Granma 299

Cyber-business media against Cuba

Media dependent on cyber-business against Cuba

They are classified as independent or alternative. But it is enough to go after the route of money that encourages and articulates them to know on whom they depend and to which editorial line they respond…

Author: Walkiria Juanes Sánchez | walkiriajuanessanchez@gmail.com

December 28, 2020 20:12:52

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Photo: Granma

A media network is trying to legitimize the US hegemonic vision of democracy and freedom in Cuba. With their annexationist strategy, they constantly intoxicate the social networks with distorted information about almost everything that happens on the island.

They call themselves “independent or alternative”, but it is curious that all those who run CiberCuba, ADN Cuba, Cubanos por el Mundo, Cubita Now, Cubanet, Periodismo de Barrio, El Toque, El Estornudo and YucaByte, among others, live abroad, mostly in the United States, and their communication strategies are the formula for the political design that prevails in that country.

Maykel González, from the subversive site Tremenda Nota, publicly stated that, during his stay in the U.S., specifically in the state of Ohio, he attended an academic program with professors from the University.

“There was a contact with officials in charge of attending the press at the State Department, I had a private appointment with State official Priscila Hernandez,” Gonzalez said.

The June 2004 report of the Commission for Assistance to a Free Cuba records the main subversive lines against the Greater Antilles, including the promotion of press projects. Since then, all the administrations after President George W. Bush adjusted their media design to each context.

The State Department, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) of that nation, finance this media machinery that has benefited from the more than $500 million that the White House has allocated in the last 20 years for subversion in Cuba.

In order to receive the funding expeditiously, several of these counterrevolutionary digital publications have been registered in other countries as non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Such is the case of the sites El Toque, through the collective Más, based in Poland, and El Estornudo, created in Cuba, and later legalized in Mexico as an NGO.

Carlos Manuel Álvarez, director of El Estornudo, arrived in Cuba on November 24 to join the San Isidro media show.

Abraham Jiménez Enoa, who was a participant in that same website, expressed that he does not know how much the total financing of the “media” is, because everything is done from the outside. “The collaborators that make the magazine charge for work, with a fixed salary of 400 CUC. Until I left, El Estornudo was financed by the NED and Open Society,” said Jiménez Enoa.

These so-called alternative and independent media disqualify themselves when it is revealed where their livelihood comes from, even though sometimes they try to divert attention from the origin of the money.

The researcher of the Center for Hemispheric and U.S. Studies, Yazmín Vázquez Ortiz, explained that financing, training and technical assistance are pillars, from which the conditions that exist in the societies that can be the object of intervention are taken advantage of, to promote resistance movements that can foster the change that the U.S. wants.

Those who lead and collaborate in these spaces do so through organizations based in U.S., European or Latin American territory.

The deputy director of this same Center, Olga Rosa González Martín, pointed out that since they operate as a private organization, they receive private funds, which can come from any individual, from any corporation at the international level, making it more difficult to link an entity with a specific government, and with its foreign policy objectives in a given country.

The Institute of Peace and War Journalism, Factual, Distintas Latitudes, Swedish Human Rights Foundation, Editorial Hipermedia, Diario de Cuba, Cubanet, Sergio Arboleda University, and many others, function as contractors for these mercenary press projects.

José Jasán, from the subversive site El Toque, stated that “the most acceptable thing for ‘the company’ is that by going to train a group of Cubans, it gives them the opportunity to pay them directly.

Elaine Díaz Rodríguez, from Periodismo de Barrio, said that they went to international cooperation. “At first, it was financed with the savings I was able to take to Cuba from the Lima Scholarship, and later we were able to carry out a pilot project with the Swedish Foundation for Human Rights. We achieved an alliance with the Norwegian Embassy, through which we are here,” she said.

In this design, the Cuban-American Aimel Ríos Wong stands out from NED. As Head of the Cuba Program, he distributes the funds approved to dismantle ideological and cultural paradigms from outside and inside the Island.

Maykel González, from the subversive site Tremenda Nota, commented that Ríos Wong called him, went out to “take a walk in Washington”, and recognized him as someone who has made himself present, who has been in constant dialogue with the actors, both from journalism and from civil society.

“We are working with about $7,000 for a quarter, from which we do the planning of the work, and it is allocated by all the fees we have to pay,” said Maykel Gonzalez.

As a strategy, they select their future leaders, train them, reward them, finance them, stimulate them, make them visible, bring them together, empower them, guide them, and give them spaces and stands.

“What they say is: no, but nobody tells me what I have to write, nobody tells me what the editorial line of my page is or of the articles I write. They don’t have to tell you, you already have that line assumed, you get funding, because you already said those things, and you know that if you don’t say them and don’t follow that anti-government line you’re not going to receive the funding,” noted Javier Gómez Sánchez, a specialist in audiovisual media.

As the computerization of the country has advanced, said Gómez Sánchez, people have been having greater access to the Internet, and this war has been increasing and organizing, because their possibility of reaching certain sectors of the population with this type of media manipulation has increased.

Dr. Ernesto Estévez, member of the Cuban Academy of Sciences, reminded that this phenomenon is something that has been working for many years, with the aim of reversing the Cuban Revolution, of making a capitalist restoration.

