Translations 677

Mujica backs Cuban doctors for Nobel

Pepe Mujica: “It is an honor to support the candidacy for the Nobel Peace Prize for Cuban doctors”.

By Maribel Acosta Damas. Cuban journalist, specialized in Television. She is a professor at the Faculty of Journalism of the University of Havana and holds a PhD in Communication Sciences.

By Maribel Acosta Damas. Cuban journalist, specialized in Television. She is a professor at the Faculty of Journalism of the University of Havana and holds a PhD in Communication Sciences.

March 12, 2021

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Pepe Mujica, Minister of Livestock and Agriculture in the first government of Tabaré Vázquez in 2005 and then President of Uruguay between 2010 and 2015. Photo: Resumen Latinoamericano.

Photo taken from Cubaenresumen.org

In my living room I have a picture of Che, and I have his letters in my memoirs, in a notebook. It turned out that Evo Morales wanted to make a faithful reproduction of Che’s wallet in the Bolivian guerrilla, the last one he had. Evo Morales had it made as a gift to his friends, and I have it. Inside there is also the facsimile copy of the campaign diary and a notebook… I keep it hanging… and I always show it to them when they come to visit. Che is still there. For us, it is an indelible attitude, no matter how much time goes by…

José “Pepe” Mujica and Lucía Topolansky at the Uruguayan ambassador’s residence in Havana, January 25, 2015. Photo: William Silveira Mora

We receive all this when we are born. So we have to try to leave something behind for those who will come after us. The world will not improve if there are no people who are concerned about its improvement. The world improves because of the work of people who make an effort.

Pepe Mujica gives an interview to Randy Alonso Falcón for the Round Table, Havana, January 25, 2016. Photo: William Silveira Mora

Now there is the internet, there is the university, so it is as if the old people are superfluous, they are left over… It is a world that only wants young people, absolutely young, and then the old men and women disguise themselves to look younger. They all want to be young and they revoke themselves: they dye their hair, they remove wrinkles, they bother with fatness… in short…

Old people are on the way to being discarded. However, sometimes old people see farther because they have lived longer and if they are not yet crippled they have the function of trying to tell things to younger people that probably they are not going to understand them at that moment, but one day they will realize that they did not see part of reality… In Asian villages there is a great reverence for old people, but in Western villages there is no reverence. That is why it is good to retire…

The former Uruguayan president is known for his modest lifestyle and direct speech. Photo: EFE

A Brief Analysis of the Current Moment

- English

- Español

A Brief Analysis of the Current Moment

A Brief Analysis of the Current Moment

by Domingo Amuchastegui

February 18, 2021

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

For some time now I have insisted that we are in the presence of the gestation of what I have called “Navalny’s route a la Cubana.” Understand well “a la cubana.” What do I mean by this? We are in the presence -without the mass component so far seen in Russia or a more effective figure than Navalny- of the maturation of concerted initiatives on both shores -and with financing and sponsorship from the side here- in order to achieve the crystallization of a current or movement capable of negatively impacting the image of the Cuban Revolution, or what is left of it at this point, with its [consequent] costs both internally and externally.

To the well-known components of extreme aggravation of the crisis of the Cuban model (proven inoperative in the economic field, the sixty-year old embargo was turned into an economic war by Trump plus the multiple effects and costs of the pandemic), we must now add other no less important ones.

On an international scale, Navalny’s route is defined as the most influential -and most encouraged- option to erode the Putin option from the US and the EU. In the Cuban case, it is primarily aimed at weakening the international credibility of the Cuban government and at fostering internally superior schemes of agitation and confrontation that will increase to levels never seen before the levels of unrest and discontent in broad sectors of society with a tendency to the hypothesis of socio-political explosions of the kind called “Maleconazo”.

The following factors favor such a scenario:

a. The unprecedented levels of the current crisis;

b. There is no way out or improvement in the short or medium-term;

c. The gravitation of the “Miami” factor has grown as never before;

d. And, an extremely novel and influential factor: the accelerated computerization in recent times with its links through social networks now create levels of information and communication that escape any attempt to control or annul them.

We are not now facing the projects of the Cuban-American Foundation, the Ladies in White, Payá, etc., etc., which were exhausted and defeated in the long road from the ’90s to date. The so-called San Isidro Movement may resemble some of those old attempts, but it is now inscribed in a different perspective. Even more so are the incidents in front of the Ministry of Culture in terms of defiance and larger participation.

Episodes like this were unimaginable in the 90s. Now they are there and, eventually, [will be] called-upon to continue and multiply. A singular fact, by way of a novel milestone, is the Patria y Vida episode, which cannot be underestimated in the least, both for its content and its effects.

It would be a serious mistake to approach these novel contexts with the usual media disqualifications, police operations or violent actions (not to mention the rapid response brigades). The moment is essentially different and demands from the Cuban authorities entirely different economic-social, political, and media responses to neutralize these tendencies and re-establish, as far as possible, greater legitimacy.

And from all of the above -in order to interrupt the “Cuban Navalny route”- the so-called “historical exiles” based in Miami, and those in Washington who seek to prevent or reduce as much as possible the resumption of the process of normalization of bilateral relations, with greater or lesser effectiveness, may or may not benefit. Now the bases that are being configured tend to favor the most negative schemes in this direction.

Un breve análisis del momento actual

Un breve análisis del momento actual

Por Domingo Amuchastegui

18 de febrero 2021

De un tiempo a esta parte he insistido en que estamos en presencia de la gestación de lo que he llamado “la ruta de Navalny a la cubana,” entiéndase bien “a la cubana.” ¿Qué quiero decir con esto? Estamos en presencia -sin el comnponente de masas hasta ahora que se ha visto en Rusia ni una figura más eficaz que Navalny- de la maduración de iniciativas concertada en ambas orillas -y con financiamiento y auspicio del lado de acá- a fin de lograr la cristalización de una corriente o movimiento capaz de impactar negativamente la imagen de la Revolución cubana o lo que queda de ella a esta altura, con sus costos tanto internos como externos.

A los conocidos componentes de agudización extrema de la crisis del modelo cubano (probadamente inoperante en lo económico, el embargo sexagenario convertido en guerra económica por Trump más los múltiples efectos y costos de la pandemia), hay que añadir ahora otros no menos importantes. A escala internacional la ruta de Navalny se define como la opción más influyente -y más alentada- para erosionar la opción Putin desde EEUU y la UE. En el caso cubano se enfila primordialmente a debilitar la credibilidad internacional del Gobierno cubano y de fomentar a lo interno esquemas superiores de agitación y confrontación que agiganten a niveles nunca antes vistos los niveles de malestar y descontento en amplios sectores de la sociedad con tendencia a la hipótesis de explosiones socio-políticas del corte del llamado “Maleconazo.” Favorecen semejante escenario: a. Los niveles sin precedentes de la crisis actual; b. No avizorarse una salida o mejoría a corto ni mediano plazo; c. La gravitación del factor “Miami” ha crecido como nunca antes; d. Y un factor en extremo novedoso e influyente: la informatización acelerada en estos últimos tiempos con sus enlaces por medio de las redes sociales crean ahora niveles de información y comunicación que escapan a cualquier intento por controlarlas o anularlas.

