Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada:

Cubans living abroad are part of the Cuban nation

By Esther Barroso Sosa, June 20, 2021/

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

At the age of 84, after having been Cuba’s representative to the UN, Minister of Foreign Affairs and President of Parliament for two decades, among other political functions, he dedicates his days to “things like this”, that is, to giving interviews, such as the one we have asked him to give for the TV series Relatos in(contables), an audiovisual proposal still in the making. Even knowing that the recording has no broadcast date, he has not hesitated to accept.

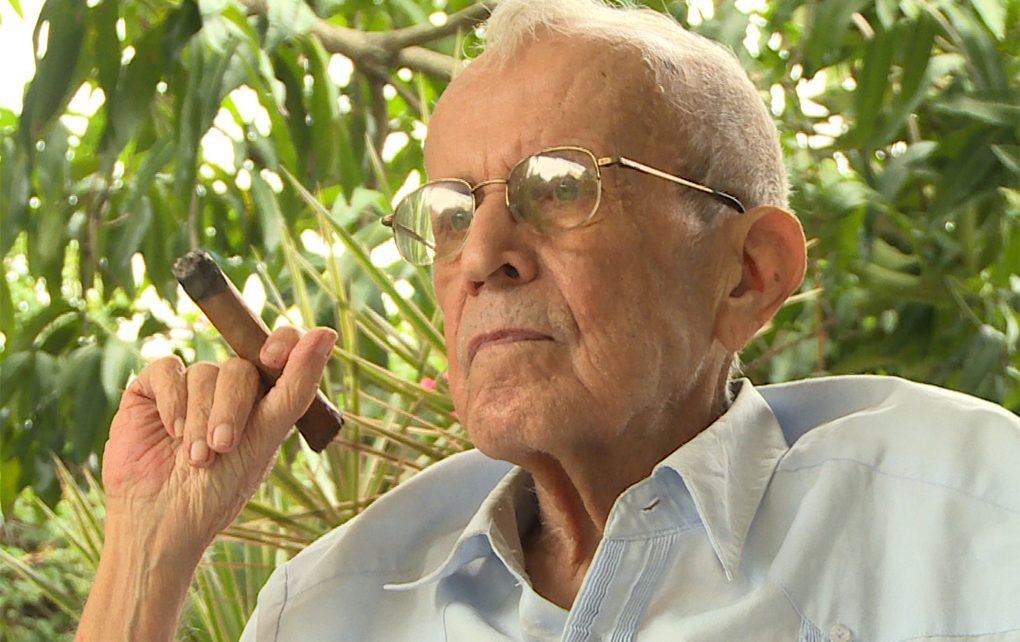

He lights up a cigar only after the long conversation on a subject he is passionate about is over. And that’s when, at my insistence, he replies, “Yes, I’m writing something about my life, but if I’m going to tell everything I know…” The unfinished answer is probably hotter than the cigar that is already being consumed as we say goodbye. Me, with the promise to publish in full and in print what I have narrated. He, recreating himself with the shapes drawn by the smoke of his cigar.

Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada is a descendant of the family of the second wife of the Father of the Cuban Homeland: Ana de Quesada y Loynaz (1843-1910), who died in Paris, as one more emigrant and after a brief stay in the U.S., where Carlos Manuel de Cespedes sent her, trying to protect her from the rigors of the manigua [jungle] and the threats that were already made against the deposed president of the republic-in-arms.

The nation-emigration issue has not been alien to Alarcón. On the contrary. And not only because his predecessors are scattered around the world, but also because he was one of the promoters of the first dialogue between the Cuban revolutionary government and a representative group of the Cuban community in the United States.

From 1966 to 1978, Alarcón remained in New York as Cuba’s permanent ambassador-representative to the United Nations. From there he witnessed the birth and evolution of initiatives that sought a rapprochement, often critical, with Cuba and its Revolution. Organizations such as Juventud Cubana Socialista, magazines such as Areíto and Joven Cuba, the Institute of Cuban Studies or the Antonio Maceo Brigade -with its impressive first trip to the island at the end of 1977- were some of the antecedents of the Dialogue that would finally be held on November 20 and 21, 1978, after a press conference in September in which Fidel invited representatives of the community to come to the island for that purpose, with the sole condition that no leaders of the counterrevolution or active terrorists would attend.

