvo la existencia de algunos esclavos, que no vivían en el barracón y cultivaban un pequeño pedazo de tierra, para abastecer la casa del amo, en Cuba nunca hubo siervos como tal.

En la plantación, el negro debía trabajar de sol a sol, bajo el látigo del Capataz o Mayoral; mientras que, en el trabajo doméstico, sus tareas se desplegaban en la casa del hacendado esclavista, imbricadas con las actividades del servicio a la familia. Allí podía ser cochero, cocinero, costurero, lavaba y planchaba, ponía la mesa, arreglaba la ropa del amo y le hacía un brebaje, cuando este enfermaba, etc. Realizando labores, que, prácticamente lo preparaban para hacerse de un oficio, por si algún día lograba obtener su libertad, comprada o manumitido.

El contacto con la familia los instruía y dotaba de cierta cultura, que lo diferenciaban del esclavo de la plantación. A quien no estaba permitido más que trabajar en el corte de la caña, o la producción de azúcar.

El negro, donde quiera que estuviese, no dejaba de ser esclavo, y el cepo, ante la desobediencia más mínima, estaba sobre él, como Espada de Damocles. Pues el amo blanco, no les permitía aquellas libertades, que pudiesen inculcarle alguna cultura de independencia, lo cual se vigilaba mucho. Pero, en el trabajo doméstico, de hecho, las ventajas, las tenían y no pocos las aprovechaban muy bien.

Por ejemplo, la niña de la casa, le tomaba cariño al negrito simpático, dócil, y hasta podía enseñarlo a leer y escribir. En el contexto doméstico, el negro hábil, respetuoso, dócil, intimaba con el padre de la casa y llegaba a conocerle hasta ciertos secretos, como sus andadas con las negras, de las cuales, no pocas veces, salían hijos “bastardos” dentro de la familia.

El negro, conocedor de las hierbas, preparaba un brebaje que le curaba un dolor al amo. Y dentro de esa intimidad, este, prácticamente, comenzaba a verlo como parte de la familia. Le daba tareas, compartía ciertos secretos con su esclavo y así, a veces, este, ya viejo, se ganaba la manumisión, o la carta de libertad.

Dentro de la casa del amo, conviviendo como esclavo doméstico, el negro lograba ventajas, que no pocas veces, aprovechaba y que lo hacían avanzar en la vida social, aun manteniendo su condición de esclavo.

Es que la esclavitud doméstica, generaba cierta cultura y dentro de ella, un nivel de permisibilidad, de la cual el negro podía aprovecharse. Lo cual le permitía, irse introduciendo en la sociedad, aun con todas las desventajas de una sociedad esclavista.

Mientras, en los Estados Unidos, posterior a la Guerra Civil, la esclavitud fue abolida en el norte, pero había que seguir bregando con ella, en el sur. Los negros escapaban al Norte, donde devenían en libres, pero no pocas veces, dejaban atrás familiares que se mantenían como esclavos en el Sur.

En Cuba no, la esclavitud era un sistema homogéneo a nivel de toda la Isla. Por lo que, cuando comenzaron a aparecer las leyes que la atenuaban, cómo la llamada Ley de Vientres libres, hasta su abolición oficial en 1886, esto tuvo un efecto nacional.

Claro, la esclavitud comenzó a desaparecer, a partir de un largo proceso, en el que España la abolió, como primer paso, dándoles la libertad a los negros que habían peleado, de ambos lados, durante la Primera Guerra de Independencia (1868/1878) hasta que finalmente, fue abolida de manera general en 1886.

No obstante, en América, la esclavitud tomo color. Y con ella llego el racismo y la discriminación racial, que no nacieron con el capitalismo, pero que le pego muy bien, como instrumento de poder y explotación.

Por ello, la esclavitud desapareció, pero el racismo y la discriminación, que ella engendro, por más de 400 años, quedaron imbricados dentro de la estructura de la sociedad cubana. Y así, desde mediados del siglo XIX, comenzó a surgir una sociedad, con una cultura racista, mestiza y de hegemonía blanca. Por lo que, el racismo, la discriminación racial y el hegemonismo blanco, dentro de nuestra sociedad mestiza, aún no han podido ser eliminados, aunque si atenuados.

Entonces, La Revolución que triunfo en 1959, se encontró con una sociedad, en la cual, existe una estructuración bien definida. Los llamados blancos tienen el poder, lo tuvieron siempre; los mestizos están, más o menos, en una posición intermedia, algunos pocos tuvieron acceso al poder; los negros están, casi siempre, en el subsuelo de la sociedad. Lo cual es resultado de una distribución de la riqueza, que el colonialismo inauguro y el capitalismo dependiente cubano se encargó de solidificar.

