Movies 28

Tom and Jerry Turn 80

Tom and Jerry Turn 80

February 15, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

he hilarious Tom and Jerry, the cat and mouse, are silent characters.

This is the 80th anniversary of the release of one of the most famous cartoons of all time: Tom and Jerry.

How did this story come about? The plot is simple: fed up with the mouse that wanders around his house, a cat sets up a plan to throw him out with a trap loaded with cheese.

But the mouse, who is very lively, manages to get his favorite food out without any problem and then continues to walk around the corridors – and rooms, and so on – very happily. The cat insists on catching him, but always fails.

The friendly animal duo was created, as they say, in a moment of desperation.

The animation department of the Metro Goldwyn Mayer Studio (MGM), where the creators William Hanna and Joseph Barbera worked, had tried unsuccessfully to imitate other studios that had created successful characters like Mickey Mouse and the Porky Pig.

The animators, both under 30, began to think of their own ideas.

Barbera said he liked the simple concept of a caricature of a cat and mouse, with conflict and persecution, even though it had been done before.

Puss Gets the Boot (translated into Spanish as “El gato se gana el zapatazo”) was the first animated short film they released in February 1940.

The debut was very good and earned the studio an Oscar nomination for best animated short.

And the success deepened when a letter arrived from an influential figure in the entertainment industry from Texas asking when he was going to see another one of those “wonderful cat and mouse cartoons.”

Jasper and Jinx, as they were originally called, then became Tom and Jerry.

According to Barbera, there was never any discussion about the characters not talking.

Having grown up with silent films starring Charlie Chaplin, the creators knew that the cat and mouse could be fun without any dialogue.

The music, composed by Scott Bradley, highlighted the action of the plot, and Tom’s “human” cry was played by Hanna himself.

For most of the next two decades, Hanna and Barbera supervised the production of more than 100 of these short films.

In the world, these Tom and Jerry films are considered the best, because of their excellent hand-drawn animation.

In the mid-1950s, when producer Fred Quimby retired, Hanna and Barbera took over the MGM cartoon department. It was a time of budget cuts.

Tom and Jerry is still very popular around the world. It can be found on children’s television everywhere from Japan to Pakistan, and a new game about them for cell phones has over 100 million users in China.

(With information from La República)

Cuban Film Critic Praises Recent Lesbian Films

Elisa and Marcela, Marianne and Héloïse, Jean and Lydia

Elisa and Marcela, Marianne and Héloïse, Jean and Lydia

By Julio Martínez Molina

February 8, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

https://walterlippmann.com/elisa-and-marcela-and-more/

Three very recent films on the international scene, two of them exceptional and one of less artistic importance, are interconnected by both the sensitivity and the tenderness with which they have focused the love between two women. Their stories among the most beautiful provided by this thematic plot in the history of the screen. And to affirm it on a slope that has illuminated masterpieces like Carol and wonders like Disobedience is no small thing.

There are certain gay films with male characters who emulate rabbits in their animalistic urge to fornicate at all times, in any space, with anyone, through the vicissitudes of many bodily fluids and little love. On the other hand, these three stories of lesbian romance stand out in contrast, by celebrating the union of a couple with the understanding of an absolute physical and mental communion, one that dispenses with third parties. Then there’s the finding in the person loved the supreme enjoyment in the physical and spiritual, the acceptance of the other with all its burden of differences, their respect as a human being. This does not imply the overflow of eroticism and passion inherent in every bond that also possesses flesh and desire, manifested in the plots of these three filmic pieces bordered by intense sexual passages.

The first two are the Spanish Elisa and Marcela (Isabel Coixet, 2019) and the French Portrait of a Woman on Fire (Céline Sciamma, 2019); the other is the English The Secret of the Bees (Annabel Jankel, 2018). All of them have been directed by women and perhaps that is where the depth of the formation of the six central characters and their human richness lies; fundamentally the complicity in the approach to their sentimental and moral universes.

Co-written and directed by the Catalan Coixet, Elisa and Marcela, is based on true events that took place in primitive Spain, the first homosexual marriage in the history of that country. It occurred in 1901 by two Galician girls, albeit under the premise of a lie: one of them disguised herself as a man. Although it is still valid today, as they could never undo it, in the absence or flight of their spouses.

Teachers Elisa (Natalia de Molina, in another of the notable compositions of a career in ascent) and Marcela (Greta Fernández, the revelation actress of the moment in the Spanish Peninsula) fight at arm’s length to maintain their relationship in a patriarchal scene of ecclesiastical omnipotence. It is still far from being prepared in the psychological and cultural orders to metabolize such a bond. Misunderstood, rejected and ridiculed, the two young women must leave three countries on two continents in order to continue to be together.

