Ricardo Alarcón 7

Amuchastegui: Political News in Cuba

- English

- Español

POLITICAL NEWS IN CUBA

By Domingo Amuchastegui

May 5, 2022

Received by email from the author

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

After May Day in Cuba, it is convenient to point out some very important issues.

Following the social outburst of July 11, 2021 originated by the sustained intolerance and gross negligence in the management of the Party-State, the effects of the economic war applied by the Trump administration (maintained until today by the Biden administration) and the devastating consequences of two years of pandemic, the image of stability and legitimacy of the experience of the Cuban Revolution suffered its most important setback after several episodes of negative signs that pointed in that direction (Mariel, Maleconazo and Balseros in the first place). There was an abundance of critical judgments and attacks on the police violence deployed, the trials of those arrested and the sentences handed down.

The worst prognoses abounded and more than a few doubted the capacity of the Party-State to reestablish its stability and legitimacy. Many questioned its ability to rally broad masses of the population behind it and whether it would be able to masses of the population and whether it would be able to do so on May Day, the effects of the pandemic attenuated.

The mass turnout that the Cuban leadership was able to mobilize on this May Day both in the capital of the country and in all the provincial capitals. There were not thousands or tens of thousands, but hundreds of thousands throughout the country. Carried? Obliged? Only unconditional supporters of the “regime?

Such formulations fall more than short. This mass demonstration, of the broadest popular sectors, overthrer the worst prognoses, neutralized the worst forecasts, neutralizee to a considerable extent the negative effects of 11J [July 11], to a large extent restored the image of stability and legitimacy. Of course, none of this in any way diminishes the tensions and grievances existing today in Cuban society. Instead of congratulating the Cuban leaders for the success of the mobilization, what happened on May Day should summon them with more urgency and comprehensiveness to the reforms and solutions that the whole country has been demanding.

To attend or not? The Summit of the Americas to be held in early June in the U.S. presents a serious problem created by the Biden administration. As organizers of the event, Washington is determined to exclude three countries: Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua. Biden seeks a disciplined and obedient conference, without voices that raise problems and positions discordant with his administration’s objectives on many issues. There is no desire to hear arguments against the embargo (blockade) or the hemispheric and international legitimacy of these countries and other hot-button issues such as migration, trade and investment and the hypothesis of a single currency for South America and the Caribbean.

The worst-case scenario in terms of confrontation would be the case of Cuba, excluded for many years, but whose admission has been was recognized by the Obama administration (of which Biden himself was the vice-president and not even questioned by the Trump administration. So why are Biden and his team taking this position? Perhaps with the delusional idea of winning the Cuban and Latino vote in Florida, and thus securing his impossible re-election?

Recently, Mexico’s President Lopez Obrador has emphasized a cardinal reasoning with respect to this possible exclusion: “If they are not (countries) of the Americas, what galaxy are they from?” The trajectories of brutal repression and political assassinations in not a few countries of the hemisphere in recent years would seem to be no reason to exclude them. Then there is the wave of electoral victories of forces described as “leftist” and of stability and legitimacy, although none of this in any way diminishes the tensions and grievances existing today in Cuban society. Instead of congratulating the Cuban leaders for the success of the mobilization, what happened on May Day should summon them with more urgency and urgency and comprehensiveness to the reforms and solutions that the whole country has been demanding.

To attend or not? The Summit of the Americas to be held in early June in the U.S. presents a serious problem created by the Biden administration. As organizers, Washington is determined to exclude three countries: Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua. Biden seeks a disciplined and obedient conference, without voices that raise problems and positions out of sync with his administration’s objectives on many issues. There is no desire to hear arguments against the embargo (blockade) or the hemispheric and international legitimacy of these countries and other hot-button issues such as migration, trade and investment and the hypothesis of a single currency for South America and the Caribbean.

The worst-case scenario in terms of confrontation would be the case of Cuba, excluded for many years, but whose admission was recognized by the Obama administration (of which Biden himself was the vice-president) and not even questioned by the Trump administration. So why are Biden and his team taking this position? Perhaps with the delusional idea of winning the Cuban and Latino vote in Florida, and thus securing his impossible re-election?

Recently, Mexico’s President Lopez Obrador emphasized a cardinal reasoning with respect to this possible exclusion: “If they are not (countries) of the Americas, what galaxy are they from?” The trajectories of brutal repression and political assassinations in not a few countries of the hemisphere in recent years would seem to be no reason to exclude them, nor would the wave of electoral victories of forces of a left described as “leftist” and forces described as “pink” by many media and specialists, as well by specialists of a similar inclination, strengthen the growing of opposition to Biden’s policies and actions from the Mexican border to border from Mexico to Santiago de Chile and Buenos Aires.

With strength, the CELAC (Conference of Latin American and Caribbean States) and the Puebla Group (comprised of a major group of Latin American and Caribbean (made up of an important group of parties and personalities) have clearly pronounced themselves against against such exclusionary maneuvers. The three “bad guys” (Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua), for their part, have strongly denounced this US maneuver.

So what will the Biden administration do to ensure that this conference will represent the Americas as a whole, without exclusion or discrimination? We will soon see the consequences of such an action, which is totally inappropriate.

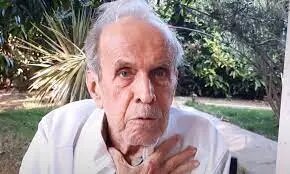

Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada passes away

His political and intellectual stature, his modesty and honesty in all aspects, made him worthy of the admiration and respect of all his comrades and of his people, since the times of the people, from the times of the clandestine struggle against Batista’s tyranny, to the internal struggles to the internal struggles within the M-26-7 and the University of Havana, his enlightening speeches in the panels of the People’s University, in his long years in the his long years at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MINREX), both as brilliant director as well as brilliant ambassador to the UN, vice-minister and minister. His presentations, his brilliant participation in negotiations and conflicts, were always brilliant until his his promotion to the Political Bureau and to the presidency of the National Assembly with the same trajectory.

The official media in Cuba (press, radio and TV) and even beyond (El País of Spain, Eurovision and others) highlighted his work. Spain, Eurovision and others) also highlighted the news of his death and of his political and diplomatic and of his political and diplomatic performance.

Undoubtedly, an extraordinary man. And if he was – as everyone acknowledges – one must ask why he was why he was inexplicably and abruptly removed from all his positions. No explanation was given to his people; to anyone. He disappeared from the public public scene and never again held a position in the Party or Government. Nothing. What cardinal sins did he incur to mistreat him in this way, almost at the end of his life? No one can explain it; no one can justify it. It remained as one more mystery at the highest levels of power. It is not the only case of of such unjustifiable behavior.

Let us hope that when Leopoldo Cintra Frías (former minister of the FAR and the officer with the most internationalist actions accomplished) or Abelardo Colomé Ibarra (Minister of the Interior) pass away. Ibarra (Minister of the Interior), both members of the Politburo, both Heroes of the Republic and both disappeared from the political scene without an explanation. In what monumental errors did they incur to become Non-Persons? Corruption, nepotism, disloyalty, political differences? Those who admired and respected them for decades deserve a valid explanation.

ACTUALIDAD POLITICA EN CUBA

Por Domingo Amuchastegui

(5/5/2022)

Pasado el Primero de Mayo en Cuba, conviene puntualizar algunas cuestiones de mucha importancia.

A raiz del estallido social del 11 de Julio del 2021 originado por la sostenida intolerancia y mayúsculas negligencias en la gestión del Partido-Estado, los efectos de la guerra económica aplicada por la administración Trump (mantenida hasta hoy por la administración Biden) y las consecuencias devastadoras de dos años de pandemia, la imagen de estabilidad y legitimidad de la experiencia de la Revolución Cubana sufrió su más importante revés después de varios episodios de signo negativo que apuntaban en esa dirección (Mariel, Maleconazo y Balseros en primer lugar). Abundaron los juicios críticos y ataques a la violencia policíaca desplegada, los juicios a los arrestados y a las condenas aplicadas.