Es que, en Cuba, la pobreza fue también, masivamente blanca, pero la riqueza nunca fue negra, y casi nunca mestiza.

Después de que el Cro. Fidel, casi desde el triunfo de la Revolución, lo comenzó tratando de manera sistemática; el racismo, la discriminación racial y la hegemonía racial blanca, no han desaparecido.

La política social que la revolución inauguro desde 1959, ha tenido siempre un carácter profundamente humanista, pero, desde el principio, se enfocó solo en la pobreza, no haciendo diferenciación entre los pobres, tratando como única la pobreza, que nunca fue homogénea, sin hacer diferenciación dentro de ella, según el color de la piel.

¿Habría sido posible, de manera tan temprana, haber considerado la pobreza, tomando en consideración sus diferencias y niveles, según el color de la piel?

Me parece que no. Creo que ello habría complicado sobremanera la lucha que se iniciaba entonces, contra el racismo y la discriminación racial. Púes creo, que si la sociedad cubana, no estaba preparada, como se puso de manifiesto, para asimilar el discurso de Fidel contra el racismo; mucho menos lo habría estado, si, además, se hubieran introducido las diferencias existentes en los niveles de la pobreza según el color de la piel. Creo que eso hubiera implicado, introducir cierto nivel de acción afirmativa, para lo cual blancos, mestizos y ni los propios negros, estaban preparados.

Razón por la cual, creo, la política social, en los discursos de Fidel, comenzó, por reclamar empleo para los negros; mientras, que todo lo demás: salud, educación, cultura y deportes y seguridad social, cayeron por su propio peso y de manera igualitaria para todos. Al producirse una distribución para todos por igual, a negros y mestizos, les toco, lo que, por lo general, nunca les había tocado. Porque los negros y en alguna medida los mestizos, nunca habían disfrutado de educación gratuita y de calidad y mucho menos, los negros, de la salud. El deporte, fue la contra. Y asi, se comenzó a producir una distribución de la riqueza nacional, que la nación nunca había conocido. Y, dentro de la cual, a negros y mestizos, casi nunca, les había tocado casi nada. Razón por la cual, aunque no se tuvo en cuenta el color de la piel, de todos modos, negros y mestizos, resultaron beneficiados, como nunca antes en la historia de Nación. Razón por la cual, a negros y mestizos no les resulto difícil entender, que la revolución era su revolución y que Fidel, se había preocupado y luchado por su bienestar.

Tratándose lo anterior, de uno de los aspectos, que, en los últimos 40 años hemos logrado ir afinando. Sin llegar aun, como tal, a la llamada Acción Afirmativa. Han venido apareciendo paulatinamente formas de esta última en Cuba, pero de manera casi indirecta. Y aun nos encontramos en ese perfeccionamiento del camino iniciado. Qué comienza a perfilarse, por medio de una preocupación y una ocupación de la dirección política de que no haya nadie desamparado.

Habiéndose demostrado que la raza no existe, que es una invención social. Pero que, sin embargo, el color si, y que, en nuestro país, después de 500 años[M1] de colonialismo, el color de la piel, continúa comportándose como una variable de diferenciación social. Contra la cual, nos hemos propuesto luchar.

Lo que nos dice, porque, desde principios de la Republica, en Cuba, hubo sociedades negras y mestizas. Es cierto que las misma actuaban dentro de un contexto racista y discriminatorio, que las hacia responder a él. Pero que también, funcionaban como sociedades fraternales, que ayudaban a la membresía negra y mestiza a capacitarse, sobre la base de cursos gratuitos a sus jóvenes, actividades sociales y culturales, que en general, ayudaban a esta población a enfrentar los problemas de la desigualdad. A veces facilitaban conseguir empleo y en general, ayudaban a los negros y mestizos a tener una cierta presencia social reconocida.

Sim embargo, al Triunfo de la Revolución, estas sociedades, comenzaron a desaparecer, como resultado de la consideración de que no eran necesarias, pues la revolución asumía la defensa de negros y mestizos y de que las mismas, podían contribuir más a la división racial dentro de la sociedad cubana

Sin embargo, paradójicamente, al mismo tiempo, se mantuvieron las Sociedades Españolas, consideradas como blancas, que en Cuba se mantienen hasta hoy. Aún queda sin responder la pregunta: ¿Por qué la de los negros desparecieron y estas, casualmente, de blancos, ¿no?