The kernel of the story has to be peeled off in the lyricism by which Coixet approaches a love story. It’s shaped, seen and told from the presupposition of that incomparable beauty arising from loving and honoring being the object of veneration and desire. The intimate scenes of the two central characters are carefully beautiful, and they testify to their mime, to the carnality and spirituality of their passion, to the joint desire to please and love each other; in spite of the hatred and ignorance that hangs over both of them. De Molina and Fernandez, especially the first one, were great.

The visual splendor of black and white photography, great in several shots of interiors, enhances the film.

Portrait of a Woman on Fire, is sensory as the three previous works of its director, garments the model gradualness through which Sciamma works the romantic attraction of its protagonists. In the first hour of the film, which is calm in its progression and full of details, references and subtleties (those furtive or frontal glances of Héloïse, the lady to be painted, towards Marianne, the painter!

Portrait of a Woman on Fire, is sensory as the three previous works of its director, garments the model gradualness through which Sciamma works the romantic attraction of its protagonists. In the first hour of the film, which is calm in its progression and full of details, references and subtleties (those furtive or frontal glances of Héloïse, the lady to be painted, towards Marianne, the painter!

The two are also in conflict with each other. It was 1770 and the beautiful young bourgeois Héloïse had to be painted, in order to send the canvas to the rich Milanese man who was to marry her. Marianne represents, there is no other, given the time and the conventions, an episode that – although probably the most important thing in her life and never forgotten by her – has to be closed within itself once the lady travels to Italy with her husband.

Noémi Merlant (Marianne) and Adèle Haenel (Héloïse) compose two memorable characterizations. This is decisive in the sense of capturing their characters’ attempt to curb an instantaneous drive and the vehemence with which they accept it and give themselves over to the love affair after realizing how futile the commitment is. The stylization of Portrait of a Woman on Fire is largely due to the observation of the bodies and the close-ups. It’s pure filmic visual poetry that dialogues and transmutes with the pictorial space of the story. Thanks to the mailbox of Claire Mathom, the director of photography.

Despite being weighed down by dramatic and visually mellifluous decisions in the resolution, as well as appeals to misplaced magical realism and less nuance, The Secret of the Bees is also another tender female story. It is the 1950s in a rural Scotland that does not forgive the “lesbian” Dr. Jean (Anna Paquin, in a work of introversion unaccustomed to the actress in recent times), much less its clandestine union with the young worker Lydia (Holliday Grainger). The relationship between the two, despite their desire for anonymity, will be revealed in the air of a closed atmosphere of intolerance.

Despite being weighed down by dramatic and visually mellifluous decisions in the resolution, as well as appeals to misplaced magical realism and less nuance, The Secret of the Bees is also another tender female story. It is the 1950s in a rural Scotland that does not forgive the “lesbian” Dr. Jean (Anna Paquin, in a work of introversion unaccustomed to the actress in recent times), much less its clandestine union with the young worker Lydia (Holliday Grainger). The relationship between the two, despite their desire for anonymity, will be revealed in the air of a closed atmosphere of intolerance.

In director Jankel’s eyes, this love is marked by tenderness. Although the observation of the two women’s intimate space never reaches the degree of visual sophistication of the films of La Coixet and La Sciamma, such scenes are also very beautiful. Perhaps they are less stylized, but not all of them need to be assumed in such a way.

Agosto: A Different Film

Agosto: A Different Film

Agosto: A Different Film

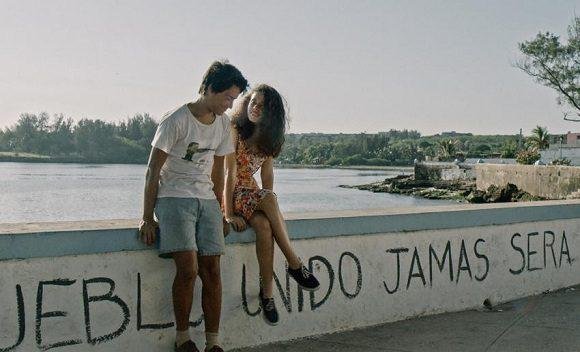

This is a film in every different sense that proposes a healing gaze towards that moment of farewells and separations.

December 11, 2019 12:12:07 | CLAUDIA PIS GUIROLA

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

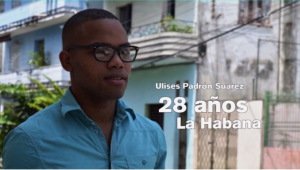

Photo: Frame of the film

It’s set in 1994 and Carlos is 14 years old. Some of his friends, neighbors and relatives leave Cuba behind the siren songs of the U.S. government. The US, which, while tightening the economic and financial blockade, promises benefits and guarantees to those who manage to set foot on American soil. In handmade boats, improvised from any material, they sail the seas: they are rafters. But Carlos (Damián González) is a teenager and in the midst of his personal pains, is unable to understand the full political-social dimension of the moment. Through his gaze, Agosto [August] is told. It is a film without excesses and with no desire to judge, which appeals to the collective memories of those who face the only Cuban film in competition in the section of Opera Prima during this 41st International Festival of New Latin American Cinema in Havana.