Los peores pronósticos abundaban y no pocos dudaban de la capacidad del Partido-Estado para restablecer su estabilidad y legitimidad. Muchos se cuestionaban la capacidad del mismo para convocar en su apoyo a amplias masas de la población y si sería capaz de hacer esto el Primero de Mayo, atenuados los efectos de la pandemia.

El baño de masas del que fue capaz de articular la dirigencia cubana este Primero de Mayo tanto en la capital del país como en todas las cabeceras provinciales. No fueron miles o decenas de miles, sino cientos de miles a lo largo y ancho delpaís. ¿Acarreados? ¿Obligados? ¿Sólo incondicionales del “régimen?

Semejantes formulaciones se quedan más que cortas. La demostración de masas, de amplísimos sectores populares, echan por tierra los peores pronósticos, neutralizan en medida considerable los efectos negativos del 11J, en buena medida restablecen la imagen de estabilidad y legitimidad, aunque nada de esto en nada disminuye las tensiones y reclamos existentes hoy en la sociedad cubana. En lugar de congratularse los dirigentes cubano por el exitazo movilizativo, lo sucedido el Primero de Mayo debe convocarlos con mayor urgencia e integralidad a las reformas y soluciones que la totalidad del país viene reclamando.

¿Asistir o no? La Cumbre de las Américas a celebrarse a comienzos de junio en EEUU presenta un serio problema creado por la administración Biden. Como organizadores de la misma, Washington se empeña en excluir de la misma a tres países: Cuba, Venezuela y Nicaragua. Biden busca una conferencia disciplinada y obediente, sin voces que planteen problemas y posiciones discordantes con los objetivos de su administración con respecto a no pocos temas cruciales. No se desea escuchar argumentos contra el embargo (bloqueo) o la legitimidad hemisférica e internacional de estos países y otros temas candentes como las migraciones, comercio e inversiones y la hipótesis de una moneda única para Suramérica y el Caribe.

El peor de los casos en materia de confrontación sería el caso de Cuba, excluída durante largos años, pero reconocida su admisión por la administración Obama (de la cual era vicepresidente el mismísimo Biden) y no cuestionada ni siquiera por la administración Trump. Entonces, ¿por qué Biden y su equipo asumen esta posición? ¿Tal vez con la ilusa idea de ganar el voto cubano y latino de la Florida y con ello asegurarse su imposible reelección?

Recientemente, el presidente de México, López Obrador, ha enfatizado un razonamiento cardinal con respecto a esta posible exclusión: “Si no son (países) de las Américas, ¿de qué galaxia son?” Las trayectorias de brutales represiones y asesinatos políticos en no pocos países del hemisferio en estos últimos años parecen no ser razón para excluirlos; la oleada de victorias electorales de fuerzas de una izquierda calificada de “rosada” por muchos medios y especialistas asi como las venideras victorias de similar inclinación, fortalecen el creciente bloque contestario a las políticas y acciones de Biden desde la frontera de México hasta Santiago de Chile y Buenos Aires.

Con fuerza, la CELAC (Conferencia de Estados de América Latina y el Caribe) y el Grupo de Puebla (compuesto por un importante grupo de partidos y personalidades) se han pronunciado claramente contra tales maniobras de exclusión. Los tres “malos de la película” (Cuba, Venezuela y Nicaragua) por su parte han denunciado con fuerza esta maniobra de EEUU.

¿Qué hará entonces la administración Biden para que esta conferencia represente a la totalidad de las Américas, sin exclusiones ni discriminaciones? Veremos muy pronto y las consecuencias de semejante acción, del todo improcedente.

Fallece Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada

Su estatura política e intelectual, su modestia y honradez en todos los órdenes, lo hizo acreedor de la admiración y respeto de todos sus compañeros y de su pueblo, desde los tiempos de la lucha clandestina contra la tiranía de Batista hasta las luchas intestinas dentro del M-26-7 y en la Universidad de La Habana, sus esclarecedoras intervenciones en los paneles de la Universidad Popular, en su largos años en el Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores (MINREX), tanto como director como brilante embajador en la ONU, vice-ministro y ministro. Sus presentaciones, su brillante participación en negociaciones y conflictos, fueron siempre brillantes hasta su promoción al Buró Político y a la presidencia de la Asamblea Nacional con idéntica trayectoria.

Los medios oficiales en Cuba (prensa, radio y TV) e incluso más allá (El País de España, Eurovisión y otros) destacaron igualmente la noticia de su fallecimiento y de su ejecutoria política y diplomática.

Sin dudas, un hombre extrardinario. Y si así fue -como todos reconocen- hay que preguntarse porqué fue, inexplicable y bruscamente, destituído de todos sus cargos. No se le dio una explicación a su pueblo; a nadie. Desapareció de la escena pública y jamás volvió a ocupar un cargo en el Partido o Gobierno. Nada más injusto. ¿En qué pecados capitales incurrió para maltratarlo de esa manera, casi al final de su vida? Nadie se lo explica; nadie lo justifica. Quedó como un misterio más en las máximas instancias del poder. No es el único caso de semejante proceder injustificable.

Esperemos que cuando fallezcan Leopoldo Cintra Frías (ex-ministro de las FAR y el oficial con más acciones internacionalistas cumplidas) o Abelardo Colomé Ibarra (Ministro del Interior), ambos miembros del Buró Político, los dos Héroes de la República y ambos desaparecidos de la escena política sin una explicación, se aclaren el por qué de semejantes acciones. ¿En qué monumentales errores incurrieron para convertirse en No-Personas? ¿Corrupción, nepotismo, deslealtad, discrepancias? Los que los admiraron y respetaron durante décadas merecen una explicación válida.

Ricardo, my unforgettable friend

Ricardo, my unforgettable friend

By Max Lesnik

May 3, 3033

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

“You look Death in the face”, Ricardo Alarcón once told me on one occasion, at a time when we were both in grave danger, in the face of an attack by the Batista police in the midst of a student riot, descending the university steps with the leader of the FEU, José Antonio Echevarría.

And that is how Ricardo Alarcon left the world of humans, looking death in the face, to enter the altar of the Cuban homeland as a worthy revolutionary of Mambisa lineage, for the “De Quesada”, an independentista family that has left only glories and sacrifices and never unworthy betrayals.

I did not have the opportunity to give a final embrace to my dear friend who had in me the affection of a brother as Alfredo Guevara, Eusebio Leal, Jesús Montané and Manuel Piñeiro Losada were in life, all of them deeply Martiano and Fidelista until the last breath of their fruitful existences.

When I arrived in Havana last Thursday, April 28, Ricardo was already in a very serious condition. I was unable to give him a goodbye hug. His daughter Margarita -whom I love as one of my daughters- told me with sorrow that Ricardo was already in a death trance, the man who said like Marti “that death is not true when the work of life is fulfilled”.

His daughter Margarita and his grandson Ricardito, my godson by baptism, who in spite of his short years already has the vigor and the natural intelligence of the grandfather who was gone, who saw in him, as the prolongation of his existence on earth, are left.

His fruitful diplomatic career as Cuba’s delegate to the United Nations, of whom it was said at the time that he was the most brilliant ambassador of the multitudinous international forum of the UN at the time, as well as in Cuba, his very skilful presidency for more than two decades of the Cuban Parliament, also remain for history. of the Cuban Parliament.

One of the greats of the “Centennial Generation” has died. A devoted Martiano and faithful Fidelista. For me, he will always be simply “Ricardo”, my unforgettable friend.

In honor of my friend Ricardo

IN HONOR OF MY FRIEND RICARDO

by Carlos Alzugaray

May 1, 2022

Ricardo Alarcón

Translated by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

I will never forget his simplicity and modesty. He was a thorough revolutionary, a patriot without blemish, a brilliant diplomat and a politician from another galaxy.

I met Ricardo Alarcón in 1963. I was 20 years old and a young country specialist in MINREX when Raul Roa, our Chancellor of Dignity, recruited a group of FEU leaders who had finished their studies after the triumph of the Revolution due to the closure of the University, to join the Foreign Ministry in different positions. Ricardo entered as Director of Latin America and the Caribbean, but very soon that Directorate merged with the United States and Canada, which was where I worked.