Se trata de algo que ha traído polémica y malestar, aunque no solo entre negros y mestizos. Hoy, incluso, se cuestiona, si las sociedades de negros y mestizos, no debieran reaparecer. Hoy el tema, tiende a entrar de nuevo en el debate. Sobre todo, porque el problema del racismo y la discriminación racial, aún no están totalmente superados.

Pero los negros y mestizos, desde el principio, no hicieron ningún reclamo y todo quedo asi.

En Cuba, después de 60 años de una Revolución radical, de esencia profundamente humanista y de una lucha extraordinaria contra la pobreza, la injusticia y la desigualdad, hasta los mismos bordes del igualitarismo; todavía, desde el punto de vista de la posición social, del acceso a determinados recursos y de ciertas ventajas en la vida social, no es lo mismo ser blanco, negro o mestizo. Lo cual no es un lastre, sino que responde a una disfuncionalidad estructural, que aun la sociedad cubana, arrastra y es capaz de reproducir.

En particular, el llamado Periodo especial, demostró que la crisis económica no había afectado por igual a todos los grupos raciales. Siendo negros y mestizos los que más lo sufrieron. Lo cual se hizo evidente.

Nuestro Gobierno, además, se percató, de que las dificultades con el racismo, que afloraron con cierta fuerza durante el Periodo Especial, estaban indicando, que se trataba de un problema que, habiéndolo considerado como resuelto, realmente no lo estaba; o al menos, no se estaba solucionando, al ritmo que muchos habían imaginado, sino que más bien, el racismo, se había ocultado, en medio de las dificultades vividas durante esos años, de mediados de los ochenta y principios de los noventa.

Había tenido, hasta entonces, un largo periodo de silencio general sobre el tema, que Fidel rompió en varias ocasiones, tanto dentro, como fuera de Cuba, pero sin lograr entonces, que el tema racial, ocupara definitivamente el lugar que le corresponde en la lucha por una sociedad mejor en la Cuba actual.

Pienso que, en ello, tenemos que partir de la existencia de las desigualdades, para llegar a la igualdad real. Lamentablemente, la desigualdad es lo que nos encontramos a cada paso. La igualdad, es el proyecto social, no alcanzado aún por la sociedad cubana como totalidad.

Por tanto, no debemos asumir de forma mecánica, que todos los cubanos somos iguales; porque eso también fue esgrimido como un hipócrita slogan de la Cuba republicana.

Todos los cubanos, aun no somos iguales. Lo somos ante la ley, pero no socialmente. Son dos fenómenos muy diferentes. Ha podido ser lograda la igualdad ante la ley. Pero alcanzar la igualdad social, es un proceso, mucho más largo y complejo. Igualdad ante la ley, no es igualdad social. Sino, solo, tal vez, un paso, para llegar a esta última.

Hoy, se observa que existe una conciencia bastante clara de que contra la desigualdad hay que continuar luchando, persiguiéndola hasta aquellos lugares en que la marginalidad aun agrede a miembros de nuestra sociedad y no solo a negros y mestizos. Por lo que el trabajo con los llamados proyectos Comunitarios gana fuerza inusitada.

Pudiéndose observar al Partido y al gobierno, extraordinariamente ocupados, movilizando fuerzas humanas calificadas y recursos, que se ponen en función de la solución de múltiples problemas materiales, espirituales y sociales, que la sociedad cubana aún debe superar.

Esta tarea de los Proyectos Comunitarios, se entrelazan fuertemente de la Resolución Gubernamental, que sirve de instrumento para la lucha contra el racismo y la discriminación racial.

Ya Fidel se había percatado de todo ello y comenzó a realizar acciones. Orientando profundas investigaciones, en varios barrios desfavorecidos, sobre la situación de sectores, a veces marginados.

Fue también, entonces, cuando se realizó la experiencia de los llamados Trabajadores Sociales; la mayoría negros y mestizos, que trajo como resultado, que muchos jóvenes, que ni estudiaban ni trabajaban, (se dice que eran 80,000 en La Habana) llegaran a las Universidades. Las que se habían “blanqueado”, durante el Periodo Especial.

Entonces, a partir de finales de los años ochenta, retomamos nuevamente el tema. Que pienso, es el periodo en que nos encontramos ahora, a la altura del 2021.

Con anterioridad, durante los años 20 y 30, sobre todo, el tema racial había tenido presencia en los medios escritos, especialmente, en la prensa de la época. Personalidades como Juan Gualberto Gómez, Arredondo, Guillen, Deschamps, Chailloux, Ortiz, Portuondo, y otros, habían producido textos importantes sobre el tema. Y logrado mantenerlo dentro del debate en la prensa de la época, incluso en el Diario de la Marina.