Seventy-five members of the Cuban community in the United States participated and 140 in a second meeting held on December 8. Alarcón was one of the nine Cuban leaders who, headed by Fidel, made up the representation of the government of the island.

Esther: Shortly before the 1978 Dialogue, you had just returned from the Cuban Mission to the UN. There you had experienced the rapprochement of Cuban emigrants who were interested in being reunited with their country. They had a vision of the Cuban Revolution different from that of the most radical elements of the right-wing of the Cuban community in that country. How did that rapprochement take place, what do you remember of that stage in New York?

Alarcón: The 1978 dialogues with the Community were part of an interesting process of rapprochement. The Antonio Maceo Brigade and other projects arose and everything changed at that time and it will change more and more. It was at the Cuban Mission to the UN, in New York, where it all began. I was the only one at that table who knew almost all the Cuban emigrants who participated in the meeting.

Since I arrived in New York I have had many relationships with Cubans who were living abroad. That is not after the Revolution. You just get there and you discover that lots of Cubans who came to the U.S., many of them illegally, had originally received a B-29 visa, a type of visa that the U.S. gave for visitors, and the classification was with the letter B and for 29 days.

There were many friends that I knew who had arrived for 29 days before 1959 and were still there. It was amazing. They had a strong relationship with the only diplomatic representation Cuba had, because this was before the Interests Section existed. It was logical for them to look for that space. How could a Cuban in New York connect with his family if there were no flights and hardly any communication?

At the same time, there was the Casa de las Americas, which was the continuation of Casa Cuba, dating back to the Revolution of 1930 or earlier, Cubans living in the U.S. who maintained ties with their country of origin and with the Revolution. Little by little, we became closer to them. I used to go to Casa de las Americas a lot, it was the only social place where we could meet Cubans, play dominoes, drink beer. And it was maintained with the contribution of those Cubans.

When you look at their history, there were a lot of them who were B-29s, others were their children. It was a contact center that allowed us to meet a lot of people who, regardless of their ideology, wanted to have a link with their country of origin.

That explains why I was given the task of organizing, inviting and bringing representatives of that community to Cuba, because they were not representatives of something, nobody had elected them, but they were representative of that diversity. We are talking about 1978, almost 20 years after the triumph of the Revolution. There were people who had been changing their point of view. Practically all those who came, I knew them. There were also militant Batista supporters, some of them famous.

Esther: But there was a predominance of young people and especially Cubans who had left very young in the first years after the triumph of the Revolution?

Alarcón: Yes, and for them, it was a challenge. What they were doing was contrary to U.S. government policy. They were emigrants, people residing in a foreign country, so they were in a weak situation. It is logical that among the younger ones there were people willing to take those risks, besides the fact that they had very little connection with the counterrevolution, unlike the older ones.

Esther: There was also a context that favored that: Carter’s position towards Cuba on the one hand and on the other the Cuban government’s willingness to receive them and talk. To what extent did that dialogue come about because of pressure from those Cubans in the U.S. and to what extent did the fact that Fidel and the revolutionary leadership realized that it was necessary to establish that link have an influence? Does what they achieved deserve recognition? What was the driving force behind that dialogue? They had three fundamental objectives that became the three great themes of the Dialogue: that the emigrants be allowed to visit Cuba, family reunification and the release of political prisoners.

Alarcón: Fidel was interested in it being a dialogue with Cubans and not with the U.S. government. Those Cubans achieved, among other things, the visits to Cuba and those permits also depended on the U.S. But the release of the counterrevolutionary prisoners was a unilateral decision of the Cuban government. And it was made, not with Carter, but with the Cubans who came to that meeting. They were given very important moral support.

We held a meeting at the Riviera Hotel, in a room that was the old casino. I met with former compañeros of the 26th of July who had broken with the Revolution, who were ex-prisoners. One of them came to see me and told me: “I have to leave Cuba, every time I ask for a job, they look for my record and I am a person who has just been released from prison as a counterrevolutionary, I have to leave this country, but how can I leave?”

What perspectives did a person like that have? And there were a lot of prisoners who had already served their time and were trying to live their lives. Their families had left for the U.S. They felt they had a right to be allowed to enter the country. The U.S. policy was to allow that element to exist inside Cuba. That is why it was a vindication and an achievement of the Cuban government and of the representatives of the Cuban community abroad who participated and reached that agreement.

