Uncategorized 7

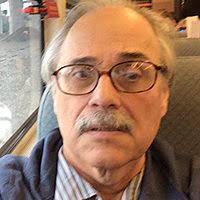

Leo Frumkin, 1928-2022

Leo Frumkin, 1928-2022

by Sherry Frumkin and Jim Lafferty

Photo by Edmon J. Rodman

A memorial will be announced at a later date.

Received by email

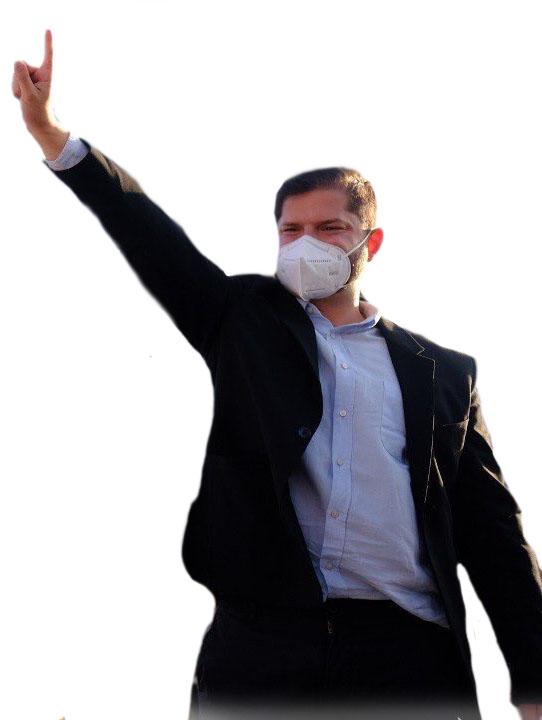

AMLO May 8, 2022 speech in Cuba

Andrés Manuel López Obrador: “I have never bet, nor will I bet on the failure of the Cuban Revolution”

By Andrés Manuel López Obrador

May 8, 2022

Translated by Pedro Gellert F.

Miguel Díaz Canel Bermúdez, president of Cuba, awards the José Martí Order to his counterpart of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Photo: Abel Padrón Padilla/ Cubadebate.

SPEECH BY MEXICAN PRESIDENT ANDRÉS MANUEL LÓPEZ OBRADOR DURING HIS VISIT TO CUBA

Friends, before reading the text I wrote for this important occasion, I would like to convey my condolences to the families of the victims of the calamity that occurred in a hotel under repair here in Havana. I extend to you a heartfelt embrace.

I would also like to send greetings and our affection to all the mothers of Cuba, those who are here on the island and those who are abroad.

President and friend Miguel Diaz Canel

All my friends,

Without wanting to exalt the chauvinism that almost all Latin Americans carry within us, it is safe to say that Cuba was, for almost four centuries, the capital of the Americas.

No one coming from Europe to our hemisphere could fail to pass through the largest island of the Antilles, and for many decades Cuba was the jewel of the Spanish Crown.

For a very long time, Cuba and Mexico, due to their geographic proximity, migratory flows, language, music, sports, culture, idiosyncrasy, and sugarcane cultivation, have maintained relations based on true brotherhood.

It is even possible that in pre-Hispanic times, there were Mayan inhabitants from the Yucatan peninsula on the island, who in addition to possessing a splendid culture, were like the Phoenicians, great navigators who maintained trade relations not only with the peoples of the Gulf of Mexico, but with those of the Caribbean as far as Darien.

But leaving this very interesting subject to anthropologists and archaeologists, what is certain is that the first expeditions departed from Cuba toward what is today Mexico and it was from Cuba that Hernán Cortés’ soldiers sailed their ships to undertake the conquest of Mexico. It is also known that even with the differences that this intrepid and ambitious soldier had with Governor Diego de Velázquez, all the assistance to take on the indigenous resistance in Mexico departed from Cuba by orders of the Spanish monarchy.

During the colonial period, in Cuba, as in Mexico, there were epidemics and the super-exploitation of the native population, which was practically exterminated. This explains the outrageous and painful boom of the African slave trade in Cuba and the Caribbean in general as of the 16th century. Once I had the opportunity to visit the old city of Trinidad and went to the Museum of Slavery and saw whips, shackles, and stockades of whose existence I was aware due to the comments written concerning the punishments meted out by the peonage laws that were in force in Mexico several decades after our political independence from Spain.

You should know that in our country, slavery was not actually abolished until 1914. Moreover, it should be noted that just three years earlier, in 1911, the great peasant leader Emiliano Zapata took up arms because the sugar estates were invading the lands of the villages of the state of Morelos with impunity.

However, sugar cane, royal palm, and migration from Cuba to Mexico is most noticeable in the Papaloapan Basin in the state of Veracruz. Havana is like the port of Veracruz, and it is the inhabitants of Veracruz who are the most similar to Cubans. By the way, my father’s side of my family was from there.

Our peoples are united, as in few cases, by political history. At the beginning of Mexico’s Independence, when there were still constant military uprisings and battles between federalists and centralists and liberals against conservatives, there were two governors of Cuban origin in my state, in Tabasco, Infantry Colonel Francisco de Sentmanat and General Pedro de Ampudia.

Coincidentally, the confrontation of these military leaders would serve, in these times, for writing an exciting, tremendous, and realistic historical novel, whose brief story is that one of these leaders defeats his fellow countryman and governor militarily and he goes abroad and recruits a group of Spanish, French, and English mercenaries in New York and organizes an expedition to invade Tabasco. However, when the foreigners disembarked, they were defeated and put to the sword, while ex-governor Sentmanat’s head was cut off, and on the recommendation of a doctor or physician, it was placed in a pot of boiling water to delay its decomposition due to the heat and for it to be able to be exhibited as punishment for a few days in the public square. This inhuman procedure was not unknown in Mexico nor uncommon in other parts of the world. The Father of our Homeland, Miguel Hidalgo, who proclaimed the abolition of slavery, when he was apprehended by orders of local and Spanish oligarchs, was not only shot, but also decapitated, and his head was put on display for ten years in the main square of Guanajuato. Militarism is barbaric and belligerent conservatism breeds hatred and savagery.

But history is not lineal nor Manichean; it does not consist of good and bad individuals, but of circumstances. General De Ampudia ordered Sentmanat’s execution, because according to his words, a “terrible and exemplary punishment” was needed, then he played an exemplary role in 1846, as defender of the city of Monterrey, during the U.S. invasion of Mexico; and later, in 1860, he served as Minister of War and Navy in the liberal government of Benito Juarez.

The list of Cubans who fought on behalf of Mexico during the U.S. and French invasions is extensive and broad. Likewise, there were Mexicans who fought here for the liberation of Cuba. In the times of Juarez, Mexico was the first nation in the Americas to support the independence of Cuba and to recognize Carlos Manuel de Cespedes, the president in arms and father of the Cuban homeland.

And what can we say about the great services rendered to our country by the Cuban Pedro Santacilia, son-in-law of President Juarez and his main confidant. Juarez, during his exile, was here and in New Orleans, where he met the person who would later marry his daughter Manuela.

Juarez’s confidence in his son-in-law was so great that during the most difficult moments of the French Invasion, it was Santacilia who took care of the family of the defender of our Republic in the United States. Juarez called him “my Saint”. No one received as many letters from Juarez as Santacilia. No one shared the moments of greatest sadness and happiness of the “Distinguished Patriot of the Americas” as he did.

In the midst of so many gestures of brotherly ties, it is unthinkable that José Martí would not have been so closely linked to our country. The Cuban writer and political leader lived in Mexico City from 1875 to 1877. There he wrote essays, poetry and, among many other works, the famous theater script “Love is repaid with love”. He was a columnist for the newspaper El Federalista, linked to the liberal president Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, and when the latter was overthrown by a military movement led by Porfirio Díaz, Martí left Mexico and with the vision that only the great possess, he wrote to his friend Manuel Mercado that he was leaving, and I quote, because “a man declared himself by his own volition lord of men…. and with a little light in your mind one cannot live where tyrants rule”.

Even though Porfirio Díaz’s seizure of power sparked Martí’s anger, it should also be taken into account that by then he had already set his sights on participating in the struggle for Cuban independence.