He immediately established a fraternal relationship with the motley group of young and not-so-young people who became his subordinates. As a boss, he was not difficult to get along with. He listened to anyone who had something to say to him. When he had to talk to someone, he didn’t usually call them into his office, he usually went to the workstation of his subordinates and asked what he had to ask right there. He was not satisfied with simple, stereotyped answers. And, very importantly, when a decision had to be made, he would hold large meetings with all of us who could contribute something to the issue in question. Like Roa, he was an enemy of all manifestations of bureaucratism.

I must confess that a very close relationship was established between us, both professionally and personally. Probably because we were both passionate about studying and analyzing American politics. We were and were consciously anti-imperialist, but when we sat down to talk about the United States and its foreign policy we did not do so with stereotypes or slogans.

Ricardo knew how to make constructive criticisms and did not mind at all if you went against him. This made us feel very comfortable working with him.

One thing that impressed me a lot was his simplicity and modesty. Ricardo was not interested in anything material, except a good book and a good cigar. In those early years, even though as Director he would have been assigned a car, he never bothered about it. He would come and go on foot from his home at 21 between N and W. Early in the mornings he would be seen entering the Calzada gate of MINREX with a briefcase full of papers under his arm. Many times when the work was finished he had to be given a bottle.

In 1965 our paths separated and we met again in the late 1970s when he returned from his first mission as Ambassador to the UN and assumed the post of Vice Minister in charge of America. From those times I remember our exchanges on American politics. Although he could have the possibility of ordering his lunch from the dining room to eat it in a pantry that was available for the Vice Ministers on the floor they occupied, Ricardo preferred to go down to the dining room and stand in line like everyone else. He would sit down and eat whatever was on the tray and did not mind at all if others sat at the table he occupied. He always enjoyed a good conversation, especially if it was about politics.

Later, in the short time he was Foreign Minister, he asked me to work with him as an Advisor. In 1992, after a large meeting of the Ministry’s Board of Directors, attended by numerous high-ranking officials, it was decided to undertake a task that then seemed impossible: to get the UN General Assembly to approve a Cuban resolution condemning the U.S. blockade against Cuba and demanding its lifting. This resolution had been presented the previous year when Alarcón was Ambassador to the world body but it had to be withdrawn due to the possibility of losing the vote. Ricardo was not very convinced that this could be achieved and that is why he called that meeting to listen to the opinions of all the Directors. After a long debate, he personally gave the go-ahead to the path that a few of us proposed.

When he made the decision to “take the plunge”, Ricardo asked me to coordinate all the actions from the office. This meant that we were in contact with each other every day at all times.

In that battle, which was one of his greatest diplomatic successes, Ricardo deployed an intense activity full of rigor, intelligence and political will. Every day at the end of the day we had a meeting in which we examined how things were going and decisions were made for the following day. Naturally, although it was always late at night, when the meeting was over, I was left to prepare all the instructions for the Ambassadors and Directors. It should be noted that even if it was after midnight, our Embassies, scattered all over the world, could be starting their working day and could not wait. Ricardo would not leave me alone; he always waited for me to finish what he had to do and we would leave the Ministry together. He didn’t need my “bottle” anymore. And, besides, I lived two blocks away.

The Ministry and its Embassies worked together and we achieved what seemed impossible: the General Assembly approved our draft resolution by 59 votes in favor, 3 against and 79 abstentions. I had the pleasure of giving him the news when he was in his office attending to other matters. Although he was surprised and pleased that the vote in favor was so numerous, he immediately began to analyze what we were going to do with it.

It was a concerted effort in which Ricardo demonstrated the ascendancy he had as Minister and the effectiveness of his strategic thinking.

The New York Times (a newspaper that Ricardo read daily when he worked at the UN) described the lead story in its November 25, 1992 edition as follows:

“The General Assembly delivered an unexpected rebuke to the United States today, overwhelmingly passing a resolution that calls for an end to Washington’s 30-year embargo against Cuba.”

One of the first things he did after learning of the outcome was to hold a press conference at the ICC at 23rd and O, and that’s where we went. What was not our surprise when we found out that when the news broke, many people who worked in the surrounding area congregated on that corner, paralyzed the traffic and applauded him deliriously when he got out of the official Lada. Ricardo did not allow himself to be flattered by this. He reacted with his usual modesty and simplicity. He told me: now you sit next to me. It was the most important moment of my diplomatic career and I lived it next to Ricardo and worked with him.

I have some other anecdotes, but I will have to sit down calmly to write them down. For now, I will summarize as follows:

I will never forget his simplicity and modesty. Ricardo was never overburdened by charges. He was a thorough revolutionary, a patriot without blemish, a brilliant diplomat and a politician from another galaxy.

Cubans abroad are part of the Cuban nation

Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada:

