Cuban History 8

Tribute to Father Sardiñas

Tribute to Father Sardiñas on the 55th Anniversary of his Passing

With the placing of a floral offering in the name of the Cuban people, and a pilgrimage to his tomb in the Colon Cemetary in Havana, Guillermo Isaías Sardiñas Menéndez, the priest known as the Father of the olive green cassock, was recalled yesterday on the 55th anniversary of his death

——————————————————————————–

Author: National Editor | internet@granma.cu

December 24, 2019 01:12:18

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Photo: Dunia Álvarez

With the placing of a floral offering in the name of the People of Cuba and a pilgrimage to his tomb, in the Colon Necropolis, in Havana, the priest Guillermo Isaías Sardiñas Menéndez, known as the Father of the olive green cassock, was evoked yesterday on the 55th anniversary of his death.

Major General José Carrillo Gómez, president of the Association of Combatants of the Cuban Revolution (acrc), highlighted the personality of the former chaplain of the Rebel Army who came down from the Sierra Maestra with the rank of Commander, while Monsignor Ramón Suárez Polcari, chancellor of the Archbishopric of Havana, said a prayer in tribute to this distinguished personality. Also present were Caridad Diego, head of the Office of Attention to Religious Affairs of the Central Committee of the Party, Brigadier General Delsa Esther Puebla Viltre and members of the Association of Combatants of the Cuban Revolution (ACRC), as well as representatives and religious leaders of our country. (National Editor)

Faure Chomón

Faure

By Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada

By Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada

December 7, 2019

Doctor in Philosophy and Letters, Cuban writer and politician. He was Ambassador to the UN and Chancellor of Cuba. For 20 years he presided over the National Assembly of the People’s Power of Cuba (Parliament).

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Faure stood out for his absolute loyalty to Fidel and Raúl, and his permanent defense of unity among revolutionaries. Photo: ACN.

Although it could happen at any time, the news of his departure causes pain and sadness. I feel the need to let those feelings flow now without dwelling on how much should be written about Faure Chomón and his decisive participation in the revolutionary cause of our people.

I met him shortly after beginning my studies at the University of Havana. He introduced us to Fructuoso Rodríguez, the inseparable companion of José Antonio Echeverría. Both engaged in an incessant struggle to transform academic life by stripping it of mediocrity and routine. At the same time, they fought to eliminate the consequences of the vices of the old politicking that hampered the revolutionary role that FEU had to play in the face of Batista’s dictatorship.

Faure led a small group that fought for these ideals, disseminating short mimeographed texts that they distributed from hand to hand.

They were uncertain times. We had to face the apoliticism and the demagogy, the frustration and the disbelief that the Republican bankruptcy had bequeathed us as a cursed inheritance. A new generation had to become its own teacher and undertake hard learning in very difficult and risky circumstances.

José Antonio and Fructuoso managed to rescue the FEU, created and directed the Revolutionary Directorate and, with their blood, they fertilized the route of freedom. Faure always accompanied them.

We fought together for half a century. In the final stage, he was advisor to the President of the National Assembly. He occupied a very modest space in the building that then housed the Parliament. We talked about the human and the divine on a daily basis. I always sought his advice, but more than as an advisor. He was always a loyal and sincere friend, a compañero of the old times. The hours went by reminding us of a glorious past that always went with us.

Others will wish him rest in peace. I know that he will continue to fight and we will continue together.

Why in Cuba No One Surrenders

Why in Cuba No One Surrenders

By Manuel E. Yepe

http://manuelyepe.wordpress.com/

Exclusive for the daily POR ESTO! of Merida, Mexico.

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann.

A decade ago, Cubans lost one of their most popular and beloved revolutionary heroes. This fact that was remembered with unused patriotic fervor on the West Indian island. On September 11, 2009, Juan Almeida Bosque, a Cuban patriot who had extraordinary merits in the struggle struggle that would have been enough to place him among the most exalted representatives of the Cuban people at any time in the history of the island, ceased to exist physically.

But in Almeida’s case, during his lifetime, the personality and talent of a young man from a very humble family, with black skin and a heart of gold with whom Cubans quickly sympathized. He barely transcended his leading role as part of the contingent that, led by Fidel Castro, led the popular battle against Fulgencio Batista’s tyranny leading to the successful liberation of the homeland from U.S. hegemonism and materializing Cuba’s second and definitive independence.

Some time before, Almeida had been one of the heroes followed by Fidel Castro in the attack on the Moncada Barracks. It was a feat that, despite being a failure in the military sense, ignited the spark that led to the triumph of the Cuban revolution and set the tone for the revolutionary changes that have shaken the continent since that July 26, 1953.

In the middle of 1960, I was working in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as Ambassador Introducer (Director of Protocol). It was a period in which Cuba, exercising the independence and sovereignty obtained for the people by the victorious revolution, responded as it could to the political and economic siege that the empire intended to impose against it on the continent. Cuba’s task was to develop diplomatic ties and friendship with other nations. I was assigned to accompany the recently-inaugurated Ambassador of the People’s Republic of Poland in his courtesy visit to the thenhead of the Rebel Army, Commander Juan Almeida Bosque.

This was one of the first meetings of the diplomat on the island with authorities of the highest level of the revolutionary government. He was a man who spoke fluent Spanish because he had learned it as a revolutionary fighter in the international brigades that defended the Spanish republic.

During the drive from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the temporary headquarters of the General Staff of the Army, on Avenida del Puerto (a building then occupied by the Revolutionary Navy), the European envoy requested, and obtained from me, information about the military and revolutionary trajectory of the then-Commander Juan Almeida Bosque. I had briefly introduced him as one of those whoh had attacked the Moncada Barracks, an expeditionary of the yacht Granma, and founder and chief of the Third Eastern Front of the Rebel Army in the Sierra Maestra and other merits for Almeida’s actions in combat that came to mind.

When I spoke of the bravery, discipline and modesty that made him one of the most beloved heroes of the revolution, I also mentioned, because it seemed important to me, to indicate his sensitive personality, Commander Almeida’s capacity as a musical composer

After the rigorous presentations and offering Almeida a welcome to the Ambassador, he used the word to express feelings of solidarity with the Cuban revolution and gratitude for the opportunity to make contact with one of its top figures.

Using the information recently received, the Ambassador galade knowledge about the political-revolutionary history of Almeida, but, to conclude, with the evident intention of emphasizing his expressions of sympathy, he affirmed to feel “great admiration for the hymns and combat marches that you compose”.

Commander Juan Almeida Bosque, without hesitation, responded by demonstrating his recognition for the diplomat’s declaration of solidarity with the Cuban revolution, and then, with a smile that showed understanding drawn on his face, clarified that although he made war… the musical pieces he composed were all love songs.

The diplomat blushed.

Without going back over the matter, there followed an in-depth conversation about the prospects of the ties between the nation represented by the Ambassador and Cuba, which concluded half an hour later with a cordial farewell.

As soon as we got into the car for the return trip, the Polish diplomat said into my ear: “You were too sparing in your praise. He is an extraordinary man. That’s why he composes love songs.

September 13, 2019

This article may be reproduced by citing the newspaper POR ESTO as the source.