No estamos ahora frente a los proyectos de la Fundación Cubano-Americano, de las Damas de Blanco, Payá, etc., etc. los que quedaron agotados y derrotados en el largo camino de los 90 hasta la fecha. El llamado Movimiento San Isidro puede parecerse a algunos de esos viejos intentos, pero se inscribe ahora en una perspectiva diferente. Lo son más todavía los incidentes ante el Ministerio de Cultura en términos de desafío y participación más numerosa. Episodios así era inimaginables en los 90. Ahora están ahí y, eventualmente, llamados a continuar y multiplicarse. Un hecho singular, a manera de novedoso hito, es el episodio de Patria y Vida, que no puede subestimarse en lo más mínimo tanto por su contenido como por sus efectos. Craso error será abordar estos novedosos contextos con las descalificaciones mediáticas habituales, operativos policiales o acciones violentas (para no recordar las brigadas de respuesta rápida). El momento es esencialmente diferente y demanda de parte de las autoridades cubanas respuestas económico-sociales, políticas y mediáticas enteramente diferentes que neutralicen estas tendencias y restablezcan en lo posible una mayor legitimidad.

Y de todo lo anterior -a fin de interrumpir “la ruta de Navalny a la cubana”- podrán o no beneficiarse el llamado “exilio histórico” asentado en Miami y aquellos que en Washington buscan impedir o reducir al máximo el que se retome con mayor o menor eficacia el proceso de normalización de las relaciones bilaterales y ahora las bases que se están configurando tienden a favorecer los esquemas más negativos en esta dirección.

¿Qué les parece? Sería útil compartir estas apreciaciones con algunos amigos por allá…

Un abrazo,

Chomin

Interview with Adriana Pérez

Interview with Adriana Pérez

I live proud of being a woman and Cuban

By Magaly Cabrales – Cuba | lajiribilla@cubarte.cult.cu

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

“As time goes by, you gather strength, willpower, resources and energy to face the new challenges that life imposes on you”. Photos: Courtesy of the interviewee. Taken from the family album

“Gerardo always taught me that: live each day as if it were your last. And that’s what I did.”

During the relentless struggle for the Five’s release, did you ever feel alone?

My life strategy was to prepare for the future day by day, even though I had no idea when it was going to come. But I still did what I could every day. Gerardo always taught me that: live each day as if it were your last. And that’s what I did, even though I felt that all the sentimental burden I was carrying was hardening me. I got so hard that I reached the last stage of the campaign terribly exhausted from a sentimental point of view. Despite that exhaustion, I found the strength to welcome Gerardo, Ramon and Tony when they finally arrived in their homeland on December 17, 2014.

“Just because of the perseverance (…) that characterizes Cuban women, I managed to get here with all my dreams turned into a beautiful reality”.

“Today, she says excitedly, she is immensely happy because ‘I have Gerardo and my children by my side'”. Photo: Taken from the Facebook profile GEMA – from Cuba.

Anesthetized by technology

Anesthetized by technology

No parent should be happy with this fatal prophecy, with the idea of raising their children to become manipulable automatons, only interested in fun and entertainment.

By Mary Luz Borrego, February 28, 2021 – 3:09am

By Mary Luz Borrego, February 28, 2021 – 3:09am

Master’s Degree in Communication Sciences. Specialized in economic issues. Winner of important awards in national journalism contests.

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

First, the technologies flirted. Then they dazzled us. Now they seduce and cajole us to open the way to a dependence that is perhaps as harmful as that of alcohol and cigarettes. Science has already begun to speak loud and clear about the harmful influence of their excess, particularly for children and young people born in the digital age.

Neuroscientist Michel Desmurget, Director of Research at the French National Institute of Health, recently published the book The Factory of Digital Cretins, where he offers ample evidence of how the current excessive use of screens and devices of this nature seriously affects, and for the worse, the neural development of the newest ones.

Too many hours in front of the TV, videogames, cell phones; too much time embraced to the Internet and the banality offered on a silver platter from social networks. The result? According to studies conducted in various parts of the world, for the first time, the so-called digital natives are the first generation in history with a lower IQ than the previous one.

Such information has been documented in several nations, even with remarkable socioeconomic stability such as Norway, Denmark, Finland, Netherlands, France, among others.

With technological dependence -say several international pieces of research -, the main foundations of human intelligence are affected: language, concentration, memory, general culture…; all impacts that, at the very least, inevitably lead to a significant drop in academic performance.

Quite a few Sancti Spritus parents can attest to this, after facing daily disputes with their children in this regard to get them to put down their phones and pick up their books, at least for a few minutes each day, in colloquial language.

And many parents, busy with their daily survival, have not even noticed that some of their children, either because they are clever or naive, have begun to sell or give away their identity on Facebook so that others can publish God knows what content, also presumably for a fee.

The cry in the sky at this time is not only because the addiction to digital media causes body ailments such as sedentary lifestyle, pain in the neck or back due to poor posture; because the screens can cause dryness and eye damage; because the headphones lead to deafness and even traffic accidents.

This barrage is not only related to the risks of someone manipulating an image or distorting personal data to denigrate another with physical or psychological harassment; to the alienation and avoidance of the problems that this excess of technology generates; to the emergence of models far from reality and linked to controversial prototypes of success and reputation; nor to the fact that these media are demonstrably used in the subversive war against Cuba.

It happens that now, in addition, experts assure that recreational screens underestimate the intellect and influence brain maturation, especially in the areas related to language and attention. In other words: the excessive use of digital media stultifies, affects writing and spelling, undermines the ability to think deeply and even turns children into half-wits.

It is not a matter of demonizing or renouncing the development and the obvious possibilities that technology offers by allowing access to a range of content not available to previous generations. It is essential to teach fundamental computer skills in schools, as the use of these options in a deliberate and balanced way can contribute a lot to teaching and research.

However, not infrequently, Saint Google makes it so easy for students to do research that they put aside logic and reasoning to copy any answer, without deciphering, composing, or judging the contents.

In truth, it is difficult to find a middle ground, especially during this last year, when social confinement has restricted sports and cultural practices; when it is known that children have at least their cell phones, televisions and computers at hand almost all the time; and not precisely for knowledge, but for impoverishing trivialities or recreational interests, seasoned with the distraction of endless alerts and notifications.

While it is true that during the months of pandemic these powerful digital tools have contributed a lot to work, study and socialization at a distance, it is also evident that circumstances have made humans increasingly dependent on technology.

According to international estimates, the hours spent in front of the screen vary with age, but before reaching the age of 18, children have spent the equivalent of three school decades in front of these media.

Based on the criterion that the fewer screens the better, experts recommend parents and teachers to use technology, but in moderation; to discuss its proven adverse effects with the new generations and to lead by example because it is often those who should be correcting this distortion who are the first to practice it.

France and some Asian countries have gone even further and have begun to legislate against these devices in childhood and adolescence because they consider that abusing them constitutes irresponsibility that young people will pay dearly for.

The worst theories predict that digital natives will not even understand computers well and will barely be able to use basic digital applications, buy products online, download music and movies, among other minor trades because they will grow up blinded by bland entertainment, incapable of thoughtful and intelligent attitudes, uncreative and not revolutionary at all.

Then, nothing seems more sensible than adult mediation to show, teach and guide the youngest in the fascinating world of technologies, with an eye to take advantage of their excellent advances in terms of personal growth, educational quality and intellectual development.

Without being alarmist, something urgent must be done because no parent should be happy with this fatal prophecy, with the idea of raising their children to become manipulable automatons, only interested in fun and entertainment, so that they act like mediocre fools, without dreams or thoughts of their own.

