Books 15

Ernest Tate on Cuba

The pdf link below is chapter fifteen from volume one of Ernest Tate’s memoir, “Revolutionary Activism in the 1950s and 1960s”, published by Resistance Books, London. In this chapter, using archival sources, he describes in detail how a small group of Canadian revolutionary socialists in the Socialist Educational League, S.E.L., later to become the League for Socialist Action, L.S.A., of which he was a leader, organized in 1960 to defend the early Cuban Revolution against a right-wing propaganda offensive inspired by American imperialism, designed to quarantine it from the Canadian people. Their campaign in defense of Cuba, he writes, was one of the most successful of its kind in the English-speaking world.

REVIEW: Vicki Huddleston’s Cuba memoir

Comments by By Dr. Néstor García Iturbe Translated and edited for CubaNews The first commentary on this book refers to what is printed on the cover as it is announced as “a diplomat´s chronicle of America´s long struggle with Castrós Cuba”, which does not reflect the reality of what is presented in the book. Part 1 of the book recounts Vicki Huddleston’s stay at the State Department’s Office of Cuban Affairs from 1989 to 1993. In referring to this stage, the author failed to take into account 30 years of aggression by the United States against Cuba, including the beginning and strengthening of the economic blockade, the invasion by the Bay of Pigs, the Missile Crisis and the thousands of terrorist activities and sabotage that Cuba suffered during those thirty years. That’s actually an important part of “Americás long struggle with Castro´s Cuba.” The correct thing would have been for the cover to show that the chronicle to which reference is made only from 1989 onwards, since in the way it is written it seems to have been written to cover the whole period since the beginning of the Cuban Revolution. In the first chapter she gives us a sample of the alliance between the U.S. government with the worst of the Cuban exiles, mainly with the Cuban American National Foundation and the Brothers to the Rescue [BTTR]. It presents the latter as an almost philanthropic organization dedicated to rescuing rafters, when it repeatedly violated Cuban airspace to launch propaganda and explosive devices. The author herself reports that, as a State Department official, in some of these violations of Cuban airspace, she travelled as a passenger on one of the BTTR planes. This is an example of something that an U.S. government official is not supposed to do. In her book, Mrs. Huddleston tries to describe, according to her, the police regime in Cuba, especially organized by the State Security, which she says does not miss any movement of foreign diplomats. Assuming that the author was totally convinced of what she said, we could describe what she sees as naïve during Illinois Governor George Ryan’s visit to Cuba. She states that during his stay she prepared a meeting attended by various ambassadors, and several of the so-called “dissidents”. And that in order to be able to speak freely, at the end of the meal she offered in her home, she waited for the servants to leave the room where they were gathered to begin the testimonies and opinions of each of them. If Cuban security has such a broad and efficient control, how many microphones would there be in the premises selected by Mrs. Huddleston to hold the secret meeting? The interference in Cuba’s internal affairs is also recognized by the former ambassador, when in a meeting with Colin Powell, she told him how she carried out actions with dissident groups, private libraries and independent journalists, adding that if they had more resources they would do much more. What would be the attitude of the U.S. government if Cuba or another nation were to begin to foment opposition for the purpose of overthrowing the established regime? Is that the right attitude of a diplomat representing his country to another? The book, at least, gathers the maneuvers and activities carried out by the United States against Cuba in order to destroy the Cuban Revolution. A true compendium of illegalities, dirty maneuvers, violations of diplomatic law, conspiracies and interference by the United States in Cuba’s internal affairs. A better title for the book would have been “Our Crook in Havana”. June 6, 2018

Comentarios del Dr. Néstor García Iturbe El primer comentario sobre este libro se refiere a lo que tiene impreso en la cubierta pues se anuncia como “a diplomat´s chronicle of America´s long struggle with Castrós Cuba”, lo cual no refleja la realidad de lo que se expone en el libro. La parte 1 del mencionado libro relata la estancia de Vicki Huddleston en la oficina de Asuntos Cubanos del Departamento de Estado a partir de 1989 hasta 1993. Al referirse a esa etapa el autor ha dejado de tomar en consideración 30 años de agresiones de Estados Unidos hacia Cuba, lo que incluye el inicio y fortalecimiento del bloqueo económico, la invasión por Bahía de Cochinos, la Crisis de los Misiles y miles de actividades terroristas y sabotajes que durante esos treinta años Cuba sufrió. Esa es en realidad una parte importante de “Americás long struggle with Castro´s Cuba.” Lo correcto hubiera sido que en la cubierta apareciera que la crónica a la que se hace referencia e solamente a partir de 1989, pues en la forma en que está redactado parece que fuera durante todo el período desde el inicio de la Revolución Cubana. En el primer capítulo nos da una muestra de la alianza del gobierno estadounidense con lo peor del exilio cubano, principalmente con la Fundación Nacional Cubano Americana y con los Hermanos al Rescate mostrando estos últimos como una organización casi filantrópica dedicada rescatar balseros, cuando la misma en repetidas oportunidades violó el espacio aéreo cubano para lanzar propaganda y artefactos explosivos. La propia autora relata que siendo funcionaria del Departamento de Estado, en algunas de esas violaciones del espacio aéreo cubano viajó como pasajera en uno de los aviones. Una muestra de algo que supuestamente no debe hacer un funcionario oficial del gobierno estadounidense. En su libro la señora Huddleston trata de describir, según ella, el régimen policiaco en que se vive en Cuba especialmente organizado por la Seguridad del Estado, que según ella no le pierde movimiento alguno a los diplomáticos. Partiendo de que la autora estuviera totalmente convencida de lo que dice, pudiéramos calificar de ingenuo lo que describe durante la visita a Cuba del Gobernador George Ryan. Plantea que durante la estancia del mismo preparó una reunión a la que asistieron distintos embajadores, varios de los llamados “disidentes” y que para poder hablar libremente, al terminar la comida que ofreció en su casa, esperó a que los sirviente abandonaran la habitación donde estaban reunidos para comenzar los testimonios y opiniones de cada uno. ¿Si la seguridad cubana tiene un control tan amplio y eficiente, cuantos micrófonos habría en el local seleccionado por la señora HUDDLESTON para efectuar la reunión secreta? La injerencia en los asuntos internos de Cuba también es reconocida por la ex embajadora, cuando en una reunión con Collin Powell, le relataba como realizaba acciones con grupos disidentes, bibliotecas privadas y periodistas independientes, agregando que si tuvieran mas recursos harían mucho mas actividades. ¿Cuál sería la actitud del gobierno de Estados Unidos si Cuba u otra nación comenzara a fomentar la oposición con el propósito de derrocar el régimen establecido? ¿Es esa la actitud correcta de un diplomático que representa a su país ante otro? El libro, al menos, recoge las maniobras y actividades realizadas por Estados Unidos contra Cuba con el fin de destruir la Revolución Cubana. Un verdadero compendio de ilegalidades, maniobras sucias, violaciones a lo establecido en el Derecho Diplomático, conspiraciones e injerencia por parte de Estados Unidos en los asuntos internos de Cuba. El mejor titulo para el libro “Our crook in Havana. 6 de junio 2018

Our Woman in Havana by Vicki Huddleston

by Walter Lippmann.

Our Woman in Havana por Vicki Huddleston

A Unique and Special Experience in the World

A Unique and special experience in the world

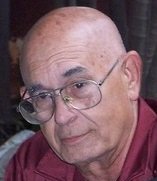

“From the Cuban strategy on sexual diversity, unique in the world, many countries, even developed, could learn,” says Canadian researcher Emily Kirk, author of the first foreign book on the official approach to this issue in the country.

By Mileyda Menéndez Dávila sentido@juventudrebelde.cu

and Jorge Sánchez digital@juventudrebelde.cu

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann.

Cuba’s gay Revolution: normalizing sexual diversity through a health-based approach is the first overseas vision of the Cuban Program to normalize sexual diversity based on health. Author: Juventud Rebelde Published: 09/02/2018 | 09:00 pm

From the Cuban sexual diversity strategy, unique in the world, many countries, even developed ones, could learn from it,” says Canadian researcher Emily Kirk, author of the first foreign book on the official approach to sexual diversity in the country.

Cuba’s Gay Revolution: normalizing sexual diversity through a health-based approach is the first overseas vision of the Cuban Program to normalize sexual diversity based on health. Author: Youth Rebel Published: 09/02/2018 | 09:00 pm

Although it is not among the books presented these days in La Cabaña, the debut of a text on Cuban reality is news in the international media.

This is the first vision from abroad of the Cuban program to normalize sexual diversity based on health: Cuba’s gay Revolution: normalizing sexual diversity through a health-based approach was published by Lexington Books, from the United States, after two years of persistent effort by its author, Canadian Emily Kirk, Doctor of Science in Latin American Studies and expert on global development issues.