With the support of the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry (ICAIC), this production between Cuba, Costa Rica and France had to go through a long road of almost ten years to see materialize the original project of Armando Capó (director) with script by Abel Arcos. Finally, it is now possible to enjoy a work that, beyond the dramatic force of the context in which it is set, delves into more universal values such as adolescence, the loss of loved ones and the sexual awakening of a boy who will have to assume the socially accepted demands for his gender, but made even more acute by economic precariousness.

Capó, coordinator of the Fiction Chair at the International Film and TV School of San Antonio de los Baños, tells of a long documentary production (Descubriendo Pancha, 2004; La marea, 2009; Ausencia, 2011), which may have influenced the way the story is told. There are no dramatic effects or heartbreaking catharsis. Even the treatment of color from a palette without stridencies, the tempo of the edition and the use of hand-held camera contribute to achieving a story from a calm, with an unconventional narrative structure, but very attractive from, among other things, the careful recreation of the era.

With the performances of Glenda Delgado Domínguez, Felito Lahera, Verónica Lynn and Lola Amores Rodríguez, this is a film in a very different sense that proposes a healing gaze towards that moment of farewells and separations. That August was the same for many and those who still need a reconciliation with that summer, perhaps this August, will find it.

Gerardo and René on “Red Avispa”

Gerardo and René talk with Cubadebate about the film “Wasp Network” (+ Video)

By  Ana Álvarez Guerrero,

Ana Álvarez Guerrero,

Student of Journalism of the Faculty of Communication of the University of Havana. On Twitter: @aaguerrero97

and

Irene Pérez, Cubadebate photojournalist. Graduated in Journalism from the University of Havana (2014). Contact: irene@cubadebate.cu, on Twitter: @irenepperezz

Irene Pérez, Cubadebate photojournalist. Graduated in Journalism from the University of Havana (2014). Contact: irene@cubadebate.cu, on Twitter: @irenepperezz

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Heroes of the Republic, Gerardo Hernández and René González, share their impressions of the film “Wasp Network” [“Red Avispa”]. Photo: María del Carmen Ramón.

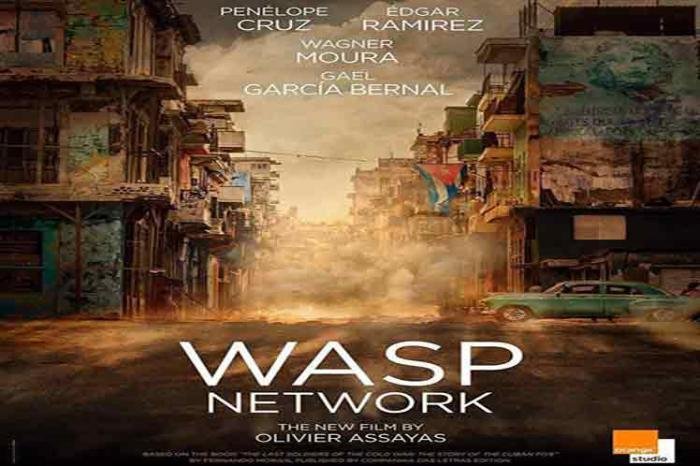

Heroes of the Republic of Cuba, Gerardo Hernandez and René Gonzalez, spoke today with Cubadebate about the Cuban premiere of the film “Red Avispa” at the 41st New Latin American Film Festival.

What did you both think of the film directed by French director Olivier Assayas?

The answer to this question and their impressions of this film – one of the most controversial of this edition of the Festival – were shared by Gerardo and René this afternoon, in an exchange that was transmitted through Cubadebate’s Facebook page.

Some of Gerardo and René’s impressions of the film

René:

The film, as many people have said, is not exactly the story of the Five, it is the story of part of the Five, but it also goes beyond that to the story of the confrontation between Cuba and the United States. It seems important to me that from the point of view of a European, who has no direct relationship with this conflict of so many years, a film has been made on a subject that, during the time in which this story unfolded, was a subject censored by the media of the world. That is the fundamental value of the film. I know that it will generate debate in the Cuban public, because it is the most difficult audience for a film like this. This is because it knows the case, it lived it. If the film gets a rating of 50 points from Cuban viewers, it’s a good film.

Gerardo:

What I liked most about the film was the boldness of placing the subject of terrorism in Hollywood. It is known that in Miami they have threatened to burn cinemas that show it. I think it’s brave to make a film that, without being pro-Cuban, embraces the truth and this truth favors us because we’ve been the victims for more than half a century.

René:

The film shows 50 years of aggression, terrorism, crimes against Cuba. They are not so afraid of the film as they are of the story, a story that if they could have told it they would have done it, they have money, connections. This was a trial in which the 12 members of the jury, when they left the courtroom, took an oath of silence, did not dare to speak. In another case, each one of those 12 members would have made his book of when he was a juror in the case of the 5.