Winston Churchill in Cuba

Winston Churchill in Cuba

By Ciro Bianchi Ross

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

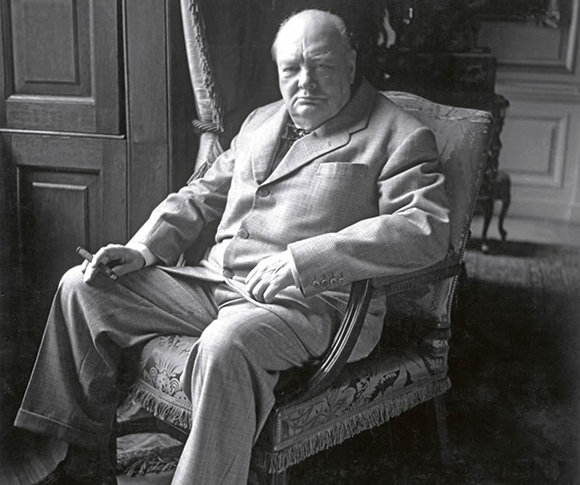

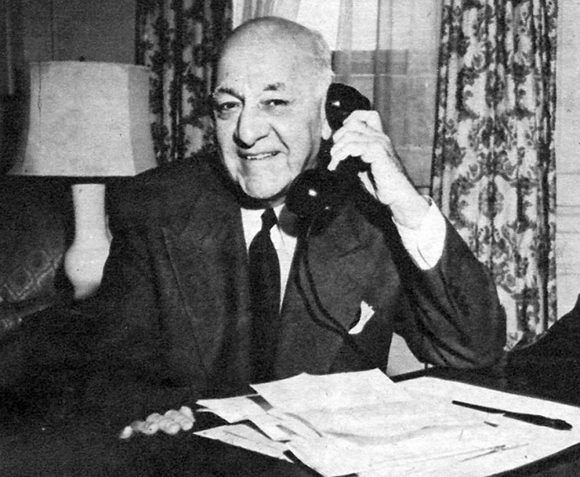

Winston Churchill. Photo: Diners magazine.

Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was given in Cuba, in 1946, the treatment of head of government, and the National Hotel reserved for him, of course, the Apartment of the Republic, which was intended for the most distinguished official guests. During the Second World War, the press had made his image of a good-natured and implacable grandfather habitual at the same time. He was an insatiable smoker of cigars. When he leaned out of the door of the Boeing 17 that brought him, he raised his right hand and with his index and middle fingers in the shape of a vee he greeted the crowd waiting for him at the Rancho Boyeros airport and applauded him enthusiastically: Sir Winston repeated for the Havana people the sign of victory, a gesture he coined throughout the war.

And there began the headaches for the Cuban protocol and the British legation in Havana, because the former premier did not respect timetables or formalities and was governed only by what the day had in store for him. He would get up at five in the morning and from that moment on he would put the entire hotel in check. One rainy day, annoyed because he could not take his usual dip in the pool, he suddenly ordered that they pack their bags to leave and asked them to get rid of them as soon as the sun came up. He spent his free time playing cards with anyone who wanted to join him. “He eats, drinks and smokes without restrictions of any kind. And in quantity,” wrote Enrique de la Osa in his report on the visit.

It was the second time Winston Churchill had visited our country. Many years ago, in 1895, he had celebrated his twenty-first birthday here. The then young officer of the fourth Regiment of Hussars came in his personal capacity to see the war that the Cubans were waging for their independence against Spain, and here the future Lord of the British Admiralty received his baptism of fire. At that time he also became fond of Cuban rum. He says so explicitly in his memoirs.

What was Winston Churchill looking for in 1895 in these lands? He said it clearly in his book: the adventure for the adventure itself. He was anxious to know what a war was like.

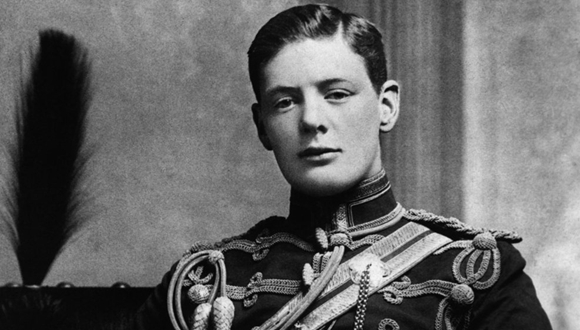

Young Winston Churchill. Photo: Archive.

Churchill came from Sancti Spiritus with a Spanish troop of three thousand men moving towards Arroyo Blanco. He marched on horseback for hours and made campaign life: he slept in a hammock, bivouacked with the troop, bathed in the rivers… Days passed and nothing happened, until one morning, at breakfast time, his group was surprised by a closed discharge coming out of the nearby forest and a horse that grazed peacefully next to Churchill received a fatal wound on the side.

The Spaniards rushed to where the shots came from and found no one. Churchill had already been warned that in Cuba the enemy was everywhere and nowhere… “When I witnessed all these operations I could not help but think that the bullet that had hit the horse had certainly passed one foot from my head. So, at least, it had been under fire. It was something,” says the former prime minister in his memoirs. He understood the situation: Spain would be ruined and bleed to death in front of a ragged army armed, above all, “with a terrible knife called a machete”. It was a weapon handled by soldiers for whom war “cost them nothing, apart from misery, dangers, and privations”. But even so, Churchill sympathized with Spain. Rather, he felt sorry for the Spaniards.

Winston Churchill with his wife during his stay at the National Hotel in Havana in February 1946.

Let’s go back to that Havana of February 1946. Churchill asked to be driven through the city in a convertible car and since Cuban protocol did not have a similar vehicle, the owner of the Partagás cigar factory offered his and he himself gladly served as a driver in exchange for the visitor reciprocating with a visit to his company, in which he was pleased. One of the traditional vitolas of the Romeo y Julieta brand bears the name of the British politician. Pinar del Río distinguished Churchill with the title of Favourite Son. He spent a whole afternoon locked up in the brothel of Marina, in Colón Street. His aide during his stay on the island was the then young lieutenant José Ramón Fernández.

Churchill’s lunch with President Grau San Martín, whose menu is still maintined, was tinged by the anecdote. Sir Winston left for the Presidential Palace with all the packing that the occasion required only to return to the hotel a few minutes later… I had forgotten the cigars. Then, another unplug: the retinue had to go round and round around the Palace for ten minutes so that the former premier and the president would meet at the scheduled time.

At the end of lunch, Grau forced Churchill to go out to the North Terrace before which many Havana citizens were waiting to greet him.

Churchill said: “I feel very pleased in this beautiful Island of Cuba where I have been so well received…”. And he continued, in Spanish: “I take the opportunity to say: Long live the Pearl of the Antilles!

At the end of his stay, he made another enthusiastic statement: “If I didn’t have to see President Truman, I would stay here for a month.

Churchill was an insatiable cigar smoker. Photo: Archive.

Youth Forum on Cuban Revolution’s History

Youth Forum on Cuban Revolution, 60 Years of History

The Forum will be organized around keynote speeches, central panels and workshops.

By Juventud Rebelde digital@juventudrebelde.cu

Posted: Friday 09 November 2018 | 10:06:51 pm.

Updated: Friday 09 November 2018 | 11:15:13 pm.

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

The triumph of the Cuban Revolution in January 1959 opened a new stage for national liberation movements. On an international scale, the humanist, anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist content, present in the important work of social transformation, modified collective images, reshaped politics and showed a cultural horizon that aspired to the complete emancipation of women and men.

Returning to the origins of that thought and practice is fundamental. Sixty years after that significant January 1st, the Young Communist League, student organizations, youth movements, with the support of the Publishers Abril and Ocean Sur, announce the Cuban Revolution Youth Forum, 60 years of history.

In a note sent to our editorial office, the 11 main themes of the meeting are specified, among which they are: The thoughts of José Martí, Fidel Castro, Raúl Castro, Ernesto Che Guevara and other figures; the United States-Cuba conflict; the historiography of the Cuban Revolution in power; the evolution of economic thought within the socialist transition, and the social policy of the Cuban Revolution.

The other topics of the forum will be: The international politics of the Cuban Revolution; the impact of social transformations in the last 60 years; institutionality, participation and socialism; social sciences in the Revolution; Marxism in the Cuban Revolution, and revolutionary journalism.