She decided to first publish the results of her field research in the world’s most difficult publishing market, not so much because of the controversy over the sexual issue, but because of the suspicion that any scientific defense of the social achievements of revolutionary Cuba raises in that country.

This year, the book will be printed in the UK and Canada and presented in Spain. It has already been translated into Turkish and a Cuban publisher offered to take it to Spanish. Meanwhile, a copy of the work will be available at the Cenesex documentation center, courtesy of Kirk.

Beyond its publicized novelty as a first approach to the Cuban official vision on this issue, the text is a working tool for the multidisciplinary team that examines the implementation of the Millennium Development Goals in Brazil, Fiji, Ecuador, India, South Africa and Cuba.

As an international expert in health programs, she emphasizes the virtues of a strategy that is almost invisible to our population because of its daily obviousness. Her opinion is conclusive: the Cuban treatment of sexual diversity is a unique and very special experience in the world. Many countries, even developed ones, could learn from it to advance in the solution of problems that accumulate centuries of inequality.

You don’t have it all figured out, there is much to gain even in terms of laws, conduct, sexist stereotypes…But it is impressive how they have managed to focus their actions on the unquestionable value of human health, their physical and emotional well-being, beyond the subjective interpretation of what is a sexual right or how they exercised, which is the most frequent approach that other countries work with,” explained Dr. Kirk in an exclusive interview for Sexo Sentido.

Palpable evolution

The choice of the title of her work certainly reflects an advertising strategy, Emily said, smiling. The Cuban Revolution is well-known and attracts a lot of interest. Part of that admiration is due to the government’s obsession with the health of the people and its sincere efforts to bring that care to other parts of the world, he said.

She began her research on the Cuban health system in 2008, and from 2011 she focused on the systematization of treatment of sexual diversity. She has known the island since she was a child because he used to accompany her father, Dr. John Kirk, whose love for the history of Cuba she honors with this book today.

In the last ten years, she has been able to observe the country’s evolution regarding these issues, and she admires very much what has been achieved by Cenesex, the Federation of Cuban Women and other Cuban institutions, but above all, the change of mentality that is already being felt in the street.

It also believes that we have great advantages over other countries in the area in terms of laws in favor of the family and individual rights. It states that our society is prepared to update its codes in terms of what is popularly incorporated as knowledge, feeling and social behavior.

He enthusiastically asserts that her studies of Creole reality do not end here. The book is a balance between 1959 and 2014, but Cuba continues to evolve and she is eager to observe this process and share her achievements with other nations where her academic tasks and her humanist vocation also take her.

In all countries, this is a problem to be addressed. In my city, diversity marches began 25 years ago and the first time around 100 people participated (including my family); however, in 2016,100,000 people marched, a quarter of the entire population “.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator

Intro to Leon Trotsky mini-bio

New

New

Leon Trotsky

Compiled by ARIEL DACAL DÍAZ

2015 | Rebel Lives Collection |

“The name of Leon Trotsky is among the most controversial and irreplaceable figures in the history of the revolutionary movement.” -Ariel Dacal Díaz

Leon Trotsky has not lost, after death, the ability to arouse conflicting passions. His life and work attest to the tireless fighting spirit that always encouraged him, as well as his dedication to the revolutionary cause, founded on a sentiment that would never be able to abandon him: hope in the triumph of the oppressed.

Little more than seventy years have elapsed since his assassination, and yet the thought of Trotsky and the example of tenacity that constitutes his life still have much to say.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ariel Dacal Díaz

REBEL LIVES COLLECTION

Vidas Rebeldes, a new series of books at affordable prices that rediscover relevant figures in the history of the world’s workers, socialist and feminist movements. It publishes essay selections about women and men whose thought and action acquire renewed validity in our days. Vidas Rebeldes does not pretend to ennoble its protagonists as perfect political models, but to make them known in their different ways to the new generations.

168 pages | ISBN 978-1-925019-72-8

Intro to Ocean Sur Trotsky anthology

Introduction to Selected Texts by Leon Trotsky

New Leon Trotsky

Selected texts

Compiled by FERNANDO ROJAS

2015 | Marxist Library Collection |

The present selection has the first purpose of spreading the political ideology of Leon Trotsky, author of a considerably vast work and unavoidable personality of the history of the 20th century. Gathered in this volume, you can find some of his most significant and lucid writings.

An examination of the strategic and controversial debates originated in the heart of the revolutionary movement in the last century has to consider, by force, the figure of Trotsky. The chosen exts that Ocean Sur offers to the readers provide a valuable opportunity to revisit, or discover for the first time, the thought of this tireless theoretician and revolutionary, at the same time that they constitute an invitation to deepen, question and reflect.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Leon Trotsky

He was a Russian politician and revolutionary of Jewish origin, and one of the key organizers of the October Revolution, which allowed the Bolsheviks to take power in November 1917 in Russia. During the ensuing civil war, he served as commissar of military affairs.

Fernando Rojas

MARXIST LIBRARY COLLECTION

This collection brings together publications that address the origins, history and validity of Marxist thought.

472 pages | ISBN 978-1-921438-89-9

Translation by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Intro to Leon Trotsky: Selected Writings

- English

- Español

Leon Trotsky: Selected Writings (Introduction)

Selección, introducción y epílogo de Fernando Rojas

Índice Nota a la edición

1 About the compiler

2 Introduction

3 Fernando Rojas Chronology

17 Results and perspectives

23 1. The particularities of historical development

23 2. City and capital

30 3 1789 1848 1905

36 4. Revolution and proletariat

45 5. The proletariat in power and the peasantry

51 6. The proletarian regime

55 7. The preconditions of socialism

61 8. Labor Government in Russia and Socialism

77 9. Europe and the Revolution

82 Appendix.

Preface (1919) 90 Three conceptions of the Russian Revolution

97 The Bolsheviks and Lenin

117 Theses on industry

1. The general role of industry in the socialist structure

144 2. Assets and liabilities in the first period of the New Economic Policy

147 3. Problems and methods of planned industrial activity

4. Trusts, their role and the necessary reorganization

152 5. Industry and trade

154 6. The factory

155 7. Calculation, balance and control

156 8. Wages

157 9. Finance, credit and tariffs

158 10. Foreign capital

160 11. Plant managers, their position and their problems; the education of a new generation of technicians and managers

160 12. Party institutions and economic institutions

162 13. The Printing Industry 164 Address at the XIII Party Congress

165 Danger of bureaucratization

166 The generational problem

170 Fractions and groupings

172 Plan issues

174 About mistakes

179 Address to the XV Conference

And now? (Fragment)

219 Introduction

I. Social Democracy

224 II. Democracy and Fascism

230 III. The bureaucratic ultimatismo

238 IV. The Zigzags of the Stalinists on the Single Front

246 VIII. For the united front to the Soviets like supreme organ of the united front

256 X. Centrism “in general” and centrism in the Stalinist bureaucracy

262 XI. The contradiction between the economic successes of the USSR and the bureaucratization of the regime

271 XII. The Brandlerians (KPDO) and the Stalinist bureaucracy

278 XIII. The strategy of strikes

287 XIV. Workers’ control and collaboration with the USSR

296 XV. Is the situation desperate?

304 Conclusions

Economic development and leadership zigzags, “war communism”, the “New Economic Policy” (NEP), and the orientation towards the well-off peasantry

315 Turnaround: “the five-year plan in 4 years” and complete collectivization

323 Socialism and the State

333 The transition regime

333 Program and reality

336 The double character of the Soviet state

338 Gendarme and socialized destitution

341 “The Complete Victory of Socialism” and “The Consolidation of the Dictatorship”

344 The increase of inequality and social antagonisms

348 Misery, luxury, speculation

348 The differentiation of the proletariat

354 Social Contradictions of the Collectivized Village

358 Social physiognomy of the ruling circles

362 What is the USSR?

369 Social relations

369 State Capitalism?

Is the bureaucracy a ruling class?

379 The problem of the social character of the USSR is not yet solved by history

382 The USSR at War (Fragment)

385 The German-Soviet Pact and the Character of the USSR

385 Is it a cancer or a new organ?

386 The early degeneration of bureaucracy

387 The conditions for the omnipotence and fall of the bureaucracy

What will happen if the socialist revolution does not take place?