In addition to always maintaining an epistolary relationship with his friends in Mexico and returning to our country for the last time in 1894, there is a parallel story to Martí, the Cuban independence fighter, in the figure of the Mexican revolutionary Catarino Erasmo Garza Rodríguez. Despite being little known in history, in the same timeframe Garza had the audacity to lead a guerrilla movement from Texas and call on the people of Mexico to take up arms to overthrow Porfirio Díaz, 18 years before Francisco I. Madero did in 1910.

Catarino Garza was from Matamoros, Tamaulipas and lived in Laredo and other towns along the U.S.-Mexico border. On September 12, 1891, he crossed the Rio Grande River heading up a squadron of 40 combatants and on the 15th of that month he issued the Cry of Independence in Camargo, Tamaulipas. In one of his proclamations to stir the people against Porfirio Diaz, Garza denounced, before others did, the grave injustice of the dispossession of the lands of the indigenous communities, declared by the regime as wasteland to benefit large national and foreign landowners. Catarino was a journalist and his manifestos were constant, profound, and well written. However, in the military field he achieved little with his movement; he barely gathered together about 100 combatants and of his four incursions into Mexican territory he only won one victory at Rancho de las Tortillas, near the village of Guerrero, Tamaulipas. But even without winning many battles, the challenge of this fighter sparked deep uneasiness in the Mexican military elite who, in collaboration with the U.S. Army and the famous Texas Rangers, mobilized thousands of soldiers to practically seal off the border and carry out a tenacious search village by village, ranch by ranch, in pursuit of the rebel chief, his small band of troops, and his sympathizers.

In these circumstances, Catarino disappeared and amid conjecture, the legend and the inseparable corrido ballad arose, which in one verse proclaimed:

Where did Catarino go

with his pronounced plans

with his insurgent struggle

for the Mexican American.

The mystery was cleared up when, sometime later, it was discovered that Garza had appeared in Matina, a town on the Atlantic coast of Costa Rica. Before that, he had been hiding here in Havana, protected by his pro-independence Masonic brothers.

In those times, Costa Rica was the meeting point and the ideal terrain to prepare guerrilla forces and landings of the most important revolutionaries of Latin America and the Caribbean.

The president of Costa Rica, Rafael Iglesias Castro, was a tolerant liberal and respectful of the right of asylum. Hence, in the Costa Rican capital, leaders and military leaders prepared the struggle for the independence of Cuba, the integration of the Central American countries, and the reconstitution of greater Colombia, projects sealed by word of honor, in which there was also the commitment to support Catarino in overthrowing Mexico’s dictator.

In this atmosphere of brotherhood, Catarino established close relations with Cubans, Colombians, and Central Americans. In Costa Rica there were around 500 Cuban refugees, the most prominent of whom was Antonio Maceo, the general who, together with Máximo Gómez, fought for the Independence of Cuba and was considered a threat by the Spanish colonial government.

The presence of Maceo did not go unnoticed in Costa Rica. Rubén Darío, the great Nicaraguan poet, recalls that one day he saw “coming out of a hotel, accompanied by a very white woman with a fine Spanish body, a large and elegant [man]. It was Antonio Maceo. His manner was cultured, his intelligence lively and vivacious. He was a man of ebony”.

Maceo was indispensable for the victory of the Cuban liberation movement. The duo he formed with Máximo Gómez was the main concern of the Spanish monarchy. That Spain would lose its last important bastion in the hemisphere depended on them. Hence the impetuous phrase, and I quote: “(Winning) the Cuban War is only a matter of two happy bullets […] to be used against Maceo and Gomez”.

But, just as his enemies sought to eliminate Maceo, the Bronze Titan, there were others who considered him indispensable. This was the opinion of José Martí, the most intelligent and self-sacrificing figure in the struggle for Cuban Independence. Despite the differences, Martí demonstrated a patriotic humility in his relationship with Generals Máximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo.

This explains why Martí went to Costa Rica twice to see Maceo. Later, in November 1894, after the attempt in Costa Rica on the life of Maceo, with his unique prose, Martí wrote an article from New York in which he said:

“Let the Spanish government use as many assassins as it pleases. General Maceo and his comrades will in due time, in any case, be given the position of honor and sacrifice that the homeland bestows on them. Assassins can do nothing against the defenders of freedom. The infamous stab that wounds the revolution, that wounds the hero comes from those who criminally seek to extinguish the aspiration of a people”. Strictly speaking, to wound Maceo was to wound the heart of Cuba.

Although Catarino knew Maceo, he finally chose to link up with the radical Colombian general Avelino Rosas and his confidant, journalist and writer Francisco Pereira Castro. At that time, among other Colombians, the famous General Rafael Uribe Uribe, also a friend of Maceo’s, was conspiring in Costa Rica. He inspired Gabriel García Márquez to create the character of Colonel Aureliano Buendía in his famous novel One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Facing all kinds of adversities, betrayals, and hardships, as usually occurs in these struggles, Rosas was able to define and undertake a revolutionary plan to rescue Colombia from the conservatives. Thus, he ordered Catarino to take action to seize the barracks and the port of Bocas del Toro, now in Panama.

Catarino’s anticipated expedition began in early February 1895 almost at the same time as Maceo’s voyage to Cuba.

We owe the best information about Catarino’s incursion and its tragic end to Donaldo Velasco, the commander of the ports of Bocas del Toro and Colon, who, the year after the events in question, that is, in 1896, published a booklet in which in good prose he narrated everything that occurred. Thanks to this cultured conservative, we know the details of the final odyssey of the revolutionary Catarino Erasmo Garza.

The mission was not an easy one, but the idealism of the revolutionaries is an extraordinary source of inspiration and represents a very powerful force.

Once the landing was made in Boca del Toro, after four o’clock in the morning of March 8, 1895, the guerrilla chiefs positioned the 30 combatants to simultaneously attack the police and military barracks. Velasco recognized that “they had managed to surprise us when we least expected it, in spite of so many warnings…”.

The fighting was intense and there was hand-to-hand combat:

In the first new minutes, several soldiers fell. Catarino led the action with passion and courage. However, “two almost simultaneous shots… mortally wounded him: … his agony was brief”.

Shortly afterward, at 5:00 a.m., the bugle of the soldiers sounded powerfully, playing a reveille as a sign of victory.

In the report on the battle sent to General Gaytán, who was in David, Panama, it was reported that five guerrilla fighters and nine soldiers had died, with eight wounded; “in the latter category, some, on both sides, died later”.

At 4 o’clock in the afternoon, Catarino Erasmo Garza Rodriguez, Francisco Pereira, and two other comrades were buried in a deep grave in the pantheon of Bocas del Toro, located on the seashore. “Where a man falls, he remains”, Che Guevara would say seven decades later. We are currently conducting an investigation to recover the remains of Catarino Garza and take them to Mexico.

The information of what occurred in Bocas del Toro made its way to all the islands and ports of the Atlantic Coast.

Porfirio Diaz found out about all this on March 11, through a cable sent by his ambassador in Washington, Matias Romero.

On whether Catarino was a revolutionary or, as it was said at that time, a bandit, besides the opinion each person might have, there is a verdict in of considerable value since it was sustained by a loyal and proud conservative, the Colombian Donaldo Velasco. In his text, this important protagonist and witness of the final events could not hide his deep admiration for Catarino, and I quote: “…He was not, in my opinion, the vulgar bandit portrayed by the Americans […]. Even after his death, he inspired respect…”.

This story could not end without clarifying that, even after seizing the Bocas del Toro barracks, Catarino went on to defeat an even more powerful enemy. At dawn, at the entrance of the bay, the Atlanta, an imposing U.S, warship, awaited him with its cannons; a steel hull of 96 meters in length and 284 U.S. Navy sailors. All this firepower, to pursue and annihilate, pardon the paradox, Catarino “the pirate”. Those were the times when the North Americans had decided to become the owners of the hemisphere and defined what they considered their vital physical space in order to then undertake the conquest of the world. Annexations, independence, the creation of new countries, free associated states, protectorates, military bases, landings, and invasions to put in and remove rulers at will were at their peak.