Esther: How would you describe the atmosphere of the meetings?

Alarcón: It was a very civilized, relaxed dialogue. In that previous meeting with me, it was agreed to make a tribute to Martí, in the Plaza de la Revolución. And a young emigrant, Mariana Gaston, together with a professor who had left Cuba before the triumph of the Revolution, Jose Juan Arrom, laid a wreath there.

I remember already during the sessions a Batistiano who had been senator for Camagüey and his only objective was to visit Camagüey. He said he wanted to see the co-religionists, a word that was no longer used. There was, for example, Luis Manuel Martinez, who had been a notorious Batista supporter and had a radio program that was like a spokesman for the dictatorship. But the atmosphere was not tense. It may have helped that we had known each other before and that the Cuban mission to the UN had made the arrangements.

That 1978 meeting, from the point of view of U.S. policy, was contrary to the interests and position of the U.S. We must recognize that all those who came, whatever their political position, did not fail to break that line. And there was also the longing for the land, which is very important in people’s lives.

===================

Esther: There is a whole history of emigration from Cuba to the U.S. before 1959 and up to the present. You have insisted on not seeing this milestone of ’78 as an isolated event but as a continuity of a whole historical process that goes back to the 19th century. How do you propose to value that connection?

Alarcon: Let’s think about what happened in Havana between February and September 1869. According to official publications of the Kingdom of Spain at that time, 100,000 people left for New York through the port of Havana. Cuba then had a population of 1 million inhabitants. There have been other mass exoduses, but none compares to that one. In addition, they traveled to Mexico, Hispaniola and Venezuela. The element of emigration is absolutely vital to understand the history of Cuba. This is not the case with other countries, but it is with us.

At the same time, there is the manipulation of the subject by the U.S. government. I have here the book Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958-1960. This is volume VI, dedicated to Cuba. If you look up the final days of the Batista regime and the early days of ’59, it looks like a mystery novel. Where was the Secretary of State on Christmas Eve? In his office communicating with his ambassador in Havana. Where was he on December 31? In his office, just the same. What did you do in the first days of January? Organize an air bridge between Columbia and the U.S. through which many henchmen left.

Later, when he installed the Cuban Adjustment Act in 1964, it is unique. It was not to adjust the status of those who were there, but for those who arrived on or after January 1, 1959. And were there few who had arrived before? According to official U.S. data, no. The Immigration and Naturalization Service published annual immigration reports. In 1958, there were three categories: Mexico, Cuba and the rest, from Canada to Argentina. There were many more Cubans illegally in the U.S. than registered, and the sum of Cubans is greater than those from the Western Hemisphere, except Mexico.

According to U.S. specialists, the number of illegal and undocumented Cubans was similar to the number of legal Cubans. Therefore, it can be assumed that the number of Cubans was significant. And what did the U.S. do? It passed a law that discriminated against those who had arrived before 1959 and, on the other hand, opened the doors to those who arrived after that date, in order to turn it into an instrument of destabilization. It was a unique case and there is no other similar law for any other country on the planet.

If you go through this book you will see how since 1958 the U.S. government tried to save Batista, then tried to save the Batista regime, then see how they tried to put an end to the Cuban Revolution, everything is explained here since 1958.

The Cuban is a peculiar human being, he was born or belongs to the family of a people, of a unique nation, in the sense that they have attributed to him the right to move from Cuba to the USA, on the one hand. On the other hand, facing a government that does everything possible to prevent such a thing from happening naturally.

We must remember, for example, the case of Nicolás Gutiérrez Castaño, known as Niki. He was born in Costa Rica. Later he moved to Miami. He is the president of the Association of Cuban Farmers in exile. They are still organized, they aspire to recover all that. I have read several interviews with him that are nice, he has a sense of humor. Once he was asked: “Do you want to take away people’s houses and lands? He said: “No, what I want to remind them is that they owe me 60 years of rent”. He is the heir of a family that owned a good part of what goes between Cienfuegos and Santa Clara, from the Zapata Swamp to the Escambray, all that belonged to his great-grandfather, actually the owner was Nicolás Castaño, but he had no sons, a female married a certain Gutiérrez and that’s where he comes from.