The event, which will take place on January 16, 17 and 18, 2019, in Havana, will be open to social scientists, teachers and university students, as well as other professionals who are linked to the topics they intend to address and have up to 35 years of age.

Those interested in participating should take into account the following requirements: send the abstracts of the works by e-mail (forojuvenil@ujc.cu), for evaluation by the organizing committee, before November 30, 2018; the abstracts will not exceed 250 words. They will be accompanied by the author’s general data including his location, the title of the paper and key words, and if accepted, before December 15 the papers will be sent for inclusion in the proceedings of the event.

It is also required that the Publishers Abril and Ocean Sur have the materials presented for the edition of a printed volume with a selection of these, while the Organizing Committee reserves the rights of admission to the Colloquium and will bear the costs of food and lodging for participants who are not from Havana.

The Forum will be organized from master conferences, central panels and workshops.

Julio Lobo, the King of Havana

Julio Lobo, the King of Havana

September 21, 2018

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

A biography of Julio Lobo has been published in the USA. It is titled The Sugar King of Havana and its author is John Paul Rathbone. We will dedicate today’s space to this character. He was the great figure of the Cuban bourgeoisie.

Lobo was born in Venezuela and brought to Havana when he was barely a year old. His father began to work very young in what would later become the Bank of Venezuela. Thanks to his efforts and intelligence, he gradually rose to management of the company when he was only 22. One day he had the bad idea of denying a loan to Venezuelan dictator Cipriano Castro and ended up in jail. Released at last, after three months of confinement, he was evicted from Caracas.

In New York, where he settled, the North American Trust Company immediately offered him the position of administrator of their Havana branch. A company that soon became the National Bank of Cuba, but was neither national nor Cuban. It was already the year 1900.

His son Julio studied in the United States and graduated as an agricultural engineer. He returned to Cuba and, in 1920, undertook the general management of Galban, Lobo y Compañía –his father’s business—which was the beginning and launching pad of his sugar empire. He became one of the richest men in Cuba.

If as a family group, the Falla Bonet’s surpassed him, Lobo was above them as an individual owner. He came to own 16 sugar mills, 22 warehouses, a sugar brokerage firm, a radio communications agency, a bank, a shipping company, an airline, an insurance company and an oil company. He was the main seller of sugar on the world market.

In his book Los propietarios de Cuba [The Owners of Cuba], Guillermo Jiménez attributes to Lobo a personal fortune of $85 million, with assets estimated at one hundred million. Rathbone, his biographer, assures us in his book that if that fortune were measured in today’s dollars it would amount to no less than $5 billion.

However, in 1960, Lobo left Havana –he would say– with a small suitcase and a toothbrush. He settled in New York and continued in the sugar business, but never repeated his past exploits. When he died in 1983, his capital, Rathbone says, was estimated at $200,000. In fact, according to the biographer, very few of his generation prospered in exile.

Unlike the Falla Bonets who, when the Revolution triumphed, took no less than forty million dollars out of Cuba, Julio Lobo, a furious nationalist, continued to invest in the sugar industry and other companies, while continuing to expand his valuable art collection. After all, he knew he had always been smarter than his rivals… but that trust led him to take no precautions whatsoever.

He never wanted to intervene in politics, but he was a convinced opponent of Batista. He was a supporter of Batista’s removal, without caring who would succeed him.

In 1957 he gave 50,000 pesos to the “Accion Libertadora”, an anti-Batista organization, which in turn gave half of that money to the “26th of July Movement”. This led him to believe that he could make conditions on the Revolution.

Rathbone assures his readers that Ernesto Che Guevara showed him otherwise. He summoned him to his office. The guerrilla commander, who had become president of the National Bank of Cuba, told him that they had reviewed his accounts and that Che congratulated him for the efficiency of his companies, and for not owing a single penny to the Treasury, but he also told him that his assets would be intervened. He made him an offer: He could remain at the head of his sugar mills. In exchange, he would receive a salary from the State. Needless to say, Lobo refused. It was then that he packed his small suitcase.

Lobo’s purchase, in 1958, of the three mills owned by Hershey was very controversial. This was a very expensive transaction, because, already in exile outside Cuba, his creditors demanded payment of the outstanding debt for those mills that were no longer his.

His specialized sugar library was the best and most complete in Cuba and perhaps in the whole world. His art gallery featured works by Da Vinci, Rafael, Miguel Ángel and Goya, among other great painters. His collection of incunabula and unique and rare books was famous.

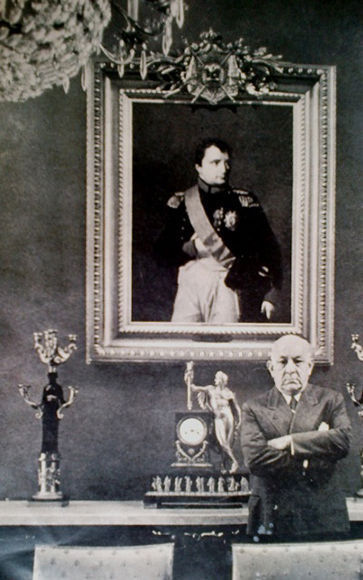

He was obsessed with the personality of Napoleon and came to possess a large collection of relics and more than 200,000 documents, which he left in deposit to the nation and which are treasured today in the Napoleonic Museum in Havana.

He was also interested in Hispanic-American subjects. Lobo was a Renaissance man, says Rathbone, extremely curious, with a deep knowledge of business, the subject of sugar, politics and history, and an impressive general culture.

He never had a yacht of his own and barely a social life. He was a compulsive worker, up to 16 hours a day. His hobby was gardening. He also had a penchant for collecting Hollywood actresses. He had a long relationship with Joan Fontaine and even proposed to Bette Davis. On one occasion he ordered that one of his swimming pools be filled with perfumed water to entertain the movie star and synchronized swimming diva Esther Williams.

He spent his final years caring for his first wife, whom he had divorced many years earlier. By then he could only move his eyes. He asked to be buried in a guayabera. A Cuban flag covered his coffin. That was his wish.

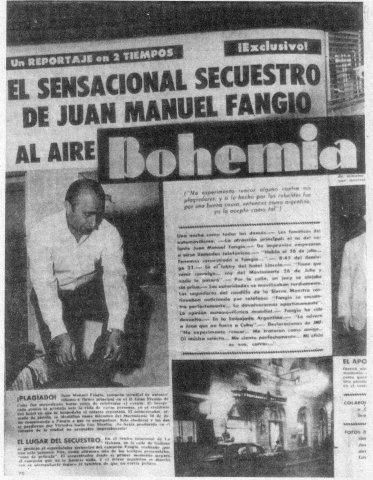

Manolo Núñez and the Fangio Kidnapping

Manolo Núñez and the Fangio Kidnapping

By Juan A. Martínez de Osaba y Goenaga

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

For Colonel Luis González

Manuel Núñez León, 89 years old and with seven children, is known as Manolo. He was born on September 4, 1928, at the El Rosario estate, today a Cooperative in the municipality of Puerto Esperanza. He currently lives alone in a modest house in San Vicente, between Palenque and Cueva del Indio, in Viñales. There, when he was able to locate him, Commander Faustino Pérez visited him several times.

It takes a lot of work to get words out of him that talk about himself. Always behind, against all bad things. In spite of accumulating so many years, he still has a prodigious memory and the same old mood, wearing a Carlos Gardel hat and a gray mustache. His life has been fascinating. Because of their way of being, those who pass by them cannot imagine the story they are carrying with them.

I asked him who his team was in the ball and he answered categorically: Pinar del Río. When I went further back, he repeated: Pinar del Río. After several inquisitions: “Well we were from Almendares, one was born like this”.

He is not satisfied with the film about that action: “I was invited to the presentation. When he finished they asked me what I thought and I said that some things didn’t happen like that and that the name of none of the members of the command didn’t appear. He silently accepted the explanation, because it is not purely historical, but fiction based on historical facts. He grimaced a couple of times and never came back.