Public sources of the US government itself show the increase of these funds during the last years, just when the Cuban State is advancing in the transformations of the new economic and social model.

This is confirmed by a call from the US Department of State’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor to fund proposals related to civil and political rights in Cuba, amidst the provocations put forth in recent days.

Together with the imposition of restrictive economic measures and the complex epidemiological scenario of COVID-19, the enemy media lined up to discredit the Cuban government’s management and delegitimize the social system.

“It has to do with the fabrication of opinion matrixes, which have two essential characteristics: first, they are created to manage the discontents that exist, related to certain issues, and to direct them against the government, socialism, and the political system; and second, to try to promote in Cuba a liberal thought, based on liberalism, which is the ideology of capitalism,” exposed the psychologist Karima Oliva Bello.

In the communicational framework, there are the so-called influencers with hypercritical tendencies, created to generate empathy and ideological tendencies in thousands of followers, through social networks.

The enemy press projects, in this scenario, are identified as instruments of the US Government in its unconventional war strategy against Cuba.

Whoever consumes the news published by the subversive media could come to believe that Cuba is a country that is collapsing. However, this is a nation that is living a different reality.

No impunity for price-gouging in Cienfuegos

There will be no impunity for the abusive prices and speculators that affect the people

Structures dedicated to the confrontation of price violations in the province of Cienfuegos perfect control mechanisms

Author: Julio Martínez Molina | internet@granma.cu

December 26, 2020 00:12:04

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

n Cienfuegos, inspections were more rigorous and more demanding in response to price violations committed by cartwrights, illegal drivers and self-employed workers who sell products that are not part of their activity. Photo: PERLAVISION

Cienfuegos: A sort of battle is being fought in Cienfuegos, day by day, against those who try to thrive on their fellow men and, by the way, affect the purposes of the Ordering Task.

Since October, a progressive upward trend in prices began to be verified in the province, especially in the sector of self-employment in the sale of food products, textiles and hardware. Also in the services provided in hairdressing salons, barber shops, manicures, cafeterias and …

From the very beginning of the phenomenon, the Provincial Confrontation Group began to counteract it, but it became more acute, and today the authorities of the territory themselves recognize what this implies.

Fara Iglesias González, an official of the provincial government and coordinator of the Confrontation Group at that level, explained to Granma that the control was systematized to prevent impunity. However, in spite of the high number of fines applied (more than 3,000 only since 15 November) and the certain contention derived from this action, illegalities continue to appear”.

The official emphasized that the rigour and “the demand in the inspections will be raised in the face of price violations committed by cart drivers, illegal drivers and self-employed workers who sell products that are not part of their activity.

He highlighted the integration into the work of various regulatory authorities. “We can say with complete certainty that where we detect this indiscipline, illegality or violation, we order that it be sold at the price set by the new resolutions,” he said.

“We also maintain a synergy with the information provided by the Price Observatory group.

On the basis of the complaint, they faced criminal acts associated with the illegal sale of cement, as well as those who offered the onion “leg” at 250 pesos, when the established tax is 40 pesos. In the same period, there were 23 seizures, and the State Traffic Unit withdrew a considerable number of licenses from coachmen.

According to the first secretary of the Party in Cienfuegos, Felix Duartes Ortega, “responsibility is vital in a matter of maximum importance that is not at all alien to the Party’s militancy”.

He considered that aside from the actions carried out in recent months and the intensity charged by these in recent days, in the confrontation with the rise in prices in certain activities, “we recognize that we have not yet been able to stop the phenomenon.

Duartes Ortega pointed out that, only in the last week more than 600 fines were applied in the province. He added that in the last 15 days, some 20 licenses were withdrawn from wheelbarrows, eight urban and suburban agricultural points were closed and three private cafeterias were closed.

But in his opinion, this is not enough. The struggle must be redoubled and the population informed of how much is being done.

In the opinion of the governor of Cienfuegos, Alexander Corona Quintero, “the Administration Councils must have the sufficient capacity to analyze the prices and to top them, for which it is necessary to analyze each case, product by product. To form a price, it is necessary to create a cost sheet. No one can invent or raise prices unjustifiably, here abusive prices against the population will not be allowed”.

Corona Quintero meant the articulation, from the province, of work groups that are visiting each place, as is done in the municipalities with their systems of confrontation, and their respective structures, because impunity will never reign. We are in that battle and we will win it, he remarked.

ALSO VIOLATED IN THE STATE SECTOR

The battle also involves the state sector. A recent control operation led by the Provincial Confrontation Group warned of numerous irregularities in the state agricultural market located on Calzada de Dolores, in Cienfuegos.

José Luis Calzadilla Olivera, a government official, detailed that products for sale were identified without being in the affidavit, large price alterations and weighing violations. For example,” he said, “we weighed the banana and people were not charged the actual weight, so they were being cheated.

“In addition, we were concerned that these serious violations were occurring in the absence of the administration. Those in charge of the warehouse were not fulfilling their responsibilities. They had 15 boxes of tomatoes in storage, and only one of the stalls offered the product. There was something there, we could not get to the end, but we managed to get the tomato out for commercialization at the established rate,” he added.