This case filled the judicial system, the judge, the jury, the prosecutors with shame, that’s why it’s a story that they can’t tell and that they’re afraid of, and that for so long they hid and tried to let nobody know. They are afraid that the history of U.S. aggression against Cuba, for so many years, will be known.

Expect an expanded summary of Gerardo and René’s statements to Cubadebate.

The Wasp Network

SPECTATOR’S CHRONICLE

The Wasp Network

Finally screened at the 41st New Latin American Film Festival, The Wasp Network (Olivier Assayas, 2019) makes it clear with historical objectivity that the Cubans who infiltrated counterrevolutionary Miami exile organizations had the right to watch over their country’s security.

————————————————————————————————————-

Author: Rolando Pérez Betancourt | internet@granma.cu

December 8, 2019 22:12:47

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Finally exhibited at the 41st New Latin American Film Festival, The Wasp Network (Olivier Assayas, 2019) makes it clear with historical objectivity that the Cubans who infiltrated counterrevolutionary Miami exile organizations had the right to watch over the security of their country, and thus stop the wave of terrorist attacks of the 1990s carried out under the protection of the United States.

This is an important aspect to be taken into account in the film by the Frenchman Assayas, a prestigious director whose work is known in our country. He has made it possible to appreciate the sensitivity of an artist capable of tackling the most dissimilar human problems from intimate stories.

Based on the book The Last Soldiers of the Cold War, by Fernando Morais, Assayas himself wrote the script about a conflict that – it could not be otherwise – establishes who are the aggressors and who are the victims in a history that goes back half a century.

It was enough for the Miami counterrevolution, without seeing the film, only news after its presentation at the Venice Film Festival, to make a fuss and a pathetic warning: in those lands, the film couldn’t even show its head.

The theme of the Five Heroes and the stories that flow from it would allow us to make a few films and series. But in any work based on reality, there is a selection of events and characters, along with artistic licenses put into function of a dramaturgy and simplification of the plot. From Morais’s book, Assayas highlights what he considered pertinent to build a web of events that span several years and not a few intrigues. Although the film has been promoted as an espionage thriller, the director says that it is a historical vision conceived with the intention of capturing a feat that, after he learned about it it, captivated him.

It was advisable, however, to balance the tone and balance the conflict in such a way that a whole point of view in favor of the revolutionary cause did not prevail in a film with foreign funding and international distribution. Besides, the assumption of the political factor in any subject is always a reason for division of opinions and even entrenchments. These can be seen now, even, in “artistic” criticisms in which ideological positions against the “Cuban communist regime” stand out more than an unprejudiced practice of professional analysis.

But facts are facts and artistic honesty, although it is necessary to qualify, cannot be detached from them.

For this chronicler, The Wasp Network ends up being a film worthy and meritorious to see, which is not free of inconsistencies in its realization. Of these, the most significant, is the dispersion motivated by wanting to cover everything and explain more than necessary, taking into account the possible ignorance of the subject that an international audience could have. In this sense, the script resorts to leaps in time and an entry and exit of characters that leaves gaps in terms of purposes of the story and the lack of roundness of certain situations, such as the one concerning the flight to Cuba undertaken by the infiltrator Juan Pablo Roque (Wagner Moura).

Another debatable card -which for a Cuban spectator has nothing revealing about it- is the surprise factor that is intended to impregnate the infiltrators in Miami. It first, it makes them appear as traitors who escape from the Island and later, in their real function, a double game devoid of the dramatic force that, it is guessed, was among the director’s goals.

The Wasp Network is focused on the stories concerning René González (Édgar Ramírez) and his wife Olga Salanueva (Penélope Cruz, in an excellent performance).

Also the afore-mentioned Roque and the wife who is sought in Miami (Ana de Armas), each couple with their very particular love-political conflicts and was carried with considerable ease in the plot. Gael Garcia Bernal plays Gerardo Hernandez, leader of the group. It would be necessary to see the opinions that the real characters have regarding their characterizations.

The film efficiently reconstructs the terrorist attacks against tourist facilities, shows the maximum faces of the counterrevolutionary exiles and resorts to excerpts from the archives as a reminder that everything that counts comes from reality. This is how President Clinton and Fidel appear separately, towards the end, during an interview with an American journalist. Fidel is conclusive about the right of the most spied country in the world, Cuba, to know what the enemies are doing on U.S. soil to attack the Cuban people.

Hitler’s Hollywood

Hitler’s Hollywood

In the documentary a concept similar to Goebbels is clear: the masses don’t go to the movies to be taught, but to evade reality, hence the imperative to create artificial nirvanas for them. They didn’t even disguise their intention

—————————————————————————————————————

Author: Rolando Pérez Betancourt | internet@granma.cu

November 19, 2019 20:11:08

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Hitler reviewing a film, still from the documentary. Photo: Taken from the Internet

Although the Nazi cinematography gave a great deal of expression to its ideology, and did not spare any resources to do so, it also produced “escapist” stories – comedies, musicals, melodramas, police – aimed at distracting the attention of an audience trapped in a turbulent time.