The family lived next door to Los Cayos, where Antoñica Izquierdo was a transcendent figure for her preaching. They, plunged into ignorance and, in turn, helped by the enigmatic and kindly woman, took the sermons and began to heal themselves with cold water, or to try to heal themselves. Antonica, in her preaching, advised not to vote for corrupt governments, which brought her many consequences. That detail penetrated deeply into Manolo’s ideas.

The family did not vote and suffered the cruel eviction. They were placed on the side of the road with their articles and their gaze fixed on the sky, as if looking for a star to take them away or open the way for them. Several families were evicted in the style of Realengo 18 Oriental. From then on, life became much more difficult for them. Manolo recalls: “That area was owned by the landowner Pedro Blanco Torres, senator of the Republic, who demanded that they vote for him”.

According to her account, they sent thirteen wagons for thirteen families, which they took to a junction far from the Rosary, so that they could manage as best they could. The rural guard arrived and took some of the elderly prisoners to Pinar del Río. But the Cuban people have great solidarity and families in the new area took the “Bedouins” to their homes, especially the children.

Advised by several friends, he decided to go to Havana, but he was penniless. Then, in a conuco loan, he managed to sow and collect 100 quintals of malangas, which he sold for a peso each. And with the hundred pesos he went to the capital.

When I arrived in Havana, I joined the Orthodox Party of Eduardo Chibás, for which Fidel was running for the House of Representatives. I was accepted because of my revolutionary and peasant way. On Marianao’s 51st Street, Fidel made his last public speech to be elected. Coincidentally, when he finished, he called me and asked where I was from, what I was doing there and those things he was asking. I told him the story of my family and the Rosary Community. And look at the way things are, where he first came to my province, he went precisely to create the Cooperative in El Rosario. Maybe I had something to do with it. [1]

Then came the 1952 coup d’état, where all constitutional guarantees were closed and Manolo, along with other Orthodox militants, were left without a political compass, until they joined the July 26th Movement.

Juan Manuel Fangio, known as El Chueco and El Maestro, was born in Balcarce, Argentina, on June 24, 1911, and died in Buenos Aires on July 17, 1995, at the age of 84. He is considered one of the greatest motorist drivers in history and at his peak, the best.

Using the Alfa Romeo, Maserati, Mercedes Benz and Ferrari cars, as well as the Ford and Chevrolet, between 1929 and 1958 he was proclaimed five times Formula 1 world champion in the 1951, 1954, 1955, 1956 and 1957 editions.

Batista’s tyranny was trying its best to attract attention with some cultural and sporting activities, including boxing fights, as the popular uprising was growing stronger. Thus, in 1957, they designed the Cuban Grand Prix in motor racing. Fangio won unquestionably. The idea of kidnapping has been around ever since, but it was not possible for several reasons. The same could not happen now.

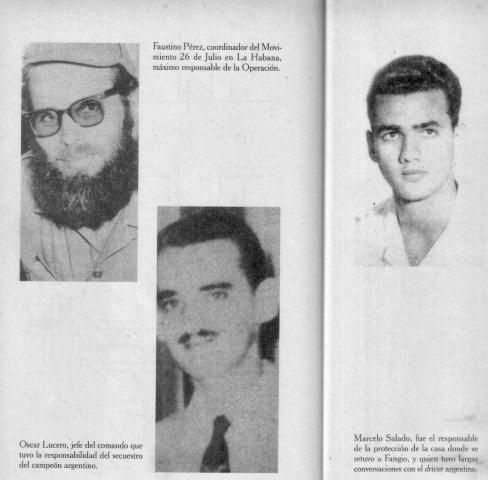

On February 24, 1958, the tyranny tried to re-edit the competition. Approved by the highest leadership of the July 26 Movement, Faustino Pérez, who was leading the underground struggle in Havana, planned a reckless action of universal significance and activated the command that would kidnap the great champion, led by Oscar Lucero.

The objectives set out were fulfilled to the letter: to protect the life of the champion with all our might, to demonstrate the upward force of the Revolution in arms, to avoid or minimize the connotation of the race and to draw the attention of the world to the fight against Batista.

First steps:

-It was planned to kidnap him on the exit of CMQ Television, but it could not be because of the public and the strong police protection. —The wagons were bet to execute the action; it was impossible. Among those mobilized was Manolo Núñez.

-On a visit of the champion to the National Hotel, but it was the most protected place.

-When I was walking along the route of the race around Havana’s Malecón, it was very well guarded.

And the time was passing. Then Faustino, a man of strong character and courage at all costs, said to Lucero, “You do it, or I will do it”. And from there the hero came out to accelerate the action. According to Arnol Rodriguez in his book Operation Fangio, Faustino later regretted speaking to a religious, disciplined and courageous man, who soon after became a martyr.

As is often the case, there are many versions of the event. From here we present Manolo Núñez’s:

On the night of February 23, 1958, a command of three cars (all with Thompson machine guns and handguns), loaded with three revolutionaries each and well-armed, stood in the vicinity of the Lincoln Hotel, where the champion was staying.

It was all in the blink of an eye. At 8:40 pm, Fangio went down to the hotel lobby and established his identification. The action has begun.

Manuel Uziel and Primitivo Aguilera entered the lobby and headed for the “Tres Molinos” bar. At the same time, several posts were erected. Manolo had to cover the entrance to the Hotel, machine gun in hand. Uziel approached the group where Fangio was and called him. The Argentinean was displeased: “Why do you want me?” Uziel then said: “I am from the 26th of July Movement and we are going to kidnap him”. After the surprise and with a gun to his side, the champion said, “Let’s go.

Some, perhaps from the protection team to the champion, moved suspiciously and Manolo’s voice echoed in the room: “If anyone moves again, I’ll shoot and there won’t be one left alive”. Uziel, without hesitation for a second, kept Fangio under gunfire and went out with him through the door of Virtudes Street. He then put the champion in the first car and started fast.

The hero’s eyes shine when he remembers his sentence: “We’ll be stationed here, and in five minutes nobody will leave, because nobody will die. And no one dared to leave.

The retreat took place in perfect organization, everyone went to the wagons stationed. This is what Arnol Rodríguez, who has already disappeared, tells us in the book quoted:

Immediately the three cars started moving along Virtudes Street. Oscar’s, the Black Monk, accompanied by his wife Blanquita, who was the closest to the hotel’s door, was the first one to start, although the car immediately got in front, driven by Primitivo Aguilera (El Pibe), accompanied by Manuel Uziel and Reinaldo Rodriguez, was a green Plymouth, the third a grey Buick with Carlos García (Cara Pálida) at the helm, occupied by Ángel Payá, Manolo Núñez and Ángel Luis Guiú (William)[2].

According to Manolo, Oscar Lucero’s return was the last one. There was only one obstacle, other than the kidnapping. The second one hit another and Carlos Garcia, the driver, had to go to the police station to testify. At Manolo’s initiative, they withdrew in time.

I immediately reacted: “Pale Face, you have to go with the man to the barracks because of the accident, give me your gun”. They left with the policeman, who never suspected the action, everything flowed normally. We walked along the path we were coming from and then Oscar Lucero’s car and his wife Blanquita picked us up and took us to the first place where they took Fangio: the house of Uziel.

Once at the station, the officer on duty asked them to agree among themselves, as the coup had been simple. Pale Face proposed to pay the man and everything was just as if nothing happened.