Pero ese impulso no se mantuvo y al triunfo de la revolución, había casi desaparecido.

Pero, ya desde los años 80, comenzaron a reaparecer muchas publicaciones de libros, artículos, ensayos, documentales, e investigaciones en algunas universidades. Un cine que frecuentemente traía a colación el tema, la plástica, el teatro y la literatura también. Surgieron Grupos de Debate y Proyectos Comunitarios, que atienden hoy el tema racial y que lo han dotado de una creciente presencia dentro de la cultura y la vida nacional. En realidad, hacia anos, que el tema no tomaba un espacio tan importante en el debate nacional.

Comenzaron, entonces, las reuniones con el Cro. Miguel Díaz Canel, que atiende el tema, antes de ser presidente y lo continúa haciendo ahora, junto a la Comisión Aponte de la UNEAC, que sustituyó al Grupo, “Como agua para chocolate”, dirigido por Gisela Arandia. Que fue la promotora inicial del debate racial en la UNEAC. Ya, con anterioridad, el tema racial había sido llevado al partido y posteriormente ubicado en la Biblioteca nacional, pero fue, finalmente en la UNEAC, donde encontró su ubicación definitiva. Y ahora se desenvuelve. Por medio del trabajo de la arriba mencionada Comisión Aponte.

Todo este movimiento, ha concluido, con la aparición de una Resolución Gubernamental, arriba mencionada, donde se proponen las pautas para la atención y tratamiento del tema racial a nivel nacional. Con la presencia, también, de todos aquellos grupos interesados en el tema. Aspectos de participación, que aún requiere un desarrollo.

No obstante, considero, que, aunque hemos avanzado, todavía estamos lejos de darle al tema racial, el impulso que requiere. Púes quedan muchas situaciones aún por resolver.

Aunque nuestra sociedad, es culturalmente mestiza, la presencia del racismo, la discriminación racial y la de un cierto hegemonismo blanco, se hacen sentir todavía, en los asuntos siguientes:

-Las desigualdades, persisten dentro de la estructura racial poblacional, formada por blancos, negros y mestizos. No tratándose de un lastre, sino de un fenómeno de disfuncionalidad social, que aun la sociedad cubana, es capaz de reproducir.

-Persisten también las diferencias en el acceso al empleo. Con privilegios para la población blanca, en los aquellos más importantes y mejor remunerados: turismo, corporaciones, cargos estatales, etc. No así en los cargos políticos, en especial dentro del partido, el Poder Popular y las Organizaciones de Masas, donde la participación de negros y mestizos se está haciendo más presente.

-Diferencias por el color, en el acceso a posibilidades de estudios superiores, Universidades, maestrías, doctorados, etc.

-Racismo, prejuicios y discriminación, contra la población negra y mestiza, que tiende a no manifestarse de modo agresivo, pero que aún están presentes.

-Marcada presencia de una insuficiencia de matrimonios interraciales. Con una tendencia marcada a la mescla racial entre los jóvenes cual es indicativo de que los jóvenes se van desprendiendo de los prejuicios.

-Discriminación en los medios masivos, principalmente en la Televisión, en la que han dominado las caras blancas, pues solo recientemente, han comenzado a aparecer caras negras y mestizas. Ante un reclamo especifico, reciente, del Cro.General de Ejército, Raúl Castro en la Asamblea Nacional.

-Nuestra prensa escrita, apenas refleja los problemas del tema racial. No existiendo ningún tratamiento sistemático al respecto. Ni promoción de escritores que traten el tema. Casi nunca en nuestra prensa hay un artículo que aborde el tema.

-Nuestras Organizaciones Políticas y de Masas no debaten el tema racial. No promueven su discusión, ni lo consideran en sus agendas de trabajo.

-Discriminación en el ballet clásico.

-Chistes y expresiones racistas, abundan, en las actividades de los cabarets.

-Solo recientemente, la Enseñanza de la Historia ha comenzado a reflejar el lugar de negros y mestizos en la formación de nuestra historia patria. Y se están preparando profesores para abordarlo.

– Hasta hace muy poco, la bibliografía utilizada, salvo honrosas excepciones, muy conocidas, no reflejaba el papel de la población negra y mestiza en la construcción de nuestra nación. Ahora se realiza un fuerte trabajo bibliográfico arduo por los Ministerios de Educación, dirigido a solucionar esta insuficiencia de vital consideración para la enseñanza de la historia.

-No existe una Historia Social del Negro ni de la mujer negra, producida en Cuba.

-Aun tratar el tema racial, a cualquier nivel y en cualquier espacio social, puede generar cierto descontento, prejuicios y malestar.