Tomasito, Between Books and Battles

Tomasito between books and battles

Tomás Fernández Robaina will receive the Distinction for National Culture today

Author: Pedro de la Hoz | pedro@granma.cu

March 4, 2021 23:03:32 PM

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

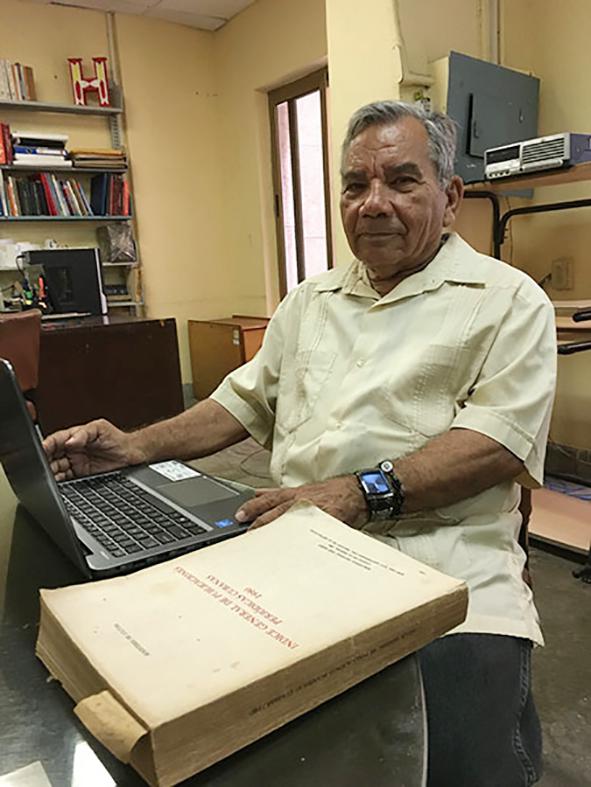

One fine day, looking for proximity between home and work, Tomás Fernández Robaina left behind his job as an accountant in a light industry establishment and joined the José Martí National Library. That was not a simple job exchange, but a radical change of life, because it was the beginning of the parallel takeoff of a substantive work in Cuban bibliography, and in the historical research related to the African legacy in national culture and the fight against discrimination because of skin color.

On the verge of 80 years of existence, five and a half decades of which he has spent at the prestigious cultural institution, Tomasito inspires respect and admiration for the impetus and passion he puts into every intellectual endeavor.

Those qualities nurtured the construction of one of his exemplary contributions to the field of island librarianship: the General Index of Periodicals. It was the result,” he recalled, “of an analysis of the indexes that had traditionally been prepared in the Library after the Revolution. As Salvador Bueno’s assistant, looking for information for the work I had to do in view of the popular literacy campaign, I realized that finding information was not very easy, because it was necessary to register a large number of directories. There were so many indexes that had been compiled that we really had to find a new way. I envisioned the project in two ways: to consolidate all the contents of the indexes that had already been compiled, and to begin to compile a repository that would include the contents of all the periodicals that were emerging”.

Having been the compiler of the Bibliografía de estudios afroamericanos (1969) and the Bibliografía de temas afrocubanos (1986) allowed researchers, professors, students and readers in general to have valuable tools of knowledge, and in his personal case, to confront sources that would be extremely useful for monographs and essays.

In 1990, one of his most far-reaching and impactful works, El negro en Cuba 1902-1958, was published. Although the author modestly stated that he was limiting himself to offering notes for the history of the struggle against racial discrimination, the documentation provided and the judgments derived from it, as well as the punctual record of the milestones, turn this essay into an essential reading.

Tomasito’s publications also include Hablen paleros y santeros, Recuerdos secretos de dos mujeres públicas, Cuba: personalidades en el debate racial and Identidad afrocubana: cultura y nacionalidad.

A member of the Cuban Association of Librarians (Ascubi) and of the Association of Writers of UNEAC-he is one of the most resolute activists of the José Antonio Aponte Commission-, Tomasito maintains, as a currency, to share what he has, to stimulate the spiritual growth of the new generations and never stop fighting to complete the work of social justice of the Revolution, especially with regard to the conquest of the fullest equality.

Inequality Exposed in the Face of Covid-19

Inequality also surfaces in the face of the pandemic

Immunizing their populations may be as difficult for many states as the COVID-19 scourge itself.

Posted: Saturday 27 February 2021 | 08:16:08 pm.

Author:  Marina Menéndez Quintero | marina@juventudrebelde.cu

Marina Menéndez Quintero | marina@juventudrebelde.cu

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

The arrival of Sputnik V was received with enthusiasm in the Mexican capital. Autor: @ClaudiaShein Published: 27/02/2021 | 07:48 pm

Assets, buildings and even military bases. What no country would put at stake, should serve as a guarantee against possible legal claims…

Abusive demands, some said; others sniffed out a hypothetical ulterior motive, and third parties even concluded that such far-reaching forecasts showed too much distrust of the manufacturer’s own product.

What is palpable is that the revelations about the unimaginable conditions that the pharmaceutical company Pfizer has imposed on Latin American countries in order to sell its vaccine against COVID-19, are a clear illustration of the concerns expressed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and by the UN Secretary General himself, about the difficulties that poor nations will have to face in order to immunize their populations.

“I must be frank: the world is on the brink of catastrophic moral failure, and the price of this failure will be paid in the lives and livelihoods of the poorest countries,” warned Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director general of the WHO, last month, drawing attention to the huge inequality in access to vaccines around the world.

UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres reiterated warnings about how inequity caused by the unfair global economic order and lack of cooperation will once again prey on the poor – now in the face of a deadly threat as direct as the pandemic – when he criticized what he called the “grossly unequal and unfair” distribution of the vaccine.

At that time, he pointed out, only ten countries had administered 75 percent of all the doses distributed worldwide, while more than 130 countries had yet to receive a single dose.

In this context, the revelations made public a few days ago by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) – a news organization dedicated to investigative journalism based in London – and the Peruvian media Ojo Público, based in Lima, about the difficult negotiations of nations such as Argentina and Brazil to acquire the vaccine produced by the pharmaceutical company Pfizer, acquire support.

Their harsh and unusual demands illustrate the additional obstacles that resource-poor nations, including those more solvent ones that have not produced their own vaccine, may face, beyond the lack of current money.

As the journalistic investigation acknowledged, “most governments offer indemnification (exemption from legal liability) to the vaccine manufacturers they buy from.”

That is, the government would pay for any lawsuits against the manufacturer that a vaccinated person might file. “This is fairly typical of vaccines administered in a pandemic,” he noted, even though adverse effects are very rare.

However, Pfizer’s demands for Argentina and another nation, whose representatives have remained anonymous because negotiations are continuing, went further, asking for additional indemnification against any claims, officials in Buenos Aires said.

After representatives of the southern cone nation had negotiated difficult requirements that demanded changes in its legislation, Pfizer went so far as to demand “that the sovereign assets be part of the legal backing,” said a participant in the negotiation.

This happened at the end of December. It involved the Argentine government putting up its sovereign assets – which could include federal bank reserves, embassy buildings or military bases – as collateral against potential claims.

“We offered to pay millions of doses in advance, we accepted this international insurance, but the last request was extraordinary (…). It was an extreme demand that I had only heard when it was necessary to negotiate the foreign debt; but in that case, as in this one, we rejected it immediately”, the source affirmed.

Similar conditions were imposed to countries such as Brazil, where there were no agreements until today.

According to a message on Twitter by Misión Verdad, nine countries in Latin America and the Caribbean have reached agreements with Pfizer.

Although the tweet states that “the terms of these commercial agreements are not known” -and in truth it is information that in many cases is confidential-, the investigation by The Bureau… and Ojo Público gives an account of the rigors faced by Peru, and the “set of binding conditions” that it had to sign to close the agreement.

These included a supreme executive decree by which the nation committed to submit to international arbitration if disputes arose in the contracts for the purchase of the lots. At the same time, Peru waived “the sovereign immunity of the State for the enforcement of an arbitration decision”.

Contacted by The Bureau…, Pfizer declined to discuss the ongoing private negotiations, but argued that it has allocated doses to low- and middle-income countries at not-for-profit prices, including an advance purchase agreement to supply up to 40 million doses to Covax: a UN-sponsored project, and the only one worldwide that aims to facilitate access to vaccines for poor countries.

Meanwhile, vaccines that were initially viewed with apprehension, such as the Russian Sputnik V, are increasingly being used in Latin American countries.