The authorities were afraid that the great champion would suffer some injury and even death, because the whole world would fall on them. They could not imagine one of the orientations: “Take care, no one should be hurt or killed, but first you, before Fangio, must protect the life of the champion at all costs…”

When I read the book of marras, I understood that in the things of life, chance plays a determining role. Maybe everything would have been pitiful. Let’s see how Arnol narrated a tragicomic anecdote in the definitive home of the New Vedado, which hosted the champion:

A few houses nearby, on the same block, lived a Tropicana dancer who was called the Mamboleta, a lover of Batista’s politician and ruler Rafael Díaz Balart. This motivated that at every moment, cars of the repressive forces parked almost in front of him, and it was the case that when Haydeé Santamaría Cuadrado and Armando Hart Dávalos, who was distracted, left the house, he went to one of those cars and only Haydeé’s quick reaction could prevent him from taking it. [4]

The outcome is known. Fangio felt at home and befriended his captors, who went out of their way to pay attention. The race took place without him and was one of the most cruel, as it skewed the lives of several fans, when a car at full speed lost control and was over the spectators. The great champion saw the accident on television and decided not to compete again.

That night of February 24, another command was created, now with the difficult and risky mission of returning Fangio.

Faustino’s order had been categorical: Well, come on, you yourself, Arnol, are responsible for the delivery. I don’t have to tell you anything else. Go in Emmita’s car and have Flavia (Berta Fernández Cuervo) accompany you. Only a few glasses were added to his usual clothing[5].

It was all just a matter of asking for it. At the proposal of the Argentine Embassy, the return was made in an apartment located at Calle 12, No. 20, 11th floor, between 1st and 3rd floor, El Vedado, in the home of Mario Zaballe, military attaché of that Embassy, who was outside the country.

That’s how Arnol remembered it:

After the doorbell rang, they opened the access door to the inside, we waited for the elevator and, once inside, we dialed the 11th floor. We penetrated and saw three lords of very serious countenances. Fangio immediately, changing his face and almost smiling, broke the ice, saying, “These are my kind kidnappers, my kidnapping friends.

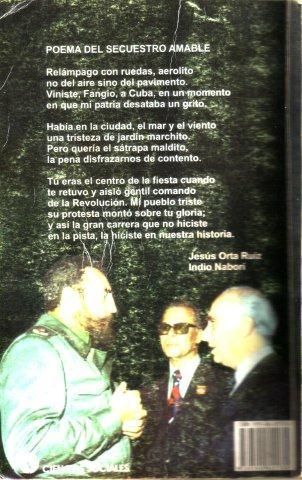

The culmination of one of the best prepared actions, with a popular and international connotation, as the press around the world turned to the kidnapping of the great champion, who ended up a friend of the revolutionaries because of the attention he received.

After 1959, Manolo Núñez, whom on October 17, 2017 we had as a guest at the Peña of the Scientific Veterinary Council of Pinar del Río, would obtain military degrees and fulfilled risky tasks in the Escambray Cleanup. Among other actions, he was in charge of taking the twelve Malagones to Ciudad Libertad, to place them under the command of Commander Camilo Cienfuegos.

The champion would visit Cuba in 1981 and met with the highest authorities, including his captors.

1] Manolo Núñez: Scientific Veterinary Council of Pinar del Río, October 17, 2017.

2] Arnol Rodriguez: Operation Fangio. Editorial Ciencias Sociales. Havana, pp. 31 and 32.

3] Manolo Núñez: Idem.

4] Arnol Rodriguez: Ob. Cit. p. 36.

5] Ibid.

6] Ibid.

Speech at La Demajagua (1998)

Speech by Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada,

President of the National Assembly of People’s Power,

at La Demajagua. 10 October 1998

Major of the Revolution Juan Almeida Bosque,

Fellow countrymen:

The idea, rather than the sunshine, brightened that morning:

“Fellow citizens, until this moment you have been my slaves. From now on, you are free as free as I am. Cuba needs from every one of her children to conquer her independence. Those of you who want to follow me, do follow me; those who want to stay, do stay; all will remain as free as the rest.

The announcement, emulated by all the land owners around Céspedes on 10 in the October 1868, would strongly mark the nature of the war.

With those words, right here, 130 years ago today, the Cuban nation started to move ahead in our own a only Revolution began, which would be continued thereafter by successive generations of Cubans, and for almost a century would squander feats, withstand defeats and sacrifices until victory was achieved.

Born from the unlimited love of justice, equality and human dignity, it knew how to stoically cope with the worst adversaries and learn how to stand up to them, without even relinquishing its ideals. It inspired men to bequeath everything and to fight to the bitter end, without anybody’s help, following the example of that who on a day like this called everyone of us to start out. This same Revolution that 130 years later, dealing with similar obstacles resists, preserves and triumphs, and can recognize the path it has gone along as the best tribute to those who took history by storm on 10 October 1868.

In that society poisoned by the slaves system, freeing the slaves and openly proclaiming it is in its first act imparted the emerging movement the deepest radical nature, placed its face to face with the primary problem of that time. But Céspedes would not just break the chains that oppressed those men. He went, all the ones, or beyond. He turns them into citizens with exactly the same rights as the rest. He defines the homeland as an ideal, as a project for me the holy to blacks and whites, two former masters inserts, and urged all of them all and exactly the same wording to fight the last four of the last La Belle was not calling them to work, nor was it just announcing freedom calling it was an invitation person for foremost to the creation of a common work.

It was the founding of the only true democracy, on that does not recognize privileges, that rejects prejudices, stresses virtue, trusts men and incorporates everyone.

It was the birth, then, of the Republic of Cuba and the outset of the struggle to conquer the Homeland.

Slavery was the decisive question that defined Cubans. The despicable exploitation of human beings was the main source of the wealth of the criollo well-to-do and the fuel for the colonial regime.

Slavery had been present, all over the century, in our intellectuals’ and politicians’ reflections. It would always come up as the dominant subject in the projects to reform the colonial system, in the attempts to change relations with the Metropolis, in the plans to design the Island’s future and would weigh heavily thereafter, during the war itself.

It was also linked to the core question at the time when Cuba was emerging as a distinct identity and which should forcibly separate from Spain. Who were the Cubans? Who made up that new people?

It is necessary to deepen into our history if we are to understand the meaning of what happened that day and to fathom the complexity of a problem that would not solve with a noble act, of incomparable altruism, or with its formal proclamation. It would demand a struggle that would require tenacity, staunchness and wisdom. It would be part and parcel of the war itself; it would most strongly mark it and determine the future course of our life as a people.

The La Demajagua message, issued by a group of white landowners, entailed a total break with the line of thinking and behavior on slavery and blacks maintained by the reformist sectors, including those with more advanced ideas.

Its real forerunners were not those groups, but slaves who more than once had revolted against the abominable system. The Matanzas province risings in 1843, butchered in a sea of blood, shook the colonial society.

Those rebellions would cause fear amongst reformists, the wealthy criollos who sought to change the gloomy society in which they lived but who, at the same time, would not go beyond that which an anachronic and obscurantist empire would be able to grant them. Slave masters could demand nothing from their colonial masters. The most important separatist attempts promoted by them sought to perpetuate slavery and annex the island to the United States. Notably, their main actions were armed expeditions, openly organized and prepared in the U.S. territory; from where they left for happen afterward with the efforts to be made from there by emigrant patriots. Also, most of those expeditioners were foreigners; very few Cuban-born people participated with them.

On the other hand, for slaves -subjected to the cruelest exploitation, isolated in their barracks, with no access to education, lacking the means to communicate their demands and organize themselves- it was virtually impossible to assume the leadership of a nation-wide struggle. They could – and did in fact many of a time rebel against their masters and punish them or flee to the woods. But they were not in a position to turn their struggle into a movement that would get other forces together to conquer equality and, with it, political independence the warranty for justice to be real and conclusive.

That space could only be filled by criollos freed slaves, craftsmen and landowners who were willing not only to abolish slavery altogether but also to incorporate the emancipated people to the common national project. It was not enough to oppose the slave trade or to criticize the excesses of human serfdom.