We do not know if it was due to the commander’s false statements or by decision of the supreme command in Washington -as the crew of the Atlanta had no need to intervene-, the U.S. Navy certified that it had made, and I quote: “a landing in Bocas del Toro, Colombia, on March 8, 1895, to protect American lives and property threatened by a Liberal Party revolt and pirate activity”. The Marines were even decorated.

In a brief account and in homage to men of revolutionary ideals, the same year that Catarino and Pereira fell, Martí died; Maceo was assassinated in 1896; Rosas, in 1901. Such has also been the fate of many forgotten but sacred anonymous heroes and of others who will continue to emerge, because the struggle for the peoples’ dignity and freedom is a never-ending story.

Even though my text is already very long -that’s right, isn’t it, Beatriz?- I apologize. But in discussing our close relationship, Mr. President, I cannot fail to mention the outstanding and dignified role of Manuel Márquez Sterling, Cuban ambassador in Mexico during the coup d’état, imprisonment, and assassination of President Francisco I. Madero and Vice President José María Pino Suárez.

In those times of vultures, when the U.S. ambassador organized the coup against our Apostle of Democracy, Francisco I. Madero, the Cuban ambassador, in stark contrast, tried to save his life, offered asylum to prisoners and spent a night with them in the quartermaster of the National Palace, where they were held for five days before the terrible crime of killing them in a rampage occurred.

Márquez Sterling relates in his book that my fellow countryman, Vice-President José María Pino Suárez, during that solidarity visit, prophetically confessed to him the following: “our imposed resignation provokes the revolution; murdering us is equivalent to decreeing anarchy. I do not believe, like Señor Madero, that the people will overthrow the traitors to rescue their legitimate leader. What the people will not consent to is that they shoot us. They lack the civic education necessary for the former. They have plenty of courage and strength for the latter…”.

And so it was, on February 22, 1913, at midnight, the president and vice-president legally and legitimately elected by the people of Mexico were cowardly assassinated. From that moment on, José María Pino Suárez’s prediction began to be fulfilled; as soon as they were killed, the Revolution furiously erupted. On March 26, 1913, Venustiano Carranza, governor of Coahuila, signed along with other revolutionaries the Plan of Guadalupe to restore legality and depose the coup general Victoriano Huerta, who had appointed himself president.

Huerta remained in power for a year and a half. Carrancistas, Zapatistas, and Villistas independently of each other fought him, and achieved the fall of the usurper, who, at that time, was unable to obtain the support of the U.S. government.

During the whole period of the Revolution, exiles lived in Cuba, both Porfiristas and Huertistas as well as Maderista revolutionaries. It is said that in the streets of Havana, here, they insulted each other. For example, the revolutionary from Veracruz, Heriberto Jara, one of the inspirers of the oil expropriation carried out in 1938 by General Lázaro Cárdenas del Río, lived here.

Nor can I fail to mention the supportive role of the Mexican people and governments in relation to the Cuban revolutionaries who fought against the Batista dictatorship.

As we know, and as you recalled, my friend President Miguel Diaz-Canel, when you visited us last year on the occasion of the commemoration of the 200th anniversary of Mexico’s Independence, the passage of Fidel and his comrades through Mexico left a deep impression on the future expeditionaries of the ‘Granma’ and a host of legends everywhere, which are still spoken of with admiration and respect.

We will never forget [you said] that thanks to the support of many Mexican friends, the Granma yacht set sail from Tuxpan, Veracruz, on November 25, 1956. Seven days later, on December 2, the newborn Rebel Army, which came to free Cuba, disembarked from that historic vessel.

You went on to say:

Nor do we forget that only a few months after the historic victory of the Revolution in 1959, General Lazaro Cardenas visited us. His willingness to stand by our people following the mercenary invasion of Playa Girón in 1961, marked the character of our relations.

President Diaz Canel also explained that:

Faithful to its best traditions, Mexico was the only country in Latin America that did not break relations with revolutionary Cuba when we were expelled from the OAS by imperial mandate.

As for my convictions about Commander Fidel Castro and Cuban independence, I reiterate what I wrote recently in a book:

Over a long period, as oppositionists in Mexico, Fidel was the only one of the leftist leaders who knew what we stood for and distinguished us with his support in reflections, in writings, and in political deeds of solidarity. We never met, but I always considered him a great man because of his pro-independence ideals. We can be for or against him as a person and his leadership, but knowing the long history of invasions and colonial rule that Cuba experienced in the framework of the U.S. policy of Manifest Destiny and under the slogan “America for the Americans”, we can appreciate the feat represented by the persistence, less than a hundred kilometers from the superpower, of the existence of an independent island inhabited by a simple and humble, but cheerful, creative and, above all, worthy, very worthy people.

That is why, when I was visiting Colima and learned of the death of Commander Castro, I declared something I felt and still hold: I said that a giant had died.

My position on the U.S. government’s blockade of Cuba is also well known. I have said quite frankly that it looks bad for the U.S. government to use the blockade to hinder the well-being of the Cuban people so that they, the people of Cuba, will be forced by necessity, to confront their own government. If this perverse strategy were to succeed -something that does not seem likely due to the dignity of the Cuban people to which I have referred-, it would in any case turn this great offense into a pyrrhic, vile and despicable victory, into one of those stains that cannot be erased even with all the water in the oceans.

But I also maintain that it is time for brotherhood and not confrontation. As José Martí pointed out, the clash can be avoided, and I quote: “with the exquisite political tact that comes from the majesty of disinterest and the sovereignty of love”. It is time for a new coexistence among all the countries of the Americas, because the model imposed more than two centuries ago is exhausted, has no future or end strategy and no longer benefits anyone. We must put aside the dilemma of integrating with the United States or opposing it defensively.

It is time to express and explore another option: that of dialogue with U.S. leaders and convince and persuade them that a new relationship between the countries of the Americas, of all the Americas, is possible.

Our proposal may seem utopian and even naïve, but instead of closing ourselves off, we must open ourselves to committed and frank dialogue, and seek unity throughout the Western hemisphere.

Furthermore, I see no other alternative given the exponential growth of the economy in other regions of the world and the productive decadence of the entire Americas. Here I will repeat what I have expressed to President Biden on more than one occasion. If the economic and trade trend of the last three decades continues -and there is nothing that legally or legitimately can prevent it-, in another thirty years, by 2051, China would have a 64.8 percent share of the world market and the United States only between 4 and up to 10 percent. This, I insist, would be an economic and commercial imbalance that would be unacceptable for Washington and that would keep alive the temptation to wager on resolving this disparity with the use of force, which would be a danger for the whole world.

I am aware that this is a complex issue that requires a new political and economic vision. The proposal is, nothing more and nothing less than to launch something similar to the European Union, but in accordance with our history, our reality, and our identities. In this spirit, the replacement of the OAS by a truly autonomous organization, not a lackey of anyone but a mediator at the request and acceptance of the parties in conflict in matters of human rights and democracy, should not be ruled out. Although what is proposed here may seem like a dream, it should be considered that without the horizon of ideals you get nowhere and that, consequently, it’s worth trying. It is a great task for good diplomats and political leaders such as those that, fortunately, exist in all the countries of our hemisphere.

For our part, we believe that integration, with respect for sovereignty and forms of government and the proper application of a treaty for economic and commercial development, is in the interest of us all and that no one loses in this. On the contrary, it would be the most effective and responsible solution given the strong competition that exists, which will increase over time and which, if we do nothing to unite, strengthen ourselves, and emerge victorious in good terms, will inevitably lead to the decline of all the Americas.

Cuban friends,

Dear President Díaz Canel,

I conclude, now, with two brief reflections:

With all due respect for the sovereignty and independence of Cuba, I would like to state that I will continue to insist that the United States lift the blockade of this sister nation as a first step to initiating the reestablishment of relations of cooperation and friendship between the peoples of the two countries.

Therefore, I will insist in discussions with President Biden that no country of the Americas be excluded from next month’s Summit to be held in Los Angeles, California, and that the authorities of each nation freely decide whether or not to attend this gathering, but that no one be excluded.