Although Mexico has also acquired the Pfizer vaccine, in a message published on Twitter on the 23rd, Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard thanked President Vladimir Putin, the Russian Foreign Minister and the Ambassador in his country “for their support in making possible the arrival of Sputnik V vaccines to our country. Mexico-Russia friendship grows stronger,” he wrote. More than 20 million doses arrived from Moscow, far exceeding the thousands of vaccines from other companies that had arrived until then.

It is known that Sputnik V has also been acquired by Venezuela, Argentina, Paraguay, Colombia and Bolivia. In Peru its acquisition has been recommended and it has been reported that Brazil is planning to buy it, while it was expected to arrive in Chile. Reports state that in Ecuador contacts have been maintained with suppliers.

Meanwhile, reports from the Russian Embassy in Mexico state that the Russian Direct Investment Fund is looking for allies to produce Sputnik V in that Latin American nation.

In the midst of so much selfishness, the purpose could be evidence of humanistic logic. Mexico is the second country in the Americas with the second highest death rate from COVID-19.

But there is no shortage of people who appreciate the growing presence of Sputnik V as an expression of Moscow’s growing influence in the region.

Cooperation is needed

One hundred and eighty nations have endorsed the Covax initiative, which needs the help of rich countries to provide the funds to buy the drug. Ghana became the first country to receive a batch this week.

However, the pace may be very slow. According to officials involved in the initiative, the aim through Covax is to be able to vaccinate just 20 percent of the most vulnerable population in each participating country by the end of this year.

The People’s Vaccine Alliance coalition, a network of organizations including Amnesty International, Oxfam and Global Justice Now, estimates that nearly 70 low-income countries could vaccinate only one in ten citizens.

The response from potential donors is still not registering at the required level. Dr. Tedros explained that vaccines can only be delivered to Covax member countries if rich nations cooperate and honor contracts, referring to commitments made by the United States and the European Union to significantly increase their contribution.

On the other hand, regional solidarity initiatives are trying to help and could be very effective if they were more generalized.

An example of cooperation actions that could help is provided by ALBA-TCP (Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America and the Peoples’ Trade Agreement), whose Bank announced in December – by the decision of the most recent Summit – the creation of a modest fund of two million dollars as financial relief to member countries that needed to acquire the vaccine and had not concluded negotiations with the supplying companies due to lack of money.

The availability or otherwise of the vaccine by all nations will be absolutely decisive in the planet’s triumph over the pandemic. Faced with COVID-19, we will either all emerge or we will all stagnate.

I have always been in favor of dialogue

I have always been in favor of dialogue

Feb 18, 2021

By Carlos Alzugaray Treto

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

NOTE FROM EDITOR OF LA TIZZA

NOTE FROM EDITOR OF LA TIZZA

At the request of its author and due to the interest that the ideas presented here are of interest to La Tizza, we publish the following text by Carlos Alzugaray Treto, an expanded and revised version of his comments during the round table discussion “Dialogue in Cuba today”, developed in social networks on February 11, 2021.

I thank Julio for the opportunity he has given me to participate in this workshop with the presence of several people I know and others with whom I share for the first time. And I thank him first because I have always been a supporter of dialogue and I have never refused to participate in any dialogue to which I have been summoned, especially if it has to do with Cuba, as in this case. I come in the spirit not only of speaking and sharing my reflections, but, more importantly, of listening.[1]

And, secondly, because it allows me to make known a series of personal reflections with which I have been grappling since November 27 last year, as a result of what happened at the Ministry of Culture that night. As some of you know, I live around the corner from that government institution, so when I say that these issues are close to me, I am not speaking in a metaphorical sense, I am also referring to a physical proximity.

It is clear that I belong to an older generation than the other participants in this workshop. Therefore, my life experience is not the same, which may inevitably lead to different conclusions. When I talk and exchange with the young people of today, I often compare what I had to live and do when I was close to the age of some of the participants here, between 15 and 35 years old (1958-1978), critical moments in the history of our country and its Revolution.

Among the events in which we were actors, participants or witnesses in a vivid way are the Bay of Pigs invasion, the October Crisis, the cultural dialogues of the 1960s – not only Words to the Intellectuals but also something so closely related to art in particular as the cinema debates – , sectarianism, the “Hard Years”, in the words of a collection of short stories by Jesús Díaz, Che’s “Socialism and Man in Cuba”, the Revolutionary Offensive, the magazine Pensamiento Crítico, the Tricontinental, the invasion of Czechoslovakia, the internationalist deeds of the Congo and Bolivia, the Padilla case, the Zafra of the 10 Million, the Gray Five-Year Period, the terrorist attacks against civilian targets such as the Cubana flight in Barbados and our Embassies and Consulates, the internationalist epic of Angola. In short, the list is long.

At that time, most of us young people went to the calls of the revolutionary leadership imbued with a spirit of sacrifice and discipline -words of order-, convinced that in this way we were defending national sovereignty, constantly threatened by the United States, and we were building a better future for our country.

There was no lack of dialogue then. There was discussion and debate.

Of course, the way of thinking of today’s young people is somewhat different and I recognize and accept that. I believe that the same patriotism and the same commitment to social justice persist in them, but there are differences. In 2009 I wrote an essay for Temas magazine, entitled “Cuba fifty years later: a meditation on continuity and political change in a new historical moment”. There I argued that an important change was that today’s youth, even the whole society as a whole cannot be mobilized in the same way and that the words of order are others: autonomy and prosperity.

I do not reproach, I simply note that this is the case. You will tell me.

This reflection on what in my view are the two major issues in the national debate or dialogue, how to achieve autonomy and prosperity in these difficult times, also leads me to reflect on the obstacles that stand in the way, and from my point of view the policy of the United States towards Cuba with its two main aspects: economic, commercial and financial blockade; and persistent interference in Cuba’s internal affairs still carries a lot of weight. The latter is not only the governmental action legislated in the Helms-Burton Act, but it has become the center of the political practice of many groups and individuals living in South Florida, who were and are friends or schoolmates and even relatives of those of us who are here. Believe me, something similar happened to us – I personally had a cousin and several school friends who lent themselves to the Playa Giron invasion – .

I know that many will disagree and put in first place actions of the Cuban government as the culprits of our difficulties. And they have a right to think so because they are not wrong, there have been mistakes. But I believe that the evidence is there, particularly during the last few years under the previous US administration which tried, by all means at its disposal, to aggravate all the contradictions and internal tensions to achieve what was proposed in April 1960 in the infamous Mallory Memorandum: “to produce hunger, desperation and the overthrow of the Cuban government”. Even after losing the elections on November 3, that administration continued to sanction Cuba until shortly before the handover of power, and continued to grant funds to stimulate a social outbreak in our country.

So, even though I know that the new administration may change things and return to Obama’s policy, this is something that cannot be forgotten in any dialogue or political action today.

And this argumentation, which I do not ask to be shared, but to be considered, leads me to the main point I want to make in this pronouncement which is at the same time very personal. As it is common knowledge, I was among the signatories of the first document of “Articulación Plebeya”. I did so on Saturday morning, November 28, when it seemed that the dialogue requested after the San Isidro incidents had come to fruition. My purpose was to support that dialogue. Like Fernando Perez, I thought that I was traveling to the future.

I am one of those who think that some of the demands that were presented by the 30 who participated in that early morning meeting, related to Decree Law 349, are legitimate. In fact, if I were the Minister of Culture, I would have asked the President a long time ago to repeal that decree and would have summoned the whole intellectual community to a deliberation exercise to draft together a new one, or several, because, in my opinion, a defect of Law 349 is that it wanted to cover too much and in different fields.