We are talking about a situation that has accompanied us throughout history and is still with us. It would be a mistake to think that it does not exist. One of the fundamental problems that Cubans face in the relationship with the U.S. is manipulation, on the one hand the enormous difference between the fact that for the U.S., Cuba is an issue of minor importance. Now, for Cuba, the U.S. is the big issue, it is the big problem. How to deal with that? How to change that situation?

Putting an end to that hostility requires a lot of work and effort to achieve something that is essential, not so much for people my age but for people like you and your sons and daughters. Niki claims his great-grandfather’s property. Those who will be affected if that property were to pass again to its supposed former owners, do they know? How many Cubans today are aware of the terrible threat that has existed over Cuba from the U.S.?

On the other hand, you find people who have never been to Cuba, who have never lived here, but who know what belonged to their great-grandfather and aspire to get it back. That is not a joke, it is in the laws, the Helms Burton Act says so. It says that in the future of Cuba, after the Revolution falls, relations between a future government of Cuba recognized by the U.S. will continue to have as an indispensable condition the solution of the issue of the properties nationalized in Cuba in 1959. That law is in force today. How much time do we spend explaining that?

Esther: I was a child, but I lived through the visit of the Antonio Macero Brigade and the Dialogue of ’78. For a 20-year-old, that’s already history. In my opinion, that meeting was a turning point in terms of the Cuban government’s relationship with Cubans living abroad. What is your personal vision, and above all from the human point of view, about the importance for Cuba of the Cubans living abroad? Do you feel that the leadership of the Cuban Revolution really recognizes that it is unavoidable to take into account that emigration is part of Cuba? Or not? And I ask you to think about how the issue has evolved since that crucial moment in 1978 until today.

Alarcon: Of course they are part of the Cuban nation. I have gone back over history to refer to something that is obvious and has been so for a long time. Since Cuba began to crawl as a nation, a fundamental element was the Cubans who did not reside in Cuba. From Céspedes, through Martí and up to Fidel, the issue of emigration is key to the whole Cuban political process.

In addition, we must take into account that the current situation is more complicated, since Trump arrived,. In one fell swoop he put an end to things that had been achieved at the end of the Obama administration and that facilitated Cuba’s ties with its emigration. I have no doubt that none of that is going to put an end to the pressure of Cubans who want to exercise their right to have a link with their country. It is an issue that is going to remain in force.

Esther: I feel that perhaps you have something left to say, perhaps on a personal level… And I also think that to close the cycle we should remember that you also witnessed the so-called Rafters’ Crisis and had an important participation in the negotiations that followed…

Alarcón: I participated in I don’t know how many meetings with representatives of the U.S. government to deal with issues related to emigration. We reached an agreement in 1994 that gave Cuba practically nothing, but they could receive up to 20,000 Cubans in the U.S. It is impossible for any country to have that number of Cubans. It is impossible for any country to have that number. And in 1995 we reached an agreement that literally says that the U.S. commits to giving 20,000 visas every year. They enforced it pretty exactly, especially in the early days. Why did they do this? They had to recognize that there was a moral obligation, a duty of the U.S. to make sure that Cubans who wanted to emigrate could do so because the Cuban is the only human being who believes he was born with the right to live in the U.S. That is the fault of history, of all times.

I will tell you something more personal. When I was in MINREX, I had to go to Paris. And Raúl Roa Kourí was the Cuban ambassador to France. He told me: “here is a lady who says she is your cousin and wants to talk to you”. With that cousin, with whom I communicate in French because she doesn’t even speak Spanish, I had a long conversation there. She wanted to come and visit Canagüey because she remembered the stories an aunt used to tell her and that stuck with her. That’s why I tell you that this issue of emigration and the nation has to be looked at very carefully, at least for Cubans.

When I was in New York as ambassador, I met another cousin, a Salvadoran, she was a diplomat, with the last name of Quesada. Because when the war of 1868, the Quesada family went to Paris and Central America.

This idea of terroir, that one belongs to a narrow little place on Earth with little connection to the rest of the world, there are those who can understand it that way, but it is very difficult for someone with my last name not to see himself as part of the world or not to see himself reflected, in the personal and family case, in a reality that we call emigration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.