Finally, thank you very much for the distinction of awarding me the Order of José Martí, whom I respect and admire, as I admire and respect Simón Bolívar and our great President Benito Juárez.

Thanks to the generous, supportive, and exemplary people of Cuba.

On a personal note, I maintain that I have never wagered, nor do I wager nor will I wager, on the failure of the Cuban Revolution, its legacy of justice and its lessons of independence and dignity. I will never participate with coup plotters who conspire against the ideals of equality and universal brother and sisterhood. Stepping backward is decadence and desolation, it is a question of power and not of humanity, I prefer to continue maintaining the hope that the revolution will experience a rebirth within the revolution, that the revolution will be cable of renewal, to follow the example of the martyrs who fought for freedom, equality, justice, sovereignty. And I have the conviction, the faith, that in Cuba they are doing things with that purpose in mind. That the new revolution is being made within the revolution. This is the second great message, the second great lesson of Cuba for the world, that this people will once again demonstrate that reason is more powerful than force.

Thank you very much.

Plaza de la Revolución, Havana, Cuba, May 8, 2022

Source: https://presidente.gob.mx/discurso-del-presidente-andres-manuel-lopez-obrador-en-su-visita-a-cuba/

The ‘American way’ of imperialism

On this Memorial Day, 2022, I thought that this draft of an article that I wrote six years ago for the Encylopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism was an appropriate answer to those who celebrate all wars and distinguish among their victims.

—Norman Markowitz, May 30, 2022

US imperialism, social costs

The ‘American way’ of imperialism

By Norman Markowitz

The terms ‘imperialism’ and ‘colonialism’ are often used interchangeably but they are not the same. Formal colonies based on direct control of territories are the best-known form associated with imperialism, a form which covered large parts of the world until its collapse after the Second World War. Two forms of indirect control, the establishment of what now are usually called ‘client states’ (formerly called ‘protectorates’ or ‘satellites’) and spheres of influence, together often called ‘neo-colonialism’ in Africa and other former colonial regions, are the leading expressions of imperialism today. This indirect control functions through bilateral and multilateral military alliances, and bilateral and multilateral trade agreements on the model of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The American anti-colonial revolution of the 18th century established a republic which began to call itself a democracy in the 1830s before any other modern nation did. Thomas Jefferson, revolutionary leader and author of the Declaration of Independence, advocated an ‘empire for liberty’, a continental empire which through territorial expansion would enable farmers and artisans to live in peaceful and prosperous coexistence with the merchant capitalists, slaveholders, and large landowners – the ruling elites of the new republic. Jefferson as president advanced this policy through the early 19th century

US expansion through the 19th century was to contiguous territories. Indigenous people, called ‘Indians’, were the first direct victims of this ‘empire for liberty’. They signed treaties which US governments routinely broke, and were forced onto reservations after many bloody wars by the end of the 19th century.

lt would not be until the early 1930s that the first serious reforms in US government policy toward indigenous peoples would be enacted under the leadership of John Collyer, director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, in the New Deal Government of Franklin Roosevelt.

The indigenous peoples were defined as ‘savages’, whether they were land-owning and even slave-owning Cherokees in Georgia, warring Apaches in the South West, Sioux horseman in the Dakotas, or buffalo herders on the plains. And ‘savages’ had no rights to land because they could not develop the land.

The most important long-term social cost of this policy to the American people perhaps was the connection of these policies with concepts of ‘democracy’; a ‘democracy’ based on exclusion of ‘Indians’, slaves, Spanish-speaking Mexicans seen as inferior to Anglo-Saxons, a policy which by the 1840s was called ‘manifest destiny’

Manifest destiny was often associated with anti-colonial rhetoric. The conquest of much of northern Mexico in the Mexican-American war (1845–49) was, for example, seen by some as a war to destroy the last vestige of the Spanish Empire in North America . The slave states were among the strongest supporters of manifest destiny and abolitionists opposed the Mexican War as a slaveholders’ conspiracy to expand slavery, seeking unsuccessfully to have Congress block war appropriations and also pass the abolitionist-inspired Wilmot Proviso, a congressional resolution which would have barred slavery on all territories taken as a result of the war.

Manifest destiny in the hands of pro-slavery politicians led the slave states to attempt to expand their system into the western territories through the brutal fugitive slave act (1850), the failed ‘Ostend Manifesto’ calling for the purchase of Cuba, Spain’s major slave colony (1854), the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854), repeal of the Missouri Compromise of 1819 which restricted slavery geographically, and the subsequent use of force to impose a pro-slavery constitution in the Kansas territory. The slave states also demanded total compliance with the slaveholder-dominated Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision (1857), which would have declared slavery to be legal everywhere in North America and deprived all free Blacks of citizenship rights.

US imperialism in the age of industrial/financial capitalism

In the last decades of the 19th century, the major European powers began to extend colonial imperialism and fight with each other for colonies, protectorates, and spheres of influence around the globe. This was the imperialism of industrial/financial capital, an imperialism which sought markets and raw materials like the earlier commercial capitalist imperialism, but now began to export capital itself to find cheaper and cheaper labour for an expanding world market which needed in quantity and variety more raw materials, larger markets, and much greater military and naval forces to defeat imperialist competitors and subjugate people.

By the 1880s, the US began to strengthen its naval power (a policy endorsed by the steel Industry) as its industrial capacity grew by leaps and bounds. US investors bought sugar and other plantations in Spanish Cuba and the Independent Kingdom of Hawaii, and competed for commercial gain and influence against European imperial powers and the Japanese Empire in China and the Pacific.

In Hawaii, American planters, faced with economic ruin thanks to the McKinley tariff of 1890, colluded with US officials to launch a ‘revolution’ in the islands and annex them to the US. This policy was implemented paradoxically by President McKinley (1897), whose tariff (in the interest of the stateside industrialists who generally supported the Republican Party) threatened the American planters in Hawaii, who were also strong supporters of the Republican Party. For the indigenous population of Hawaii, territorial status meant, as Jawarlal Nehru would say famously about British imperialism in India, living as servants in their own homes. As Britain sent indentured Indian labour to its African colonies, the US would, through negotiations with Japan and China, import Japanese and Chinese labour to the Hawaiian Islands.

Spanish-American War and the ‘Cuban model’ of US imperialism

Faced with an uprising in Cuba against Spanish colonial control which threatened US investments, the McKinley Administration declared war on Spain in 1898, ostensibly to liberate Cuba. Very soon, the US navy destroyed the Spanish Pacific Fleet and occupied the Spanish colonial Philippines in the Western Pacific. When the smoke had cleared, the McKinley Administration, in the face of substantial opposition, annexed the Philippines and Guam in the Pacific and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean as colonies.

While this was ‘minor’ compared to British, French, German, and Belgian colonisation in Africa, and British and French colonisation in Asia, it was the first overseas colonial intervention by US military forces. The US in the first years of the 20th century fought a bloody counter-insurgent war against Filipinos who had initially welcomed them as liberators, losing many more troops then they had in the Spanish-American war itself, destroying whole villages, and taking the lives of an estimated 250,000 Filipinos.

In Cuba, the US first refused to permit the Cuban revolutionary army to participate in the surrender of the Spanish colonial forces in 1898, and then refused to end its occupation of the island until the Cubans had written into their constitution the Platt Amendment, a resolution drafted by Senator Orville Platt of Connecticut. The amendment demanded Cuban acceptance of the US government’s right to determine Cuba’s economic relations with foreign powers and intervene militarily in Cuban affairs to ‘protect Cuban self-determination’. To back this up, Cuba also ceded a naval base at Guantanamo Bay to the US.

The ‘Cuban model’, accurately called by American anti-imperialists ‘gunboat diplomacy’, was rapidly extended to many nations in Central America and the Caribbean, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and beyond. Just as Britain had played the leading role in the development of the Suez Canal and then used defence of the canal to extend its empire, President Theodore Roosevelt bought out the assets of a bankrupt French company seeking to build a canal through the Columbian province of Panama and then conspired with the CEO of the company to stage a ‘revolution’ supported by the US navy to establish an ‘independent Panama’ which would permit the US to build the canal. The existence of the canal and its defence then became a rationale for scores of US interventions mostly carried out by the Marines, whose actions were romanticised in US popular media in ways similar to those of British Grenadiers and other colonial forces elsewhere.