The experience since November 28, and in particular what happened after January 27, reveals a bitterness and intolerance that is regrettable. I believe that, together with efforts to put dialogue on track by sectors in the government, there have been and there are also unacceptable mistakes and practices by others within the government that I respectfully invite to reconsider. But I also perceive that among those who call for dialogue there are behaviors of defiance and confrontation, which do not foster trust and facilitate the work of those who do not want dialogue. I am not going to point the finger at anyone. I am only inviting to reflect.

But the most serious thing for me is the perception that, stimulated by some external actors, they are not seeking an understanding but a protagonism that makes them visible in certain social networks, at a time when the country is facing four much more important challenges that I will enumerate:

1. Confronting the pandemic, in the face of which thousands of young Cubans risk their lives, on a daily basis, trying to save other lives. This is not a slogan, it is a reality and one that forces us to see things with more humility. There is a permanent dialogue between the government and the scientific and health community to find ways to solve this existential challenge. This is a dialogue that can be an example to be imitated.

2. The financial order that implies the transition to an economy with different rules of the game. Millions of Cubans are now struggling with salaries and pensions that are not enough for them, as well as having to wait in long lines. And yet, there are citizens who dialogue with the government, which has modified many policies after listening to them, such as, for example, electricity rates.

3. The expansion of self-employment, late and with many shortcomings, but which has also been the result of a dialogue between the government and the self-employed and economists who, with tenacity and patience, have been insisting on it over the years.

4. The transition from a confrontational relationship to one of understanding for the normalization of relations with the United States. This will not be an easy transition, although it is likely to end in a more favorable climate than the one that has prevailed. Supporters of what Mallory called the “overthrow of the government” in Cuba through hunger, desperation and social outbreak are relentlessly trying to influence the Biden administration to continue applying sanctions and funding these groups in Miami. 2] On this issue, the dialogue must go through something similar to what a group of people from civil society did several days ago with the leadership of the Editorial Board of La Joven Cuba to produce the Open Letter to President Joe Biden, which was published the day before yesterday and which several of us here have signed. This is an example of something that can be done to seek changes and that involves dialogue within civil society.

I think that relations with the United States are a key issue. Because the dialogues in Cuba today are crossed, whether we like it or not, by the problem of the relationship with our neighbor to the North, where close to 2 million Cuban brothers and sisters live.

By the way, a dialogue that has been postponed due to the pandemic but that the government has already expressed its willingness to have, is the dialogue with the emigrants, who are also part of the Nation and whose rights should continue to be expanded if there is a climate of understanding with the government of the country where most of them live.

For these reasons, I asked myself and I ask myself if I can continue to support in all conscience that document that I signed on the morning of November 28, which had the shortcoming, among others, of only touching on this subject in passing.

That document was modified, I was even asked for contributions and I gave them, but I have no longer signed the two new documents produced by Articulación Plebeya. I do not repudiate my signature. It is there. But I have decided to refrain from signing any other document of this Platform. It has seemed to me that for a problem of elementary loyalty to its promoters I should have come here today to say this, among other things.

I end this presentation with the following proposals:

1. Recently Professor Carolina de la Torre proposed in the social networks a truce. I support her. Let’s seek a truce while we deal with at least the first challenge I referred to: the pandemic. If the predictions of our scientists come true, and there is no reason to doubt it, vaccination of the entire nation will begin in the second quarter. Let us give ourselves that time.[3]

Jurgen Habermas has elaborated a whole reflection on deliberative politics. There is a development of this modality of democratic procedure. There is a literature. Studies have been done. It has even been exercised with good results in other countries. The Cuban government has practiced it on occasions, perhaps imperfectly, but with important elements, such as when it submitted to deliberation or popular consultation the Social Security Law, and the guiding documents of its entire policy – Update, Conceptualization, Vision and Strategy 2030, and the Constitution -. Raúl Castro himself acknowledged this procedure when he stated a few years ago that the best decisions come out of the broad and deep discussion of the possible policies to be approved. In Cuba there are experiences of dialogue platforms, such as Último Jueves de Temas, Dialogar Dialogar of the AHS, or the Workshop on Socialism and Democracy of the ICIC “Juan Marinello”. Therefore, it should not be difficult to organize something like this with respect to Decree 349. Submit it to a broad deliberative consultation for which UNEAC and AHS can play a role.

Let us take advantage of the truce to organize it.

Thank you very much.

Thank you very much for reading! You can find our contents on our Medium site: https://medium.com/@latizzadecuba. Also, on our Twitter (@latizzadecuba), Facebook (@latizzadecuba) and our Telegram channel (@latizadecuba) accounts.

Feel free to share our publications and forward them to your acquaintances!

Notes:

[1] All footnotes are after the February 11 discussion.2] Such is the case, for example, of a letter that has been circulating since Monday 15 and which was published in the journalistic site Cibercuba, with a clearly destabilizing and tendentious orientation. It is self-titled Cuba-US Letter, but it is also known as the Cibercuba Letter and is full of lies and half-truths, all aimed at hindering the process of normalization of relations between Cuba and the United States. Those who have signed it are playing into the hands of the policy of regime change with prejudice pursued by the previous U.S. administration. It can be seen on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=109941937799814&id=108337137960294

3] I clarify, in case there is any confusion, that the truce proposed by Professor de la Torre and which I fully support in this way is a total truce that should include each of the actors involved in this process, the government, the N27 group, the official national media and the alternative media, both based in Cuba and abroad.

=================================================

In 2009, Temas magazine published an extended commentary by Dr. Alzugaray entitled Continuity and Change in Cuba at 50. This essay was embedded in the version of THIS essay that appeared on La Tizza. It was also published, in English, in the journal Latin American Perspectives. Dr. Alzugaray has kindly shared the English version which appeared in Latin American Perspectives.

It is available here: https://walterlippmann.com/continuity-and-change-in-cuba-at-50/

Continuity and Change in Cuba at 50

Continuity and Change in Cuba at 50

The Revolution at a Crossroads [1]

Carlos Alzugaray Treto is a professor at the Center for Hemispheric and United States Studies of the University of Havana, a member of the Cuban Academy of Sciences, and a former ambassador to the European Union.

Translated by Victoria J. Furio

After Fidel Castro’s retirement from his main governmental positions, Cuba finds itself at a crossroads. Two main challenges emerge, one economic and one political. The economic one arises from the need to design a productive system that resolves the imbalance between workers’ salaries and the actual distribution of basic goods and the imbalance between different sectors of society without destroying the revolution’s social achievements. The political one must deal with the creation of a new form of governance and consensus building in the absence of the revolution’s founder and leader. The changes to be introduced require the broadening of democracy. These challenges entail a national deliberation process during the Sixth Congress of the Cuban Communist Party that will identify several fundamental issues.

Keywords: Cuba, Socialism, Political change, Democracy, Transition

What must be done at any given moment is whatever that moment requires.

—José Martí

Revolution is a discernment of the historical moment; it means changing everything that needs to be changed.

—Fidel Castro

Fifty years after the successful rebellion against Fulgencio Batista’s dictatorship and the start of the transformation process generally referred to as “the Revolution,” Cuba finds itself once again at a momentous crossroads. On the eve of his eightieth birthday, having governed for almost half a century, Fidel Castro temporarily transferred his duties as head of state to his constitutional successor, General Raúl Castro, on July 31, 2006, because of a serious illness. What was originally projected as a difficult and painful recovery process requiring several weeks of absence resulted in a definitive retirement. Some 19 months later, on February 24, 2008, the newly elected Seventh Session of the National Assembly of People’s Power appointed a new government, led up to that point by the interim president. A few weeks later, on April 28, during the Sixth Plenum of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party, in which that organization’s Sixth Congress was officially convened, Raúl Castro (2008b) stated: “The agreements we have approved close the provisional phase initiated with the Commander-in-Chief’s Proclamation on July 31, 2006, and ending on the eve of February 24, 2008 with the message in which he expressed his desire to be only a soldier of ideas.” This has opened an uncharted phase in recent Cuban history in which Fidel Castro has ceased to be the head of state and/or government for the first time since February 1959, when he assumed the role of prime minister, later becoming “Compañero Fidel.” At this writing, however, he retains the position of first secretary of the Cuban Communist Party’s central committee. This historic moment for Cubans raises the prospect of inevitable changes and the associated uncertainty.