Cubans living abroad are part of the Cuban nation

By Esther Barroso Sosa, June 20, 2021/

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

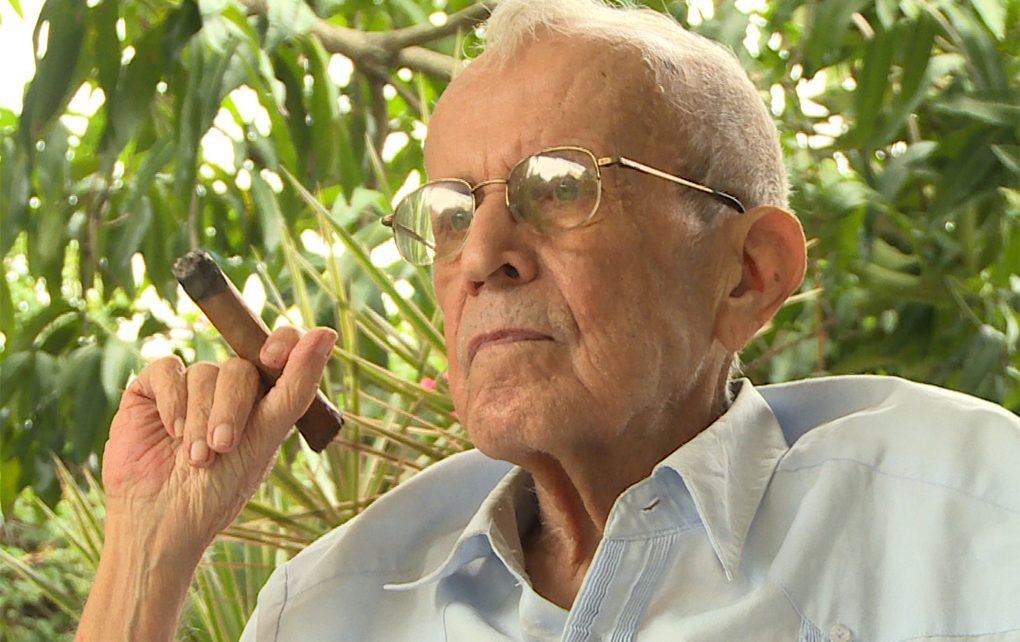

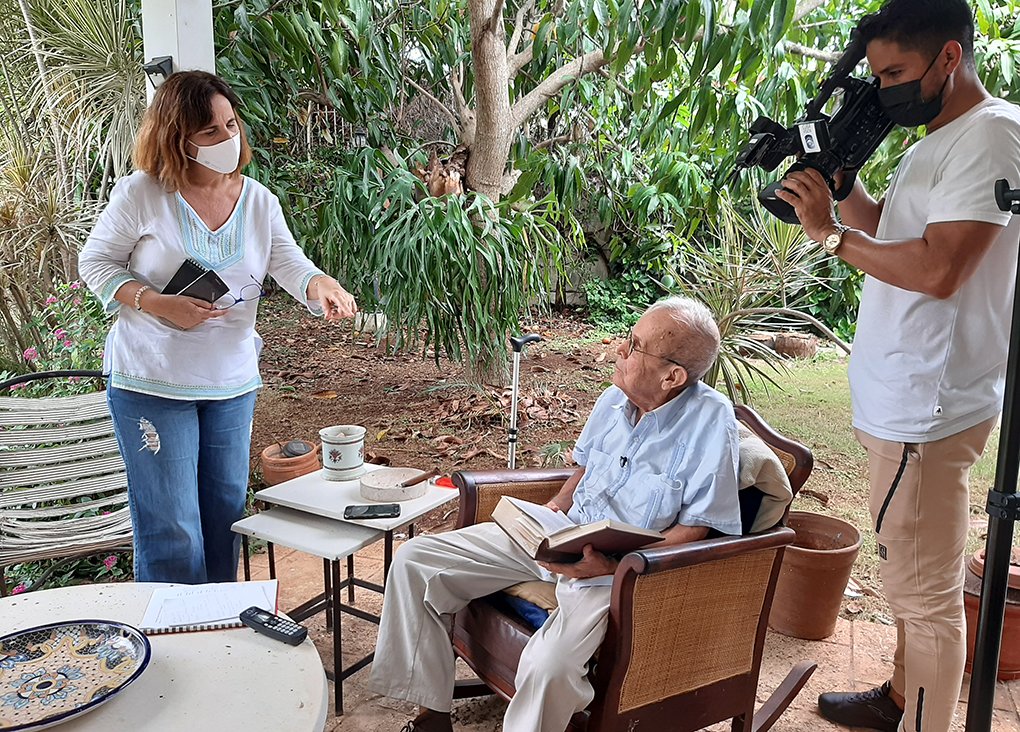

At the age of 84, after having been Cuba’s representative to the UN, Minister of Foreign Affairs and President of Parliament for two decades, among other political functions, he dedicates his days to “things like this”, that is, to giving interviews, such as the one we have asked him to give for the TV series Relatos in(contables), an audiovisual proposal still in the making. Even knowing that the recording has no broadcast date, he has not hesitated to accept.

He lights up a cigar only after the long conversation on a subject he is passionate about is over. And that’s when, at my insistence, he replies, “Yes, I’m writing something about my life, but if I’m going to tell everything I know…” The unfinished answer is probably hotter than the cigar that is already being consumed as we say goodbye. Me, with the promise to publish in full and in print what I have narrated. He, recreating himself with the shapes drawn by the smoke of his cigar.

Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada is a descendant of the family of the second wife of the Father of the Cuban Homeland: Ana de Quesada y Loynaz (1843-1910), who died in Paris, as one more emigrant and after a brief stay in the U.S., where Carlos Manuel de Cespedes sent her, trying to protect her from the rigors of the manigua [jungle] and the threats that were already made against the deposed president of the republic-in-arms.

The nation-emigration issue has not been alien to Alarcón. On the contrary. And not only because his predecessors are scattered around the world, but also because he was one of the promoters of the first dialogue between the Cuban revolutionary government and a representative group of the Cuban community in the United States.

From 1966 to 1978, Alarcón remained in New York as Cuba’s permanent ambassador-representative to the United Nations. From there he witnessed the birth and evolution of initiatives that sought a rapprochement, often critical, with Cuba and its Revolution. Organizations such as Juventud Cubana Socialista, magazines such as Areíto and Joven Cuba, the Institute of Cuban Studies or the Antonio Maceo Brigade -with its impressive first trip to the island at the end of 1977- were some of the antecedents of the Dialogue that would finally be held on November 20 and 21, 1978, after a press conference in September in which Fidel invited representatives of the community to come to the island for that purpose, with the sole condition that no leaders of the counterrevolution or active terrorists would attend.

Seventy-five members of the Cuban community in the United States participated and 140 in a second meeting held on December 8. Alarcón was one of the nine Cuban leaders who, headed by Fidel, made up the representation of the government of the island.

Esther: Shortly before the 1978 Dialogue, you had just returned from the Cuban Mission to the UN. There you had experienced the rapprochement of Cuban emigrants who were interested in being reunited with their country. They had a vision of the Cuban Revolution different from that of the most radical elements of the right-wing of the Cuban community in that country. How did that rapprochement take place, what do you remember of that stage in New York?

Alarcón: The 1978 dialogues with the Community were part of an interesting process of rapprochement. The Antonio Maceo Brigade and other projects arose and everything changed at that time and it will change more and more. It was at the Cuban Mission to the UN, in New York, where it all began. I was the only one at that table who knew almost all the Cuban emigrants who participated in the meeting.

Since I arrived in New York I have had many relationships with Cubans who were living abroad. That is not after the Revolution. You just get there and you discover that lots of Cubans who came to the U.S., many of them illegally, had originally received a B-29 visa, a type of visa that the U.S. gave for visitors, and the classification was with the letter B and for 29 days.

There were many friends that I knew who had arrived for 29 days before 1959 and were still there. It was amazing. They had a strong relationship with the only diplomatic representation Cuba had, because this was before the Interests Section existed. It was logical for them to look for that space. How could a Cuban in New York connect with his family if there were no flights and hardly any communication?

At the same time, there was the Casa de las Americas, which was the continuation of Casa Cuba, dating back to the Revolution of 1930 or earlier, Cubans living in the U.S. who maintained ties with their country of origin and with the Revolution. Little by little, we became closer to them. I used to go to Casa de las Americas a lot, it was the only social place where we could meet Cubans, play dominoes, drink beer. And it was maintained with the contribution of those Cubans.

When you look at their history, there were a lot of them who were B-29s, others were their children. It was a contact center that allowed us to meet a lot of people who, regardless of their ideology, wanted to have a link with their country of origin.

That explains why I was given the task of organizing, inviting and bringing representatives of that community to Cuba, because they were not representatives of something, nobody had elected them, but they were representative of that diversity. We are talking about 1978, almost 20 years after the triumph of the Revolution. There were people who had been changing their point of view. Practically all those who came, I knew them. There were also militant Batista supporters, some of them famous.

Esther: But there was a predominance of young people and especially Cubans who had left very young in the first years after the triumph of the Revolution?

Alarcón: Yes, and for them, it was a challenge. What they were doing was contrary to U.S. government policy. They were emigrants, people residing in a foreign country, so they were in a weak situation. It is logical that among the younger ones there were people willing to take those risks, besides the fact that they had very little connection with the counterrevolution, unlike the older ones.

Esther: There was also a context that favored that: Carter’s position towards Cuba on the one hand and on the other the Cuban government’s willingness to receive them and talk. To what extent did that dialogue come about because of pressure from those Cubans in the U.S. and to what extent did the fact that Fidel and the revolutionary leadership realized that it was necessary to establish that link have an influence? Does what they achieved deserve recognition? What was the driving force behind that dialogue? They had three fundamental objectives that became the three great themes of the Dialogue: that the emigrants be allowed to visit Cuba, family reunification and the release of political prisoners.

Alarcón: Fidel was interested in it being a dialogue with Cubans and not with the U.S. government. Those Cubans achieved, among other things, the visits to Cuba and those permits also depended on the U.S. But the release of the counterrevolutionary prisoners was a unilateral decision of the Cuban government. And it was made, not with Carter, but with the Cubans who came to that meeting. They were given very important moral support.

We held a meeting at the Riviera Hotel, in a room that was the old casino. I met with former compañeros of the 26th of July who had broken with the Revolution, who were ex-prisoners. One of them came to see me and told me: “I have to leave Cuba, every time I ask for a job, they look for my record and I am a person who has just been released from prison as a counterrevolutionary, I have to leave this country, but how can I leave?”

What perspectives did a person like that have? And there were a lot of prisoners who had already served their time and were trying to live their lives. Their families had left for the U.S. They felt they had a right to be allowed to enter the country. The U.S. policy was to allow that element to exist inside Cuba. That is why it was a vindication and an achievement of the Cuban government and of the representatives of the Cuban community abroad who participated and reached that agreement.

Esther: How would you describe the atmosphere of the meetings?

