United States:

Polarization and a repressive environment

By Fernando M. García Bielsa

December 23rd, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

The latest incidents of police brutality and racist killings in many U.S. cities are not a recent phenomenon. They are long-standing events, stemming from the days of slavery and, as now, developing alongside the violence of paramilitary and white supremacist groups.

The warlike projection of the country and its having reached the point of being permanently involved in a series of wars in various confines, has permeated the psyche of thousands of people and is reflected in a growing militarization at the domestic level. In addition to police brutality, it is clearly expressed in the proliferation of violent groups, as well as in government agencies such as the prison system, the militarization of the border with Mexico, and violence against immigrants.

In addition to the violent and racist tradition with which the U.S. nation was formed and the impact of imperial militarism, there are also the social fractures, polarization, and growing inequalities that this society has shown in recent decades. There are tens and tens of millions of people inserted in a vicious circle of residential segregation in unsafe neighborhoods lacking basic services.

Let’s look at some background

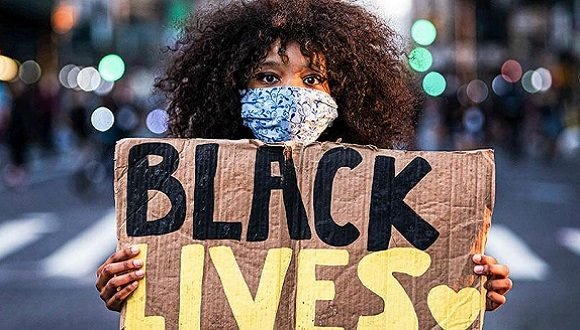

Protests in New York against racism. Photo: The New York Times/Archive

The question of race and racism against Blacks has been a major factor in shaping American culture and policy from colonial times and the formation of the republic to the present. Much of national politics revolves around them. The historical and current location of African Americans is – in many ways – central to the country’s problems.

In turn, Black political movements and activism have historically been at the forefront of struggles for progressive change in the United States, a vast and diverse country where class and other movements have been co-opted or fragmented. This is influenced by historical reasons, immense institutional obstacles, as well as the dimensions of the country, the tensions arising from the multi-ethnic character of its population, and the growing weakness of the labor movement.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, so-called “communities of color” began to understand that society, as it existed, would never address their needs as they were perceived and felt. It was in this period that exploring their cultural heritage and building their own institutions became their greatest strength. The Black Power slogan had electrified Black communities across the country.

A dramatic transformation in the self-image of Black people began, in the context of one of the most effective social movements to date in the country, of racial pride, collective consciousness and community solidarity, with enormous repercussions in society as a whole.

After the impact of the great struggles and mobilizations of the Black civil rights movement, it became evident to sectors of power that the strength of such movements was being enhanced given the serious social problems in those communities. For this reason, since the 1960s, a whole series of government programs and assistance projects for the “development” of marginal areas and Black communities had been spreading.

Among the results of these programs was the strengthening of reformist groups and economic interests, as well as contributing in the long term to the formation of a whole layer of African American and Latino professionals and politicians with possibilities of access, public presence, and supposed representation of the interests of so-called ethnic minorities.

The Black bourgeoisie, including that which developed during the Obama administration, has continued to make false promises of inclusion. Except in the recent context in reaction to the wave of killings and police violence, organized political activism by African Americans has reached this stage after a long period of ebb.

Black groups have remained atomized, uncoordinated, focused on immediate economic and social concerns, and their energies have become diffuse, marked by the needs and life emergencies of their social bases, internal divisions, and the social polarization in their communities. External manipulations of all kinds do the rest.

The appearance of greater political influence by the Black population given the access of a few of their own to positions of some visibility has been misleading. Despite some advances in participation and representation, Blacks continue to fare worse than whites in having their political preferences and interests legislated.

The increase in class diversity that has taken place within these ‘communities’ and the nefarious role played by the Democratic Party in presenting itself as a champion of the underprivileged when in fact it is subject to the interests of the country’s financial elite, were felt.

A polarized and contentious society

Black Lives Matter mural on a street in Washington Photo: CNN.