THE CROSSROADS: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE

This essay is an attempt to reflect and meditate on continuity and political changes—on the challenges and opportunities of this period and their significance. My intention is not to pontificate or point to inevitable paths. Nor do I wish to propose fixed alternatives, because the issue requires reflection that is open to dialogue, debate, and deliberation.[1] My essay is part of the process—also essential—of contributing from a social science and in particular a political science perspective to the national consultation launched by President Raúl Castro’s speech on July 26, 2007. As Julio Carranza (2008: 147) has put it, “Scientists and scientific institutions have a responsibility for public service, which consists of communicating specialized information and analysis directly to society not as political proposals but as well-founded interpretations that contribute to improving culture and public awareness on a variety of issues.”

The hypothesis that is the essay’s point of departure is that a predictable process of evolution toward new ways of governing Cuban society has begun. It is not what current political science has called a “transition” (giving rise to a whole school of “transitology”),[2] although the need for adjustments, transformations, and changes within continuity may correspond to a broad sense of this notion.[3] Paradoxically, the use of the concept of political and social transition appeared well before the current trend, being used in the Marxist literature to refer to the evolution of socialist society from an initial to a more advanced stage (Marcuse, 1967: 37–54). Today, however, the concept is too “loaded” and presumes “regime change” and, more important, the enthronement of political systems that Atilio Borón (2000: 135–211) has called “democratic capitalism” in societies previously governed by regimes labeled “authoritarian” or “totalitarian.” Cuba’s situation does not fit this description; neither its starting nor its ending point matches those of the political transitions most frequently analyzed in the current literature.

Some writers have insisted on labeling as “transitions” the processes of reestablishing capitalism in former socialist or European “popular” democracies, although it is appropriate to acknowledge that “transitions” has also been used to refer to the replacement of once-dictatorial, right-wing regimes in southern Europe (Spain, Portugal, and Greece) and in Latin America and the Caribbean in the 1970s by governments chosen through so-called free, competitive, and democratic elections (O’Donnell, Schmitter, and Whitehead, 1986; Huntington, 1991; Przeworski, 1991; Alcántara, 1995; Linz and Stepan, 1996). In many cases (as in that of Spain) the concept of “transition” has a positive connotation. In Cuba’s case, use of the term could cause additional misunderstanding because it is endorsed by a subversive and antinational project of the University of Miami, financed by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and in the designation by the United States of a so-called transition coordinator within the interventionist program detailed in the Assistance to a Free Cuba Report adopted by the Bush administration in 2004 and renewed in 2006.[4]

The fact is that Fidel Castro has governed Cuba in a way that for obvious reasons cannot be replicated. Some leadership sectors in Cuba have affirmed on more than one occasion that Fidel’s absence will change nothing, to the point of including in the Constitution the idea that socialism is irrevocable.[5] This is a reaction that can be logically explained by the need to emphasize the continuity of the project begun on January 1, 1959, as a counterweight to attempts to reverse it from the outside, precisely by the superpower that has most interfered in internal Cuban affairs, the United States (Alzugaray, 2007). This caution notwithstanding, it is obvious that changes must be made in politics and governance, although these changes will be a response to an internal dynamic rather than to demands coming from outside as has happened throughout Cuban history. This principled position, for which popular support is evident, was advanced on July 11, 2008, by President Raúl Castro: “I reiterate that we will never make a decision─ not even the smallest one!─on the basis of pressure or blackmail, no matter what its origin, from a powerful country or a continent” (2008c)

These changes are taking place, as they always have in Cuba, in the context of clear continuity, shattering preconceptions. This situation raises questions about the Cuban nation’s likely future in these new extreme circumstances. Calculations and conjectures are appearing, especially outside of Cuba, that are based on what appear to be similar processes in recent history. Once again, Cubans will probably provide their own responses to the current challenges, stamping their own imprint on the future—taking “the road less traveled” as in Robert Frost’s famous poem.[6]

FIDEL CASTRO, THE REVOLUTION, AND THEIR PLACE IN HISTORY

The Cuban Revolution, creator of the political regime currently governing events on the island, was a necessary and original process. The need for it, in historical terms, was born of what could be called the four great national aspirations thwarted since the nineteenth century: sovereignty, social justice, sustainable economic development, and autonomous democratic government. The triumph of the revolution in 1959 was the result of specific internal circumstances and not, as with socialism in Eastern Europe (with the exception of the USSR) of foreign imposition.

After 400 years of Spanish colonial oppression and 60 years of U.S. domination, the Cuban people and its progressive political and social sectors had long demanded a truly free and sovereign nation. The recovery of national self-determination was therefore one of several driving forces—perhaps the leading one—in the process of radical change initiated in 1959. By that time it was clear that the principal obstacle to self-determination and national sovereignty was U.S. imperialism’s hegemonic designs on Cuba (Pérez, 2008).

Another vital demand of Cuban society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was social justice—the country “including everyone and for the good of all” that José Martí demanded. The nation was ill; it suffered from unbearable inequalities and inequities that the ruling oligarchy happily ignored.

Third, the political system created in the shadow of U.S. hegemony had demonstrated not only its total inoperativeness but also a perverse tendency toward venality and corruption. Throughout Cuba’s brief postcolonial and prerevolutionary history, between 1902 and 1959, three dictatorships (those of Gerardo Machado from 1925 to 1933, Fulgencio Batista (behind the scenes) from 1933 to 1940, and Batista again (now openly) from 1952 to 1959, had revealed the total inability of Cuba’s political class to generate a sustainable democratic capitalism. Worse yet, government largely amounted to political dishonesty and immorality. The few administrations produced by elections, rarely free and fair, were known for theft and embezzlement of the public treasury to such an extent that in 1952 the Party of the Cuban People, favored by the popular majority to win the elections derailed by Batista’s March 10, 1952, coup d’état, had a broom as its symbol and the slogan “Shame on Money.” Because of this, one of the unfulfilled demands of Cuban society was for “good government”—responsible, efficient, and honest public administration.

Lastly, and above all at the middle-income and professional levels, there was a need to transform the national economy. Although cold statistics reflected a relatively high economic level compared with the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean, three factors were worrisome. Cuba was a mono-producing and mono-exporting country whose wealth depended almost exclusively on one item, sugar, and one market, the United States. Martí had warned against such a situation, arguing that “the nation that purchases rules.” The great disparities in income and well-being dissolved any satisfaction over the gross domestic product (GDP), and, as a result of the intimate ties with the neighbor to the north, Cubans did not compare themselves with the rest of the region. Their reference point was the highly sweetened image of the “average American” conveyed to the island by the constant cultural and ideological presence of U.S. consumption models. And, finally, the vulnerability of an underdeveloped economy was a source of constant concern because of its dependence on the fluctuations of the world market, always unstable with regard to sugar and other staples of the developed capitalist world produced in what we now call the Global South.

The outstanding political success of Fidel Castro during his 47 years of governance was precisely his ability to lead the nation toward achieving these four historical aims. While not all of these demands have been met in optimal form and degree, there is no question but that Cuba’s situation today reflects a radical change from that of 1958. There is also no doubt that this change took place in the direction desired by the populace and its political vanguards despite the obstacles placed in its way, especially the constant hostility of its powerful neighbor, the United States, whose policy of “regime change” toward Cuba is almost a half a century old.