Alarcón: It was a very civilized, relaxed dialogue. In that previous meeting with me, it was agreed to make a tribute to Martí, in the Plaza de la Revolución. And a young emigrant, Mariana Gaston, together with a professor who had left Cuba before the triumph of the Revolution, Jose Juan Arrom, laid a wreath there.

I remember already during the sessions a Batistiano who had been senator for Camagüey and his only objective was to visit Camagüey. He said he wanted to see the co-religionists, a word that was no longer used. There was, for example, Luis Manuel Martinez, who had been a notorious Batista supporter and had a radio program that was like a spokesman for the dictatorship. But the atmosphere was not tense. It may have helped that we had known each other before and that the Cuban mission to the UN had made the arrangements.

That 1978 meeting, from the point of view of U.S. policy, was contrary to the interests and position of the U.S. We must recognize that all those who came, whatever their political position, did not fail to break that line. And there was also the longing for the land, which is very important in people’s lives.

===================

Esther: There is a whole history of emigration from Cuba to the U.S. before 1959 and up to the present. You have insisted on not seeing this milestone of ’78 as an isolated event but as a continuity of a whole historical process that goes back to the 19th century. How do you propose to value that connection?

Alarcon: Let’s think about what happened in Havana between February and September 1869. According to official publications of the Kingdom of Spain at that time, 100,000 people left for New York through the port of Havana. Cuba then had a population of 1 million inhabitants. There have been other mass exoduses, but none compares to that one. In addition, they traveled to Mexico, Hispaniola and Venezuela. The element of emigration is absolutely vital to understand the history of Cuba. This is not the case with other countries, but it is with us.

At the same time, there is the manipulation of the subject by the U.S. government. I have here the book Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958-1960. This is volume VI, dedicated to Cuba. If you look up the final days of the Batista regime and the early days of ’59, it looks like a mystery novel. Where was the Secretary of State on Christmas Eve? In his office communicating with his ambassador in Havana. Where was he on December 31? In his office, just the same. What did you do in the first days of January? Organize an air bridge between Columbia and the U.S. through which many henchmen left.

Later, when he installed the Cuban Adjustment Act in 1964, it is unique. It was not to adjust the status of those who were there, but for those who arrived on or after January 1, 1959. And were there few who had arrived before? According to official U.S. data, no. The Immigration and Naturalization Service published annual immigration reports. In 1958, there were three categories: Mexico, Cuba and the rest, from Canada to Argentina. There were many more Cubans illegally in the U.S. than registered, and the sum of Cubans is greater than those from the Western Hemisphere, except Mexico.

According to U.S. specialists, the number of illegal and undocumented Cubans was similar to the number of legal Cubans. Therefore, it can be assumed that the number of Cubans was significant. And what did the U.S. do? It passed a law that discriminated against those who had arrived before 1959 and, on the other hand, opened the doors to those who arrived after that date, in order to turn it into an instrument of destabilization. It was a unique case and there is no other similar law for any other country on the planet.

If you go through this book you will see how since 1958 the U.S. government tried to save Batista, then tried to save the Batista regime, then see how they tried to put an end to the Cuban Revolution, everything is explained here since 1958.

The Cuban is a peculiar human being, he was born or belongs to the family of a people, of a unique nation, in the sense that they have attributed to him the right to move from Cuba to the USA, on the one hand. On the other hand, facing a government that does everything possible to prevent such a thing from happening naturally.

We must remember, for example, the case of Nicolás Gutiérrez Castaño, known as Niki. He was born in Costa Rica. Later he moved to Miami. He is the president of the Association of Cuban Farmers in exile. They are still organized, they aspire to recover all that. I have read several interviews with him that are nice, he has a sense of humor. Once he was asked: “Do you want to take away people’s houses and lands? He said: “No, what I want to remind them is that they owe me 60 years of rent”. He is the heir of a family that owned a good part of what goes between Cienfuegos and Santa Clara, from the Zapata Swamp to the Escambray, all that belonged to his great-grandfather, actually the owner was Nicolás Castaño, but he had no sons, a female married a certain Gutiérrez and that’s where he comes from.

We are talking about a situation that has accompanied us throughout history and is still with us. It would be a mistake to think that it does not exist. One of the fundamental problems that Cubans face in the relationship with the U.S. is manipulation, on the one hand the enormous difference between the fact that for the U.S., Cuba is an issue of minor importance. Now, for Cuba, the U.S. is the big issue, it is the big problem. How to deal with that? How to change that situation?

Putting an end to that hostility requires a lot of work and effort to achieve something that is essential, not so much for people my age but for people like you and your sons and daughters. Niki claims his great-grandfather’s property. Those who will be affected if that property were to pass again to its supposed former owners, do they know? How many Cubans today are aware of the terrible threat that has existed over Cuba from the U.S.?

On the other hand, you find people who have never been to Cuba, who have never lived here, but who know what belonged to their great-grandfather and aspire to get it back. That is not a joke, it is in the laws, the Helms Burton Act says so. It says that in the future of Cuba, after the Revolution falls, relations between a future government of Cuba recognized by the U.S. will continue to have as an indispensable condition the solution of the issue of the properties nationalized in Cuba in 1959. That law is in force today. How much time do we spend explaining that?

Esther: I was a child, but I lived through the visit of the Antonio Macero Brigade and the Dialogue of ’78. For a 20-year-old, that’s already history. In my opinion, that meeting was a turning point in terms of the Cuban government’s relationship with Cubans living abroad. What is your personal vision, and above all from the human point of view, about the importance for Cuba of the Cubans living abroad? Do you feel that the leadership of the Cuban Revolution really recognizes that it is unavoidable to take into account that emigration is part of Cuba? Or not? And I ask you to think about how the issue has evolved since that crucial moment in 1978 until today.

Alarcon: Of course they are part of the Cuban nation. I have gone back over history to refer to something that is obvious and has been so for a long time. Since Cuba began to crawl as a nation, a fundamental element was the Cubans who did not reside in Cuba. From Céspedes, through Martí and up to Fidel, the issue of emigration is key to the whole Cuban political process.

In addition, we must take into account that the current situation is more complicated, since Trump arrived,. In one fell swoop he put an end to things that had been achieved at the end of the Obama administration and that facilitated Cuba’s ties with its emigration. I have no doubt that none of that is going to put an end to the pressure of Cubans who want to exercise their right to have a link with their country. It is an issue that is going to remain in force.

Esther: I feel that perhaps you have something left to say, perhaps on a personal level… And I also think that to close the cycle we should remember that you also witnessed the so-called Rafters’ Crisis and had an important participation in the negotiations that followed…

Alarcón: I participated in I don’t know how many meetings with representatives of the U.S. government to deal with issues related to emigration. We reached an agreement in 1994 that gave Cuba practically nothing, but they could receive up to 20,000 Cubans in the U.S. It is impossible for any country to have that number of Cubans. It is impossible for any country to have that number. And in 1995 we reached an agreement that literally says that the U.S. commits to giving 20,000 visas every year. They enforced it pretty exactly, especially in the early days. Why did they do this? They had to recognize that there was a moral obligation, a duty of the U.S. to make sure that Cubans who wanted to emigrate could do so because the Cuban is the only human being who believes he was born with the right to live in the U.S. That is the fault of history, of all times.

I will tell you something more personal. When I was in MINREX, I had to go to Paris. And Raúl Roa Kourí was the Cuban ambassador to France. He told me: “here is a lady who says she is your cousin and wants to talk to you”. With that cousin, with whom I communicate in French because she doesn’t even speak Spanish, I had a long conversation there. She wanted to come and visit Canagüey because she remembered the stories an aunt used to tell her and that stuck with her. That’s why I tell you that this issue of emigration and the nation has to be looked at very carefully, at least for Cubans.

When I was in New York as ambassador, I met another cousin, a Salvadoran, she was a diplomat, with the last name of Quesada. Because when the war of 1868, the Quesada family went to Paris and Central America.

This idea of terroir, that one belongs to a narrow little place on Earth with little connection to the rest of the world, there are those who can understand it that way, but it is very difficult for someone with my last name not to see himself as part of the world or not to see himself reflected, in the personal and family case, in a reality that we call emigration.