The direct relationship of US corporations and investors with the US government was deepened and US military and civilian authorities both exported racism across the Caribbean, Central America, and the Pacific and through those actions intensified racism at home. Two examples highlight this. At a time when European colonialists were contending that colonies would serve as a way to export socially disruptive surplus populations from the imperialist countries, Senator John T. Morgan of Alabama, leader of the Democratic minority on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, wrote to the State Department suggesting the possibility of resettling Southern Blacks in the Philippines and giving them land that would be taken from the Filipinos (the State Department didn’t reply). African-Americans, fighting in the segregated units of the US army against the Filipino uprising, faced for the first time appeals from Filipinos not to fight for whites who oppressed them against a dark-skinned people. Also, there were reports that both white and black US soldiers, in burning Filipino villages, would shout ‘Nigger’, long established as the most pre-eminent hate word in the US, at the Filipinos. From their letters back home to family, friends, and ministers, it is clear that many African-American troops were particularly traumatised by the open and extensive racism of a war in which they were fighting in the army of the racists.

Under the Platt Amendment, there would be major and minor US military interventions until Franklin Roosevelt formally repudiated it, rejecting US direct military intervention to protect US economic interests and proclaiming a hemispheric ‘Good Neighbor policy’.

Here are a few highlights nation by nation of that policy, called gunboat and dollar diplomacy in the US and ‘Yankee imperialism’ by most Latin Americans. The US applied Platt Amendment principles to turn the Dominican Republic into a protectorate (1905) and Marines occupied the Dominican Republic (1916–24) to maintain order and protect US investments. When US-trained National Guard leader Rafael Trujillo became dictator of the Dominican Republic in the mid-1930s without direct US intervention, Franklin Roosevelt said famously ‘he’s a son of a bitch but he is our son of bitch’, a frank admission of what the US policy of gunboat/dollar diplomacy meant, even after the gunboats were withdrawn

The administration of President William Howard Taft further developed this policy, encouraging US investment banks to invest in China and Caribbean nations to strengthen US interests against imperialist rivals The US also enlarged its naval military power to protect these growing investments. Under Taft, this was known as ‘dollar diplomacy’. Under what should be called gunboat/dollar diplomacy, Marines occupied Nicaragua in support of President Diaz, former treasurer of a US mining company (1910), and then reoccupied the country to crush anti-Diaz forces as he held an election with 4,000 eligible voters and himself as the only candidate The US kept troops in Nicaragua until 1925. The following year, Marines returned to battle the radical reformer Augusto Sandino, whom the Coolidge Administration called an agent of a ‘Nicaraguan-Mexican-Soviet’ conspiracy to establish ‘Mexican-Bolshevist hegemony’ over Nicaragua as a springboard to attack the Panama Canal (1926), a Monty Pythonesque early expression of what was later known as the Domino Theory.

US Marines left Nicaragua in line with the Good Neighbor Policy (1933) but National Guard Commander Anastasio Somoza murdered Sandino and established a family dictatorship which lasted from 1934–78. While FDR expressed no sympathy for Somoza, he somewhat disingenuously contended that intervention against him would be a return to the Platt Amendment in violation of the Good Neighbor Policy.

Interventions might also be ‘private’. The overthrow of a liberal regime in Honduras was funded by banana company tycoon, Sam Zemurray, and directed by US mercenary Lee Christmas, whom new conservative president Manuel Bonilla made head of the Honduran army (1911). The Harding Administration brokered a deal with Guatemalan elites to oust a liberal government for the United Fruit Company (1921).

Racism, always present, sometimes took strange turns. Under Woodrow Wilson, who rejected ‘dollar diplomacy’ verbally but increased US military interventions in the Caribbean, the US occupied and turned Haiti into a protectorate (1915). US troops remained until 1934. During the First World War, Franklin Roosevelt, assistant secretary of the Navy, actually wrote the Haitian Constitution. In 1919, the US Marines ruthlessly suppressed a Haitian uprising, During the occupation, Haitian presidents and other prominent Haitians were barred from the elite US Officers Club on the island because they were black!

Gunboat/dollar diplomacy continued unabated in Cuba. A Cuban uprising against the Platt Amendment led to an invasion/occupation by Marines (1906–09). US Marines intervened again under Taft to smash a strike of sugar workers which threatened US, investors (1912). US Marines re occupied Cuba (1917–22) under Wilson and Harding until ‘stability’ (protection of US economic interests) was restored. These policies created enmity toward ‘Yankees’ and ‘Gringos’ throughout Latin America.

But the Marines were often glorified in US media under such slogans as ‘the Marines have landed’ and ‘the Marines are here to clean house’. Such headlines were similar to media portrayals of British Grenadiers and French Foreign Legionnaires in the British and French Empires, creating mutual hostilities that undermined positive relationships.

The New Deal Government inherited these policies in the midst of a global depression. As in other areas, Roosevelt, a major reformer in the US context but no revolutionary, sought to reshape this policy in ways that would win over the people of Latin America without abandoning US business interests. First, Roosevelt announced a Good Neighbor Policy and abrogated the Platt Amendment (1933–34). He surprised many by sending US warships to support democratic forces which in 1933 ousted the brutal Cuban tyrant Gerardo Machado (toasted by Coolidge and Wall Street in the 1920s). This was a rarity in history, where the US intervened against a right-wing dictator.

But then, faced with a reformist government and a powerful left, the US supported strongman Fulgencio Batista behind the scenes in establishing his first dictatorship to protect US investments on the island. Mexico was a much greater problem which FDR responded to in a creative way, making his fullest break with gunboat/dollar diplomacy and advancing a policy of Pan-American co-operation.

Under Woodrow Wilson, the US launched a naval assault and occupation of Vera Cruz, Mexico, in opposition to military strongman Valeriano Huerta, whom Taft had supported in the overthrow and murder of the reformer Francisco Madero as the Mexican Revolution ended the 40-year dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz (1914). Wilson’s subsequent interventions, first for and then against North Mexican leader Pancho Villa, led Villa to launch raids against US territory as the First World War raged in Europe. Wilson sent the US army into Mexico to catch him. This ended disastrously, as US troops clashed with anti-Villa Mexican forces and never caught their target. In the aftermath of the Coolidge intervention in Nicaragua (defined as a defence against the expansion of ‘Mexican Bolshevism’ which would threaten the Panama Canal but in part a ploy against Mexico’s threat to nationalise US oil holdings), the Hoover Administration sent warships to support the defeat of an uprising in El Salvador of workers and peasants led by communist Faribundo Marti, the first real communist-led revolutionary uprising in the Western hemisphere, resulting in the killing of Marti and the massacre of over 8,000 peasants and workers (1932).

When Mexican President Lazaro Cardenas nationalised the Mexican oil industry and US investors, led by the Hearst Press demanded military intervention of the kind that Coolidge had used against Nicaragua, Roosevelt responded by having the Import Export Bank give Mexico a $25 million loan to compensate US investors. US–Mexican relations sharply improved under the Roosevelt Administration even though Cardenas was by far the most socialist-oriented president that Mexico would have in its history.

As a complement to its Good Neighbor Policy, the administration fostered a broader vision of Pan-Americanism based on co-operative hemispheric economic development. However, these policies would not survive the beginnings of the Cold War. An attempt was made by left New Dealers in the Board of Economic Warfare (BEW), chaired by vice president Henry Wallace, to extend the New Deal through Latin America. They sought to have firms with US government contracts provide their workers with minimum wages, trade union rights and other benefits the New Deal had established for American workers, but the initiative was defeated by conservative elements within the administration backed strongly by Wall Street.

Under the Truman Administration, the US Army established the School of the Americas (1946) an upgrading and major extension of the Hoover policy of training and making into middlemen the Latin American military elites whose principal role would be to fight their own people. The school remains in existence today, having trained thousands of future military and police authorities including officers who would lead in the overthrow of democratically elected governments and advance policies that would lead to the deaths of tens of thousands of their own people.