It was not a matter of compassion, philanthropy or economic calculation. If the purpose was to build a nation as demanded by the evolution reached by the colonial society, it was imperative to recognize the human factors constituting it and to attain their full integration.

A total abolition of slavery in all of its forms and manifestations, a true emancipation of full exercise of citizenship – with the same civic and political rights as the other men-, the elimination of racism, including prejudices and discrimination, where the demands posed by history and could only be assumed by a deeply and truly revolutionary movement.

The essence of that movement would have to be justice and solidarity. It was La Demajagua’s main message. It would thus be proclaimed, years later, by Antonio Maceo when he said that on October 10, 1868 “Cuba flew the flag of war for justice.”

That morning, before their liberator, there were scarcely twenty slaves, which was his full endowment. So it was not a decision significant in concrete military terms. The aim was not to set u pa major detachment with them to march on Yara, the goal of the then-emerging Liberation Army. Twenty men was nothing compared to 100,000 colonialist troops, or to the hundreds of thousands of slaves that there were on the Island. But it was to that mass and to their masters, precisely, that the message was for.

It was the beginning of a complex process –that would have ups and downs- which would see a quest to firmly stick to principles and to incorporate, as much as possible, other elements, without excluding the planters from western Cuba. The unequal balance of forces facing patriots forced them to do that, but loyalty to their own ideals made them keep a radical and consistent path even at the early stage.

At La Demajagua, a channel had been opened that would allow slaves and sincere abolitionists to move ahead of the sugar oligarchy’s hostility and of fears and inconsistencies present also amongst the revolutionary ranks.

On 28 October, the Bayamo municipal government would unanimously decree immediate abolition. In April 1869, the Guáimaro Constitution would enshrine freedom for all Cubans and the end of slavery, but a subsequent House of Representatives agreement –on July 5- would keep former slaves subjected by forcing them to continue to work through the Freed Slaves Rules.

Céspedes would annul it on 25 December 1870. It was this decision that ended slaver –conclusively and completely all over the Republic’s territory- , including covert slavery under the so-called Patronato. Before that, on March 10, the Revolutionary Government had declared null and void the Chinese colonization contracts, a hardly disguised form of servitude.

Thus –indicated Céspedes- their “natural capacity as free men was restituted, exercising their personality in its entirety, enjoying the same civil and political rights as the other citizens in perfect equality. “

Complete abolitionism had triumphed and would be the rule within the territory liberated by the Republic in arms. However, it would have to go on fighting bitter battles against the landowners who, in the western region, controlled most of the country’s riches, and against their agents who amongst émigrés, would promote divisiveness and plot against the Revolution, to deviate it from its course.

The La Demajagua message reached all Cubans. One of the main representatives of reformist landowners went as far as asserting, on 2, October 1868 that “never before had Cuba been closer to a true social and socialist revolution.”

General Dulce, for his part, in a decree he issued on 12 February 1869 –to then unleash the fiercest repression of the fighters for independence and of all those who supported them- included amount the serious crimes of “infidelity”, insurrection, conspiracy and sedition, those of “coalitions and leagues of day laborers and workers”.

That is why, among the first freedom martyrs were, on 9 April that year, several tobacco workers, members of the guild called Gremio de Laborantes (day laborer’s guild), A Havana secret society, who found their death at the vile pillory. One of them, Francisco de León, at the foot of the gallows, delivered a fervent speech that ended with wishes of long life to the independence of Cuba and to Carlos Manuel de Céspedes.

Repressive action focused especially on the association of tobacco workers, core of the Cuban emerging workers’ movement, which had gone on strike several times since 1865 and whose newspapers were suppressed.

An irrational violence was unleashed against the Havana population as a whole, which suffered the terror caused by incidents like those of the Villanueva and Tacón theaters and the Louvre walkway, and later the murder of the medical students.

General repression triggered the exodus of an important part of the Cuban population. According to a Spanish historian, only between February and September 1869, over 100,000 people left the country through the port of Havana.

Among them were moneyed families, but also important groups of workers. That emigration would have been an indispensable support for the Revolution, but it could not unite to fight the big landowners’ annexationist intrigues and the Washington Government’s systematic opposition.

Emigrant workers made generous contributions from their salaries for the purchase of weapons and the preparation of expeditions. They devoted their time to defend the Cuban cause and many of them laid down their lives in combat. Of all 156 expeditioners aboard the Virginius, 47 were workers, 23 of them of the tobacco sector.

The emigration question would be a decisive factor in the war’s unfolding. As to the wealthiest landowners who had left the country, their relations with the Revolution would be a reflection of the attitude towards the Revolution maintained by that sector which controlled the Island’s greatest riches, concentrated in its western region. The Junta de New York was an extension of the Junta de La Habana and an expression of its interests closely linked to slave production. Despite the many efforts that the Orient and Camagüey people made with them –since before October 10 and which would go on after the Revolutionary Government was in place- the war could not move into the west, where several risings by local patriots were discouraged and aborted in different ways by the capital’s leaders.

Their behavior was opportunistic and treacherous. They appeared to support the Revolution as long as it took place away from their properties and actually supported it only in hopes of getting concessions from Spain or in wait for a Yankee intervention to annex the island to the United States.

This group was essentially annexationist and its positions on the social and racial questions never went beyond the lines of reformism. This led to one of the most dramatic aspects of that war and to one of the main causes of defeat. The bloodiest, longest and most devastating war in the Americas had a theater of operations limited to the country’s poorer and less developed half.

The conflict was not reflected in the colony’s sugar production, which kept basically the same levels over those ten years, except for some variations caused by the situation on the world market. This goes to show that, in this time period, Cuba’s western planters –Spainiards and criollols- saw an increase in their profits obtained from slave labor whereas the rest of the country was bleeding dry for freedom.

To regard the War of 1868 as a landowner’s and criollos bourgeoisie’s movement –a flaw some have made- is to not look at things in-depth. In the history of Cuba there was never a chance for a bourgeois revolution because in this country there never was, as a class, a national bourgeoisie. The men who started the Revolution cam by birth from that class, but they did not implement its policies or served its interests. The fathers of the Revolution –Céspedes in the first place- represented from the outset the people’s –including the slave population’s- aspirations; they merged with them and brought them along to the movement’s leadership at all levels.

If one were to point out that those men, from the family origin viewpoint, were our patricians, one would have to note that they were part of a Jacobinic patriciate capable of radicalization, along with the exploited masses, at the pace the process was moving on.

Furthermore, the Metropolis’ clumsy policies and the outrages committed by the mobs of voluntaries in the cities, particularly in Havana, placed many of those planters in difficult situations and, in some cases damaged their property and made them victims of repression. From the revolutionaries’ perspective, that reality justified the efforts to bring them to join in the cause, to seek their support or to neutralize them.

The Revolution was also desperately in need for imperative resources from abroad. It also needed solidarity and international support for its lonesome struggle. Learned Cubans, trained for diplomatic work and propaganda, were not many then. The best from the country’s central and eastern parts were fighting at war. The best from the west had emigrated.

All those factors were the backdrop of the complex, contradictory and difficult relationship that there would be amongst the wealthy émigrés and the Republic in arms. As a rule, when it comes down to the Great War and its internal conflicts, three factors are mentioned; the Liberation Army, the revolutionary Government and the House of Representatives. But a fourth factor is to be added; and it was emigration, which had a close connection with the others and played a major role by action and default in the course of events.

There would be no time here to go deeper into this important issue. I will just point out that, in those years, the group of leading exiled planters, controlled by annexationists, had a preeminent influence over emigration as a whole. It included Céspedes’s bitterest enemies, who publicly opposed his policies and were part of the conspiracy that brought him down from the presidency.