Notes of A Veteran Fidelista

Notes of a Veteran Fidelista

By Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

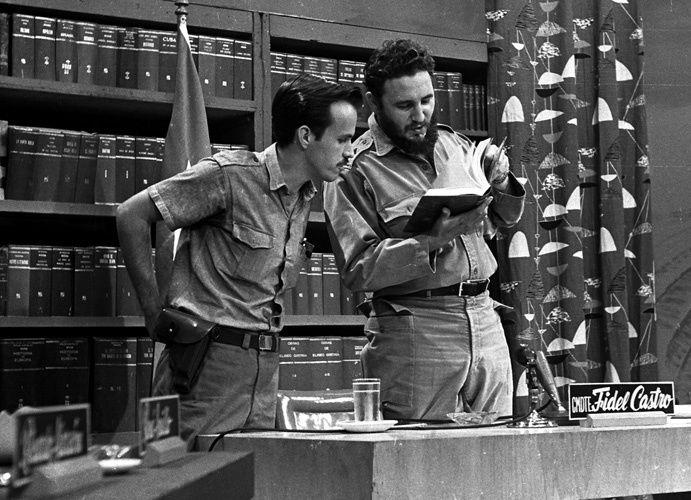

Ricardo Alarcón and Fidel Castro Ruz, Popular University Program, circa 1960- Photo: Liborio Noval.

On March 10, 1952, with a door slam, a chapter of Cuban history came to a close. Fulgencio Batista –who, two decades before, had introduced a harsh dictatorship– seized power once again with a handful of his former collaborators had liquidated the revolutionary government of just one hundred days which had emerged in 1933 after the fall of Gerardo Machado. The new coup took place without major setbacks and thus ended Cuba’s brief experience with “representative democracy”. This had lasted for only two terms of the Cuban Revolutionary Party (Autentico), which had governed for little more than seven years.

The “Autentico” Party presented itself as heir to the Revolution of 1933, in which its leaders had had played an outstanding role, but did not go beyond national-reformism, creating some necessary institutions and showing an independent foreign policy on some important issues at the UN and the OAS. Its work was, however, hampered by government corruption which invaded almost all branches of the administration. Besides, its adherence to McCarthyism led to the division among the trade union and popular movement, and the assassination of some of its main leaders.

The prevailing dishonesty caused the split in the “Autentico” Party and the emergence of the Cuban People’s Party (Orthodox) which raised the slogan “Vergüenza contra Dinero [Shame against money]” as its main banner. Among its founders was a recently graduated lawyer named Fidel Castro Ruz.

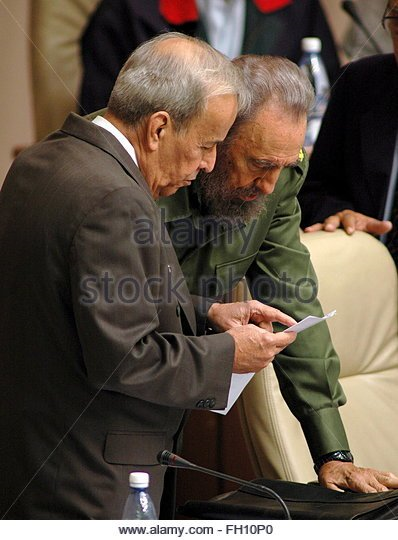

Fidel Castro, Juana Vera, Victor Rabinowitz and the author in Havana.

The general elections scheduled for June 1952, brought face-to-face, according to all polls, two candidates: the “orthodox”, headed by a respected university professor [Roberto Agramonte], and the government official, led by an “autentico” whose honesty was beyond doubt. A third candidate, Batista, supported by reactionary groups, appeared in a distant last place and no one gave him the slightest chance of winning in the polls. Everyone in Cuba knew this, including Batista who, for that reason, prevented the people from deciding.

The coup and its immediate aftermath deeply wounded Cuban society. Batista received immediate support from the big property owners as well as from the conservative political forces and corrupt trade union bureaucracy. Political parties –the ones close to the government as well their opponents– were trapped in inaction and inconsistency. Authenticism and orthodoxy were divided into contradictory trends and new parties emerged from them; some willing to collaborate or compromise with the new regime. These and all other parties engaged in endless controversies unable to articulate a path against tyranny.

Resistance found refuge in the universities. Out of these came the first demonstrations and acts of protest. Among the students there was a growing awareness of the need to act and to do so using methods different from those of the politicians who had failed miserably. There was talk of armed struggle, but nobody knew how to wage it or had the resources to undertake it. There were some isolated attempts while rumors spread about plans led or linked to the president overthrown on March 10.

For those of us who were still in secondary education, the assault on the military barracks in Santiago de Cuba (Moncada) and Bayamo (Carlos Manuel de Cespedes), on July 26, 1953, was a complete surprise. We knew nothing of an event that would change our lives forever.

The news highlighted the name of someone previously unknown to us: Fidel Castro.

The political crisis deepened. The tyranny became even more aggressive. The Communist Party (Partido Socialista Popular [Socialist People’s Party]) was banned and its publications closed, while increased repression against the student movement became the norm. Batista’s accusations against the Communists sought the sympathy of Washington, but had nothing to do with reality. The PSP was not only alien to those events, but rather condemned the action of the young revolutionaries as did the other opponents to Batista, almost without exception.

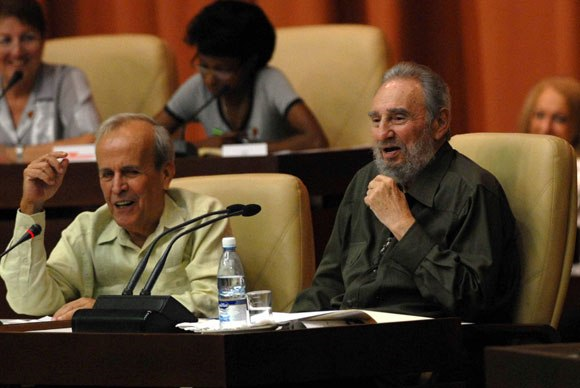

With Puerto Rican Independentists, Lolita Lebrón, Rafael Cancel Miranda, Irving Flores and Oscar Collazo, Havana 1979.

Once again it fell to the students to replace the parties that had proved incapable of fulfilling their role. The Federation of University Students (FEU) sympathized with the attackers of the Moncada garrison and called for a campaign for their release. This soon acquired a national dimension and forced the dictatorship to grant them amnesty in 1955.

That same year, Fidel founded the July 26th Movement. Along with the survivors of the initial action, it counted especially on young people who, in neighborhoods and study centers, identified themselves with that heroic deed against tirades and criticism from Tiryns and Trojans.

Their ranks were filled with youths, no few of them teenagers, who rebelled amid frustration, inertia and division, inspired by a feat that had shaken the tyranny and its opponents as well. Antonio López (Ñico), who had led the attack on the barracks in Bayamo, was responsible for organizing the youth brigades of the M-26-7 until he went to Mexico to return with Fidel and die fighting in the Sierra Maestra. He was replaced in Havana by Gerardo Abreu (Fontán), a black man of very humble origin, who had not completed primary school. He managed, on his own, to acquire a broad cultural background and a poetic sensibility that caused astonishment among us college students who had the privilege of fighting under his leadership. Ñico and Fontán –both from the Orthodox Youth– knew Marxism, shared socialist ideals, and were profoundly anti-imperialist. They were determined to create an organization that would massively bring in the new generation. They succeeded. Their followers were identified with a single word: “fidelistas”.

The presence of the Brigades was felt quickly by sending their message directly to the people. While the press and politicians criticized Fidel and the Moncada action, everywhere, in every corner of the capital –on walls and facades– using very modest resources, Brigade members painted a brief slogan which everyone understood: M-26-7, or a name that others wanted to silence: Fidel.