Globalisation of gunboat/dollar diplomacy

When the Second World War ended, US prestige among progressive and revolutionary forces through the world was never greater. Under the New Deal Government of Franklin Roosevelt, the US had served as the centre of the ‘Allied Powers’, holding the British Empire, under conservative leadership seeking to maintain its empire, and the Soviet Union, under Communist leadership fighting a war of survival and liberation for its own people and the people of Europe together, to defeat the fascist imperialist Axis powers.

The US had also used its influence to establish a United Nations organisation, and under the New Deal Government (itself relying on a domestic centre-left coalition of labour and political forces) advanced policies to make the UN serve through its social agencies as the force to implement global policies to increase food production, sanitation and health care, international labour standards that address the economic and social inequalities that produced war and past imperialist policies which had greatly increased all of those inequalities.

But the balance of political forces in the US had changed significantly during the war. Wartime economic expansion connected to the creation of what would later be called the military-industrial complex strengthened corporate and conservative forces. They would recycle and update US policies of gunboat/dollar diplomacy and seek to apply these to the whole world.

The big picture of US imperialism and the Cold War

First, the Truman Administration expressed hostility to the Soviet Union from its very first days in April 1945, as the Red Army fought the last Battle of Berlin and the European War ended. Then the Truman Administration, initially fearful of the Red Army’s military power and the influence of the Soviets and Communists throughout Europe and Asia, began to see in the atomic bomb a weapon that could enable it to frighten the Soviets into complying with its demands for the economic and political organisation of post-war Europe and Asia.

Even before the Second World War ended, the Truman Administration had adopted the policy that Churchill in the last years of the war sought to have FDR adopt: to abandon anti-fascist co-operation with the Soviets and ‘Big Three Unity’ and move toward a policy of undermining communist-led insurgent movements, even if that meant quietly embracing fascist collaborator forces, as the British army did in the fall of 1944 when they invaded Nazi-occupied Greece and opened fire on the communist-led insurgents who had led the fight against the Nazis since the German invasion.

The US also began this policy in the Asia Pacific region even before the end of the war. In the bloody fighting for control of the Philippines, General MacArthur’s Intelligence staff put down its most important grass-roots ally, the communist-led people’s army (HUKs) which had saved the lives of Americans and worked with American troops, as the British had in Greece months before. After the Japanese surrender, the Truman Administration used the large Japanese armies on the Chinese mainland as a police force to keep, as Truman admitted in his memoirs, the Chinese Communist Party, whose influence had grown tremendously during the war, from leading the Chinese people to victory.

Also, the Truman Administration retained the Japanese emperor, Hirohito, whom Americans during the war had seen along with Hitler and Mussolini as the third member of an ‘Axis of Evil’, and gave him and all members of an extended royal family immunity from war crimes prosecution, even though a number were directly involved in atrocities against the peoples of China and other Asian nations.

When the war ended, Korea was ‘temporarily divided’ into US and Soviet zones of occupation. In the South, Syngman Rhee, a conservative who had spent most of the previous 35years on US soil, was brought in by the US occupation. Rhee was soon to become ‘our son of a bitch’, the first of many local tyrants whom the US would establish and/or keep in power. In Korea, the US occupation employed well-known Japanese collaborators in the police to suppress student and worker opposition to Rhee and the American Military Government (AMG).

US policy was deeply influenced by its closest ally the British Empire, mixing and matching old British imperialist policies of creating balances of power, now in the name of ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’ as against the British ‘progress’ and ‘civilisation’. After the British army attacked the anti-Nazi resistance movement in Greece in 1944 (a centre of its ‘traditional sphere of influence in the eastern Mediterranean) and installed a conservative monarchist regime filled with many Nazi collaborators and pre-war Greek fascists, a bloody civil war ensued. But by the winter of 1947, the British Empire, bankrupt ideologically and financially, was withdrawing everywhere.

The Truman Administration, already using threats against the Soviets in Europe and recruiting former Nazis from the Intelligence and police services of Axis Europe, ‘experts’ in anti-Communism and anti-Sovietism, leaped in with a ‘Greek Turkish Aid bill’ to replace Britain in the Greek Civil War. Along with this specific policy, Truman called for a US commitment to ‘aid free peoples’ who are fighting against ‘subjugation’ by ‘armed minorities’ or ‘outside pressure.’

Former vice president Henry Wallace called this ‘Truman Doctrine’ a ‘world Monroe Doctrine’. One could also call it an extension of gunboat/dollar diplomacy imperialism from the Caribbean and the Western Hemisphere to the whole world, with a new version of the Platt Amendment giving the US the ‘right’ to intervene in the affairs of all nations in defence of their rights to ‘self-determination’ and ‘independence’ as the US government defined these terms.

In the years to come the earlier invasions of Cuba, Nicaragua, the Dominican Republic, the failed interventions in Mexico, would be repeated in Greece, Korea, Vietnam, Taiwan, Lebanon, Iraq, directly; and in France, Italy, Indonesia, the Congo, Brazil, Chile Angola, Mozambique, East Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq, and today Syria, indirectly. These direct and indirect interventions were in support of ‘our sons of bitches’ around the world with military and economic ‘aid’; the training of military and police forces; the advance of ‘free-market’ policies that aided foreign investors and local elites; and the fomenting of economic crises and internal subversion against those governments which resisted these policies. The process was ritualistically defended as a major part of an unending war against a Soviet-directed ‘world Communist conspiracy’, a perpetual Cold War to prevent a nuclear hot war.

The big picture of Cold War and ‘post-Cold War’: consequences for the US

The distinguished historian of US foreign policy Walter LaFeber estimated that US military spending during the period from the Truman Doctrine to the dismemberment of the Soviet Union, with all of its hidden and ancillary costs, amounted to 10 trillion dollars. By a conservative estimate, given military spending over the last 22 two years in the ‘post-Cold war period’, spending has been even greater than that. The pattern of expansion (Korean War), plateau (post-Korean War), expansion (Vietnam War) very short inflation limited plateau (post Vietnam War) great expansion (Reagan Hollywood ‘virtual wars’), plateau (‘post-Cold war’), G.W. Bush expansion, called by historian James Reed ‘Reagan on steroids’ (‘wars and occupations against terrorism’ Afghanistan, Syria, Ukraine, and who knows where next) continues to this day, regardless of the administration.

The pre-Cold War policy of US imperialism (the use of protectorates, satellites, client states and spheres of influence as against formal colonies) had both avoided the high overhead costs of the former Great Powers’ colonial imperialism and the politically disadvantageous loss of life that their colonial military interventions had led to. This was its ‘strength’ as it developed its control over the Western Hemisphere and campaigned to open up the colonial regions, protectorates, and spheres of influence of its imperialist rivals.

The’ globalisation’ of this policy with the Truman Doctrine, the formation of NATO and subsequent multilateral military alliances (SEAT0, CENT0) and numerous bilateral military alliances, meant that from 1947 to the present the US would spend much more on the global Cold War and its sequel, the global war against terrorism, than all of its allies and enemies combined. Also, the US would in the name of ‘containment,’ ‘counter-insurgency,’ ‘low-intensity wars’ and ‘proxy wars’ do among the great powers most of the fighting and suffer most of the casualties in the large Cold-War Korean and Vietnam Wars and later ‘wars against international terrorism’ in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Some speculation about the costs of roads not taken

In calculating the ‘price’ of American imperialism to the American people, the overwhelming majority of whom are workers and salaried employees, retirees (former workers and salaried employees)m students (future workers and salaried employees), many of the costs are incalculable, because of what did not occur. How much higher would general social security benefits have been over the last 66 years if general revenues had been added to the regressive payroll taxes (which Roosevelt showed sympathy for and progressives put forward in legislation), if the social-security-based national health system that was the subject of a fierce legislative battle after the war had been enacted, if the large public power projects on the TVA model for the Columbia and Missouri Rivers had been enacted, along with public housing legislation on the model of the original United States Housing Authority and federal aid to education in the model of the National Youth Administration.

Given the wartime economic expansion, the establishment during the war of a system of progressive taxation, the fact that one-third all workers outside of agriculture were unionised and (even with the divisions between the conservative exclusionist AFL and the inclusionist CIO), the organisational support to establish this post-war programme, to which public opinion was sympathetic, existed on paper in 1945.