Most of the emigration was made up of poor craftsmen and workers, just arrived at a racist society, still struggling for their life in an alien and hostile environment. It was a profoundly Céspedesite mass that regarded the La Demajagua man as their liberator, that admired his generous sacrifice and understood his intransigence against exploiters and his love for justice.

His opinions were voiced in publications that denounced the annexationist and slavery advocates’ maneuvers by the Junta de New York. That city’s working women expressed their feelings through the sword the bestowed on Céspedes, which he did not accept out of modesty.

In a lovely gesture, artisans expressed their support by agreeing to economically support the Homeland’s Father’s wife and little children. This action prompted a greater gesture from Céspedes and a clarification of his thinking when, on declining the offer, he said that he wanted his family to follow in their steps by “working for a living and contributing if possible with their savings to the Republic’s funds”.

New York’s Sociedad de Artesanos Cubanos, the representative of the then emerging Cuban proletariat, would elevate its protest for the Republic in arms President’s deposition, which it had denounced and rejected even before it took place.

That mass of poor men and women would be the support of the revolutionary efforts during the Ten Year’s War, when the plantation owners stepped back to wait for the Yankee intervention, and they would continue to do so in the future attempts; would support Marti’s Party and would continue to fight until 1898. The truth is that over those thirty years, as Máximo Gómez acknowledged, “the combatants’ last hope of salvation is always the cigar roller’s knife”.

The colonial repression broke loose with a unique rage against defenseless towns, trying to wipe out all forms of collaboration with the Liberation Army.

Among the measures adopted by Captain-General Dulce in 1869 and denounced by Céspedes to the world were “the confiscation of assets of republican army members and of those suspect of being friendly to the revolution, the compulsory collection of horses from all rural farms in all rebelled districts… The reconcentration, also compulsory, of all population in rural settlement and the subsequent abandonment of farms, the ruin of all corps and fields to devoid the patriots from foodstuff, the arrest and immediate execution of all Cubans found in the fields, both armed and unarmed”.

An Irish journalist who visited the island during the war left testimony of the desolating picture he found in the Las Villas towns: “most of the population is in the saddest stage of misery as a result to the severe orders given by the Spaniards for the reconcentration of people in towns and villages, concentration that has resulted in families being ravaged by hunger and disease”. And on his arrival at Sancti Spíritus, that author wrote: “There one could see, asking for a bit of rice from door to door, lines of women whose faces showed the unerasable signs of hunger and in many of them you could read sad stories of sufferings and hardships”

Extending the war to the rest of the country, achieving an effective integration of all territories and getting the indispensable war resources from abroad were strategic needs that the Revolution had to meet to consolidate itself and triumph.

Those objectives came face to face with not only the colonialists’ power but also the anti-national oligarchy and the US government.

It is recorded in American official documents that between March and November 1869, the entire federal Government machinery was mobilized in 16 States, from Florida and the Gulf of Mexico up to the Canadian border, with the active participation of the Navy, to thwart expeditions, stop ships, seize weapons and pursue, arrest and punish the patriots.

The authorities’ hostility towards the Cuban cause contrasted with American people’s manifestation of communion and support. For instance, in its report of 14 June 1870 the House of Representatives’ Foreign Relations Committee included numerous annexes with belligerence in and independence of Cuba. They came from different parts of the United States and were backed by tens of thousands of people’s signatures. One of those letters was signed by 72,384 New Yorkers.

The official attitude counter to the feeling of so many Americans would be expressed, at that time, in an address to the Congress where President Ulysses Grant rejected any assistance for the Cuban patriots, about whom he used the most slanderous and vulgar of languages.

Back in 1870 Céspedes had warned that the US Government’s “aspiration is to take possession of Cuba without dangerous complications for its nation and while it remains under Spanish rule, even if it is to become an independent power; that is the secret of its policy”.

In a message to Benito Juárez, on 13 December 1870, Céspedes said “you certainly know only too well how terrible are the efforts we are engaged in to secure our national rights and how big are the difficulties we have to overcome, for you know that our enemies are great many and well disciplined, that we have to fight in a quite narrow island, that the coastline is patrolled by a large fleet; and that we are abandoned to our own resources in spite of being at the very center of the independent America”.

Two days later, in a letter to a New York newspaper editor, Céspedes denounced that while Spain can easily procure everything it needs for the war, the Cuban patriots are persecuted and “their ships and weapons –bought out of their patriotism and with our women’s tears and our brave soldiers’ blood-are seized”.

The persecution of immigrants in the United States and the authorities’ actions to prevent any aid from there to the revolutionary movement reached its highest expression with the proclamation issued on 12 October 1871 by President Grant himself. Alleging that the revolutionaries’ activities violated United States laws, he threatened them with these words: “which is why they are subject to be punished, will be most severely pursued without possibly be punished, will be most severely pursued without possibly expecting mercy from the Executive to save them from the consequences of their crime, if convicted. And I admonish and consequences of their crime, if convicted. And I admonish and encourage every authority of this Government, civilian, military or naval, to use every means within their reach in order to apprehend, try and punish each and every one of such criminals, transgressors of the laws that impose upon us sacred obligations to all friendly Powers”.

Mister Grant’s threats were dramatically realized when the Yankee authorities confiscated the ship Pioneer and all the weapons it was carrying to Cuba. The Homeland’s Father gave instructions then, on 30 November 1872, to withdraw the unofficial diplomatic representation that the Revolution had set up to at least seek the acknowledgement of our belligerence. In doing this, he left history these words of permanent validity: “It was no longer possible to put up with the contempt with which the United States Government was treating us, a contempt that increased as our sufferings increased. For long enough we have played the beggar who gets the alms repeatedly denied, and who gets the doors slammed insolently on his face. The Pioneer case has come to break the back of our patience: not because we are weak and unfortunate should we stop having dignity”.

While obstructing solitary actions from the Cuban immigration, the United States facilitated the colonialists’ continuation of the war with the use of the American territory and industry. With this support, Spain deployed up to 83 warships to block Cuban coasts, including 30 stem gun boats, built, armed and equipped in the United States.

In a message to the president of the U.S. Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee which constitutes a profound analysis of the war’s development, on 10 August 1871, Céspedes had unmasked Washington’s policies: “that Republic’s Government… no longer being a mere spectator indifferent to the barbarities and cruelties executed before its eyes.. but now providing indirect, moral and material support to the oppressor against the oppressed, the strong against the weak, the Monarchy against the Republic, the European Metropolis against the colonial America, the hard-line slavery advocator against the liberator of hundreds of thousands of thousands of slaves”.

Comrades all:

After 1898, when the Yankee intervention brutally interrupted the eliminate them from the memory of the people, to lessen the meaning of their struggle and hide the true nature of the problems they had, the way they faced them and the solutions they found.

Stressed were the different points of view on various issues that, at times, some of the main protagonists of the epic had. Any analysis was eliminated from the evolution of those opinions and the context in which they came to be. Everything was reduced to inevitable personality differences. In fact, it was the human passions that explained the failure of a ten-year war. They wanted us to believe that, in the end, it was our own characteristics as a people with explained the failure of a ten-year war. They wanted us to believe that, in the end, it was our own characteristics as a people what explained the defeats we suffered. They were trying to introduce in the collective psychology the fatalism that has always been used by the annexationists to justify docility to their masters.

In 1868 there was no nation or a national conscience. We were a heterogeneous, shapeless mass, out of which the people would emerge in the middle of the struggle and would identify itself through the struggle, thus acquiring its definite identity.

Those men did create the nation, forge the people, make the reality of Cubanness come true. Was it possible to do it with no discussion or passionately contrasting ideas?

Many times concepts were repeated to us that were like an echo of the distortions and slanders given at its time by the colonial and the US government’s propaganda of the events and their participants.

Céspedes –supposedly authoritarian- accepted, however, the majority’s criterion at Guáimaro, and later observed the House’s deeply unjust and mistaken decision to depose him. He who was presented as a militarist did his best, as far as possible, to regularize the war and make it more humane. An all-out abolitionist, he made tactical concessions in the initial phase two attract or neutralize western planters.