The United States shows a growing number of very deep social divisions. Racism and the dangerous ideology of white supremacy is a serious obstacle to social cohesion, and is sometimes conducive to and at the root of serious outbreaks of violence. Demographic trends, some warn, suggest that the nation will not be sustainable in the long term unless marked inequalities between populations of diverse ethnic backgrounds are corrected.

Analyst Tim Wise said (on the Truthout website, March 2, 2012) that, in 25 or 30 years when non-whites will be half the population and the majority in several states, it will not be sustainable for the country to maintain that population as it is now. Blacks today are three times more likely to be in poverty than whites, twice as likely to be unemployed, with several times less assets and with an income less than the other half of the citizenry, and with nine years less life expectancy.

Behind that reality, repressive conceptions prevail. These are not only fed by overflowing militaristic mentalities or fears of ungovernability, but they are backed up by calculations of profit generation. These are derived from the so-called wars on drugs, mass incarceration in private prisons, outsourcing to private “security” agencies, and institutionalized repression against immigrants and marginalized populations.

The focus of repressive state activity is directed against Black groups and progressive organizations, which has led to the violation of civil liberties, the criminalization of social movements, increased surveillance and infiltration of Black, Latino and poor Muslim institutions and communities, including the deployment of undercover police, informants and intimidation in homes and public spaces.

–

A woman protests in New York against the ban on Muslims in Trump. Photo: Stephanie Keith/ AFP.

Muslim communities in the country face an environment of growing intolerance and hostility since the September 11, 2001 attacks. State and local police forces gather information and spy on law-abiding Muslim citizens. They become targets of violence as an extension of racism and xenophobia to our day, virtually demanding submission and near abandonment of their cultural and identity expressions.

So far, anger and despair have replaced the organizational strength and momentum of the civil rights era.

Trapped in almost immovable racist structures

A woman affected by the tear gas launch during a protest in Boston in June. Within six nights, the agitation spread to every major city in the country and became a general protest against systemic racism in the United States. Photo: Brian Snyder/Reuters.

U.S. society is deeply fractured politically and across class, regional, economic, ethnic, religious, and cultural interests. Racial issues intersect with class differences and class oppression, and are often instrumentalized for political purposes. Levels of violence resurface; disparities are enormous. There are pockets of the population where people live in constant paranoia.

Even after the great rebellions against racism and the successes of the civil rights movement in the middle of the last century, including the partial dismantling of many of the legal structures that supported segregation, racial inequality remains a palpable fact. The racial chasm is widening and has not been altered by changes in government.

Racial prejudice in the United States has a strong negative impact on the lives of African Americans. It expresses itself in forms of discrimination in all areas and conditions of existence: segments of the population caught in a vicious circle of residential segregation, inferior opportunities for education or health services, marginality, increasing rates of incarceration, and discrimination in employment. Black workers receive 22% less than white workers in their wages, with the same levels of education and experience. The average income of African American households is just over half that of white households.

In most cities and urban areas of the country there are separate areas where the Black population resides,. This reflect the historical racial segregation that shaped the country and the policies created in the past to keep Black people out of certain neighborhoods. Many of these slums have high levels of poverty and face an intense and unwanted police presence.

In such an atmosphere and because of such deep-rooted prejudices, any activity, no matter how innocent, in which a Black man is involved generates suspicion, alarm and often danger to his life. Consider also that the rate of Black citizens in prison is five times that of white citizens. Despite being only 13% of the population they constitute 40% of all incarcerated men.

Highly peaceful neighborhoods coexist with others where violent death ravages the usually poor. Entire communities of Black, Latino, Muslim or Asian populations feel their communities are under increasing police occupation.

U.S. society has not been able to address the root causes of the outrage and anger that consume millions and are behind the recent powerful demonstrations against repression and racism. Neither politicians nor public institutions have established effective government programs to mitigate at least these gross inequalities, ultimately produced by the prevailing capitalist system.

On the other hand, what that society has done quite effectively is to divide and co-opt many of the struggles and organizing efforts that were going on in those communities.