388 The present war and the fate of modern society

389 The theory of “bureaucratic collectivism”

390 The proletariat and its leaders

392 Totalitarian dictatorships, as a consequence of an acute crisis, and not of stable regimes

394 The orientation towards world revolution and the regeneration of the USSR

395 Foreign policy is the continuation of domestic policy

396 The defense of the USSR and the class struggle

397 Introduction

English Article Goes Here

León Trotski Textos escogidos

Selección, introducción y epílogo de Fernando Rojas

Índice Nota a la edición

1 Sobre el compilador

2 Introducción

3 Fernando Rojas Cronología

17 Resultados y perspectivas

23 1. Las particularidades del desarrollo histórico

23 2. Ciudad y capital

30 3. 1789‑1848‑1905

36 4. Revolución y proletariado

45 5. El proletariado en el poder y el campesinado

51 6. El régimen proletario

55 7. Las condiciones previas del socialismo

61 8. El Gobierno obrero en Rusia y el socialismo

77 9. Europa y la revolución

82 Apéndice.

Prefacio (1919) 90 Tres concepciones de la Revolución Rusa

97 Los bolcheviques y Lenin

117 Tesis sobre la industria

144 1. El rol general de la industria en la estructura socialista

144 2. El activo y el pasivo en el primer período de la Nueva Política Económica

147 3. Los problemas y los métodos de la actividad industrial planificada

148 4. Los trusts, su papel y la necesaria reorganización

152 5. La industria y el comercio

154 6. La fábrica

155 7. El cálculo, el balance y el control

156 8. Los salarios

157 9. Las finanzas, el crédito y los aranceles

158 10. El capital extranjero

160 11. Los gerentes de planta, su posición y sus problemas; la educación de una nueva generación de técnicos y de gerentes

160 12. Las instituciones del partido y las instituciones económicas

162 13. La industria gráfica 164 Discurso en el XIII Congreso del Partido

165 Peligro de burocratización

166 El problema generacional

170 Fracciones y agrupaciones

172 Cuestiones del plan

174 Acerca de los errores

179 Discurso a la XV Conferencia

183 ¿Y ahora? (Fragmento)

219 Introducción

219 I. La socialdemocracia

224 II. Democracia y fascismo

230 III. El ultimatismo burocrático

238 IV. Los zigzags de los estalinistas en la cuestión del frente único

246 VIII. Por el frente único a los sóviets como órgano supremo del frente único

256 X. El centrismo «en general» y el centrismo en la burocracia estalinista

262 XI. La contradicción entre los éxitos económicos de la URSS y la burocratización del régimen

271 XII. Los brandlerianos (KPDO) y la burocracia estalinista

278 XIII. La estrategia de las huelgas

287 XIV. El control obrero y la colaboración con la URSS

296 XV. La situación, ¿es desesperada?

304 Conclusiones

311 El desarrollo económico y los zigzags de la dirección, el «comunismo de guerra», la «Nueva Política Económica» (NEP) y la orientación hacia el campesinado acomodado

315 Viraje brusco: «el plan quinquenal en 4 años» y la colectivización completa

323 El socialismo y el Estado

333 El régimen de transición

333 Programa y realidad

336 El doble carácter del Estado soviético

338 Gendarme e indigencia socializada

341 «La victoria completa del socialismo» y «la consolidación de la dictadura»

344 El aumento de la desigualdad y de los antagonismos sociales

348 Miseria, lujo, especulación

348 La diferenciación del proletariado

354 Contradicciones sociales de la aldea colectivizada

358 Fisonomía social de los medios dirigentes

362 ¿Qué es la URSS?

369 Relaciones sociales

369 ¿Capitalismo de Estado?

377 ¿Es la burocracia una clase dirigente?

379 El problema del carácter social de la URSS aún no está resuelto por la historia

382 La URSS en guerra (Fragmento)

385 El pacto germano-soviético y el carácter de la URSS

385 ¿Se trata de un cáncer o de un nuevo órgano?

386 La temprana degeneración de la burocracia

387 Las condiciones para la omnipotencia y caída de la burocracia

387 ¿Y qué pasará si no tiene lugar la revolución socialista?

388 La guerra actual y el destino de la sociedad moderna

389 La teoría del «colectivismo burocrático»

390 El proletariado y sus dirigentes

392 Las dictaduras totalitarias, consecuencia de una crisis aguda, y no de regímenes estables

394 La orientación hacia la revolución mundial y la regeneración de la URSS

395 La política exterior es la continuación de la política interna

396 La defensa de la URSS y la lucha de clases

397 Introducción

A Alejandro II, el zar que abolió la servidumbre en 1861, los rusos le llamaban «el libertador». A Alejandro III, quien sucediera en 1881 al anterior, víctima de la organización revolucionaria terrorista «la voluntad del pueblo», le decían «el pacificador».1 Nicolás II, que ascendió al trono en 1896, no pudo ostentar ningún mote. Reinaba poco más de un lustro cuando declaró una guerra a Japón que costó a los rusos miles de muertos y la humillación nacional más grande desde la guerra de Crimea.2

Devastado por la contienda y sumido en una crisis que el fin de la servidumbre no había podido resolver, el país se agitaba, sacudido por las luchas obreras que conducía el mejor organizado de los partidos socialdemócratas de la época, a pesar de su escisión en dos tendencias: menchevique y bolchevique.

La escasez, la subida de precios y un crudísimo invierno justificaron la procesión pacífica de miles de habitantes de San Petersburgo el 9 (22) de enero de 1905. Iban a pedirle mejoras al padrecito zar. La historiografía soviética afirmó siempre que un provocador era el responsable de haber movilizado a la población de la capital rusa en circunstancias de altísima tensión social y política. Con independencia del crédito que merezca esta aseveración, la inconformidad iba a desatarse de cualquier modo.

El zar ordenó disparar sobre la manifestación.

Sucedió lo inevitable: la crisis nacional estalló en una revolución. En menos de un año los obreros organizaron los sóviets, los principales dirigentes del partido regresaron al país, surgieron las milicias armadas y se produjo la insurrección en Moscú. El movimiento evolucionó desde la agitación general a las manifestaciones obreras aisladas con determinado nivel de organización, de ahí a la huelga general y de esta a la insurrección moscovita de diciembre de 1905. En apretado cuadro pudo apreciarse el desarrollo político de los obreros y sus líderes, y también sus debilidades organizativas. Una adecuada expresión del panorama político en el campo revolucionario fue la elección de León Trotski, cuya posición pretendía ser equidistante de las dos fracciones socialistas principales, como presidente del sóviet de San Petersburgo.

La guerra campesina y la lucha de los pueblos oprimidos por el zarismo necesitaron seis meses más para abarcar el inmenso país y los obreros no pudieron sincronizar sus acciones con el movimiento rural.

La sangre de los obreros de Moscú, las promesas del zar y la reforma económica del ministro Stolipin consumieron a la revolución ya en los primeros meses de 1907.

El «ensayo general de la Revolución de Octubre» dejó a los rusos la extraordinaria experiencia del sóviet como organización de poder, reveló la crisis definitiva del régimen zarista, expresó las contradicciones del capitalismo en Rusia en su compleja interconexión con antiquísimas reminiscencias feudales y aproximó temporalmente a las dos fracciones socialdemócratas, que en el propio 1905 celebraron su congreso de unificación. No debe escapar al lector este último hecho cuando indague en la polémica de Lenin con los mencheviques. En 1905 —y hasta 1912— las fracciones del POSDR se consideraban integrantes de un único partido.

En el año 1905, la fuente del cambio era una gigantesca crisis nacional en todos los órdenes de la vida social. Ninguna clase, grupo o estamento podía continuar soportando el estado de cosas. La gran masa de la población quería vivir de otra manera, supuesta en las mentalidades grupales como mejor. No importaba el planteamiento estratégico o táctico de las fracciones políticas más que el elemental deseo colectivo de una transformación radical, que se imaginaba tan colosal como ambigua.

La hegemonía proletaria, además de una necesidad estratégica, fue una evidencia. Ninguna clase fue más consecuente.

Doce años de la más oscura reacción no pudieron evitar la bancarrota definitiva del zarismo.

Introducción

1905 en el marxismo

Para la fecha de la Revolución Rusa un importante sector de la socialdemocracia internacional había abjurado de la idea misma de la revolución. En Rusia los mencheviques concebían el movimiento, en el mejor de los casos, solo como una revolución burguesa. Ni ellos ni los más audaces de sus correligionarios en Europa otorgaban a Rusia la posibilidad de hacer alguna vez, o por lo menos en un período histórico breve, una revolución socialista. Los bolcheviques se oponían a este último extremo, pero coincidían en la idea de que la revolución que se iniciaba era esencialmente antifeudal. Bolcheviques y mencheviques concordaban en la idea de una revolución nacional que fortalecería las relaciones de producción capitalistas.