The Cold War was not the only reason why groups like the American Medical Association, the National Association of Manufacturers, the US Chamber of Commerce, and the private power companies were able to bury this programme, but it was a central reason.

The association of this programme (a social-security-based system of national health care, public power expansion on the TVA model, federal aid to education, housing, and transportation,) with ‘creeping socialism,’ the purges in the trade union movement and the arts, sciences and professions of its most militant advocates, all in the name of Cold War anti-Communism, systematically doomed the programme. And there were other costs that could not easily be calculated in dollars and cents.

For example: the cost to the trade union movement over the last 66 years of tens of millions of real and potential members as the number of workers in private-sector unions dropped from 35 per cent in 1947 to single digits today; the cost to hundreds to millions of Americans over that period of many billions of dollars in out-of-pocket health-care expenses that working people in the rest of the developed world do not have to pay; the high rate of infant mortality relative to other developed countries that exists in the US; and the emergence from the Reagan era to today of children as the largest group living in poverty.

Interventions and their concrete social costs

Here are some of the most important Cold-War interventions and their social costs.

In China, the Truman Administration spent over $3 billion in military aid to Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang regime (1945–49), organised the regime’s ‘elite divisions’, and only ended its formal aid when the revolutionary forces had clearly gained the upper hand. The US then refused to recognise the Peoples Republic of China, blocked its admission to the UN until 1972, and did not establish full diplomatic relations with it until 1978, providing over time many billions of dollars in military aid to ‘the Republic of China’ (Chiang’s rump regime in Taiwan). Also, the US helped to train Chiang’s commandos for raids of the Chinese mainland, threatened war with China in the 1950s over the islands of Quemoy and Matsu in the Formosa Strait, provided financial and indirect military aid to feudal-religious elements for an uprising in Tibet against the People’s Republic of China (1959), and subsequently, as it came to recognise China, manoeuvred to create conflicts between China and India and use China as a ‘strategic ally’ against the Soviet Union.

For the American people, the costs were real-war dangers as US paratroops prepared to attack the Chinese mainland in the event of full-scale war in the Formosa Strait in the mid-1950s, a peacetime draft that undermined working-class communities by taking from those who could not be deferred for medical reasons or were enrolled in colleges or were unacceptable due to criminal records.

In Italy, the new CIA ‘passed’ its first ‘test‘. The agency (called by its members ‘the company’) spent millions of dollars to defeat a united front of Communist and Socialist Parties which had been expected to win the 1948 elections. It also used the Democratic Party to mobilise Italian Americans to send telegrams to relatives, provided both Marshall Plan aid and other forms of aid to the Italian government, funded Mafia elements in Sicily and southern Italy to undermine a free election, and continued over the next four decades with limited success to try to defeat and isolate the Italian Communist Party, supporting both former and neo-fascists, traditional conservatives, and anti-communist factions of the Socialist Party to achieve those ends.

The CIA’s activities began a pattern of involvement with organised crime groups who would use their increased wealth and connections to develop in the 1950s the heroin market in US working-class communities, destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and increasing crime significantly in US cities.

After independence in the Philippines (1946), which the New Deal Government had promised in the 1930s, US ‘military advisors’ organised the campaign to crush the communist-led anti-Japanese Huk army, electing and then removing Filipino presidents until the 1960s when one of their ‘assets’, Ferdinand Marcos, realising that the US was turning against him, made himself ‘president for life’.

US agribusiness corporations, Dole especially, participated in and profited greatly from the exploitation of the Filipino people in alliance with terroristic regimes and local right-wing gangs to murder peasant organisers and drive poor peasants from their land.

Edward Landsdale, a classic imperialist adventurer in the tradition of Britain’s Chinese Gordon and Lawrence of Arabia, organised the post-war political campaign to elect Ramon Magsaysay as president of the Philippines, then led the US military mission to French colonial Indochina (1953) to remove the French and bring in Ngo Dinh Diem, a US ‘asset’ to establish a dictatorship, and finally served as director of the CIA’s Operation Mongoose (1961), the largest and most expensive CIA operation in the world aimed at overthrowing the revolutionary government of Cuba and murdering Fidel Castro and its other leaders.

Lansdale, an advertising man from San Francisco before the Second World War, was the stuff of which 19th-century imperialist ’heroes’ were made. He even used his influence to have Hollywood change the screenplay of Graham Greene’s novel The Quiet American, turning a character widely believed to be based on him from a villain to a hero.

The US intervention first in the French colonial war and then in its own version of a colonial war (1950-–75) would eventually cost directly 58,000 lives, hundreds of thousands wounded, and the psychic trauma that many experienced because of the atrocities that were and are the reality of ‘counter-insurgency’ as against the rhetoric of winning the hearts and minds of the people. Of course, it also cost the people of Indochina over 3 million lives. For millions of Americans, the great struggles unleashed by the Civil Rights movement and enacted in Great Society legislation brought with them the possibility of winning decisive victories against poverty and racism in the US. The intervention in Vietnam, when all the slogans were stripped away, was, like the dozens of interventions in Latin America before and during the Cold War, a war against the poor with a large racist subtext.

US involvement in the Korean civil war (1950–53) was explained to Americans as a UN ‘police action’ (US interventions in the Caribbean had been defined as the use of ‘the international police power’ under the Platt Amendment to ‘maintain order’ and protect ‘independence’). The Korean War produced a ‘truce,’ a devastated Korea (an estimated 3 million dead) with the US creating the largest ‘protectorate/satellite’ in its history, establishing a large military presence and forward bases against North Korea, China, and potentially the Soviet Union, supporting repressive regimes and the military over the decades, and doing nothing to resolve either the Korean national question or the threat of war that its large and costly military presence represented and continues to represent.

Full globalisation of the Truman Doctrine after Korea meant spending trillions of dollars over time on military-industrial complex corporate subsidies, a ‘warfare state’ that would prevent the development of a modern ‘welfare state’ social system in the US.

Over subsequent decades, US life expectancy declined in relation to other developed countries, public education and child-care services both stagnated, and the US developed a much higher level of income and wealth inequality.

And a phenomenon the CIA called ‘blowback’, that is, disastrous unintended consequences, became a result of US policy.

The US intervened indirectly in Iran (1946) against a Soviet-supported uprising by the Azerbaijani minority in northern Iran (Azerbaijan was a Soviet republic at the time) threatening the Soviets indirectly with nuclear blackmail, but then had to withdraw their support. The Iranian government followed with widespread repression against the Azerbaijani minority.

After Mohammed Mossadegh, democratically elected prime minister, nationalised what was a private monopoly of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, Britain launched a blockade of Iranian oil. When the US government refused him any assistance, Mossadegh turned to the Soviet Union to break the blockade. The Eisenhower Administration then declared Mossadegh a ‘communist‘ and orchestrated his overthrow (1953), replacing him with the Shah, previously a constitutional monarch, who established a brutal terroristic dictatorship in which the US was the principal backer and beneficiary. The oil was then privatised and, in a classic imperialist ‘re-division,’ US oil companies received 40 per cent, other US-influenced companies 20 per cent, and the former Anglo-Iranian oil company, now calling itself British Petroleum (BP), more famous today in the US for spilling oil than spilling blood, received the remaining 40 per cent.

US corporations did very profitable business with and in Iran for the next 25 years, selling arms, engaging in construction projects, and taking their cut of the oil. Secular liberal forces, the Tudeh (Communist) Party, and all other opponents of the regime were ruthlessly suppressed, leaving the Islamic clergy as the only major venue for opposition.

The 1979 revolution, in which millions took to the streets, millions who understood the history of 1953 and all that had followed, was taken over by a section of the Islamic clergy to establish a clerical ‘Islamic Republic’ which channelled mass opposition to imperialism into portrayals of the US and its people as ‘the great Satan’ and secular ‘Western society’ as at war with all Muslims. US corporations lost billions in Iran, although the US froze Iranian assets in US securities valued at over $20 billion in 1980. (They remain frozen, and their present value is unknown.) The Reagan Administration did ‘receive’ over $50 million dollars from the Iranian government in the illegal ‘arms for hostages’ deal in order to provide the Iranian military, which had received arms from the US until the revolution, with weapons to use in their war against Iraq, which the Reagan Administration had supported.