-Solo recientemente nuestra asamblea nacional, ha comenzado a presentar una estructura, que refleja casi fielmente, la composición racial de la sociedad cubana.

-Para los que tratan el tema de manera sistemática, sus debates, no son divulgados, quedando siempre en los marcos de grupos y personas interesadas.

-En la escuela cubana no se menciona el color, dejando a la espontaneidad personal el comportamiento frente al problema.

-En nuestras Universidades apenas se estudia el tema racial. Ni aparece recogido en los currículos de enseñanza.

-Nuestras investigaciones académicas, apenas se refieren el tema racial de manera suficiente y el mismo está, prácticamente ausente, del trabajo científico estudiantil.

-Solo recientemente, comienza a observarse, que se hace un esfuerzo por atender a la composición racial de grupos de trabajo, actividades, o situaciones, en que el negro y el mestizo deben quedar representados. Esto se observa con especial énfasis en la televisión.

-En realidad, nuestras estadísticas, sociales, económicas y políticas, son incoloras. Lanzando al cesto de la basura siglos de la historia nacional. Soslayando apreciar donde están los problemas.

-Nuestras Estadísticas Económicas, no permiten cruzar color, con variables de empleos, viviendas, salarios, ingresos, etc. Lo que impide investigar a fondo, cómo avanza el nivel de vida de los diferentes grupos raciales. Especialmente de aquellos antes desfavorecidos.

Consideramos, que mientras el tema racial no sea tratado con sistematicidad y coherencia, a nivel integral y este fehacientemente recogido en nuestras estadísticas y en nuestros medios, no podremos aspirar a que socialmente, el país avance en el tema.

Es que nuestra cultura heredada, es racista; es decir, la práctica del racismo, es cultural, instintiva, respondiendo, principalmente, aunque no solo, a mecanismos heredados, que funcionan, no pocas veces, de manera inconsciente.

Por tanto, hasta que el tema no entre en la educación, sea fuertemente debatido socialmente, forme parte del trabajo sistemático de los medios y sea considerado estadísticamente, no podemos aspirar a que pase a la cultura, ni se avance en el mismo, desterrándolo de las formas del comportamiento habitual de los ciudadanos en nuestro país.

Es que la ausencia de atención, casi generalizada, durante mucho tiempo, del tema racial, tiene consecuencias muy negativas, para su conocimiento, comprensión y consideración a nivel social, como algo que perjudica a la nación cubana. Tratándose de un problema, muy serio a superar, si queremos que nuestra sociedad y su cultura avancen de manera integral, garantizando el éxito del proyecto social de la revolución.

Junio 30 del 2021.

Received by email from the author for translation.

Silencing the Study of Race and Equity

In the U.S., legislation is being passed to silence analyses on race and equity

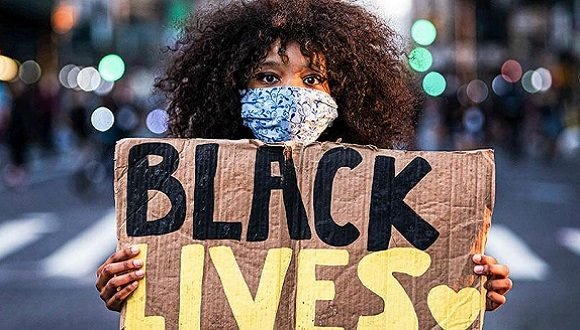

The same historical thread: slavery-Tulsa massacre-George Floyd and is intended to hide the facts to cover up scars and, above all, wounds still open and bleeding in the polarized U.S. society.

Author:

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Confronting America’s systemic racism Author: Joshua Lott Posted: 05/29/2021 | 10:49 pm

Is America a racist society? Yes. Absolutely and categorically so. Facts abound to exemplify the assertion. A review of some of the incidents of more immediate times reaffirms it.

However, it is not only the acts of violence, of police brutality, especially against Blacks and Latinos, nor the rise of extreme right-wing, xenophobic and fascistic groups and organizations, that show this visible trace. Neither do the economic and educational inequalities that undermine development opportunities.

In the first days of May, the governor of the state of Idaho, Republican Bradley Jay Little, signed a bill whose purpose is supposedly not controversial: to prohibit public schools and colleges from teaching that “any sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color or national origin is inherently superior or inferior”.

It might seem positive; however, this sidesteps, indeed, eradicates, conversations about race and equity, as if they have no relevance in a society where they remain one of the biggest and most divisive problems, rooted in a historical development that had as its roots the near annihilation and dispossession of native peoples and the enslavement of men and women forcibly brought from faraway Africa.