In view of the hostile environment which made it impossible to wage open political struggle, Fidel went to Mexico in order to organize the return to carry out the battle that would end the tyranny. He proclaimed it openly, undertaking a historic commitment: “In ’56, we will be free or we will be martyrs” thus challenging the followers of inaction and despair once again. And also their jokes: a government newspaper carried on its front page every day the number of days which had elapsed that year without the defiant promise being kept.

Well into November, the propaganda against the Moncadistas intensified. Demonstrations, organized by the FEU and the newly created Revolutionary Directorate, climaxed and led to the closure of the university. The last day of the month, to support the landing [of the Granma expedition], the M-26-7 carried out an uprising in Santiago de Cuba. Two days later Fidel and his companions arrived at the eastern shores aboard the yacht Granma, in what Che described as a “shipwreck”.

Scattered and persecuted by the Army, a small group finally managed to reunite in the Sierra Maestra. Many members of the expedition died fighting, or were assassinated.

Among these, as the US news agencies reported, was its main leader. Fidel’s death was reported on the front page of every newspaper. Anguish and uncertainty remained until after a passage of time that seemed endless. Gradually and by clandestine channels, the truth came to be known.

The last two years of the dictatorship were rife with crimes and abuses in the urban areas while the initial guerrilla force grew to become the Rebel Army.

“Fidelismo” reached massiveness. On the night of November 8, 1957, one hundred simultaneous explosions rocked Havana, each in a different neighborhood and distant from one another. They were practically heavy firecrackers –rather homemade devices– that only made noise. No one was injured and no one was arrested by the police who went around frantically from one place to the other. It was sound evidence that the “26th” was everywhere and showed the youth brigades’ efficient organization.

The murder of Fontan, on February 7, 1958, sparked a students’ general strike which lasted until May. It paralyzed all education centers, including private universities and academies, and led to the consecutive resignations of two of Batista’s Education Ministers of Batista.

Never before had such a movement occurred in Cuba to such extent and for so long. For three months, all attempts, violent or “peaceful” to end it failed. The student walkout continued, even several weeks after the movement suffered in its most painful and bloody defeat in Havana.

The failure of the attempted general strike by the workers, on April 9, was a very severe blow. It decimated urban militancy, almost completely destroyed the underground structures, and allowed the dictatorship to mobilize thousands of troops to launch what it thought would be the final battle in the Sierra. Once again everything depended on Fidel and his leadership.

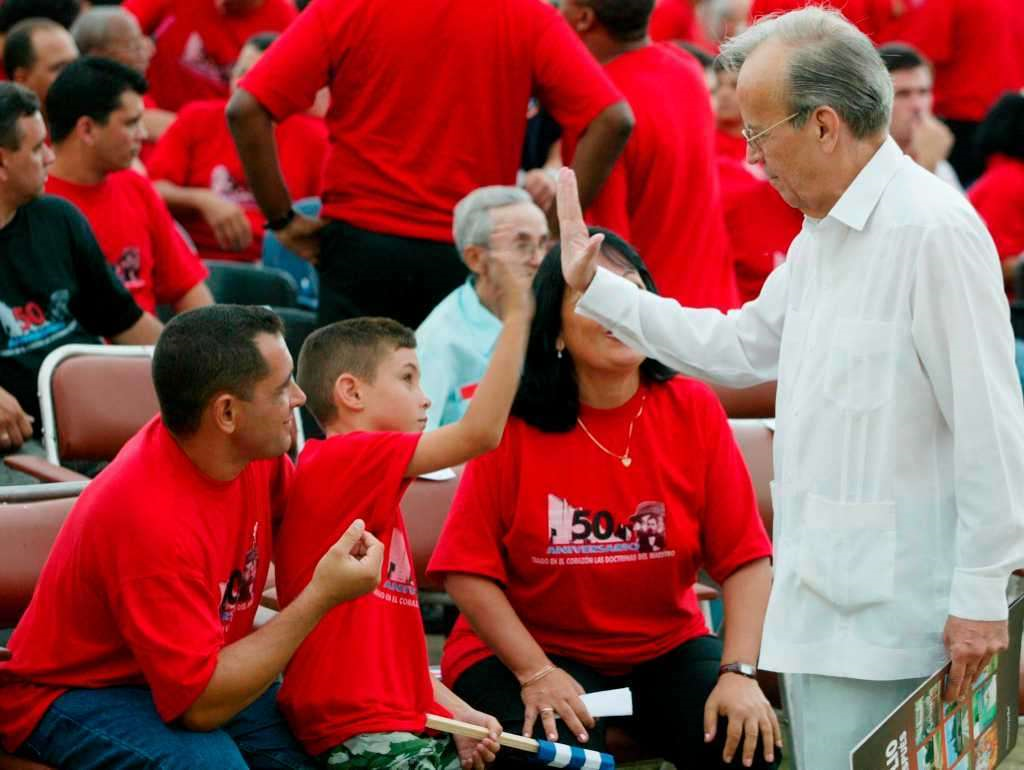

PHOTO Elian and Juan Miguel Gonzalez, at the Celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the Moncada assault.

Batista’s offensive proved a complete failure. The Rebel Army –well-established in the East– sent two columns led by Che and Camilo Cienfuegos, which crossed half the island and won many battles in its central region. The rebels were close to liberating the cities of Santiago de Cuba and Santa Clara. The last day of December, the dictator arranged his escape and –in close coordination with the US Ambassador– left behind a military junta in Havana that would have been the continuity of his regime. To thwart the maneuver, Fidel called for a general strike.

In the early hours of the first day of the New Year, the people took over the streets in the capital. The youth brigades –almost totally unarmed– occupied all police stations without meeting resistance from the demoralized and nervous troops of the regime. However, in other parts of the city, armed paramilitary groups of Batista henchmen had to be confronted. The strike continued until the total collapse of the tyranny. On January 8, Fidel rode triumphantly into a city that was already and finally “Fidelista”.

The victorious Revolution would have to face more powerful obstacles and even greater risks for over half a century: Political, diplomatic and propaganda aggression, armed attacks, subversion and sabotage, and the economic blockade that is still ongoing and is the longest genocide in history. Another blow was the collapse of the U.S.S.R. and the disappearance of allies and trading partners plus the complete isolation of the island. It has been a long and stormy path that the people have weathered under Fidel’s guidance.

Ninety years of age has now come to the man who had to face more than six hundred assassination plots against his life and whose death has been announced countless times by imperialist propaganda. Maybe someday his enemies will have to admit that they were never able to kill him. This is because Fidel and his people are one and the same. And that people, largely thanks to him, is invincible.

Ricardo Alarcón on Micheal Ratner

- English

- Español

Micheal Ratner

By Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada

A CubaNews/Google translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

He came to Cuba often. The last time was in February 2015, on the occasion of the International Book Fair in which the Spanish edition of “Who Killed Che? How the CIA Got Away with Murder” was presented. It was the result of painstaking research and more than ten years demanding access from relevant authorities to official documents jealously hidden.

The work of Michael Ratner and Michael Steven Smith proved beyond doubt that the murder of Ernesto Guevara was a war crime committed by the US government and its Central Intelligence Agency, a crime that does not have a statute of limitations, Although the authors are on the loose in Miami and flaunt their cowardly misdeed.

We met again in July on the occasion of the reopening of the Cuban Embassy in Washington. We were far from imagining that we would not meet again. Michael Ratner looked healthy and showed the optimism and joy that always accompanied him. Then we celebrated the return of our Five anti-terrorists Heroes to the country and also the fact that President Obama had no choice but to admit the failure of Washington’s aggressive policy against Cuba.

Michael was always in solidarity with the Cuban people since as a very young person he joined the contingents of the Venceremos Brigade. That solidarity remained unwavering at all times. His participation in the legal battle for the freedom of our companions, including the “amicus” he presented to the Supreme Court on behalf of ten Nobel Prize winners, was decisive.

A tireless fighter, for him no cause was alien. He stood always on the side of the victims and faced with courage, even at the risk of his life, the oppressors who dominated that judicial system. He also did it with rigor, integrity and love. More than a brilliant legal professional, he was a passionate fighter for justice.