Other incidents were reported by representatives of the Integral Direction of Supervision in the territory. Martha Lendestoy Moreno, inspector, detailed that, “within the market, specifically in the points of sale of the credit and service cooperatives Mal Tiempo and Agustin Cabrera, the information boards did not publish the prices and, the consumers referred that they had bought the pound of tomato at 10.00 cup, when the current amount approved by the Governor is 5.00 cup. This determined the application of the corresponding decrees, and the duplication of the amount of the fines for several infractions”.

Cuba Energy Beats US Blackout Attempts

Cuba’s energy beats back the blackout that

the White House is trying to impose on us

The US government’s economic, commercial and financial blockade against Cuba has caused losses of about US $5.57 billion, and in all areas of the country’s productive and social life, this scandalous figure translates into concrete damage where the energy sector is not exempt

Author: Gladys Leidys Ramos López | internet@granma.cu@granma.cu

December 25, 2020 00:12:36

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Another activity bicaused by the inhumane blockade is electricity. Photo: Julio Martínez Molina

From April last year until March 2020, the economic, commercial and financial blockade by the US government against Cuba has caused losses of around $5.57 billion dollars, which represents an increase of more than a billion dollars over the previous period.

In all areas of the country’s productive and social life, this scandalous figure translates into concrete damage. This is what happens with the energy sector, since of the total hostile actions recorded during that stage, 24 have an impact on this sector, including those related to the arrival of oil in Cuba.

Raúl Pérez de Prado, General Director of Cuba Petroleum (Cupet), has explained that, in this respect, the group had direct damages of more than $52 million. He detailed the harassment suffered by suppliers by customs authorities from different countries, which audit them in search of violations with respect to the provisions of that genocidal and extraterritorial policy, He pointed out that the reduction of operations of shipping companies and airlines with Cuba has increased the cost of freight and has made it difficult to send goods to our borders.

Another activity biased by the inhumane blockade is electricity. Ramón Miguel Pedrera Valdés, general director of this area in the Ministry of Energy and Mines (MINEM), clarified that in the last year the negative consequences for the Electric Company has been some $31 million, reflected mostly in the company Energoimport.

“The damages to foreign investment projects dedicated to renewable energy sources are an example of the extraterritoriality of the blockade. Due to the entry into force of Title III of the Helms-Burton Act, the investor even requests the successive tract of land where the wind farms will be built, for example, to ensure that, before 1959, the area was not owned by the United States,” he esplained.

Mining is one of the activities that has suffered in these years due to the illegality of the blockade. Juan Ruiz Quintana, general director of this area in MINEM, listed among the effects the payment of higher export and import insurance premiums and high transportation costs, as well as the cost of banking operations. He gave as an example that the damages of the Cubaníquel company amount to USD $156,105,700.00 while the Geominsal group suffered losses of more than $6,684,898.00

However, concluded Ruiz Quintana, the productions of the sector in this 2020 are over 90%, and in 2021 the premise is to “reinvent ourselves once again and respond with effective solutions, as until now, without giving up”.

Providence is on his side

Providence is on his side

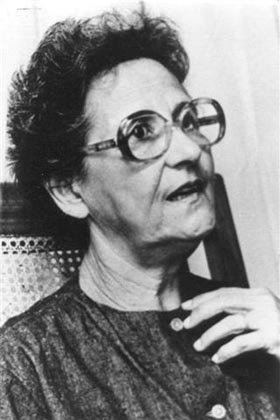

Leopoldina Grau Alsina (Pola) received the mission from the CIA to assassinate the Commander in Chief in the 1960s

By LUIS BÁEZ

August 13, 2007

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Considered one of the main agents of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in Cuba, Leopoldina Grau Alsina (Pola), was the person who received the death capsules to assassinate Fidel Castro in the 1960s.

LEOPOLDINA GRAU ALSINA.

Arrested in June 1965, she was sentenced by the courts to 30 years in prison.

In the interrogations she revealed how close they had been to carrying out the assassination of the maximum Cuban leader during a visit that he made to the cafeteria of the Habana Libre Hotel, a fact unknown until that moment by the leadership of the Revolution.

In 1978, in the course of the revolutionary government’s dialogue with the Cuban community abroad, she was released. She served 14 years in prison.

Pola, 63, granted me this interview before traveling to the United States. In it, she narrates not only the famous plan of the capsules to assassinate the Commander in Chief, but other aspects of her activity such as the campaign for the Parental Power. A woman of high stature and aristocratic appearance, she unfolded with ease and responded extensively during the course of the conversation, which was recorded with her authorization.

Why did you conspire against the Revolution?

I was anti-Batista. I worked with Carlos Prío. I also worked with Raúl Rodríguez Santos. That led to my having to go into exile in the United States in 1958. When I arrived in Miami I went to live in the house of José Braulio Alemán (Neneíto).

When Fulgencio Batista escaped, I was ready to return to Cuba, but Prío asked me to stay because a coup was being prepared for January 4. With that objective in mind, Tony Varona was already in Havana and Aureliano Sánchez Arango was traveling in a boat to the island with weapons. But Castro beat us to it.

My daughter was studying. I waited for her to finish the course before returning to Cuba.

When did she return?

At the end of May. The news that arrived in Miami stated that the Revolution was red. What I was able to verify upon my return.

