Image: Morphart / El Colombiano.

I wish we didn’t have to write more about gender violence. I wish there was no need to organize activism days against it or designate orange days. I wish November was a month to celebrate its end and not to remember the many ways in which it manifests itself, how much it hurts. I wish it was no longer a problem, not here or anywhere. But it persists, also in Cuba. And hurts.

Therefore, because we cannot remain silent, because it is necessary to make their many faces visible and build collective solutions … again this column takes advantage of November – the month in which the 16 days of activism against gender violence begin – to carry out a series of works on the subject.

We intend to continue denouncing a conflict that affects one in three women in the world, even more in times of pandemic. But also explain its characteristics, contact experts, cross opinions and identify experiences of activism and confrontation. During the next few weeks, we will approach this phenomenon from different perspectives, we will explain some of its manifestations and above all, we will look for ways to put an end to it. Your doubts, opinions and experiences are welcome here.

When violence happens at home

Ana María Álvarez-Tabío Albo. Photo: Roberto Garaicoa

“Although we are sorry, gender violence is a phenomenon that is still present in Cuban society, also that which occurs in the family sphere. Consciously or unconsciously, we are a little complicit in its various manifestations, ” Ana María Álvarez-Tabío Albo, professor at the Law School of the University of Havana (UH), commented to Cubadebate.

Beyond physical attacks, he has many ways of expressing himself just as harmful. From the perspective of this jurist, when we passively observe verbal abuse, disqualification and other psychological aggressions that occur against women in the street, in a certain way we contribute to their permanence.

“All of this becomes even more acute inside the home. There are not so many witnesses there, but it is a palpable reality. There is gender violence in the family space in all its manifestations, including verbal, psychological, economic or patrimonial ”, the expert specified.

Leonardo Pérez Gallardo, president of the Cuban Society of Family Law, confirms this. During an interview with the Women’s News Service in Latin America and the Caribbean (SEMlac), she expressed that although physical abuse is the most obvious and identified, there are “other, more silent forms that do as much or more harm, and which are also present in Cuban daily life, such as psychological violence and manifestations of economic violence. “

Inside Cuban houses, all these attacks are observed that lead to the spiritual collapse of the victims and the disqualification of their potentialities. In addition, it is common for women to bear the greatest amount of domestic responsibilities and care work.

“They are the ones who usually stop working to take care of their children, the elderly and other family members, they are the ones who abandon their personal and professional projects and almost never receive the necessary collaboration. This implies that women in Cuba, although they have the same salaries as men, in the end, do not receive the same remuneration because they have to miss their jobs or leave them,” Álvarez Tabío explained.

Experts confirm it: gender violence is still a latent issue within many homes. Precisely because of the implications it has there, we decided to start this series of works by talking about one of the resources that could help put a stop to it. The project of the new Family Code, which our country is discussing these days, has a marked objective in confronting this matter.

“This Code is not for the violent”

Since version 22 of the draft of the new Families Code was published last September, the challenges facing legislation that defines, regulates and protects all households, regardless of their differences, have been high points on the agendas. media, political and of course, public.

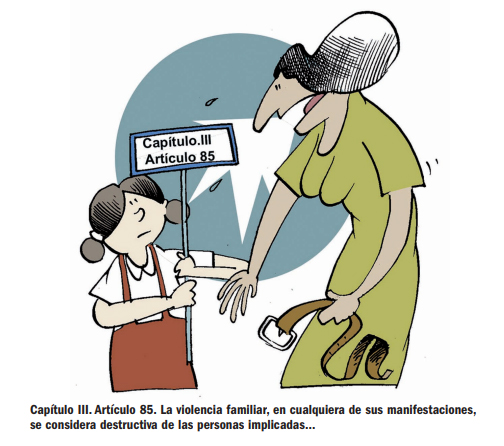

The document put up for discussion is in line with article 85 of the Constitution of the Republic, according to which “family violence, in any of its manifestations, is considered destructive of the people involved, families and society, and it is sanctioned by law “.

Therefore, it expresses the right to a family life free of violence in any of its manifestations -whether it is gender, against older adults or people with different capacities or against girls, boys and adolescents- and presents protective formulas against these situations.