Taken in numerical terms, it could be said that that duality in production was 50/50, according to the documentary Hitler’s Hollywood (2017), which forms part of a trilogy by the essayist Rüdiger Suchsland, aimed at examining the cinema of the Third Reich, close to a thousand films made between 1933-1945 under what was intended to be a “dream factory” in the best style of Nazi Germany.

Suchsland undertakes a methodical analysis -social, political and aesthetic- marked by objectivity and contention, without diatribes against films that would have deserved it for their racist and xenophobic approaches, a cinema that liked to proclaim that it would last a thousand years, and elaborated an ideological imaginary full of stereotypes against the ancestral values of humanity.

The exhibition of part of this work, which had its highest star in Hitler, has been forbidden in Germany and permissions are needed to project it as study material, therefore, it remains unpublished for the new generations, eager to know what was really that cinematographic gear marked by an insane policy.

Suchsland’s documentary brings us closer to the days when Nazi cinema put the greatest effort into the technical quality of its productions, trying to create its own “art” and compete with Hollywood, which it had no qualms about adapting, according to a scale of values that since the 1930s had been traced by the ideologists of Nazism (in that way, the artificial “American way of life”, distilled by American films, was finding its German equivalent in amelcochado films that glorified Nazi patriotism and sang praises to the times to come after the triumph of Nazism).

Although Hitler was known to like cinema, especially Disney’s work, the responsibility for driving the industry fell on Goebbels, with a culture fostered at universities in Bonn and Berlin. Appointed Minister of Propaganda and Information in 1933, one of his main tasks was to use schools and the media to turn Hitler into a god destined to dominate the world. And there is nothing better for it than cinema.

Rüdiger Suchsland, director and scriptwriter of the documentary. Photo: Taken from the Internet

Goebbels tried to have a Nazi Potemkim filmed for him. He also forbade a German version of Titanic from reaching the screens at the last minute in 1943, when the battle of Stalingrad turned the war upside down. The film could be interpreted as a metaphor for Germany sinking and overnight its director Helbert Sepin, who had left half a skin on the set, was [deemed] suspicious to the Gestapo and without trial or argument ended up on the gallows.

Willing to impress the world with his cinema, which, in terms of pace of production, came in second place behind Hollywood, Goebbel spared no money (or pressure) to ensure the permanence in the country of directors and stars. In the early days, he tried to overcome California’s Mecca internationally, forcing him not to touch on harsh subjects, not even to make horror films that could be “misinterpreted”.

Not a few of these films show the overflowing joy of the German people, a supposed enthusiasm embodied in comedies and musicals, and there is no lack of the technically brilliant (and repudiable in their content) documentaries by Leni Riefenstahl, an innovator with the camera who exalted the myth of the Aryan race to the point of exhaustion.

In Hitler’s Hollywood, a concept similar to Goebbels is clear: the masses do not go to the cinema to be taught, but to evade a reality, hence the imperative of creating artificial nirvanas for them. They didn’t even disguise their intentions and in this respect the narrator of the documentary says: “in general, Nazi cinema was thought to abolish all distinction between reality and fantasy”.

The truth is that by separating those films from marked ideological political propaganda, what remains is an entertainment cinema not very different from the one we see today. Director Rüdiger Suchsland says: “The entertainment industry has always had the function of controlling people. Even in democracies. It can be argued that, thanks to the internet and the almost total digitalisation of society, we are in a new stage of control and manipulation, and that the entertainment industry is less and less focused on developing free minds and illuminating them. That’s what I sometimes think, but I also believe that conspiracy theories and cultural pessimism are a serious danger to democracy. They’re there to make us feel powerless.

A thesis that links Nazi cinema to the present and that is not new. The essayist Siegfred Krakauer, in his great work From Caligari to Hitler (1947) revealed that the dominant psychological tendencies in that cinema “could be profitably extended to the study of the masses, both in the United States of America and in other countries”.

It is well known that when the Nazi empire disappeared, the American cinematographic expansion ended up taking over most of the world’s screens and today only one dream factory remains.