He was present in 1968 at the Columbia University strike before completing his studies, and fought racial discrimination together with the NAACP. The recent graduate represented the victims of brutal repression at the Attica prison. Thus he began a remarkable career –impossible to describe in an article– which knew no borders: Nicaragua, Haiti, Guatemala, Palestine, and so on.

When nobody did, he undertook the defense of the hostages in the illegal naval base in Guantanamo. He convened more than 500 lawyers to do so –also for free– and achieved a legal victory with an unprecedented decision by the Supreme Court recognizing the rights of the prisoners.

Many other cases absorbed his time and energy, working in a team, without necessarily appearing in the foreground. He did not hesitate, however, to legally prosecute powerful characters like Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush whose “impeachment” he tried very hard to obtain.

He also accused Nelson Rockefeller, when he was governor, and more recently Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. He published books and essays in favor of legality and human rights. He was considered one of the best American lawyers and chaired the National Lawyers Guild and the Center for Constitutional Rights and founded Palestine Rights. He combined his work as a litigator with university teaching at Columbia and Yale and helped train future jurists able to follow his example.

He was the main defender of Julian Assange and Wikileaks in the United States. An insuperable paradigm of a generation that wanted to conquer the sky, he was an inseparable part of all their battles and will remain so always until victory.

—–

Reposted: https://ajiacomix.wordpress.com/2016/05/19/micheal-ratner/

juhn

Micheal Ratner

Por: Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada

Muchas veces vino a Cuba. La última fue en febrero del 2015, con motivo de la Feria Internacional de Libro en la que fue presentada la edición en español de “¿Quién mató al Che? Como la CIA logró salir impune del asesinato”, fruto de minuciosa investigación y más de diez años reclamando a las autoridades el acceso a documentos oficiales celosamente ocultos. La obra de Michael Ratner y Michael Steven Smith demostró de manera inapelable que el asesinato de Ernesto Guevara fue un crimen de guerra cometido por el gobierno de Estados Unidos y su Agencia Central de Inteligencia, un crimen que no prescribe aunque sus autores andan sueltos en Miami y hacen ostentación de la cobarde fechoría.

Nos encontramos de nuevo en julio en ocasión de la reapertura de la Embajada cubana en Washington. Lejos estábamos de imaginar que no nos veríamos más. Michael Ratner parecía saludable y mostraba el optimismo y la alegría que siempre le acompañaron. Celebramos entonces que ya nuestros Cinco Héroes antiterroristas habían regresado a la Patria y que el Presidente Obama no tuvo otro remedio que admitir el fracaso de la política agresiva contra Cuba.

Porque Michael fue siempre solidario con el pueblo cubano desde que muy joven integró contingentes de la Brigada Venceremos y esa solidaridad la mantuvo sin flaquezas en todo momento. Fue decisiva su participación en la batalla legal por la libertad de nuestros compañeros incluyendo el “amicus” que presentó a la Corte Suprema a nombre de diez ganadores del Premio Nobel.

Incansable luchador para él ninguna causa fue ajena. Se puso siempre del lado de las víctimas y encaró con valor, aun a riesgo de su vida, a los opresores que dominan aquel sistema judicial. Y lo hizo, además, con rigor, entereza y amor. Más que un brillante profesional del derecho fue un apasionado combatiente por la justicia.

Estuvo presente en 1968 en la huelga de la Universidad de Columbia y antes de concluir sus estudios combatió la discriminación racial junto al NAACP. Recién graduado representó a las víctimas de la brutal represión en la prisión de Attica. Inició así una trayectoria admirable imposible de describir en un artículo y que no conoció fronteras: Nicaragua, Haití, Guatemala, Palestina, y un largo etcétera.

Cuando nadie lo hacía asumió la defensa de los secuestrados en la ilegal base naval de Guantánamo, pudo incorporar a más de 500 abogados que lo hicieran también gratuitamente y alcanzó una victoria jurídica sin precedentes con la decisión de la Corte Suprema reconociendo los derechos de los prisioneros. A muchos otros casos también dedicó su tiempo y energías, trabajando en equipo, sin aparecer necesariamente en primer plano. No vaciló sin embargo en encausar legalmente a personajes poderosos como Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton y George W. Bush cuyo “impeachment” trató afanosamente de conseguir, y acusó también a Nelson Rockefeller cuando era Gobernador y más recientemente al Secretario de Defensa Donald Runsfeld. Publicó libros y ensayos a favor de la legalidad y los derechos humanos. Considerado uno de los mejores abogados norteamericanos presidió el National Lawyers Guild y el Center for Constitutional Rights y fundó el Palestine Rights. Conjugó su labor como litigante con la docencia universitaria en Columbia y Yale y ayudó a la formación de futuros juristas capaces de seguir su ejemplo.

Era el principal defensor en Estados Unidos de Julian Assange y Wikileaks. Paradigma insuperable de una generación que quiso conquistar el cielo fue parte inseparable en todas sus batallas y lo seguirá siendo hasta la victoria siempre.

USA and Cuba: one year later

USA and Cuba: one year later

by Ricardo Alarcón

Published on December 19, 2015 in Opinión, Política, Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada

December 17 marks the first anniversary of the announcement that Cuba and the United States would reestablish diplomatic relations. Presidents Raul Castro and Barak Obama did it at the same time from Havana and Washington, respectively. They both admitted that it was barely the first step of a process toward the elimination of a hostile policy maintained for over half a century but failed in the end, as the White House resident himself acknowledged.

Since then, Embassies were reopened, some senior officials have visited Havana, several minor or relatively important problems have been solved, and representatives of both governments have held meetings to discuss a thick agenda of essential topics, including the economic blockade —still in place— the permanent occupation of Cuban territory in Guantanamo, and the subversive projects that remain in operation to undermine the Revolution. As long as Washington makes no radical changes in its policy —lifting the blockade completely, returning Guantanamo to Cuba and ending its interference in our affairs— calling such diplomatic relations “normal” would be a bad joke.

There is a question, however, that seems to be a favorite on the American side and to which several of that country’s most read publications have devoted their attention: the claims filed there for alleged losses suffered by corporations and individuals as a result of Cuba’s nationalization laws of 1960.

This issue would have to be discussed together with Cuba’s own claims for the damages caused by fifty years of economic war and aggression which are incomparably greater and have had a serious impact on the island’s population. An official document that used to be secret, but no longer is, recognizes that the purpose of the policy was to make the Cuban people “suffer” by “hunger and despair”. Approved in the spring of 1960, the text was written before the Cuban nationalizations, and its words are literally consistent with what the Geneva Convention calls the “crime of genocide”.

The revolutionary laws always included the right to fair compensation by the former owners. All those foreign companies that respected Cuba’s sovereignty and accepted our legislation benefited, without exception, from such laws, and have kept normal links with us through business and new investments. It was also the case, by the way, with individuals living in Cuba who adopted the same attitude.

The North American companies were the only ones excluded, owing to their government’s rejection of the Cuban legislation and their economic attacks.

Still, there is an aspect of this issue that the U.S. media are carefully ignoring. It’s been a long time now since those who were expropriated in Cuba received special and privileged treatment that allowed them to get compensation for what they supposedly lost to the revolutionary measures.

Starting in 1964, and ever since, regulations were amended and unique laws were adopted exclusively for that group of people that made it possible for them to obtain compensation for their losses by means of substantial tax deductions. No other American taxpayers were granted similar benefits.

As far as taxes were concerned, it was an exceptional treatment only comparable to what migrants receive under the Cuban Adjustment Act, which also came in handy to individuals who in 1960 had not yet become American citizens but also enjoyed those advantages and helped create the myth of a successful Cuban-American business sector.

It was the Cuban people who never got any compensation whatsoever. The blockade has been not only the main obstacle to the island’s development, but also the main cause of that people’s suffering. It’s a genocidal policy, the longest genocide in history. The United States has an obligation to lift it now, immediately and unconditionally, and they must try to compensate their victims if they wish to have relations with their neighbors worthy of being considered “normal”.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

You must be logged in to post a comment.