I have never been a communist. I was always against the communists. I never sympathized with the communists. I found out that they had taken away my friends’ property, my family’s property. That made me feel bad. I got into a rush, a delusion to overthrow the government. My son had to take me to a psychiatrist.

He found me delirious with guilt. He cured me, but I made him counter-revolutionary and he ended up leaving for the United States.

Already a master of my way of being and thinking, I wanted to find someone with whom to start working against the situation, since I could not do anything on my own. I contacted the person who represented Tony Varona in Cuba, since he had returned to Miami. I’m talking about the second semester of 1960.

Who was that person?

Albertico Cruz, an old friend from Machado’s time, a real front-runner who was acting as the Rescue Coordinator.

I also made contact with former Colonel Manuel Alvarez Margolles, who was the military head of that organization, and we started working together.

What influence did Margolles have on you?

A lot. I was extraordinarily subdued by his way of being. Honestly, anything he told me to do, I would have done.

Were you given any responsibility?

I was appointed as the female coordinator, with Albertina O’Farrill as the person responsible for the asylum.

At that time Tony Varona asked me to send a trusted person to Miami.

Who was chosen?

Rodolfo León Curbelo.

What year was that?

February 1961. Two months before the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Did you know about the invasion?

Leon Curbelo already had instructions about it.

Who informed him?

Tony Varona. He was a member of the Democratic Revolutionary Council. He sent me a letter giving me instructions. The failure of the invasion came and I had to take Mario del Cañal and others into custody.

In which embassy did you isolate them?

In the Venezuelan Embassy.

Did you promote the campaign for the Parental Power?

I spread the rumor that the communist government would put into effect on January 1, 1962 a law whereby all children between the ages of three and ten would be placed in Children’s Circles and would only be allowed to see their parents twice a month.

Those over ten years of age would be transferred to other circles in the provinces and no minor would be allowed to leave Cuba without special permission.

According to this law, the State would be the absolute owner of the children and the parents would lose their rights over the children and many would be sent to Russia. We came to write and print a false law of the revolutionary government in this sense.

Why did you do this?

As a way to destabilize the government and for the people to begin to lose faith in the Revolution.

Quite a cynical attitude.

We were at war with the government. In war everything is allowed.

Who were your collaborators?

My brother Mongo, some sectors of the church and various friends.

Who was involved in sending the children to Miami?

My brother Mongo and I.

What name did you give to that operation?

Pedro Pan (Peter Pan). A fairy tale in which Pedro Pan took the children on a flight to achieve a better way of life.

When did the operation begin?

In the first months of 1961. My brother Mongo received a letter from the Catholic Welfare Bureau in Miami in which they proposed a plan to get children out of Cuba by providing passports and special visa waivers, taking them on commercial airplanes to the United States.

Who supported her?

Beatriz (Betty) Pérez López, Hilda Feo, Alicia Thomas, Marie Boisssevant, wife of the Dutch ambassador; Father Raúl Martínez, parish priest of Santa María del Rosario Church; Wanda Foschini, assistant to the Italian ambassador; the German ambassador, Karl Von Spretti. In the airlines we had Ulises de la Vega from KLM and Julio Bravo from the Pan American. The person in charge of stamping the false visas in the passports was Borico Padilla. The most important of all the collaborators was Penny Powers.

Who was Penny?

A British intelligence agent who served as our liaison with the British Embassy. Through her we sent and received communications with Monsignor Walsh through the diplomatic bag of the British. It had the code name “Kilito”.

What was the mechanism like?

In order to leave Cuba, children needed passports with valid visas or special visas. Since there were no diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba, it was practically impossible to obtain visas.

The State Department contacted my brother Mongo and told him that they had appointed Irish Catholic priest Bryan O. Walsh, director of the Catholic Diocese of Miami, as the coordinator of the program in the United States and he was authorized to sign the visa waivers.

How did the visas enter Cuba?

Through diplomatic contacts.

How did they know their numbers?

We received all the passport and visa numbers from the United States by radio. We would tune the radio on the modulated frequency and listen to a coded song.

What song?

If they played Granada, it meant that there was no message, but if we listened to Jascha Heifetz’s violin solo, it meant that a voice was coming up counting from one to ten, then it gave a long series of number combinations that we decoded the same Mongo as I did from a secret book containing the keys. Ivan Ledo, a person we trusted, sometimes intervened in this operation.

With the visas in his possession, what did they do?

Once we received them, we attached them to the passport. This work was done between noon and three o’clock in the afternoon on the porch of the residence of my uncle -Ramón Grau San Martín- on Fifth Avenue and 14th Street, in Miramar.

Through individuals we trusted, we sent the passports to another person in the distribution chain who in turn passed them on to another intermediary. There were five or six steps for distributing the passports. You could only meet one person at each level.

Did the Americans have any records?

When people arrived in Miami they would ask, “did they charge you or didn’t they? If they said that the visa had cost them some money, they would inform us. We confirmed. The person who had applied for the visa the most would never have the problem solved again. We would close the doors on them.

What other contact did you have in the United States?

For the mail, it was Margarita de la Riva, on Calatrava Street and Coral Gables, a suburb of Miami.

Did they receive financial assistance?

Father Walsh sent us funds through money orders that were wrapped in cellophane to look like a package of playing cards.