To illustrate this point, a lengthy citation of the Cuban-American Harvard University professor Jorge Domínguez (2008), a source hardly considered a supporter of socialism or of the prevailing model on the island, may be worthwhile:

“To honor another honors ourselves”: a noble quote from José Martí that entered the Cuban cultural vocabulary more than a century ago. Let us honor Fidel Castro, then, as we observe the twilight of his life, not only those who supported him, but also those, like me, who did not. He was the one who transformed a people into a nation, who decisively modernized the society, who best understood that Cubans wanted to be “people”, not just appendages of the United States. He was the one who understood that its hypochondriac population needed more doctors and nurses per square centimeter than any other on the face of the earth. He was the architect of a policy of investment in human capital, which transformed Cuban children into the Olympic champions of Latin American education and which, therefore, allows us to envision a better future for Cuba. He designed a policy that allowed Cubans of all racial characteristics to have access to public health, to education, to the dignity that belongs to every human being, to the right to think that I, my children, and my grandchildren, whatever the color of their skin, deserve the same respect and opportunities as everyone else. He was not the one who invented the idea that women had equal rights in society but was a promoter of gender equality in citizen endeavors.

He was the author of a gesture that humanity is thankful for: to have risked the blood of his soldiers for the noble cause that powerfully contributed to preventing the racist South African apartheid regime from expanding into Angola. It is also he who deserves recognition for contributing to ending apartheid in South Africa, to the independence of Namibia, and to defending the independence of Angola. The day that Fidel dies, the flags of those African countries should be lowered in national mourning.

It is highly improbable and indeed implausible that the Cuban people and its leadership would voluntarily and consciously abandon and renounce the achievements of these 50 years. Nevertheless, Fidel Castro’s successors face serious challenges in reproducing the system without him. The reversibility of the Cuban revolutionary process as a result of internal mistakes and not from outside pressure was dramatically presented by Fidel Castro himself in his speech to the university of November 17, 2005 (F. Castro, 2005; Guanche, 2007).[7]

Among the strengths of the Cuban political regime in its current structure is, first of all, its high degree of internal and external legitimacy. Externally, this legitimacy stems from the well-known Cuban activism in the international arena and the broad network of foreign relations that has allowed the country to head the Movement of Non-Aligned Nations twice and to achieve a series of successes in the United Nations General Assembly on a resolution condemning and calling for an end to the U.S. blockade of Cuba. Having neutralized the policy of international and diplomatic isolation of Cuba begun by the Eisenhower administration and continued through the recent Bush administration has been one of the most important victories of the Cuban revolutionary leadership.

Internally, in addition to the majority recognition of what have been called the “conquests of the revolution,” legitimacy is conferred by an institutional framework upheld by two basic pillars: the Communist Party of Cuba and the Revolutionary Armed Forces (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias—FAR). It is a very common error in foreign spheres, especially among political scientists and analysts, to assume that the Cuban Communist Party is copied from similar ones in the Eastern European socialist countries. Despite the fact that the party’s leadership has committed widely acknowledged and/or rectified errors and that some methods and work styles—such as excessive centralism—bear the mark of their origins in the Soviet political model persist, in reality the Cuban revolutionary leadership has concerned itself, among other things, with two central aspects: the role as political vanguard of the activists who must be and have been at the forefront of any sociopolitical initiative and the struggle against any instance of corruption in its ranks. The honesty, simplicity, and sacrifice promoted by Che Guevara and not the privileges and benefits of a nomenklatura, as in the USSR and Eastern Europe during the socialist years, have been the paradigm of Cuban Communist behavior.

The influence of the provincial party leadership is also significant, as it is the most important sector of governance at the local and regional levels, in close coordination with the bodies of People’s Power (the provincial and municipal assemblies). Although this system generally functions satisfactorily, the contradiction must be pointed out that at the provincial and municipal levels, much more so than at the central level, the party openly and unapologetically plays a hegemonic role. At those levels, the first secretary of the local party committee is undoubtedly the most important political figure in the area, even formally assuming the presidency of the defense councils, the highest government bodies in cases of natural disaster or war. At the central level, however, it is much clearer because of the overlap of the positions of president/vice president with those of first/second secretary of the party.

Nevertheless— and this is an important challenge— we are still far from achieving a truly democratic culture. As Aurelio Alonso (2007) has pointed out, “The Leninist proposition of ‘democratic centralism,’ as a formula for proletarian power, has ended up establishing the centralist line for decisions and the democratic one for support when its merit would lie in all centralized action’s being subject to what is decided democratically.” In too many leaders there seems to be a common perception that the only purpose of debate is to convince the population that the course of action designed by the higher authorities at any given time is the only truly revolutionary one. “Bold attempts at analysis outside official discourse are stigmatized as immature, naïve, gullible, or simply provocative” (Fernández, 2007). According to the political discourse of many leadership cadres, those who dare to do so “are not adequately informed,” but the required information is unavailable because “disseminating it might be useful to the enemy.” Sometimes the paternalistic reproach is heard that anyone who disagrees or dissents is “naïve.”

In addition, Cuba has lacked a real culture of debate, dialogue and deliberation. Jesús Arencibia Lorenzo (2007) has identified seven “bricks” that obstruct the path toward truly productive deliberation within the national project: fear of risk, the siege syndrome, monopoly on information, unintelligible ambiguities, extreme puritanism, comprehensive planning, and the language of tasks.

Lastly, the need to defend the conquests of the revolution from imperialism’s increasing aggressiveness and the practices of property nationalization and centralization of the decision-making process over the years have led to what Mayra Espina (20070) has called the “hypernationalization” of social relations: “centralization, verticalism, paternalism/authoritarianism, distributive homogenization with insufficient sensitivity in dealing with the diversity of needs and heterogeneous interests (of groups, territories, localities, etc.).” On occasion one perceives a transformation of the relation between average citizens and those officials, also ordinary citizens, who hold some position in the state apparatus. These bureaucrats act more like bosses giving instructions on what can or cannot be done and enjoying that role, than like persons at the service of the people and subordinate to them. As early as 1963 Raúl Roa identified bureaucracy as “one of socialism’s worst stumbling blocks” (1964: 590).

NEED FOR ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL CHANGE

In the absence of Fidel Castro’s power to mobilize and to build consensus, the need for a mind-set of respect for dialogue, debate, and deliberation will increase. It will entail strengthening real collective participation and the construction of what could be a democracy that is both participatory and deliberative. Some form of debate was not completely absent in the past, but it was always subject to the ultimate authority of Fidel Castro, who frequently circumvented it in order to create a consensus that often became unanimity.

It is impossible to discuss alternative democratic models here. Most of the left has contrasted “participatory democracy” with the traditional “representative democracy” typical of capitalism and its political institutions. The latter was closely associated with the idea of “procedural democracy” first presented by Schumpeter (1954) in his classic Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, with the addition of the requirement of deliberation and the idea that citizens should not only participate in making or implementing political decisions but also contribute to their design through a rational and informed dialogue about the possible options.

The concept of deliberative democracy has been the object of significant debates in contemporary political science. The promoters of this idea (Gutmann and Thompson, 2004: 3) have emphasized that in essence, it means the need to justify the decisions made by citizens and their representatives. It is expected that both will justify the laws to be enforced. In a democracy the leaders must therefore explain their decisions and respond to the points raised by citizens as retorts. But not all matters require deliberation all the time. Deliberative democracy opens up space for other forms of decision-making (including negotiations and agreements between groups and secret operations ordered by executives), as long as these forms are justified at some point by a deliberative process. Its primary and most important characteristic, therefore, is the requirement that explanations be given.