The re-emergence of a “new Jim Crow,” that is, of a climate of brutal segregation, based on the mass imprisonment and repeated police killings of unarmed Black men, shows that the old systems of repressive control have increased in the present, always maintaining the dividing line of skin color.

In contrast, white hate groups, nationalists and racists, as well as their armed paramilitary branches, proliferate and carry out violent actions, often being overlooked or even in collusion with authorities in certain regions. Many of President Trump’s words and actions have seemed to encourage such groups.

All of this demagogic rhetoric, which has a fascist slant and is a mirror of the country’s war policies, encourages desperate sectors to organize themselves into militias to wage crusades of various kinds. It is a propitious environment when more than 300 million firearms, many of them of high caliber, are in the hands of the population, when a part of the hundreds of thousands of war veterans live with their frustrations, resentments and traumas of their war experiences.

In this context, hundreds and hundreds of right-wing armed militias throughout the country are operating, whose ideology and motivations are a combination of paranoia, fear and aggressive claims of their rights to carry firearms, receptiveness to elaborate conspiracy theories and extreme anti-government anger. Many claim that the country’s government has been subverted by conspirators and has become illegitimate, and therefore see themselves as patriotic by organizing themselves paramilitarily, confronting the authorities, and fomenting racial warfare.

An increasingly complex urban [and national] future

Stop killing us. Photo: Raul Roa/Daily Pilot

Many authorities, in conjunction with the media, continued to criminalize protests and progressive groups, going so far as to characterize minor actions as violent crimes and even “terrorism.

Raising alleged “security” interests, the so-called program to Counteract Violent Extremism (CVE) was begun under the Obama administration (2009-2017), that openly resembles the repression against radical groups and the COINTELPRO program of the 1960s and 1970s, and that was added to the actions deployed after the passage of the Patriot Act in October 2001 and other actions.

On the basis of sections of that law, federal agencies are able to make more and more inroads into areas of civil and personal life. The FBI, for example, can demand information such as telephone and computer records, credit and banking history, etc., without requiring court approval and without being subject to controls on the use that the feds make of such personal information.

Abuses and violations of the law often occur. Such is the case when attention is drawn to controversial sections of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978, which allow for the conduct of mass spying on Americans communicating abroad. Recently the National Security Agency (NSA) has admitted to improperly collecting several hundred million phone calls from U.S. citizens.

According to William I. Robinson, a specialist on these issues, in his January 2018 article Global Police State, as war and state repression are privatized, the interests of a wide range of capitalist groups converge around a political, social, and ideological climate conducive to the generation and maintenance of social conflict.

For some time there have been signs that the government was anticipating the possible occurrence of serious civil problems and disturbances.

A video entitled “The Urban Future and its Emerging Complexity,” created by the U.S. Army to be used in the training of special forces, is revealing of the mentality and attitude in state entities regarding citizenship and the so-called “problems” that the government must be prepared to face through the use of martial law.

Already in 2008, a report from the Army Defense College stated that in the face of the possibility of a wave of widespread civilian violence within the country, the military establishment planned to “redirect its priorities under conditions of exemption to defend domestic order and the security of the people.

In its 44 pages, the report warned of the potential causes of such problems, which could include terrorist attacks, unanticipated economic collapse, loss of legal and political order, intentional domestic insurgency, health emergencies, and others. It also mentioned the possibility of a situation of widespread public outcry that would trigger dangerous situations and that would require additional powers to restore order.

In recent years, the U.S. state has radically expanded its punitive and surveillance capabilities. To limit protests, control dissent and popular opposition, as part of the well-known actions of the FBI and local police forces in previous decades, the system used administrative and legislative methods, espionage and covert infiltration, discrediting actions, massive “preventive” arrests, police attacks even against authorized peaceful protests, and so on.

The FBI’s budget for funding undercover agents, much of it within progressive organizations, rose from $1 million in 1977 to several tens of millions today.

People march with signs, protesting police violence and racial equality in Washington, USA, on September 5, 2020. Photo: Leah Millis / Reuters

See also:

In the United States, Black deaths are not a flaw in the system. They are the system.

You must be logged in to post a comment.