Agnes Varda’s Cuban Memory

Agnes Varda’s Cuban Memory

From April 29 to June 10, a hundred images of Agnes Varda can be seen by Cubans at the National Museum of Fine Arts in an exhibition that accompanies the 20th French Film Festival in Cuba. French Film Festival in Cuba

Author: Pedro de la Hoz | pedro@granma.cu

April 26, 2017 21:04:16

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

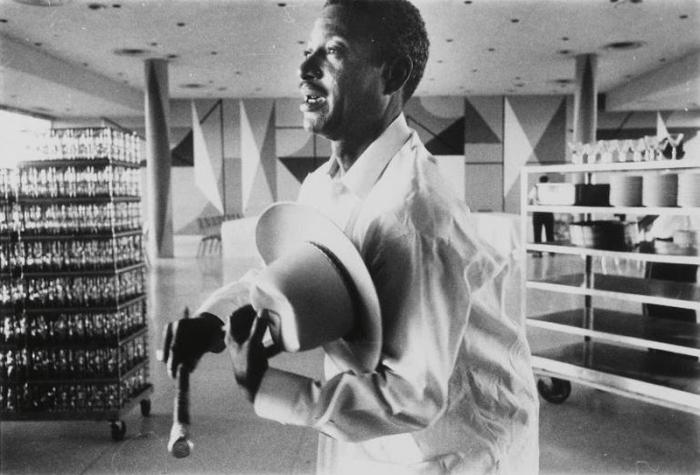

Benny Moré captured by Agnes Varda.

Agnes Varda arrived in Havana in the last weeks of 1962. She did not shrink from the recent events that had kept the world on edge, with the Island at the center of one of the most critical episodes of the Cold War, the missile crisis and the danger of nuclear war.

Shortly before, she married Jacques Demy, in his second marriage. He was two years away from becoming a famous filmmaker with the musical The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. She, of Belgian origin but French by adoption, had debuted on the big screen with the film La Pointe Courte in 1954, which dealt with the relationships of a couple in a fishing village from which she took the name of the work, and appeared as one of the most disturbing personalities of the so-called nouvelle vague (new wave) since the 1961 release of Cleo de 5 a 7, a sensitive reflection on the boundaries between life and death.

Since she traveled without a film crew, Varda chose to record reality with a small Leica camera and ordinary black-and-white film. She wanted to know what was happening in the streets of the city, among people she loved, laughed, danced, and did not stop to philosophize amid challenges and tensions arising from a revolution threatened by a powerful neighbor.

She was not an improvised photographer. In the early 1950s, after studying Art History, she worked as such for none other than the National Popular Theatre of Paris, directed by Jean Vilar.

But the idea of portraying Cubans did not mean for her to return to the field of photography, but to use the images in a film. In February 1963, she revealed her purpose in an interview published in La Gaceta de la Unión de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba: “I’ve been struck by how much people move and how they move, and I want to give you an idea about that. But I am going to express it with an opposite procedure: by means of fixed photos, which I will then animate based on the intermediate movements. Thus was born Saludos, cubanos (Salut les Cubains), which premiered in 1964.

In the winter of 2015, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris asked the mythical filmmaker – at that time she was revered for La felicidad (1965), Daguerrotipos (1975), Sin techo ni ley (1985, winner of the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival) and Jacquot de Nantes (1991) and had just become the first woman to be awarded the Palme d’Honneur in Cannes – to collect the Havana photos for the first time.

She thought that the curatorship would opt for other images, for example, according to her words “a portrait of Salvador Dalí, another of Eugene Ionesco or things from the Europe of the 50s and 60s, considering that Cuban photographs were never conceived to be exhibited”.

Varda/Cuba was a rediscovery. There were Fidel Castro, smiling despite the fact that when the photographer found him she asked him not to smile; those who had learned to read from the 1961 national literacy campaign who later decided to train as teachers, cane cutter volunteers, teenage loves, and children’s games.

That’s where the great Benny Moré appeared, with his unbeatable singer’s stamp even when he knew he had been wounded to death, and a very young Sara Gómez, dancing a cha cha chá dressed as a militia member for the days when she dreamed of being the first Cuban filmmaker.

From Saturday, April 29 to June 10, Cubans can see a hundred of Varda’s images. The National Museum of Fine Arts will display them in an exhibition that accompanies the 20th French Film Festival in Cuba.

Some will succumb to nostalgia. Others will not, because they will see in that graphic testimony, more than an unrepeatable moment, the trace of what was carved in time, of a resistant spirit.

http://www.granma.cu/cultura/2017-04-26/memoria-cubana-de-agnes-varda-26-04-2017-21-04-16

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Published on Jan 28, 2016

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Agnes Varda’s Benny More video.

A Comedy in a State of Grace

La Viña de los Lumiere

Hunt for the Wilderpeople from New Zealand: A Comedy in a State of Grace

By Julio Martinez Molina

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann

British comedian Ricky Gervais says that “comedy is that moment when the mind tickles itself”. My mind which at this point –after so much limp and conventional boring comedy– has forgotten about tickling was however exulted and rolled with laughter when I saw a model of the genre like New Zealand’s Hunt for the Wilderpeople. I’ve owed this post to that film since I saw it two years ago; and since then I have not seen any other movie of my once beloved genre with so much comic efficacy.