Lenin aportó en ese momento una idea capital para todo el desarrollo posterior del marxismo. Como ya se había esbozado en 1848 y, sobre todo, como se demostró en los procesos históricos que desembocaron en la formación de los Estados nacionales en Alemania e Italia, las burguesías nacionales no estaban ya dispuestas no solo a encabezar, sino ni siquiera a participar apenas en las transformaciones antifeudales. La contradictoria coexistencia de rasgos feudales y capitalistas en el entramado socioeconómico de Rusia y Europa oriental, desde fines del siglo xix, echaba a las burguesías en brazos de las más reaccionarias monarquías, por temor a la consecuente escalada de las revoluciones hacia transformaciones de corte socialista. De esta tendencia verificada y verificable surgieron la teoría de la revolución permanente de Trotski y la prefiguración leninista de la posibilidad de la revolución mundial desde el llamado «tercer mundo», que cristalizara definitivamente como postulado teórico en 1923.

La aparente equidistancia de Trotski de bolcheviques y mencheviques significa aproximarse a los primeros en cuanto al hecho de producir y aun encabezar la revolución misma, y a los segundos —lo cual a los ojos de este autor resulta decisivo— en cuanto a la imposibilidad absoluta de la revolución socialista en los marcos nacionales.

En cuanto a la revolución permanente casi es suficiente distinguir entre las dos aproximaciones de Marx al término que Trotski utilizara indistintamente, sin que ello implique tacharlo de manipulador: sencillamente, este último abordó el asunto en circunstancias reales y teóricas mucho menos «puras» que las que Marx analizó. Se trataba, por un lado, de la idea del triunfo de la revolución al mismo tiempo en los países «más avanzados» de la Europa Occidental y, por otro, de la idea del tránsito de la revolución por fases sucesivas hasta el comunismo, sin otra interrupción que no fuera la sucesión inmediata de clases, grupos sociales o partidos en el poder político nacional. En 1905 Trotski se refería esencialmente a esta segunda versión de la revolución permanente, restringiéndola a su visión táctica del desarrollo de la Revolución Rusa y subrayando su inevitable integración con la revolución en Europa.

Toda vez que Rusia no podía por sí sola ni hacer la revolución burguesa —porque la burguesía no la quería—, ni la socialista, el proletariado tendría que tomar el poder de inmediato, resolver las tareas pendientes de la burguesía, y solo se mantendría en el poder con el concurso de la revolución proletaria en Occidente.

En cualquier caso, el creativo apego del presidente del primer sóviet de Petrogrado —que lo fue también del que tomó el poder en 1917— a la ortodoxia marxista hacía su posición mucho más comprensible y menos contradictoria en las mentes de los ideólogos contemporáneos3 que la más sutil, compleja y —en la distancia— audaz posición de Lenin, que parecía insostenible a los ojos de la mayoría de los marxistas de la época, empezando por Trotski, con independencia de que se situaran a la izquierda o a la derecha del canon socialdemócrata (menchevique, si se trata de Rusia) imperante.

En la polémica, Lenin carga las tintas sobre los mencheviques y, en tanto Trotski pertenecía anteriormente a esa corriente, Lenin asume como hecho incontrovertible la militancia de este en la posición de aquellos. Solo menciona dos veces y de pasada a su antiguo discípulo, próximo oponente y futuro correligionario. La posición de Trotski era, en efecto, muy minoritaria dentro del partido. El mantenerse, por lo menos en apariencia, fuera del debate de las dos grandes fracciones fue probablemente lo que dio a Trotski más amplio predicamento entre sectores de masas del proletariado de San Petersburgo. El asunto era mucho más complicado, salpicado del carácter muy polémico de las argumentaciones y no desprovisto de ciertas dosis de escolástica,4 las que resultaron letales para el Partido bolchevique, a largo plazo, en la dinámica de sus discusiones internas.

Al convertirse en el líder de la fracción bolchevique, Lenin no albergaba la menor duda acerca de la concomitancia decisiva de dos magnitudes sociológicas aparentemente —a los ojos de la escolástica «tradición» marxista—5 muy contradictorias: la transformación anticapitalista de la Rusia zarista, o la lucha contra el capitalismo ruso, si se prefiere, transcurriría de la mano de una revolución campesina antifeudal, y ambos serían dos procesos en uno. Este autor pone particular énfasis en el término anticapitalista, pues es esta la clave de la ambigüedad (según Trotski) de la fórmula táctica leninista de 1905.6

Polemizando, quizás sin saberlo, con la versión trotskista de la revolución permanente, 7 Lenin distingue el Gobierno revolucionario que propone de la «conquista del poder», entendiendo esta última como la conquista del poder por el proletariado para establecer su dictadura y el consecuente tránsito al socialismo.

Es importante llamar la atención sobre el hecho de que tanto Trotski como Lenin, a diferencia del grueso de los líderes mencheviques, eran insurreccionales ya en 1905. En la discusión, sin duda, Trotski resulta mucho más cautivo de la escolástica, si bien más comprensible a la luz pública,8 al embrollarse discutiendo con Lenin sobre el objetivo final. Este último ya ha dejado claro que el objetivo final no está en la discusión, sino que sencillamente aún no está a la orden del día. No es difícil aventurar que la tan cacareada y manipulada revolución permanente es hija de estas divergencias.

Y sin embargo, Lenin insiste en el carácter proletario, en determinado sentido, de la Revolución:

La peculiaridad de la Revolución Rusa estriba precisamente en que, por su contenido social, fue una revolución democrático-burguesa, mientras que, por sus medios de lucha, fue una revolución proletaria. Fue democráticoburguesa, puesto que el objetivo inmediato que se proponía, y que podía alcanzar directamente con sus propias fuerzas, era la república democrá tica, la jornada de ocho horas y la confiscación de los inmensos latifundios de la nobleza: medidas todas ellas que la revolución burguesa de Francia llevó casi plenamente a cabo en 1792 y 1793.9

El año 1917 pareció demostrar que la diferencia táctica entre Lenin y Trotski significaba muy poco. A la larga Trotski demostró que tampoco suponía que en Rusia estuvieran maduras las condiciones para el socialismo, no ya en 1905, sino ni siquiera en 1925. Sin embargo, Trotski, como Stalin10 años más tarde desde el extremo opuesto, propendía a plantearse el problema desde visiones teóricas generalizadoras y metas a alcanzar, más que desde el análisis concreto de la situación rusa, que era el fuerte de Lenin. Este último, por tanto, atacó duramente a los mencheviques, no tanto por las diferencias tácticas como por sus consecuencias estratégicas —sobre todo por la actitud ante la burguesía— tendientes a hacer prácticamente nula en cualquier perspectiva, una revolución socialista. Lo dominante en el menchevismo de 1905, más que la traición abierta —lo que sucedió en 1914 con la mayor parte de la fracción—, es la inconsecuencia.

Hay un aspecto más sutil en la crítica antimenchevique, que se pierde en los avatares de lo psicológico y en los misterios de las mentalidades colectivas, específicamente dentro de las vanguardias políticas: en 1789 el común de los franceses, políticamente activos o no, identificaba la crisis nacional con la crisis del modelo; en la Rusia de 1905 ya no era tan así. En la misma medida en que la burguesía se desplazó, por su temor a las masas, de una posición antifeudal militante a una posición de connivencia con sectores de la oligarquía, determinados segmentos de los que ostentaban la representación popular retrocedieron igualmente hacia la connivencia con la burguesía.

El asunto adquiría mayor importancia en tanto el despertar de la actividad política de la gran masa de la población tenía lugar al calor de una revolución que, desde sus bases, trascendía las meras transformaciones antifeudales. Hoy se nos escapa con frecuencia que buena parte de las tan cacareadas libertades burguesas se conquistó por las masas luchando contra la burguesía. El sufragio universal es el mejor ejemplo. Engels vio en él, al final de su vida, una excelente arma de lucha por el poder en manos del proletariado. La Revolución de 1905 se produce varias décadas antes de que los centros ideológicos del capitalismo comenzaran a manipular esas ideas en su provecho, aunque nunca las hubieran llevado consecuentemente a la práctica.

Había que convencer de la necesidad de hacer una revolución realista, comprensible y beneficiosa, garantizando a cualquier plazo el tránsito al socialismo.

Un abarcador resumen de las diferencias dentro de la socialdemocracia rusa es ofrecido por Trotski mucho después:

En resumen. El populismo, como el eslavofilismo, provenía de ilusiones de que el curso de desarrollo de Rusia habría de ser algo único, fuera del capitalismo y de la república burguesa. El marxismo de Plejánov se concentró en probar la identidad de principios del curso histórico de Rusia con el de Occidente. El programa que se derivó de eso no tuvo en cuenta las peculiaridades verdaderamente reales y nada místicas de la estructura social y el desarrollo revolucionario de Rusia.