How long did it last?

Until 1962. When the Rocket Crisis occurred in October, the US government cancelled all flights from Cuba.

How many children were taken out of the country?

About 14,000.

How old were they?

All of them under 18 years old.

Did the parents leave with the children?

They were sent out alone.

To relatives?

Most had no relatives in the United States.

Under what protection?

They were placed in foster homes and camps throughout the United States, under the sponsorship of the American Catholic community.

How did the CIA recruit you?

Through Norberto Martinez. Not only me, but also my brother Mongo. This happened in the first weeks of 1962.

Who is this gentleman?

A doctor. He had been the director of the Mazorra hospital in my uncle Grau’s government. He had worked in Pinar del Río during the electoral campaigns. He was married to a relative of Juan Antonio Rubio Padilla, who were like my brothers.

Norberto entered Cuba clandestinely from the United States. He was in trouble. His brother Israel, who was in prison and left recently, told me about Norberto’s presence and the need to hide him. And I hid him.

In what place?

In the back of the house, where Mongo had the dairy business. In that place we had silverware and other valuable belongings that my friends left behind when they left Cuba to be kept until the Revolution fell.

Was Norberto’s mission successful?

It failed. They arrested two of his companions and occupied the weapons they had brought into the country. Then we took him out clandestinely.

What activities did the CIA entrust him with?

To send information.

What kind of information?

All kinds. Especially military and economic. For example, if Cuba bought some buses from England, we would tell the Americans and they would prevent the sale of spare parts.

POLA GRAU AND HER BROTHER RAMÓN, BOTH AGENTS OF THE CIA.

POLA GRAU AND HER BROTHER RAMÓN, BOTH AGENTS OF THE CIA.

Did you work alone?

I created a network of women in most provinces that collected information. We also hid hunted people, gave them asylum, collected money and transported them in a van. Some did not know of my existence. Much less that I was the boss. I handled myself with the necessary discretion.

Do you remember any names?

Queta Meoqui, María Dolores Núñez, a lady named Aurelia, over the years I have forgotten her last name. A good friend of mine. She was the wife of a real senator from Camagüey. As well as Mario del Cañal.

The person I trusted the most was Maria Horta. She was able to leave the country. I don’t know why State Security didn’t arrest her. When I fell prey, she was here, but she left in a quiet plane. However, other women who were not so important fell.

I recognize that Security is one of the best organized things the government has, but they had a failure there. They didn’t catch the woman who was precisely the key.

Has it ever occurred to you that State Security has intentionally let Maria Horta go?

I never thought about it.

By what name were you known?

My old friends used to call me Polita. The others, Hilda or Isabel.

Did you think that the Americans would achieve their freedom?

At first, yes. Then I became disappointed in them. We served them so well and none of us were taken away.

Were they ungrateful?

I’m sure they were. Although they said that we worked at our own risk.

Did you intervene in the preparation of Fidel Castro’s assassination?

They were instructions I received from the CIA.

How would the attack be carried out?

By poisoning with some aspirin-type pills that they sent me from Miami.

How did they reach you?

Tony Varona sent them to me with Leon Curbelo.

What were they for?

In an ordinary Bayer aspirin knob.

What color were they?

White.

What did he do with them?

I gave the knob to Herminia Suárez to keep it.

Why to her?

Her house was the one that served as contact with the Rescue people and with the group of Carlos Guerrero, an old friend of mine.

What did she do with the “aspirins”?

Cruz, Margolles and I agreed to distribute them among collaborators we had in the gastronomic network. Not much time had passed when a diplomatic friend asked to see me.

From which embassy?

Spain.

What was his name?

Alejandro Vergara.

What did he want?

He gave me a letter from Tony Varona and some capsules sent to me by the CIA.

What did the letter say?

He explained that these capsules were more effective for Castro’s assassination and how to use them.

What did they contain?

A deadly poison prepared in the CIA laboratories. They were flavorless liquid capsules. They had an effect on the body between 12 and 24 hours after being swallowed, and they left no trace.

How did you distribute them?

I gave several to Manuel de Jesús Campanioni, who had been a dealer at the San Souci cabaret, and he distributed them to gastronomic workers he trusted.

We were fascinated by the capsules. When we saw that time was passing and nothing was happening, someone – I think it was Matamoros – thought that we could also try to poison some leader, a “peje gordo”, so that Castro would go to the funeral and make an attempt on him. We had people and weapons to carry out the action. We requested authorization from the CIA to apply this variant. They answered in the affirmative.

With this intention, I took a capsule to a young man who worked in the El Recodo cafeteria. But I did not find it. The boy had left the country.

In the midst of all this, Margolles was arrested. They put him on trial and shot him. He was the soul of Rescate. Cruz was the coordinator but the man of action, the military man, was Margolles, and when he died, everything fell apart.

What did he do with the capsules?

I also gave them to Herminia Suárez to hide them in her residence. Until Dr. Carlos Guerrero asked me for them.

What was the final destination of the capsules?

In those years I was working in the cafeteria of the Habana Libre Hotel, one of the places Castro used to visit, a clerk called Santos de la Caridad Pérez Núñez, who received from Campanioni two capsules with the precise instructions to use them against the Prime Minister.