Idaho is not unique in the trend, as a dozen states, including Iowa, Louisiana, Missouri, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Rhode Island and West Virginia, have also introduced bills that would prohibit schools from teaching “divisive,” “racist” or “sexist” concepts.

According to a paper published by USA Today, such legislation attacks “critical race theory,” a movement of scholars and civil rights activists, which questions and critically examines how the legacy of slavery (in August 1619 the first cargo of enslaved Africans arrived on the shores of present-day U.S. territory) and systemic racism still affects American society today and are everyday experiences for people of African descent.

Thus, this legislative pattern – especially in Southern and Republican-dominated states – is seen as a backlash against teaching anti-racist lessons in schools, a barrier to learning true and hidden histories in order to entrench the racism against African descendants in the U.S. society.

The pattern is seen as a backlash against the teaching of anti-racist lessons in schools, a barrier to the learning of true and hidden histories to enthrone the socio-economic dominance of white elites, who also cover up class-based profiteering, whatever the skin color of the exploited.

Two key events

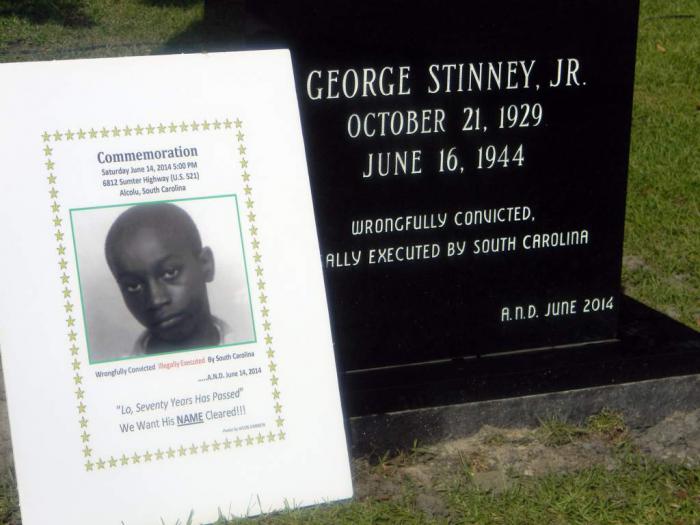

These final days of May mark two dates a century apart, the first anniversary of the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, when the relentless knee of policeman Dereck Chauvin squeezed his neck for more than eight minutes and prevented him from breathing. It was a crime that shook America and continues to shake it, and outraged the world. Then there is the centennial of a massacre of which very few in the northern nation are aware: the Tulsa massacre.

In Tulsa, Oklahoma, dozens of Black citizens were murdered -some estimates reach more than 300 victims of the racist barbarism of white mobs, joined by the police and the National Guard-, between the night of May 31 and June 1, 1921, in the Greenwood area, which was known as the Black Wall Street, due to the economic prosperity and intellectual development achieved by its inhabitants, and which was reduced to ruins and ashes in the fires.

Baptist minister and civil rights activist Jesse Jackson wrote in the Chicago Sun-Times: “Few even know about the massacre. It has not even been taught in Tulsa public schools until this year. Though a hundred years old, the massacre raises questions of justice and decency that

of justice and decency that America cannot avoid.”

Yet a significant part in size and power of the United States avoids it and does its best to sidestep it.

The detractors of critical race theory, the conservative elements that deny the existence of systemic racism in America, hoist its eradication and not only try to “discredit” it by calling it “Marxist”, above all they impute it to be a plan to “teach children to hate their country”, therefore, they are a threat to American society and the nation.

The Trump administration opposed the teaching of that history in public schools, asserting that it was “divisive and un-American propaganda.” Trump said, “Students in our universities are inundated with critical race theory. This is a Marxist doctrine that holds that America is an evil, racist nation, that even young children are complicit in oppression, and that our entire society must be radically transformed.”

Another reality

A recent study by Reflective Democracy, a group working to build a democracy in America that works for everyone “because it reflects who we are and how we live in the 21st century,” found that white men hold 62 percent of all elected offices despite being only 30 percent of the nation’s population, exercising minority rule over 42 state legislatures, the House of Representatives, the Senate and state offices from coast to coast.

The analysis added that women hold only 31 percent of the offices despite being 51 percent of the population and “people of color” hold only 13 percent despite constituting 40 percent of the population. It also recalled that 43 states in the Union are considering or have already passed laws that would allow them to apply voter suppression, which targets precisely those vulnerable segments – Blacks, Latinos, native Americans and women.