Yamila González Ferrer, vice president of the National Union of Jurists of Cuba (UNJC) and member of the drafting commission of this document, told Cubadebate that it maintains the spirit of the National Program for the Advancement of Women (PAM) and the Comprehensive Strategy Against Gender Violence, approved by the Council of Ministers . Above all, it clearly raises the possible consequences for those who carry out this type of aggression.

“This Code is not for the violent. If we talk about affections as the axis of family relationships, the document seeks to promote a harmonious way of solving conflicts ”, he said.

According to Álvarez Tabío, who is also a member of the drafting commission, his first achievement is to clearly identify the existence of the problem. “ In Law it is very important to name things: now we have identified gender violence in the family space, it already has a place in the draft Code. Everything that means physical, verbal, psychological, sexual, economic abuse, negligence and neglect, whether by direct or indirect action or omission, is recognized there. This allows us to take effective measures for the protection of the victims ”.

The regulations establish responsibilities and palpable consequences for those who attack others, in each of the defined institutions. In addition, it states that all matters regarding family violence must be of urgent judicial protection.

Among the protective formulas that it resorts to, it stands out that the legal obligation to provide food can cease when the obligee engages in violent behavior. “If I am the person legally obliged to provide food to another and that other has manifestations of violence in any of its expressions against me, that obligation cannot be maintained,” explained the UH professor.

Within couple relationships, respect and non-violence are explicitly recognized among the duties of the spouses or people together; and the possibility of separating the assets during the validity of the marriage is established when violent acts are present, systematically or not and according to their magnitude.

In addition, among the impediments to adopting, we have been punished for crimes related to gender violence. Exercising mistreatment also constitutes a limitation for the denial, suspension or modification of family communication regimes. ” You cannot promote communication, much less with children and adolescents, if the person in question is violent, ” Álvarez-Tabío insisted.

Related to this principle, the document identifies aggressiveness as a possible cause of deprivation of parental responsibility, even if it is not directly exercised against children.

“If a father or mother mistreats their partner and that exchange is witnessed by the children, it may be cause for the deprivation of parental responsibility. Similarly, the guardianship established in favor of a minor can be removed in cases of gender violence ”, he added.

Confronting violence, beyond the norm

Yamila González Ferrer. Photo: Roberto Garaicoa.

Although the project of the new Families Code recognizes the acts of violence present in that space and establishes a response to them, it is not enough to resolve them, Álvarez-Tabío said.

Yamila González Ferrer agrees. In her opinion, the legislative improvement in this matter should also cover areas such as family criminal law and civil, family and criminal proceedings, which would strengthen the spectrum of protection in situations of violence. “Similarly, ongoing and systematic awareness and training of legal professionals is essential to guarantee an interpretation and application of our legal norms from a gender perspective.”

It is clear, the Code will not come with a magic wand. It cannot solve by itself a phenomenon that, moreover, transcends legislative resources. “Although from the legal point of view we will be able to solve something when each normative body makes an express mention and foresees legal consequences in the face of these types of events, the battle goes much further,” said the UH professor.

To the actions from the Law must be added the confrontation from the social, educational and cultural aspects, among other perspectives. It is urgent to assume that violence in the family space is not a private matter, it is not an individual problem; rather, it affects us all as human beings, as a society.

“A lot of communication is necessary, talking with our sons and daughters so that they do not reproduce these behaviors, making them aware that they cannot remain undaunted in the face of abuse in any of its manifestations. It is also the work of teachers, doctors, of any professional who from within its scope, it can contribute ”, Álvarez-Tabío pointed out.

Ultimately, it is about articulating efforts so that violence does not continue to hurt inside homes. And on that path, luckily, the new Code can be a great ally.

By Paquita Armas Fonseca, a Cuban journalist specialized in cultural issues. She is a regular contributor to Cubadebate and other digital media such as La Jiribilla, CubaSi and the Cuban Television Portal. She was director of El Caimán Barbudo.

By Paquita Armas Fonseca, a Cuban journalist specialized in cultural issues. She is a regular contributor to Cubadebate and other digital media such as La Jiribilla, CubaSi and the Cuban Television Portal. She was director of El Caimán Barbudo.

You must be logged in to post a comment.