Where did Pérez Núñez take them?

He kept them in his employee locker at the hotel. Later he placed one in the ice cream fridge in the cafeteria.

Where in the fridge?

Inside the middle door, between some tubes that serve as a conduit for Freon gas.

What happened?

One night in March 1963, Castro arrived at the cafeteria. As was his custom, he asked for a chocolate shake. Santos de la Caridad was working. He went to the freezer to get the capsule and pour it into Castro’s shake.

When he went to remove the capsule, the one that had stuck to the cold, burst. When they told me that for me it was a real miracle. I don’t know if I should talk about this. I’ve never discussed it with anyone.

What haven’t you told anyone?

Well, we had studied all the variations for years. The CIA had even analyzed any unforeseen event. But no one, absolutely no one, thought that the capsule would harden in the cold and that it would burst when you took it.

What I am about to tell you does not diminish the professionalism with which Cuban security worked against us. It is not because I have been defeated that I am now going to deny my enemies.

In prison I learned of other cases, of other attempts at assassination attempts that also failed, sometimes even because of changes in timetables, because of insignificance, because of inspirations from Castro himself that no one has ever been able to explain. Apparently, providence is on his side.

The Theory of Induced Demoralization

DESDE LA IZQUIERDA

The Theory of Induced Demoralization

Combating induced demoralization in no way means suspending criticism. Quite the contrary. It implies the exercise of responsible and well-founded criticism, which safeguards unity and does not make it easy for the enemy to destroy us. Demoralized we are nothing

Author: Fernando Buen Abad | internet@granma.cu

December 20, 2020 20:12:21

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

2020: Hollywood’s worst year

2020, the worst year for Hollywood and theaters

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Photo: Internet

With only a few days to go before 2020 becomes a historical reference, what many had been predicting is being confirmed: theaters in the United States had the worst box office results since 1980, the year in which the calculation of the collections began.

But if you look back at inflation and other indexes moviesof the economy, you can be sure that 2020 has been the most chaotic year, not only for U.S. movie houses, but in the history of the Hollywood film industry, the most powerful in the world.

Losses from the pandemic have been in the millions, and according to the Hollywood Reporter, box office receipts in 2020 represent an 80% drop in revenue from 2019.

If the damage was not greater, it is because US cinemas were able to function fully until mid-March, but since then they have been intermittent, with few spectators and essential isolation, while in territories like California and New York the policy of closed doors was maintained.

Also, the box office in Asian countries that exhibited films produced in Hollywood contributed to the fact that the collapse was not total, as well as the films released in streaming, an option before which some production houses have remained hesitant, waiting for the vaccines against covid-19 to end up recovering the luminous paths of the great cinematographic business.

But time is running out, capitals are contracting, and there is no lack of studios like Warner Bros. who have already announced that they will not wait for the movie theaters and will play films in 2021 by releasing them in streaming, ignoring the movie theater owners who, standing at the entrance of their theaters, continue to shout and talk about betrayal.

Houdini and Doyle

Houdini and Doyle

Among the criminal and detective series to which Multivision has accustomed us at night, a rare advert snuck in: Houdini & Doyle

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Photo: Internet

Among the crime and detective series to which Multivision has accustomed us at night, a rare advert has crept in: Houdini & Doyle. What did the famous escapist, precursor of David Copperfield’s truculence, have to do with the creator of Sherlock Holmes? How much truth and how much imagination is there in the approach to the cases developed throughout the ten chapters conceived by David Shore, Dr. House’s own, in the service of the 2016 British-Canadian co-production?

The truth was that, in real life, Harry Houdini (Budapest, 1874-Detroit, 1926) and Arthur Conan Doyle (Edinburgh, 1859-Crowborough, 1930), met, dealt with and made enemies. The bond and the antagonism had a certain basis. The writer who applied with tenacity and contumacity the deductive method became fanatical about occultism. meanwhile, the magician who made an epoch in Europe and the United States by untying chains, overcoming immersions and weaving optical illusions, disbelieved in spiritualism and appealed to reason to explain complex phenomena. So much so that he publicly denounced the medium who sold him an alleged message sent by his mother from the beyond: the text, headed by a Christian cross, was written in impeccable English. The magician’s mother was ignorant of that language, spoke in Yiddish, and professed Judaism.

Again and again, in each chapter of the series, the two confront each other in the effort to decipher mysteries and misunderstandings come to light. There is no progression in their views, for when Doyle (Stephen Mangan) seems to fail, and Houdini (Michael Weston) is stubborn, the case is solved by plausible, though sophisticated, explanations that leave a margin of doubt for Houdini to admit the possibility of supernatural intervention, and Doyle, more defeated than convinced, becomes more like Holmes than himself.

Shore and the Canadian scriptwriter David Titcher, known among us for the series The Librarians, got their hands on a third character, Detective Stratton (Rebecca Liddiard), the first woman with that degree in the English police force, a fact that was never sufficiently taken advantage of -it would have been an interesting feminist note- and ended up paling in the face of the antagonists’ clashes.