Some analysts recall that this wave against critical race theory only “crystallized” with Trump, but was awakened when Barack Obama came to the White House, which “was shocking and traumatic for people who had always imagined the United States as a white nation,” according to Adrienne Dixson, a professor at the University of Illinois and author of the book Critical Race Theory in Education.

On both sides, the debate has grown over the past year with the nationwide, ethnically diverse, age-group-wide activism of Black Lives Matter which burst onto the social scene of the national conservative organization Parents Defending Education, whose purpose is to confront what they consider “divisive and polarizing ideas in the classroom,” as Critical Race Theory sees it.

On their website Parents Defending Education released a study in which they claim that 70 percent of respondents said it is not important for schools to “teach students that their race is the most important thing about them.” that 74 percent opposed teaching students that whites are inherently privileged and that Blacks and other people of color are inherently oppressed. They also say that 69 percent opposed teaching in schools that America was founded on racism and is structurally racist. Likewise, they say and that 80 percent oppose the use of classrooms to promote student political activism.

Is American society polarized? Undoubtedly, and in my opinion, this is an extremely dangerous element, a boiling cauldron with no safety valve.

Show me your hair

Show me your hair, and I’ll tell you who you are?

The story aims to bring us closer to the life of Sarah Breedlove (who later became C.J. Walker when she remarried publicist Charles Walker and took his name for the business), the first African-American woman to achieve the status of a millionaire in the United States.

Author:

José Luis Estrada Betancourt |estrada@juventudrebelde.cu

March 8, 2021

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Madam C.J. Walker. Autor: MagaZinema Publicado: 08/03/2021 | 10:44 pm

I couldn’t help but think of my mother as soon as I started watching Madam C. J. Walker: Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J. Walker, the miniseries released by Netflix in 2020 and now broadcast by Cubavisión on Saturdays at around 9:15 p.m. And not only because the extraordinary actress Octavia Spencer brings my Juana to mind, but because the story she stars in and for which she was nominated for Emmy awards, brought me back to those years of my childhood in which so many times I found the mistress of my days girdled with a hot comb to smooth her hair soaked in fat smelly grease.

It frightened me that I had to try, by fire, to make them find her beautiful, sliding that red-hot iron through the bundle of strong and unruly hair that she inherited from our ancestors, to leave them shiny and straight. I preferred to leave so as not to witness a possible accident, an alternative that did not disappear when it was the turn of the curling iron and the curl began to bend in a more permanent way with a chemical treatment that does not even spare the scalp.

I didn’t even wonder then what would be wrong with natural hair. It seemed to me the most common thing in the world that some people wanted to “advance the breed”, or that, before inquiring about their health, they were concerned with finding out how the newborn had turned out: It is evident that I was not ready to understand then that the centuries of slavery, of colonialism, imposed a Eurocentrism that later capitalism and imperialism were in charge of accentuating, to the point that this racist concept, which is so discriminatory, is so impregnated in my mind, that I was not ready to understand then that the centuries of slavery, of colonialism, imposed a Eurocentrism that later capitalism and imperialism were in charge of accentuating, to the point that this racist concept, discriminatory, is so impregnated in us (still today) that it can be common that in many spaces what does not comply with the “white beauty” is taken as dirty, unkempt, inappropriate, unprofessional, and is associated with poverty and marginality.

Undoubtedly, the theory of the existence of human races (over time up to 63 were classified, although Cuba must have surpassed that figure with so many mulattoes, mulatos blanconazos, jabaos, capirros, Indians…) was a great “invention” for those who sought to establish their social and cultural supremacy. The truth is that, although scientifically it has been destroyed, the direct derivative of this concept: racism, has not disappeared at all.

Madam C. J. Walker: A Self-Made Woman, a story that aims to bring us closer to the life of Sarah Breedlove (who later became C.J. Walker when she remarried publicist Charles Walker and took his name for her business), the first African-American woman to achieve the status of millionaire in the United States, could speak more forcefully about all of this, but does not.

However, viewers should not think that they will get to know much about this revered figure by African Americans with the four 45-minute chapters that Netflix offers us, because suddenly we will find her as a notable businesswoman and philanthropist when in a scene filmed in broad daylight, we discover her dressed in beautiful blue, as if she were dressed for an Oscar award ceremony, protecting herself from the sun, strolling outside her mansion where she will be noticed by her neighbor Rockefeller.

Blair Underwood as Charles Walker.