La idea menchevique de la Revolución, despojada de sus episódicas estratificaciones y desviaciones individuales, equivalía a lo siguiente: la victoria de la revolución burguesa en Rusia solo era posible bajo la dirección de la burguesía liberal y debe dar a esta el poder. Después, el régimen democrático elevaría al proletariado ruso, con éxito mucho mayor que hasta entonces, al nivel de sus hermanos mayores occidentales, por el camino de la lucha hacia el socialismo.

La perspectiva de Lenin puede expresarse brevemente por las siguientes palabras: La atrasada burguesía rusa es incapaz de realizar su propia revolución. La victoria completa de la revolución por medio de la «dictadura democrática del proletariado y los campesinos», desterraría del país el medievalismo, imprimiría al capitalismo ruso el ritmo del americano, fortalecería el proletariado en la ciudad y en el campo, y haría posible efectivamente la lucha por el socialismo. En cambio, el triunfo de la Revolución Rusa daría enorme impulso a la revolución socialista en el Oeste, y esta no solo protegería a Rusia contra los riesgos de la restauración, sino que permitiría al proletariado ruso ir a la conquista del poder en un período histórico relativamente breve.

La perspectiva de la revolución permanente puede resumirse así: la victoria completa de la revolución democrática en Rusia solo se concibe en forma de dictadura del proletariado, secundado por los campesinos. La dictadura del proletariado, que inevitablemente pondría sobre la mesa no solo tareas democráticas, sino también socialistas, daría al mismo tiempo un impulso vigoroso a la revolución socialista internacional. Solo la victoria del proletariado de Occidente podría proteger a Rusia de la restauración burguesa, dándole la seguridad de completar la implantación del socialismo.11

Sin embargo, el esbozo de la posibilidad de una revolución socialista en Rusia y, aun más, en el mundo subdesarrollado, tendrían que aportar una 10 León Trotski: Textos escogidos corrección al esquema de Marx que trascendería, con mucho, la recuperación, recreación y superación de lo mejor de la herencia revolucionaria burguesa, de la que los bolcheviques se enorgullecían, y del marxismo conocido. Sucedió que la globalización y el progreso científico-técnico que Marx concibió imposibles en la sociedad capitalista que le tocó vivir, continuaron su paso indetenible de la mano del capitalismo, expresando de manera cada vez más contradictoria el carácter social de la producción y ya no solo el carácter individual de la apropiación, sino de cualquier tipo de consumo, incluida la apropiación de la cultura.

1905, 1917… y 2008

Lenin no se planteó nunca la historia en términos de teleología. Era demasiado revolucionariamente irreverente para eso. La continuidad de 1905 en 1917 está tajantemente definida, pero las diferencias eran sustanciales. La expresión de Trotski de que en 1917 «los bolcheviques se desbolchevizaron»,12 que fue su explicación de la alianza con Lenin en vísperas del movimiento de octubre, se interpretaba en las discusiones de los años veinte desde un escolasticismo irreparable, contrastante con el altísimo nivel intelectual del bolchevismo en tiempos de Lenin. La idea de Trotski era que los bolcheviques habían defendido siempre la sucesión de etapas en la revolución, contra la revolución permanente y el argumento principal a su favor eran las tesis de 1905. En 1917, siguiendo el testimonio de Trotski, los bolcheviques renunciaron a su postura anterior y se encontraron con la posición de este último.13 Los sucesivos adversarios de Trotski14 en la década del veinte argumentaban que eso no era cierto, que la «dictadura revolucionaria de los obreros y los campesinos» contenía en su germen todo lo necesario para el tránsito a la revolución socialista, que Lenin enfatizó en la hegemonía proletaria en la revolución democrática —lo que es cierto, pero no es el punto—, que el partido conduciría sucesivamente a la clase obrera en todas las etapas15 de la revolución, etcétera.

En realidad y según consta en las fuentes primarias, sencillamente habían cambiado las condiciones: «Señalaremos de pasada que esos dos defectos [se refiere a los “defectos” de las condiciones de la revolución en 1905, F.R.] serán eliminados indefectiblemente, aunque tal vez más despacio de lo que Introducción 11 nosotros deseáramos, no solo por el desarrollo general del capitalismo, sino también por la guerra actual […]».16

Aparte de la eliminación de los defectos, sucedió que en febrero de 1917 la burguesía, contra todos los pronósticos anteriores de Lenin y Trotski,17 sí tomó el poder, ciertamente en singular convivencia con el poder de los sóviets.

Lo que la Revolución de 1905 no logró aportar al desarrollo de un capitalismo avanzado sería suplido con creces, por el inevitable desarrollo del propio capitalismo ruso y, sobre todo, por la guerra mundial. Esta conclusión tiene particular importancia en lo que se refiere a la educación de la clase obrera rusa y de su partido.

Lamentablemente, ese singular aspecto de la herencia de Lenin ha permanecido en el olvido. Múltiples y contradictorias tendrían que ser las consecuencias de tal planteamiento. El espacio solo permite algunos apuntes.

Para empezar, sería muy sugerente una lectura hacia atrás del tercer tomo de El capital, una aproximación contemporánea a las esencias de la reproducción ampliada, contenida exhaustivamente en muchos estudios, poco conocidos y censurados por la maquinaria ideológica del capitalismo, acerca del injusto orden económico mundial de nuestros días.

Marx y Engels analizaron la reproducción ampliada tomando en cuenta las relaciones de intercambio entre los centros del capitalismo. Las colonias se veían como una prolongación de las metrópolis, en una perspectiva que no se diferenciaba mucho de una relación de intercambio precapitalista. Por ello, el análisis de la dominación económica y de la formación de la plusvalía prácticamente se circunscribía a la relación entre los patronos y los obreros. Estos últimos, al emanciparse, emanciparían al resto de la población oprimida incluyendo a los habitantes de la periferia del capitalismo.

Los bolcheviques se quedaron solos con su revolución en un país devastado. Estaban obligados a crear las premisas materiales del socialismo que, según Marx y Engels, debieron madurar en el capitalismo, y ya no podían contar con la solidaridad del proletariado europeo triunfante como contrapeso a la insuficiencia del capitalismo ruso. Más que la ley del valor,18 es esta circunstancia, imprevisible para Marx, la que rige, ineluctablemente, el proceso de construcción del socialismo históricamente conocido. En ella hay que buscar los fundamentos de los audaces planteamientos acerca de las «tareas inmediatas del poder soviético», la NEP, el plan cooperativo y hasta la teoría de Bujarin sobre la «construcción del socialismo a paso de tortuga, tirando de nuestra gran carreta campesina».19

La guerra y la reacción habían demostrado con creces que no se vencería al capitalismo mediante el sufragio universal, que la socialdemocracia internacional, en el mejor de los casos, no podía aceptar el aserto anterior y en el otro extremo, sencillamente comenzaba ya a representar a los sectores medios beneficiados por la opresión colonial y de las capas más pobres de las sociedades de los países capitalistas desarrollados. La explotación de los inmigrantes en todo el mundo capitalista desarrollado contemporáneo es una singular expresión de ese fenómeno.

En la misma medida en que no era posible plantearse que la sola maduración de las condiciones del socialismo en el marco del capitalismo avanzado desembocara en la revolución que lo barriera, tampoco podía contarse ya con que la premisa de la democracia burguesa fuera suficiente para la construcción del orden político socialista. Después de destacar en El Estado y la revolución la cuestión de principio del derribo de la maquinaria estatal burguesa, pone en los sóviets la atención que no había fijado en 1905, insistiendo sobre todo, además de las elecciones, en las cuestiones de la dirección colectiva, la participación y la revocación. Eran estas últimas las que distinguirían definitivamente la nueva maquinaria estatal de la anterior, las que prefiguraban desde su fundación la inevitable desaparición de cualquier maquinaria, condición indispensable al nuevo Estado que parecía iba a durar un tanto más de lo previsto.

La convivencia más o menos larga del país socialista aislado con las grandes potencias capitalistas imponía la necesidad de una geopolítica de Estado a la Rusia soviética. No era este el ideal de Marx y Engels. Lenin pretendió resolver la contradicción haciendo públicas todas las políticas y ampliando a todo cauce la discusión ideológica.

En poco tiempo los sóviets se burocratizaron y la geopolítica impuso limitaciones al ejercicio democrático. Más que eso, el país soviético tuvo que dirimir el conflicto inevitable con el capitalismo por medio de las armas.