The film fulfills, and surpasses the cardinal objective of the genre recognized by Chaplin himself: to entertain and make people laugh. His formula, not new, operates perfectly here: a plot whose dramaturgical thread and whose cause-and-effect sense have organic purpose in the structure of situations –logically overlapped and sustained—are conducive to hilariousness. The timing and duration of the gags are perfect. Most dialogues, the precise and semi-invisible emotive handling of the characters/actors function without failure. This is all a result of the good work in the characterization and direction of the actors and the empathy arising from their interaction. The recipe never failed: from [Ernst] Lubitsch and [Billy] Wilder to the first Farrelly.

However, in truth, this film by director Taika Waititi, bears little relation to that kind of cinema in other aspects. The geographical context and the tone used represent the adaptation of the best concepts of those masters to the peculiar expressive coordinates and appetites of the comedy. These confer a very rare injection of weirdness to the essence of a genre that is blown up from within by means of the most gentle dynamite cartridge in the universe. It unleashes a strong implosion of endorphins coated with affection, tenderness and the resulting joie de vivre. But, beware, this is nothing like a “feel good movie”, or the commonplace “funny” story. With this film we thank life, without restrictions or double intentions. It does not feel the need to say anything fashionable for others to applaud. Perhaps, it is in the deep and timeless simplicity of its statements that lies part of its charm.

Hunt for the Wilderpeople makes you roll [on the floor] with delightful laughter from beginning to end. It finds in its main character –teenager Ricky Baker (Julian Dennison)– its best hilarious asset. This chubby, rebel, gang-hip-hop lover, who must march, wander, and run for his life, through the intricate forests of the New Zealand archipelago, is perfectly drawn as a character. The actor who plays the role –I can’t think of any other like him to do it– depicts him with colors full of endearing and overflowing sympathy.

When the spectator does not want a comedy to end, it has done its duty. With Hunt for the Wilderpeople one feels this desire, which is currently in a state of extinction after the poor state of the genre. Good comedies are nowadays isolated exceptions that usually come from emerging cinema industries (like this one), but which are unfortunately made invisible (like this one too) by the world film distribution apparatus.

+++++++++++++++++++++

*Julio Martinez Molina: Film Critic, member of the Cuban Association of the Cinematographic Press and of the UNEAC. Author of the books published on film criticism: “North America and the Cinema of the End of the Century”, Sources and Influences of Contemporary Cinema” and “Haikus of My Filmic Emotion.

Last Tango in Paris: Truth or Lie?

SPECTATOR’S CHRONICLE

Last Tango in Paris: Truth or Lie?

Last Tango in Paris (Bertolucci, 1972) has been shown again these days at the Yara cinema as part of a series entitled Placeres y Angustias de la Carne (Pleasures and Anguishes of the Flesh), and with it comes “the latest” -which is really not so new-, related to one of the most controversial films in the history of cinema.

Author: Rolando Pérez Betancourt | internet@granma.cu

September 2, 2018 18:09:42

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

LAST TANGO IN PARIS (Bertolucci, 1972) has been shown again these days in the Yara cinema as part of a series entitled Placeres y angustias de la carne (Pleasures and Anguishes of the Flesh), and with it “the latest” comes to light -which is not really so new-, related to one of the most controversial films in the history of cinema. “The Last” refers to some statements made by Bernardo Bertolucci for the French Cinémathèque in 2013 and aired on YouTube in 2016 on the occasion of the International Day Against Gender Violence.

There, the Italian director was putting the stamp on what had long been vox pópuli in the film world: the rape scene (using butter) had not been agreed-upon with the actress Maria Schneider. Rather, it was a trap devised the day before by Marlon Brando, and accepted by him [Bertolucci] to obtain a true veracity.

It should be remembered that Last Tango … narrates the passionate, and not infrequently violent, relationship of a 19-year-old girl with a 48-year-old man and, according to its director, he wanted Schneider not to interpret her humiliation and rage, “but that she really felt it ».

The statement again put on the table the old controversy of how far art can get to capture what the creator proposes. In a short time the video had more than half a million views, not a few condemning Bertolucci and Brando.

Actresses like Jessica Chastain and Chris Evans declared that they would never see the film again, nor would they look at its director and main actor in the same way.

LAST TANGO IN PARIS ran the risk of returning to go to the bonfire, as happened at its premiere, although in those days from the perspectives of a prudish morality that banned it in several countries, including Italy, cradle of its director.

Then came the urgent statement from Bertolucci saying that the assembly of his statements had been misinterpreted on YouTube and that the scene of the rape, which was not real, was in the script. The only new thing was “to use the butter” and take her by surprise “so that she would react like a girl, not like an actress,” he reiterated.

Maria had already died of cancer, in 2011, at age 58.

In 2007 she had made statements to the Daily Mail that did not reach light until 2016, along with the new controversy: “during the scene,” she said, “even if what Marlon did was not real, I really cried. I felt humiliated and, to be honest, a little violated by Marlon and Bertolucci. At least it was only one take ».