Neither by polishing the epochal reconstruction to the last detail, nor by mixing ingredients from the gothic novel and the psychological thriller, nor by putting into the plot, to the cannon, real characters, such as the inventor Thomas Alva Edison and Bram Stoker, the creator of Dracula, managed to hold the artistic breath of the series, which was canceled at the end of the first and only season. Critics recalled the counterpoint between Houdini and Doyle as a washed-up version of the debates between Mulder and Scully in the X-Files.

The Bravery of the Bravos

The Bravery of the Bravos

The event was chaired by Bruno Rodríguez Parrilla, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Cuba (Minrex), and Alpidio Alonso Grau, Minister of Culture (Mincult), who personally presented the award.

Author: Pedro de la Hoz | pedro@granma.cu

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Photo: Ariel Ley Royero/ACN

If bravery is a quality to face each step in life with courage, it is abundant in the political and artistic career of Estela and Ernesto Bravo. She, a North American, he, an Argentine, supportive, internationalists and Cubans by conviction since they decided to share dreams and destiny in the homeland of Marti and Fidel.

The Distinction for National Culture awarded to both of them last Saturday honors their passionate contributions to art and their permanent commitment to the ethical values and ideals of justice advocated by revolutionary Cuba.

Culture Minister Alpidio Alonso presented the award to the Bravo couple in a ceremony attended by Bruno Rodríguez Parrilla, a member of the Party’s Political Bureau and Minister of Foreign Affairs, during which the poet Nancy Morejón gave the words of praise.

Estela’s contribution to the documentary screen as a director, always assisted by Ernesto as a scriptwriter, consultant and coordinator in the tasks of production, stands out among the most lucid and penetrating in the cinema of the last four decades, starting with the 1980 release of Los que se fueron [Those Who Left].

With a catalog of more than 30 works of diverse footage, a substantial part of the Bravos’ filmography bears witness to events related to Cuban migration to the United States and the traumatic human and family cost of the hostility of that country’s rulers towards Cuba.

It is worth looking at the Latin American and Caribbean context of the time of the dictatorships and the US interventions in the region.

But, without a doubt, the most endearing productions of Estela and Ernesto are those that have had the historic leader of the Cuban Revolution in the forefront. Fidel, the untold story is revealed as one of the most complete portraits of the Commander in Chief’s personality.

MAS Strengthens its Majority

MAS Strengthens its Majority in Bolivian Parliament

The second Bolivian political force will be the Citizens’ Community Alliance, of former President Carlos Mesa.

By Redacción Digital | internet@granma.cu

October 24, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Photo: Taken from the Internet

With 97 percent of the officially counted election records, the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) consolidated its majority in the Bolivian Legislative Assembly on Friday, reported Telesur, by securing 21 senators and 78 deputies.

The Plurinational Electoral Body (OEP) of Bolivia reported this Thursday that the MAS, of President-elect Luis Arce, obtained 78 of the 130 seats in the Chamber of Deputies, while in the Senate it obtained 21 of the 36 seats.

The Citizen Community Alliance (CC), of former president Carlos Mesa, obtained 35 deputies and 11 senators, to become the second political force of the South American country.

Meanwhile, the Creemos movement, led by former presidential candidate Luis Fernando Camacho, will have four legislators in the upper house and 17 deputies.

With this composition, the Movement Towards Socialism will be able to approve laws and make parliamentary decisions, without having to build political alliances with the opposition.

However, it will have to build agreements with CC and Creemos to designate authorities, approve judgments of responsibilities and even propose constitutional changes, since this requires the approval of two thirds of the Legislative Assembly.

Among those who must be appointed with a two-thirds majority are the ombudsman, the attorney general and the comptroller general.

This Friday, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) officially declared Luis Arce, of MAS, to be the president-elect, who obtained 55.10 percent of the valid votes cast in the general elections of 18 October.

In second place was Comunidad Ciudadana, with 28.92 percent; and in third place, Creemos with 13.82 percent of the votes.

Robert Mapplethorpe’s Orchids

Robert Mapplethorpe’s “Orchids”

Our sexuality, no matter what, can only be judged in its beauty, by our own way of assuming it respecting the other.

By Ernesto Estévez Rams | internet@granma.cu

September 13, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Photo: Robert Mapplethorpe

For all the scandal they caused, in life and in death, Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs, his collection of orchid and lily photos would pass, on a first reading, as almost virgin works. They are not.

Mapplethorpe was a New York photographer who died in 1989 of AIDS. By the time of his death, his photographic work was famous, particularly the black-and-white portraits he took of famous people, including a few Hollywood celebrities, throughout his career.

Robert was a homosexual, a condition which, far from being hidden, he incorporated into his work, to the shock of censorship and to the extent of provoking notoriety. But to say it that way does not do justice to the place the photographer gave to sexuality in his life. Exploring what he considered the individual limits of erotic pleasure, Robert not only exposed his sexuality at its fullest, but also vindicated the dominance that each person should exercise over it to the extent of their own fulfillment.

In an interview with Vanity Fair, when AIDS was already advanced, he summarized the meaning of his most sexually explicit photos, saying that forcing people to do things they don’t want to do is not erotic. Consistency also implied the daring to look beyond the conventional, as long as it was “people looking for a simultaneous orgasm.”