Lenin se respondió a sí mismo planteando el imperativo de una revolución cultural. Hacía mucho tiempo había manifestado la necesidad del cambio cultural, pero lo veía inmerso en la lógica del desarrollo del capitalismo, primero, y después, como algo concomitante a la revolución mundial. Tanta fue su insistencia que no han faltado quienes lo acusen de europeísta o eurocentrista, cuando en realidad no hacía más que ser fiel al espíritu de los tiempos, lo que es bastante pedir para un revolucionario. En este asunto y en el de la democracia vuelve a aparecer el problema de la identificación o la comprensión, al menos, de algunos valores de la burguesía,20 asunto que la división geopolítica y el estalinismo militante convirtieron en tabú. Por lo pronto, se trataba de producir en la Rusia atrasada una revolución cultural que no solo ni mucho menos igualara a la sociedad soviética con sus vecinos capitalistas, sino que los superara y planteara el problema del cambio cultural, desde una perspectiva completamente nueva, que amalgamara la tradición popular, asimilara lo mejor de la cultura universal y propusiera un modo de vida, una percepción ideológica y un arte nuevos, todo eso a un tiempo.

La combinación entre la lucha contra la burocracia, el plan cooperativo y el cambio cultural, debería conducir a una sociedad suficientemente próspera e igualitaria, con espacios de participación colectiva relativamente libres de la presión estatal, que funcionaran como un nuevo tipo de sociedad civil, encabezada por el partido, pero ejerciendo presión sobre su aparato. La vida espiritual sería —y tendría que ser— rica, amplia y diversa, medio de realización ciudadana y de enfrentamiento a cualquier forma de opresión, propia o ajena. En ese escenario, el primer Estado socialista podría intentar liderar una revolución de los pueblos oprimidos.

En definitiva, una vez vencidas las oposiciones bolcheviques de los años veinte, lo dominante en la política y la ideología soviéticas fue la preservación del poder del Estado y una mejoría temporal de las condiciones de vida del ciudadano común, ciertamente en términos de igualdad nunca vistos en la historia humana. Pero no pudieron crearse las condiciones materiales, culturales y políticas del socialismo que Marx vislumbró.

La socialización de la cultura y su extraordinaria, inagotable y definitiva concomitancia con el progreso científico quedaron en manos de la burguesía mundial, la que, consciente de que tenía que enfrentar una alternativa formidable, puso su baza en la pugna, iniciando la tradición burguesa —pronto cumplirá cien años— de políticas de Estado, eficaz arma ideológica contra el socialismo. El mundo de fines del siglo xx pudo contemplar, como la expresión más acabada de la dominación de muchos por unos pocos, el control del imperialismo sobre la difusión de la cultura. Tal contemplación es posible —dramática prueba de la monstruosidad del dominio— solo después de un arduo esclarecimiento.

El orden posterior a la Segunda Guerra Mundial se definió mucho más por las necesidades geopolíticas que por los intereses de los pueblos, aun cuando estos últimos fueron preservados en la medida en que no contradecían las condiciones que Stalin consideró imprescindibles para la supervivencia del Estado soviético deformado, que a pesar de todo seguía siendo una alternativa al sistema capitalista. El titánico esfuerzo de los hombres y mujeres soviéticos no alcanzó al medio siglo después de su supuesto cénit. Menos de dos décadas después, las angustias de Lenin aparecen con toda su crudeza: chinos y vietnamitas prueban la «economía socialista de mercado», tras el olvidado Bujarin, los incorregibles yugoslavos y el brillante pragmá tico Deng Xiao Ping, sin poder librarse de la amenaza de una restauración capitalista, tan espontánea y natural que no pueda ser evitada.

Una lectura cuidadosa de la herencia póstuma de Lenin indica a este autor que la imposibilidad de liberar a los ciudadanos de la coerción estatal y las obligaciones geopolíticas inevitables del país socialista aislado, además de la prioritaria construcción de los fundamentos materiales de un socialismo todavía lejano, condujeron a Lenin a esbozar, junto a la revolución tercermundista, una peculiar —e inédita en el marxismo— versión de la sociedad civil, el Estado y la relación entre ambos. Se trata de que, conservando en manos del Estado los pilares de la economía y los servicios (la energía, el transporte, la industria pesada y la cultura), las esencias de la dictadura proletaria y de sus órganos de poder; la sociedad civil, asentada materialmente —sobre todo— en la producción cooperativa21 y en condiciones de la más amplia democracia proletaria y la más abierta discusión ideológica, asumiera cada vez más funciones propias en la construcción del socialismo. La desburocratización del partido y la presencia en sus órganos de dirección a todos los niveles de obreros de filas, la oposición a la fundación de la URSS y la reforma del control, sustituyendo su esencia burocrática por un verdadero control popular, deben aquilatarse en el contexto de esta visión. El partido es percibido como líder de la sociedad civil, junto al Estado, pero sobre todo frente a él. No es ocioso apuntar que tal práctica permeó toda la actividad de Lenin en el período más fecundo de su labor como jefe del Gobierno bolchevique.

La dominación cultural del capitalismo contemporáneo otorga a la revolución tercermundista una dimensión más trascendente: al luchar por el socialismo, nuestros pueblos luchan también por la cultura, por la liberación espiritual del género humano.

Las esperanzas parecen volverse hacia los procesos que, sin mucho apego a las elucubraciones marxistas y leninistas, enfilan su rumbo, sencillamente, a transformar un orden que puede significar el fin de la civilización. Es tan atroz el capitalismo que después de derrotar al socialismo soviético y su extensa saga «en nombre de la libertad», parece encaminarse a hacer perecer al género humano.

Lenin lo previó casi todo, salvo la propensión de sus sucesores al crimen de lesa humanidad. Los procesos en ciernes le dan razón hasta la profundidad de los pasados cien años. Ello no resta méritos a los que han intentado, contra los crímenes de Stalin y las aventuras ultraizquierdistas, buscar caminos alternativos hacia el poder del pueblo, ni a los que han pretendido derivar de las culturas nacionales la solución a los problemas propios, como él mismo hizo, amén de desarrollar, heréticamente, lo mejor del marxismo. Pero nadie se ha hecho, como Lenin, las mismas preguntas sobre las perspectivas de la felicidad de pueblos enteros, desde la cúspide del poder del Estado más extenso, uno de los más poblados, más pobres y más pioneros que conoce la historia del género humano.

Hace poco leí que el cuerpo momificado de Lenin podría albergar células susceptibles de producir un clon. Presto a la noticia el poquísimo crédito que inspira el sensacionalismo de la prensa burguesa. No puedo evitar, sin embargo, sonreír ante la perspectiva de que nos encuentre discutiendo los mismos problemas que le atormentaron al morir. Por lo pronto, intente el lector indagar sobre esos problemas en la visión de la Revolución de 1905.

Fernando Rojas

La Habana, 5 de agosto de 2008.

Ernest Mandel and Cuba

Love and Revolution

Chapter 8 of Ernest Mandel, A Rebel’s Dream Deferred by Jan Willem Stutje, pp.147-164

“It is more pleasant and useful to go through the ‘experience of the revolution’ than to write about it.”

— V.I. Lenin, The State and Revolution 1

The progressive revival of the 1960s, which in Belgium began with the general strike of 1960-61, brought with it a renewal of the connection between struggle and theoretical debate, a connection that had been lost during the interwar ‘darkness at noon’ of Stalinism.

Although Marxist critical thought had not been entirely silenced, as shown by the works of Cornelius Castoriadis and Paul Sweeny, Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks and Karl Korsch’s later work, in academia it had been marginalized, confined to the domains of aesthetics and philosophy.2 In the 1960s such publishers as Maspero in France and Feltrinelli in Italy rediscovered the heterodox political literature that had long been on Stalin’s index. Creative Marxist thought emerged from the shadow of the universities and stimulated — in addition to the debates about neo-capitalism and the role of the proletariat — thinking about decolonization, revolution and post-capitalist society, the Soviet Union and China, Algeria and Cuba.

In Marxist Economic Theory Mandel had examined the economics of transitional societies.3 The sociologist Pierre Naville encouraged him to pursue the subject further. Naville was preparing to republish New Economics (first published in 1923), an analysis of the Soviet economy by Yevgeni Preobrazhensky, who had been killed by Stalin in 1937.4 He asked Mandel to write a foreword. 5 Central to the book was the question of what dynamic would arise in an agricultural society in transition from capitalism to socialism and what sources of socialist accumulation would be available. Mandel wrote that Preobrazhensky had made possible an economic policy free of pragmatism and empiricism.6 This book’s publication contributed to the economic debate in Cuba.