“To whom God gave it…”, those who think I’m envious are probably thinking right now. It’s just that no divine force must have given her anything, but she certainly had to fight very hard to be able to create an empire in the cosmetics industry with hair products. How did a black woman, who came into the world in 1867, on a cotton plantation in Louisiana, orphaned at the age of seven, more than poor, without any education, a domestic servant who lost her knuckles washing, manage to impose herself in a United States living in full racial segregation, in that lamentable period (1877-1950) when more than 4,400 African-Americans were victims of terrible lynchings? How was she able to achieve this, subjected to men, as women were in the early years of the 20th century, and despised for her sex and her skin?

We will not know it from the series Madam C. J. Walker... It will remain as a pending task to approach in depth the existence of this totally unknown woman (at least for me). In this production, such historical context is just a postcard in the background. Of course, we will be moved by the image of some being hanging in a tree, but the story of the protagonist played by Spencer will move along other paths.

It begins when the beautiful Addie Munroe (Carmen Ejogo), a mulatto whose white genes gave her a long and abundant mane, is shown before Sarah with the “crecepelo”, a product that will not only solve her hair loss problems, but will also give her back, above all, her self-esteem. Seeing that it works, the future tycoon, excited, will propose to her savior to let her participate in the sale, but the first one, who in a “rapture of kindness” provided it, was not willing to give that miracle to darker people with bad hair. Just what writer Alice Walker (The Color Purple) calls “colorism” to describe that other expression of “internal” racism.

You don’t have to be too imaginative to know how the script will develop in the future: Sarah and Addie, who will give her one setback after another, will become bitter enemies, although those who are familiar with Madam C. J. Walker’s biography assure that this is one of the many licenses taken by the authors of the scripts, in order to provide the ingredients that would make the melodrama move forward in the right direction.

In fact, if one is to go by the events presented to us from the novel On Her Own Ground, by A’Lelia Bundles, on which this biopic is based, Madam C. J. Walker, rather than the enormous injustices that African-Americans had to face in the early 20th century, was made more difficult by Addie (who, let’s face it, ended up stealing her invention, which she miraculously copied and obtained) and the men around her – such as Charles Walker (Blair Underwood), the husband jealous of his wife’s success; and John (J. Alphonse Nicholson), the ungrateful husband of her daughter, Leila Walker (Tiffany Haddish). She becomes betrayed, even by some of the very women to whom she gave support and work…. Nothing, the series seems to reinforce the popular saying that there is no worse wedge than the wedge of one’s own stick.

In any case, the undeniable fact is that with her efforts Madam C. J. Walker overcame poverty, humiliation, discrimination, classist and sexist prejudices… to rise as a true exponent of the American dream and to honor the title of this dramatization that was released in March, just two months before George Floyd ended up dead under the knee of ex-cop Derek Chauvin.

For me, Madam C. J. Walker: A Self-Made Woman stands out, above all, for the superb performance of Octavia Spencer (who also serves as executive producer), ever so believable, ever so convincing. Yes, Spencer is an actress of the highest caliber. She reminded us again this Sunday thanks to the film Hidden Figures, which was put on by Arte 7. We saw her, as splendid as her two other co-stars (Taraji P. Henson and Janelle Monáe), also with her hair ironed, chemically straightened or in wigs, because that’s what is generally expected of black actresses and models on TV or in the movies. As beautiful as diversity is! But it is difficult to overthrow what has been coined for so many years in the sociocultural field.

The So-Called “San Isidro” Case

MONCADA Lectores

The So-Called “San Isidro” case

by Esteban Morales

by Esteban Morales

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

I believe that what is happening there is a consequence of not having taken care of four fundamental issues in time:

1- The marginal conditions of some of our neighborhoods in Havana.

2-The lack of attention or delay in recognizing and using the Social Sciences.

3- In spite of Fidel’s early warning, having neglected, for a long time, the racial question.

4-Some deficiencies in our political-ideological work.

On the last three points, I have warned enough.

But as a result of my warnings, I was never called to the Round Table, and when the faces of its protagonists appear, mine is never there. In spite of having been, individually, among those who have attended the Round Table the most.

None of those who used to publish me now publish me. They have not called me anymore to Cuban Television. Luckily TELESUR gave me a job.

I have also written many works on the racial question, three books and dozens of articles, always warning about the role that the Social Sciences should play and about the importance of ideological work. I am sure you have read some of them. In them, I have had to fight many battles, so that they do not accuse me of being a racist, accept my criticisms as necessary and do not believe that because I have traveled a lot to the United States, I have brought these things from there. Of which I have been accused more than a few times. Racism and discrimination were not brought by anyone, from anywhere. They are here, because they were born, with us, as a nation. And from here we will eliminate them someday. For the glory of all Cubans. We are already working on it within a Governmental Commission, presided over by Miguel Diaz Canel, President of the Republic.