Mapplerthorpe’s work is a continuous cry of an unsuccessful search of the self, in the images that he managed to capture of others. In that sense, through some of his photos, the spectator transforms his condition of observer to that of observed. What happens in all of them is that it is almost impossible not to react to them. In many cases, it makes our subconscious uncomfortable, as it accepts beautifully what the indoctrinated conscious insists on rejecting. A colleague photographer, anonymously, confessed to a chronicler that Robert’s erotic work would not have been acceptable if it had been about heterosexual relationships. He is probably right, such is the prejudice.

The Perfect Moment collection, which displayed explicit photos of high sexual content (of all kinds), was censored as pornography by the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington. The controversy reached such prominence that even members of the U.S. Congress spoke out about the use of public funds to promote art. In 1990, the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati was sued for the exhibition of the collection, which was labeled obscene. The gallery was acquitted, along with its director Dennis Barrie. This was the first time that an art gallery was sued for the contents of an exhibition.

In 1998, a book displaying the Mapplethorpe photos was confiscated by the police in England. A University of Central England student, writing a thesis, took the text to a local store to have copies made of some photographs. The shopkeeper, alarmed by the photos he saw, called the police, who did not believe to was art. The university was required, as a condition for the return of the book, that certain pages of the book be hidden. After six months of back and forth, the book was finally returned without censorship.

The well-known writer, musician and playwright Patti Smith was a Mapplethorpe partner , whom she met in a bookstore in the mid-1960s. The relationship was as deep as it was torrid because, by that time, Robert was still dealing with his sexual identity. Despite their separation as a couple, they remained friends all their lives, and she called him one of the most important people in her life.

In 1969, Patty and Robert moved to the Chelsea Hotel, next door to the El Quijote restaurant. As Craig Brown describesit, when Patti entered the restaurant, “the scene was absurdly typical of the era, with musicians and bottles of tequila scattered in equal proportions. Jimi Hendrix is there with a large sombrero, perched on a table at the end. To his right, Grace Slick and the rest of Jefferson Airplane, sitting around another table. To his left, Janis Joplins in a conspiracy with her musicians”.

It was Bobby Neuwirth, a friend of Bob Dylan’s, who introduced Patti to Janis. He told the singer, “This is the poet Patti Smith. From that moment until Joplins’ death, she called her friend, the poet.

From Porgy and Bess is the famous Summertime aria, whose lyrics are by DuBose Heyward and music by George Gershwin. They were taken out of the original opera, and performed by the most diverse artists over the years. There are said to be more than 25,000 recordings of the song, beginning with its first commercial success in 1936, in the voice of Billie Holiday.

Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong have their version of Summertime, with a memorable trumpet introduction, followed by the irruption of Ella’s voice alternating with Louis’. Can it get any better? Perhaps not, but in 1976 Ray Charles performed it with Cleo Laine at a transcendent height, and Miles Davis (ah, Miles) played it in an instrumental version that was true to his Midas status: everything he played he turned into jazz.

In another vein, Peter Gabriel, with a captivating harmonica introduction by Larry Adler, gave us a Summertime with a guttural voice to break us like a pencil, and Sting, in 1991, did his thing with the Dutch orchestra of the 21st century.

But, in spite of all the excellence of those interpretations, I am left, if I have to choose, with the incomparable Janis Joplin, the voice of several generations who came with the flower boy and opposition to the Vietnam War, along with the breaking of the sexual norms of the 1960s.

How beautiful you are Janis. / You sang as if they were confessions. / It doesn’t matter if the songs were of others, / you made them a testimony of your sins.

Janis Joplin was born in Texas in 1943 and was abused by other students at school as a freak. She was obese and had very bad acne, and was yelled at for doing horrible things, including racially-motivated offenses for getting along with Black people. Her shelters were reading, painting and music. While at the University of Texas, the campus newspaper referred to her as a brave woman, unafraid to distinguish herself from others by the way she dressed, contrary to the conventions of the time, her love of music and her habit of going barefoot.

No one managed the discursive capacity of the scream as she did, / no one managed the body language as she did, / hers was the method brought to the song. The James Dean / of that world she assumed until she broke it / like him: at the wheel of different cars. / All that and more happened before the crows descended / and turned the whole landscape into a firework display.

On one occasion, Janis was crying inconsolably, because a flirt of the night had left with another woman. Dressed in magenta and pink, wearing a kind of scarf with purple feathers, depressed by her failure, she said to Pattyi, “This always happens to me, partner. Another lonely night”. Patti accompanies Janis to her room and listens to her tell of her unhappiness over and over again. As a consolation, Patti confesses that she has written a song for her and sings it to her to encourage her. In an explosion of depressed joy, Janis jumps from the song “That’s My Song,” she screams, as she arranges her scarf in front of the mirror. Two months later she was dying of a drug overdose.

I don’t know if Robert Mapplethorpe ever photographed Janis Joplin directly, but I can’t wait to see her in the magenta, pink and purple orchids that I can guess behind her photos, even in the gray ones. The photographer’s orchids transcend innocence to become what is perhaps his most aggressive break.

Far from the shocking direct message against conventionality, those photos where the flowers end up being pure eroticism. They express a transcendent, and in a certain way fulminating, apprehension of something beautifully ungraspable. They shout to us that our sexuality, no matter what, can only be judged in its beauty, by our own way of assuming it respecting the other.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||

You must be logged in to post a comment.