Most of this money ‘disappeared’, although some was siphoned off to support the Nicaraguan Contras, an expression in the 1980s of old-fashioned Platt Amendment gunboat diplomacy.

Among the most important social costs of the ‘warfare state’ in the US was a labour movement whose leadership supported all of these policies and did nothing to resist the massive export of capital abroad, which was in effect the domestic policy of imperialism in the US, producing chronic economic crisis and a political vacuum on the labour left which, with the blowback of the Iran Hostage crisis, provided the background to the Reagan presidency.

Gunboat/dollar diplomacy also returned with a vengeance to Central America when the CIA overthrew the democratically elected Arbenz Government in Guatemala (1954) and brought to power a brutal dictatorship under Carlos Castillo Armas (a US-trained officer) which would take thousands of lives: the most terroristic regime in the region to date

When the Cuban revolution triumphed in 1959, the National Security Council and the CIA were initially confident that Cuba would be another Guatemala After a steady escalation of attacks on the revolutionary government and an embargo which compelled it to turn to the Soviet Union for aid, Eisenhower and then Kennedy authorised the CIA to create a Cuban exile military force to launch an invasion of Cuba to establish a regime that would suppress all pro-revolutionary forces and restore all US property (on the Guatemalan model).

Continued CIA actions after the failure of this Bay of Pigs invasion to overthrow the Cuban government, raids against Cuba, use of bacteriological warfare to destroy Cuban swine herds, organised sabotage campaigns against the Cuban economy, and plots to murder Fidel Castro (the last documented one in Angola in the mid-1970s) went on for the next three decades. Finally, the economic blockade was intensified against Cuba following the dismemberment of the Soviet Union.

The cost to the American people was first the spending over the last 54 years of billions of dollars of public funds in a futile attempt to destroy the Cuban revolution.

One must factor in the suffering of the Cuban people that these policies continue to produce. Finally, one might look at the loss to all of Latin America of what a policy of Cuban-American friendship and solidarity could have meant for the development of the region, given the outstanding achievements of Cuba in education and health care, connected to what the US has to offer in terms of technology, capital, and its own technical and professional workers. Also, the American people suffered a major blowback from the Cuban policy in the Watergate conspiracy (1971–74), in which former FBI and CIA agents organised a group of Cuban criminals who had worked in CIA terrorist actions against Cuba throughout the 1960s to wiretap phones and microfilm documents at the headquarters of the National Democratic Party in Washington. And the policy produced its spin-offs.

Indirect CIA intervention in the Dominican Republic to support Juan Bosch as a ‘democratic alternative’ to Fidel Castro and the Cuban revolution was then transformed into support for a right-wing military junta’s overthrow of Bosch when his government moved in a socialist direction and threatened the interests of US corporations. This was followed by an invasion by 25,000 US Marines in the name of defeating ‘communists’ after constitutionalist military officers sought to restore Bosch to the presidency he had won (1965). This was the largest direct military intervention by the US in Latin America in history, 32 years after FDR had formally repudiated the Platt Amendment.

The US also provided indirect support for a military coup in Brazil (1964), ousting a democratically elected progressive-oriented government. Finally, there was active support for military junta regimes in Venezuela, Argentina, Paraguay, etc., and either support for or opposition to civilian governments based on their subservience to US economic interests, all in the name of ‘containing’ the spread of ‘Soviet-directed Cuban communism’. Starting a year before the Cuban revolution, the CIA intervened in the Chilean elections of 1958, 1964, and 1970, funding opposition to the Popular Unity (Peoples Front) coalition of Socialist and Communist Parties and liberal groups led by Socialist Party leader Dr Salvador Allende. Unlike many Latin American countries, Chile had a history of free elections and an independent trade-union movement

The Nixon Administration launched economic/political war against Allende after his coalition won the 1970 elections, fomenting strikes and inflation, supporting rightist and ultra-left groups to destabilise the government, and creating the context for the bloody Pinochet coup and massacre of thousands of Popular Unity partisans. This was followed by economic aid and political support for the Pinochet regime as it destroyed trade unions, privatised Chilean social security, established with the ‘advice’ of economists associated with Milton Friedman a regime of ‘free-market fascism’, regarded by scholars of Latin America as the most brutal and repressive regime in Latin American history.

The return of gunboat diplomacy was seen most dramatically in the Reagan years by the ‘Contra War’ (Contras were elements of the former Somoza dictatorship, first established in 1934) against the revolutionary Sandinista government (established in 1978 and named after the martyred Augusto Sandino) in Nicaragua. The US also supported the more traditional ultra-right Salvadorian government against the revolutionary FSLN (Salvadorian National Liberation Front), thus running two ‘low-intensity wars’ (the new term of the 1980s) that claimed in excess of 120,000 lives in two small countries throughout the 1980s.

Blowback here came in the form of the Reagan Administration’s continued support for the Contra War, following the murder of US nuns in Nicaragua and passage of the Boland Amendment. This barred direct US aid to the Contras. Reagan also intensified surveillance of the US peace movement, especially The Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES).

In the 21st century, oil-rich Venezuela has been the target of US imperialist policies. The Bush Administration’s support for a failed coup against the government of Hugo Chavez (2002) was then followed by harassment as it moved in a socialist direction. Venezuela’s oil wealth and location offered and continues to offer its socialist-oriented government protection from direct gunboat diplomacy intervention, even after Chavez’s death, though US media continues to demonise his successors and does what it can to support the political opposition. Very recently, the Obama Administration has called for the normalisation of US–Cuban relations, something that is long overdue. The blockade, though, remains in tact and relations have in effect worsened, limiting expectations for a ‘new Good Neighbor Policy’ in the region.

In the Pacific, the US government was to be complicit in events that would claim an estimated 1 million lives in Indonesia in 1965. At first the US refused to aid the restoration of Dutch colonialism after the Second World War and supported Sukarno, a Japanese collaborator, as leader of an independent Indonesia, because of his opposition to the country’s Communist Party (1948).

This policy changed as Sukarno formed an informal alliance with the PKI against both Islamic conservatives and the military. The CIA supported assassination attempts against Sukarno in the 1950s and worked with conservative elements of the military against the Indonesian left in the fifth largest country in the world in terms of population at the time.

The US involved itself directly in the massacres of 1965, in which an estimated 1 million PKI activists, workers, peasants, and members of the ethnic Chinese minority were killed by the military and vigilantes linked to right-wing Islamic groups, as a counter-coup in response to an alleged PKI-supported coup.

The CIA would boast of its list of 10,000 key PKI cadres provided to the military, all of whom were allegedly murdered. US support for the brutal corrupt Suharto regime lasted for decades. Subsequently, the US denied all involvement in this sordid history after Suharto’s removal in 1998, claiming since the 9/11 attacks to represent the forces of liberty and democracy against ‘Islamic terrorism’ in Indonesia, although such groups are the successors to the Islamic vigilante groups that the CIA supported indirectly in 1965.

While most of this was then minimised in the US and the US/NATO bloc countries, in large part because the people massacred were communists and people of the left, Indonesia’s invasion and occupation of East Timor, supported by the US in 1975, became the source of an international protest movement.

East Timor, whose population is primarily Christian, had before the Indonesian invasion declared its independence from Portugal. Amnesty International has estimated that the Suharto Government murdered, with US-supplied weapons, as many as 200,000 of East Timor’s population of 700,000, while the US continued to support Indonesia’s ‘sovereignty’ over East Timor in the United Nations and blocked attempts to punish it for its crimes.

All Americans suffer in the eyes of history the costs of their government’s actions in funding, aiding and abetting what were two genocidal campaigns.

In the post-Second World War Middle East, the Cold War context was largely a distraction from what was and is the real issue: oil. First, the US replaced the British and French Empires, supporting British-installed monarchies in Egypt, Jordan, and Iraq. Working closely with the Saudi Arabian monarchy, centre of the world’s largest concentration of oil deposits, US oil companies established the Arab-American Oil Company (ARAMCO), a consortium to develop the oil.