She would not tire of repeating that she had ended up hating them both and having finished her career she entered a psychiatric clinic. Depression would mark her for life and it is not risky to say that in it much had to do the film that brought her to know fame.

Some said unjustly in those days that she had been far below Brando, without taking into account that Maria’s inexperience, being nude for part of the plot, and forced to respond to the constant improvisations of her partner, as Bertolucci allowed to the actor to change and contribute whatever he wanted in full shooting.

Impressed by the performance of the young woman, many first-line directors -Buñuel, among them- went out to hunt her, but she simply did not measure up.

Today LAST TANGO IN PARIS is the great film that is, regardless of the comments-truths, half-truths and lies-that will continue to arrive, even if not one member of the audience from the time of its release, who applauded and were moved by her, remains alive.

Lizette Vila’s documentary

Paquito el de Cuba

Lizette Vila’s documentary or Padres en plural

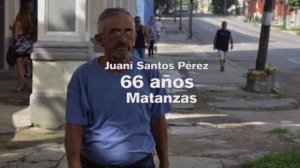

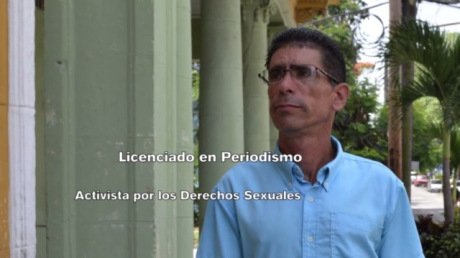

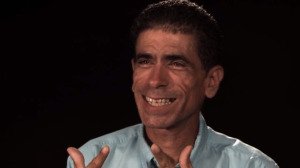

By Francisco Rodriguez Cruz

November 19, 2017.

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

I’m not going to try to do a review or evaluation of Lizette Vila and Ingrid León’s documentary, because I’d be a judge and a party, and that would be very ugly. Even more so when I’m still under the impression of the apotheosis of the premiere that Soy papá had this Saturday, November 18th… anyway, in a Yara cinema at full capacity, which forced me to offer a double performance.

I just wanted to thank you for the gift, which was great, for my son, my partner and me, that we were able to enjoy it also among so many good and friendly people. I barely recover, though, from the shock of seeing my face – what a horror! – on the big screen.

I just wanted to thank you for the gift, which was great, for my son, my partner and me, that we were able to enjoy it also among so many good and friendly people. I barely recover, though, from the shock of seeing my face – what a horror! – on the big screen.

I also self-critically admit that I underestimated the impact of this bringing to life of the Palomas Project.

A little more than 30 minutes with the biographical shreds of a dozen or so men, I never thought they would attract so much kind and even overwhelming attention from a wide and diverse audience.

Personally, what I liked the most was to know the other stories of this choral interview – moving at times, sometimes hilarious, always authentic, by what they show, and even more, by what one can guess behind each testimony.

It was nice, but undeserved to be able to share the stage with such great parents at the end of the screening, and to receive with them, their families and my son Javier, the solidarity and affection that the audience lavished on us with an applause that I interpret as a recognition, not individual, but collective, for all the parents.

It was nice, but undeserved to be able to share the stage with such great parents at the end of the screening, and to receive with them, their families and my son Javier, the solidarity and affection that the audience lavished on us with an applause that I interpret as a recognition, not individual, but collective, for all the parents.

Because beyond the explicit purposes that link it with international campaigns and just social causes, this audiovisual is ultimately a claim to paternity, the best balance of which is not melodrama -which there is, there was no lack of it, we speak of Lizette Vila – but the natural force of a joy, accomplishment or pride that is difficult to explain, but easy to perceive even in her saddest or most heartbreaking stories.

Because, beyond the explicit purposes that link it with international campaigns and just social causes, this audiovisual is ultimately a claim to paternity. The best balance of this is not melodrama -which there is, there was no lack of it, we speak of Lizette Vila – but the natural force of a joy, accomplishment or pride that is difficult to explain, but easy to perceive even in her saddest or most heartbreaking stories.lk;

Omar Montalvo Chirino

Another great success was its projection on the eve of November 19, 2017, International Men’s Day, a celebration that has existed since the 1990s, but we rarely remember it.

This makes it all the more valuable and timely to look at these Cuban parents – parents or biographers – who share different experiences from different ages, marital status, professions, territories;

without forgetting variables such as sexual orientation and gender identity, as they include other male perspectives that the traditional notion of manhood usually tries to ignore, silence or at least diminish, disguise.

Another great success was its projection on the eve of 19 November 2017, International Men’s Day, a celebration that has existed since the 1990s, but we rarely remember it.

I am therefore pleased to be part of this thoughtful, disturbing and problematic tribute to the most intense and enriching human experience I know: being a father.Juan Nodarse Ramos

Thank you, Ingrid; thank you, Lizette.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

You must be logged in to post a comment.