In Cuba with Che Guevara and Fidel Castro

Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, who with Fidel Castro was the face of the Cuban revolution, took a leading role in this debate. In 1958-59 guerillas had ended the oppressive, US-backed Batista regime. In doing so they broke with the prevailing, understanding of revolution that had held sway since 1935. The dominant conception dated back to the stages theory held by Stalin’s Comintern, which had limited revolutionary ambitions to formation of a national democratic government with the task of achieving agricultural reform, industrialization and democratic renewal. The struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie would only take place in a more-or-less distant future phase of socialist revolution. The Cuban revolutionaries discovered that in practice such a revolution was impossible and looked for a model that would put a definitive end to capitalism in Cuba. In the process they risked an American invasion, a threat made clear during the Bay of Pigs (Playa Giron) incident and the October 1961 missile crisis. They also earned anathemas from Moscow, which saw Cuba’s, support for revolutionary movements -in Latin America, Asia and Africa as undermining a foreign policy aimed at peaceful coexistence with the West.

From 1962 to 1964 Che Guevara headed the Cuban ministry of industry. He opposed the growing influence of Moscow-oriented Communists and the state’s increasing bureaucratic tendencies. His ideas about the economy were formed in the debates of 1963-4. which were not only about economic development but also about the essence of socialism: a central budget structure versus, financial independence of companies, moral versus material incentives, thee law of value versus planning, and the role of consciousness.

Che considered an economy without a humanistic perspective, without communist ethics, unthinkable.7 ‘We fight against poverty but also against alienation…If Communism were to bypass consciousness…then the spirit of the revolution would die.’8 In a famous 1965 essay, ‘Socialism and Man in Cuba’, Che warned against ‘the pipe dream that socialism can be achieved with the help of the dull instruments left to us by capitalism’, like making value and profitability the absolute economic’ measure or using, material incentives. Che held that fully realized communism would require changing not only the economic structure but also human beings. 9

Impressed by the wave of nationalizations there, Mandel concluded in the fall of 1960 that Cuba had developed into a post-capitalist state.10 ‘Reality has shown that to consolidate power the revolutionary leaders have unconsciously resorted to Trotskyism.’11 Shortly after the publication of Marxist Economic Theory Mandel had a copy sent to Che and Castro via their embassy in Brussels.12 He had informal contacts, with the Cuban regime through Nelson Zayas Pazos,13 a Cuban Trotskyist and French teacher working in the foreign ministry, and Hilde Gadea, Che’s ex-wife a Peruvian economist of Indian and Chinese descent who lived in Havana.14 Gadea was sympathetic to Trotskyist ideas, and through her and Zayas documents of the Fourth International were regularly forwarded to Che. 15

In October 1963 Zayas told Mandel about the debate raging between what he called the Stalino-Khrushchevists and the circle around Che.16 While the former were arguing for financial independence for companies and for material incentives to increase productivity,17 Che called for centralizing finances and strengthening moral incentives.18 Zayas encouraged Mandel to intervene in the debate: ‘It seems to me that the entire Castro leadership would welcome such a contribution … Fidel, Che, Aragonés. Hart, Faure Chomón and many others are favourably disposed to us.’19. A month later Zayas distributed a stencilled contribution from Mandel to those taking part in the debate. 20 Mandel supported Che’s resistance to financial autonomy, not because he was opposed to decentralization but because centralized financing for small-scale industry seemed at that time the optimal solution. He shared Che’s fears of the growth of bureaucracy, all the more so because Clue’s opponents wanted to make decentralized financial administration efficient by using material incentives. Mandel was not against material incentives as such, on two conditions: that they were not individual but collective incentives in order to ensure solidarity, and that their use was restrained in order to curb the selfishness that a system of enrichment produces.

To combat bureaucratization Mandel argued for democratic and centralized self-management, ‘a management by the workers at the workplace, subject to strict discipline on the part of a central authority that is directly chosen by workers’ councils’.21 Mandel and Che differed on this last point. Che did support management of the enterprises by the trade unions, but only if they were representative and not controlled by Communists, who, he said, were very unpopular. The results of decentralized self-management in Yugoslavia, where companies acted like slaves of the market, had also made Che cautious. Mandel warned him against throwing the baby out with the bath water. Self-management by workers was entirely compatible with a central plan democratically decided by the direct producers.22

In early 1964 Mandel was invited to visit Havana. There were prospects of meetings with Che and Castro.23 Che had read Marxist Economic Theory enthusiastically and had large parts of it translated.24 Mandel confided to Livio Maitan: ‘I think that I can raise many issues openly and frankly’,25 and wrote again a few days later, `And in any case I can resolve the question of banning our Bolivian friends.’26

Maitan had visited South America for the first time in 1962. He had made contact with insurrectionary movements in Bolivia, Chili, Peru, Venezuela, Uruguay and Argentina and had urged them to work with the Cubans.27 In Buenos Aires he met such left-wing Peronistas as the poet Alicia Eguren and her partner John William Cooke, who had been in contact with Che since 1959.28 In Peru Maitan’s contacts were with the United Left and its present leader Hugo Blanco. In Bolivia he met with the mine workers in Huanuni, Catavi and Siglo XX. Trotskyists had strong influence there and hoped to be trained in Cuba for armed struggle.

Mandel stayed in Havana for almost seven weeks. It was a visit without official duties, an occasion for exchanging ideas, and these exchanges convinced him completely that Cuba ‘constitutes . . the most advanced bastion in the liberation of labour and of humanity’.29 The Marxist classics were widely studied in cadre schools, in ministries and beyond. Mandel wrote a friend, ‘The class I took part in had just finished volume one of Capital, with a minister and three deputy ministers present . . . And it was serious study, even Talmudic, studying page by page…’30 Mandel’s own works, including Marxist Economic Theory, were discussed; translated, stenciled excerpts circulated among the leadership.31 Mandel wrote to his French publisher, ‘The president of the Republic [Osvaldo Dorticos] himself is interested in the work and would like to publish it in Spanish in 2 Cuba.’ E. Mandel to C. Bourgois, 28 May 1964, E. Mandel Archives, folder 278.] He addressed hundreds of auditors at the University of Havana, speaking in Spanish — with a sprinkling of Italian when a words escaped him. There was even an announcement of his visit in Hoy, the paper, of the Communist Blas Roca. Revolutión, the largest and most influential daily paper, published an interview.

‘I was literally kidnapped by the finance ministry and the ministry of industry [Che’s ministry] to write a long article about the problem of the law of value in the economy of a transitional society.’32 Speaking French, Mandel met for four hours with Che, who received him dressed in olive green fatigues, his famous black beret with its red star within reach. Totally enchanted, Mandel wrote a friend, ‘Confidentially, he is extremely close to your friend Germain [the pseudonym Mandel used most], whom, you know well.’33

Mandel and Che worked together on a response to the French economist Charles Bettelheim. In April 1964 Bettelheim had published an article in the monthly Cuba Socialista34 that held that the central planning that Che advocated was unwise policy, considering the limited development of the forces of production. The Marxist Bettelheim had become Che’s most profound critic. Other opponents included Alberto Mora, the minister of foreign trade, and Carlos Rafael Rodríguez, the minister of agriculture. Years later Bettelheim commented,

Cuba’s level of development meant that the various units of production needed a sufficient measure of autonomy, that they be integrated into the market so that they could buy and sell their products at prices reflecting the costs of production. I also found that the low level of productive forces required the principle: to each according to his work. The more one worked, the higher the pay. This was the core of our divergence, because Che found differences acceptable only when they arose from what each contributed to the best of his ability.35

The research director of the Paris Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales still did not agree with Che’s thinking.

Mandel thought that Bettelheim was making the mistake of looking for pure forms in historical reality. For example, according to the French economist, there could be no collective ownership of the means of production as long as legally there was no completely collective ownership. Mandel found Bettelheim’s insistence on such complete ownership- ‘to the last nail’ – a bit technocratic. Complete ownership was not necessary as long as their was possession sufficient to suspend capital’s laws of motion and initiate planned development.36 Mandel pointed out that the withering away of the commodity form was determined not only by the development of the forces of production but also by changes in human behaviour. It was a commonplace to say that the law of value also played a role in a post-capitalist economy without saying what part of the economy it would govern. The key question was whether or not the law of value determined investment in the socialist sector. If that was necessarily the case, Mandel said,then all underdeveloped countries – including all of the post-capitalist countries except Czechoslovakia and East Germany – were doomed to eternal underdevelopment. He pointed out that these counties agriculture was more profitable than industry, light and small-scale industry more profitable than heavy and large-scale industry, and above all obtaining industrial products on the world market more profitable than domestic manufacturing. ‘To permit investment to be governed by the law of value would actually be to preserve the imbalance of the economic structure handed down from capitalism.’37 With his criticism Mandel was not denying the law of value but opposing what he termed Bettelheim’s fatalism, which denied that a long and hard struggle was necessary ‘between the principle of conscious planning and the blind operation of the law of value’.38

Luis Alvarez Rom, Cuba’s finance minister, spent ten hours correcting the Spanish translation of Mandel’s article. It appeared in June 1964 under the title ‘Las categorías mercantiles en el periodo de transición’ (Mercantile Categories in the Period of Transition); 20,000 copies were published in periodicals of the ministries of industry and of finance.39 It included a flattering biography of the author.40 Mandel wondered if this was ‘to neutralize in advance certain ill-intentioned criticisms of my spiritual family [the Fourth Intemational]?’41 He treasured in his wallet a banknote personally signed by Che: more than a currency note, it was a proof of trust. Mandel admired Che’s courage in inviting him to Cuba for a debate that the Soviets and orthodox Communists had to accept, however grudgingly. He praised Che as a theoretician, a leader in the tradition of Marx, Lenin and Trotsky.42

Looking back in 1977, Mandel considered Cuba’s open debate on the economy ‘the big turning point’ in the Cuban revolution.43 Behind that debate had raged another, not held in public. This debate concerned the revolution’s sociopolitical orientation, the role of the workers and the issue of power. That is, along with the question of the law of value came the issue of how much freedom the proletariat would have to make its own decisions. As Mandel saw it, though Che triumphed in the public debate, he was defeated in the hidden one. Guaranteeing freedom was a political problem: it required the creation of workers’ councils and popular assemblies. Such organs were never developed.