The FAR and its important sister institution the Interior Ministry (responsible for the country’s internal security but closely linked in its origin and composition to the Rebel Army, predecessor of the FAR), constitute the most effective and prestigious of the institutions created by the country’s historical leadership. Their popular origin, continual involvement in people’s problems, historic contribution to the country’s defense and the liberation of other peoples, and economic pragmatism, demonstrated by the introduction of “business perfection” into their industries, allow them to enjoy the trust of broad sectors of the population. The upper echelons of the armed services have amassed a tradition of heroism, pragmatism, reliability, and professionalism not often seen in Latin America and the Caribbean or in the world.

Cohesion between these two institutions, which must be constantly nourished, will depend on the prevailing tendencies in other important leaderships in Cuban society. On the one hand we have the important business sector, composed in part of high-level FAR officers but also of a young generation of economists and administrators. One might presume that there is a desire in this sector to maintain consensus, but within it we find demands for the flexibilization of economic policy also present in the upper-echelon military although for different reasons. Among the former, it arises from concerns about administrative effectiveness; among the latter, it is also due to the need to maintain social stability. It is not a question of establishing a market economy but rather one of adopting initiatives that grant more autonomy to administrators, as set forth in the business- perfection program begun in the military-industrial sector. The ultimate goal is to stimulate production and develop the productive forces. It also has to do with creating more opportunities for individual initiative, a concern dating to the reforms that lifted the country out of the Special Period in the mid-1990s. These demands have begun to be expressed publicly in several recent scientific works (Monreal, 2008; Sánchez Egozcue and Triana, 2008; Everleny, 2008).

Traditionally, youth, especially students, have had a central role in Cuban politics. Almost all of the high-level leaders in the country were members of and had their first schooling in public participation in the Federación Estudiantil Universitaria (University Student Federation—FEU). In recent years, this organization, along with the Unión de Jóvenes Comunistas (Union of Communist Youth), has been among the pillars of the social programs promoted by Fidel Castro. Its role in the transformation period, which will inevitably affect Cuban society despite growing demands for greater leadership opportunities, will have to take the policies articulated by the other leaderships into account. The difficulties of this process are not lost on the various social actors, as Carlos Lage Codorniú, former FEU president, noted in a symposium sponsored by the magazine Temas: “It is not about lack of communication, but there are many new ideas that must be allowed to be expressed. And ultimately, it is we young people who are responsible for this shortcoming. In order to strengthen the weight of the young generation we must push, be more visible. Some sectors have recognized the need for young people to take part, but others still have great reservations” (Hernández and Pañellas, 2007: 160).

The organizations that serve the working class and campesinos will tend to seek new positions within the structure. Under Raúl Castro they will foreseeably be afforded more leadership precisely because of the need to develop a new national consensus. Such is the case of the recently initiated process of granting lands in usufruct with a view to increasing food production, in which the Asociación Nacional de Agricultores Pequeños (National Association of Small Farmers—ANAP) has been playing an important role. (Granma, July 18, 2008; Lacey, 2008). For its part, the growing role of the Central de Trabajadores de Cuba (Federation of Cuban Workers—CTC) was demonstrated by the year-long national consultation on the new social security law that preceded its approval by the National Assembly in its final session of that year (Valdés Mesa, 2008). While there is no doubt that this process provided the opportunity for broad debate, the unanimous adoption by the Assembly was not a true reflection of the divergent opinions that existed.

Lastly, the Cuban intelligentsia, recently affected by the memory of the “gray quinquennium” (the phase in which the USSR’s cultural policy of the early 1970s was copied), will seek greater levels of autonomy and freedom while defending its commitment to the core objectives of Cuban society. This was evident in the recent congress of the Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba (Union of Cuban Writers and Artists—UNEAC), which was an important example of deliberative democracy and of opening spaces for dialogue and public debate.

ECONOMIC CHALLENGES

The most important internal challenge that the leadership initially headed by Raúl Castro will face will be to resolve the increasing demand for salaries and legal income that are sufficient to permit all Cubans to cover their most important daily necessities. As a result of the crisis of the 1990s and the economic policies adopted, two significant equilibriums prevailing until 1989 were shattered. One was the balance between people’s incomes and the prices of basic goods, in some cases rationed and in others subsidized by the state budget. The disappearance of the mutually advantageous relations with the Soviet Union and the socialist camp knocked this plan out the window.

The other equilibrium that unraveled during the Special Period was the one existing among the various sectors of the population. Although Cuba abandoned its egalitarian policies in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a healthy tendency not to allow excessive inequality persisted. With the reforms introduced in 1993–1994, this balance disappeared; inequities arose that were the more unbearable because of the previous disparities between salaries and their purchasing power and the fact that many of these disparities were the result of illegal and corrupt practices.

Most Cubans aspire to maintain current levels of social security but would like to see Marx’s formula “from each according to his ability and to each according to his work” applied. This precept is not being fulfilled today. Although it is very difficult to determine the degree of national agreement on the issue, it can be said that Cubans, while maintaining an essentially socialist economy, would like to see more opportunities for prosperity, even at the cost of privatizing certain sectors.

This, of course, is nothing new. In 1973, during his speech on the twentieth anniversary of the July 26, 1953, assault on the Moncada garrison, Fidel Castro underlined it. After pointing out the need to “valiantly rectify” the “errors of idealism that we may have committed in handling the economy,” he stressed that communism “can only be the fruit of a communist education of the new generations and the development of the productive forces.” He continuted: “We are in the socialist phase of the revolution, in which, because of the material realities and level of culture and consciousness of a society that has recently emerged from capitalist society, the appropriate means of distribution is the one proposed by Marx in his “Critique of the Gotha Program”: from each according to his ability, to each according to his work!” (F. Castro, 1973). In his July 26 speech 35 years later (2008d), President Raúl Castro called this statement “fundamental”: “This speech, in addition to being a solid analysis of the past and present at the time, constitutes an accurate and precise appraisal of the harsh realities ahead and the means to deal with them.”

The situation described has led many Cubans to supplement their salaries with illegal activities in the so-called informal sector of the economy. This and none other is the root of the growing corruption at the lower and middle levels of business and services. The Cuban leaders have only recently understood that this is the most serious threat to the sustainability of the Cuban project, as Fidel Castro himself acknowledged in his speech to the university of November 17, 2005 (F.Castro, 2005). Nevertheless, despite some salary increases and other measures, the impression is that government responses are insufficient. The ideological consequences of the persistence and expansion of this phenomenon are the system’s greatest weakness.

This weakness is now intensifying. First of all, for the third consecutive year a GDP growth rate of more than 10 percent has been announced, creating even higher expectations, as yet unfulfilled, regarding personal prosperity for each individual. Second, Fidel Castro’s foreign policy involves increasing Cuban involvement in South-South cooperation, especially in the health sector, with repercussions at various levels. For example, in the medical arena there is a perception that domestic attention is being sacrificed in favor of international solidarity. Third, Cuba’s principal strategic allies in this phase, China, Venezuela, and Vietnam, albeit under different conditions, are implementing economic policies that provide more opportunity for individual initiative in achieving personal well-being.

In sum, in order to understand the need to deal with corruption and lawlessness and to preserve the revolution, we should recall an admonition of José Martí: “Being good is the only way to be fortunate. Being learned is the only way to be free. But, most often in human nature, one must be prosperous to be good” (1991 [1884]: 289).

The events of the past two-plus years since Fidel Castro’s illness and convalescence show that modest but solid changes are occurring in politics and in the search for solutions to the above-mentioned challenges. It is not just that Raúl Castro prefers to stress collective leadership rather than Fidel Castro’s high level of public and discursive leadership. Rather, as Cuba’s highest official, he has been developing and promoting a series of policies that go to the heart of the problems being faced by the country.