When Che left Cuba in 1965, he was the most popular leader on the island. If the voice of the people had been heard, Che would have won the political as well as the economic round. But, as Mandel said, ‘Che did not want to appeal to the people. He did not want to split the party openly. This is why he left after his defeat.44 In his 1964 correspondence Mandel had acknowledged that he did not dare put some of his impressions on paper.45 Did he already suspect that the debate would have a tragic outcome?

On Mandel’s departure Luis Alvarez Rom assured him that he was always welcome; a request would be sufficient to assure an invitation.46 There was a rumour that within a few months Castro would officially invite him `so I can deal a bit with his affairs’.47 He returned to Brussels in a hopeful mood:

The influence of the Stalinist ‘sectarians’ (that’s what they’re called there) continues to decline . .. Slowly a new vanguard is forming, one that is close to our ideas . . . The revolution is still bursting with life, and on that basis democracy [can] bloom.48

He had also been assured that ‘the group around Che was noticeably stronger’ and that ‘workers’ assemblies would soon be started’.49 Was this the beginning-of workers’ self-management, however modest? The promise did not amount to much, but Mandel dosed his eyes to its limits. He reacted negatively to Nelson Zayas’s advice to pressure Che and to convince him that he’ll lose the battle if it’s only fought in the government and bureaucratic arena’.50 The people’s support for the government must not be underestimated.51 The die was not yet cast: ‘Nothing was definitely decided yet in the economic discussion.’52 Mandel did not want to hamper Che and Fidel in their conflicts with the pro-Soviet currents. This would not have been appreciated, either, by the swelling multitude of radical youth in France and elsewhere for whom Che was nearing the status of hero. Mandel’s reaction disappointed Zayas and hastened his decision to turn his back on Cuba and complete his study of French in Paris. He asked Mandel to use his influence with Che to secure the necessary exit visa.53

Mandel’s thoughts about Cuba changed only slowly. The Latin American revolution came to a halt: Salvador Allende lost the Chilean election in September 1964, there were military coups in Brazil and Bolivia, and leftist guerrillas in Peru and Venezuela were defeated. Cuba paid for these failures with its growing dependence on the Soviet Union. This was an arid climate in which social democracy could not thrive. As Mandel frankly admitted to ex-Trotskyist Jesus Vazquez Mendez,

I subscribe to your opinion that participation by the people is essential … . I had heard that management of the enterprise would come into the hands of the trade unions after their leadership was replaced; but the latest news is that nothing has happened. I’m sorry about it, and like you I’m afraid that if things are left to take their course, the result will be an economic impasse. Maybe I’ll go to Cuba again in l965 and can give the debate new impetus.54

But he didn’t visit in 1965, and he never saw Che again, not even when Che was in Algiers to address an Afro-Asian conference at the end of a trip through Africa in February that year. Never before had Che come out so strongly against the Soviet Union. He declared that ‘the socialist countries are, in a way, accomplices of imperialist exploitation’. Before all else oppressed peoples had to be helped with weapons. ‘without any charge at all, and in quantities determined by the need’.55 Che’s words took root in the fertile soil of Latin American campuses and the radical milieu in Paris, where his speech was duplicated and distributed,56 and the Union of Communist Students (UEC) invited Che to Paris for a debate on Stalinism.57 The initiative came from the EUC left wing, in which Mandel’s fellow-thinkers played a prominent role. Six months earlier they had been received by a deputy minister of industry, a dose colleague of Che’s.58 One of the group’s spokespeople, twenty-seven-year-old Janette Pienkny (Janette Habel after 1966) traveled regularly between Paris and Havana. She contacted the Cuban ambassador, who relayed the invitation to Che by phone. Meanwhile Mandel was attempting to get a visa for Algeria. After Che’s speech, Mandel had phoned him his congratulations. Che had immediately agreed to a meeting but it had to he the following day, a Monday, because he was about to leave.59 But that Sunday Mandel sought vainly to make contact – at home and at the embassy- with the ambassador and the consul. Without a visa, ‘they wouldn’t have even let me telephone from the airport . . . I finally decided, heartbroken, to miss the meeting that had meant so much to me.’60

The debate in Paris never took place. The Communists Party put a stop to it.61 Che was now viewed as a heretic, not only in Moscow but also within the Communist parties. Algiers was his last public appearance. He went to the Congo and Bolivia to help break the isolation of their revolutions, a solidarity that he summed up in his testamentary message with the call -Make two, three, many Vietnams!’62 That slogan became the catchphrase for the generation of ’68.

The Death of Che Guevara

Though a trip to Cuba had proved impossible in 1965-6, Mandel’s thinking about the Latin American revolution continued to develop. He praised the young philosopher Régis Debray, a student of Althusser’s. In a January 1965 essay in Les Temps Modernes Debray had characterized Castroism as the Latin American version of Leninism. Mandel described it as “an excellent piece’, though he dismissed out of hand Debray’s idea about spontaneous party formation.102 Mandel expressed himself more cautiously About Cuba’s relationship with Moscow: ‘politically they continue to have their own line. . . What is bad, however, is that [Castro] made a series of moves to satisfy the Russians (like his attacks against the Chinese and against the “counter-revolutionary trotskyists”).’103 Ac the final sitting of the Tricontinental Conference in Havana’s Chaplin Theatre, Castro had spoken of ‘the stupidities, the discredit, and the repugnant thing which Trotskyism today is in the field of politics’.104

Mandel thought that must be a genuflection towards Moscow, .camouflage for the call to armed struggle that Moscow might interpret as a concession to Trotskyism. In it confidential meeting with Victor Rico Galan. Castro’s representative in Mexico, Mandel later learned that Castro regretted his statement. Galan had pointed out to Castro that the attack ou Trotskyism was unfounded. Admitting his mistake, Castro had asked Galan to give him `A month or two to make public corrections of this at the proper time’.105 At the end of May Mandel unexpectedly got an invitation to visit Havana. The Cuban ambassador spoke of a personal invitation from Castro and promised a meeting with President Osvaldo Dorticós.106

In June 1967 Ernest aud Gisela arrived at the former Havana Hilton, re‑christened the Free Havana but with its former splendor carefully preserved. At the hotel’s bar, replacing the Americans of earlier times, were Russians and few East German technicians. Politics was never far away, even at the hairdresser’s, as Gisela discovered: ‘The girl sitting beside me was reading Lenin, and on the other side a woman was reading Mills’s The Marxists.’107

A beautiful English-speaking guide took care of all the formalities, including credit cards and a shabby Cadillac with chauffeur. Gisela immediately fell in love with the impoverished country. She sent Meschkat enthusiastic reports about their wanderings and the encounters in tobacco and sugar factories, on plantations and in prisons and schools. ‘Everything is exquisite and for us so encouraging and hopeful.108

Their programme was overloaded. Ernest often returned only at l:00 or 2:00 in the morning from a debate or lecture at the university or a party school. The atmosphere was frank and candid. as were the meetings with the host of Latin Americans attending the first conference of the Organization in Solidarity with Latin America (OLAS), held in Havana at the beginning of August.109 Ernest and Gisela were furious when the Czechoslovakian paper Rudé Právo published three pages slandering Che on the day that Soviet premier Kosygin arrived. Gisela wrote, ‘You should just hear how they talk about the Russians in all circles here, from the highest to the lowest, I’ve never heard such talk, from socialists yet.’110 Typically, Castro charged the Venezuelan Communists with falling the guerrilla movement.111 Though Cuba was dependent on the Russians, Castro continued to provoke them.112