But he never hesitated to fully exert his powers when the principles were at stake for it was necessary to secure the advance of the Revolution. He did it on 10 October 1869, on the struggle’s first anniversary, when he ordered the Liberation Army the burning of all sugarcane and coffee fields, when he commanded that, in a Las Villas invasion, properties be burned and that slaves be brought to the rebel and accepted in the patriotic ranks were sent to Camagüey to protect them from their former owners; also when he annulled the House’s agreement that governs the life of freed slaves, thus definitely eliminating the servitude system; when he appointed two blacks as alderman in Bayamo, Cuba’s first liberated city and home to the Revolutionary government; when he promoted Antonio Maceo and Máximo Gómez to generals and blacks and mulattos who were former slaves and from the poorest sectors of people to high military ranks; when he decreed, on 15 February 1871, that traitors be considered all those who took part in any negotiation that did not observe Cuba’s absolute independence and the complete abolition of slavery.

These positions and Céspedes efforts to eliminate regionalism, to lead the invasion to the west and his support for the most radical sectors in the exile in their opposition to the planters annexationists maneuvering, place me as the starter of a consistent revolutionary line that would later continue with a Protest of Baraguá, with José Marti’s revolutionary work and with other people’s unending struggle until the victory of January 1st and these glorious fourty years in which, under Fidel’s Céspedesite leadership, the people at last saw the La Demajagua come true.

The goals of independence and justice of the Cuban Revolution that started on 10 October 1868 were attainable in the first phase. To realize them there would have to be a national consensus, a Party to lead and integrate the political and military struggle and a fighting strategy to be spread throughout the entire island. These objectives would be later achieved with Marti’s indefatigable genius and work.

But the Apostle’s work would have never been possible without the Ten Years’ War, because it was that War that forged our nationality, radically transformed the colonial society and turned the exploited masses into the propagandists of their history.

Before 10 October 1868 there was different criteria as to the time to commence the war, and from that moment on, up until April 1869, there were diverging ideas as to the strategy to be followed and the organization of a revolutionary power, they’re being two main centers in Oriente and Camagüey, two leaderships, two armies in the event two wives. It is true that that Guámimaro they discussed deeply; they surely had to discuss passionately because they were trying to design the Homeland into the find a way to get there. But most important of all is that, with everybody’s concord, Guámimaro produced only one Revolutionary Government, with only one program, only one Army had only one flag. At Guámimaro prevailed, above all, the sense of the indispensable unity, the common will to set aside the differences and to add up everyone’s energies for the common battle.

Céspedes and Ignacio Agramonte, the main chiefs of that period, were symbols of the two initial notions regarding no revolutionary power’s organization which were ex needs some worry. But after his thesis triumphed Guámimaro, Agramonte himself would criticize, amid his brilliant military campaign, the House’s interference with the condition of the war and would claim for the indispensable sing single command to lead it. On 14 January 1871, after stating that there were “contradictory opinions but no divisions war concessions”, the celebrated Camagueyan added “I am one of those who think it most and necessary to replace the officials for delaying the expeditious and energetic advance of our military operations… “ There up use plenty of evidence that as they advanced in the war, all relationship of mutual understanding was growing between Céspedes and Agramonte. In the Homeland’s Father’s epistolary there was proof of his happiness in this regard and he dedicated words of admiration and affection to Agramonte.

Just as Fidel had explained, should Agramonte have been alive, he would have opposed and probably prevented Céspedes from being disposed by the House of Representatives. The historical truth is that when he fell in Jimaguayú, the Homeland’s Father lost a decisive support, the most eminent disciple, he who should be his successor.

The 1898 Imperialists you search and frustrated the movement initiated here 30 years before. The two possession of the country and its resources, planned to correct and US-client regimes that exploited and divided the people. In that base Republic remaining the colonial society’s worst vices. There was no hold tight servitude of millions of Cubans suffered capitalist slavery and along with it, misery, helplessness, racism end radical discrimination.

There were six decades of ignominy, radical negation of the 1868 ideals. That republic was the opposite of La Demajagua; it had nothing to do with Céspedes an Agramonte’s dreams for wit that heroism, the sacrifices in the light should buy hundreds of thousands of Cubans over three decades.

Today’s youth, who learned to love and respect are glorious founding fathers, will find it difficult to imagine that it was not always like this. Under the Yankee domination regime, they tried to steal their memories from the public, your history was distorted, they tried to dissolve into forgetfulness the example of their heroes in the lessons of their struggle.

The neo-colony and its masters were specially in place a ball with Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. Since that regime was the most opposite to patriotism, they had to make sure of the Homeland Father’s eternal death, have him completely disappeared from history, for forever buried his message.

There you have all the data in archives and libraries. Céspedes is thought, his political documents, his ample correspondence, his literary work was more publicized over the 30 years of war than after the date the intervention. Over 60 years in the so-called Republic of Cuba use only published, together with works by other offers, a tiny portion of his political work in one book for circulation appeared in 1938 under the title Breve Antologia del 10 de Octubre (Brief Anthology of 10 October). On Céspedes, over sixty years, were published 3 books, 3 booklets and 24 newspaper articles, not always fair to him.

Numberless were, however, the biographies, studies and tax of former annexationists and autonomists that came out of Cuban printing shops during the same period.

Also, to those characters were dedicated statues and monuments, and streets and squares were named after them.

But not to Céspedes. It is true that Manzanillo zealously took care of the Bell and the Bayamo and Santiago, witnesses of his immolation, mark some places with his glorious name. But the rulers of the time, for sixty years, did not pay any tribute to his memory, outside his tomb.

It is good that our young thing about it. It illustrates on the meaning of our said terry and struggle in our single revolution, the one initiated by the man who the enemies of the homeland wants to destroy and disappear. It also reminds us of how he continued to fight even after he fell in San Lorenzo.

He who always foresaw his death before the triumph and had warned us that he would come out of his two as many times as necessary to our minds Cubans of their duties for the homeland, continue to call on the young and the two patriots to retake the La Demajagua road.

This is why his first monument in Havana, a humble plaster bust, was built and put at the entrance of Vibora’s Secondary Education iIstitute in 1949, paid for by his teachers, students and workers, penny upon penny. This is why in 1947 Fidel Castro and the University Students’ Federation took the glorious bell to the university campus and rescued it from political maneuverings they denounced of a memorable acts in the capital and in Manzanillo. This is why, in 1956 Emilo Roig, exemplary teacher, took that autocrat king from the seat where he was still honored by the spurious republic and replaced him with the Homeland’s founder.

Only after 1959, when the Revolution that he initiated triumphed, his work and thought was finally rescued and extensively spread. Today, for the Cuban people his exemplary life and his ideas are they in the spring where the pure water of patriotism and the virtues and value of Cubanness always flow.

In this same place, thirty years ago, our Commander- in-Chief gave an essential speech. He defined our history’s greatest truth, one so many have tried to hide in various ways: that there has only been one Revolution in Cuba, the one undertaken by Céspedes on 10 October. Fidel summed up the insoluble continuity of our historic process with this admirable phrase: “We, then, would have been like them. They, today, would have been like us”.

Being like them, today, when the threatened homeland is faced with powerful enemies, just like then, when we have to face fifth up the dangers of confusion and overseas fostered hesitations, means, first and foremost, to revive the La Demajagua message and to turn it into a way out of behavior, into a guidance for the present revolutionary action.

Unyielding defense of the Homeland’s absolute independence, without concessions of eight times that might damage our national dignity; true unity, real, intimate among all Cubans, and the elimination of every trace of discrimination or prejudice that may separate us; indefatigable struggle for equality and solitary amongst people, founded upon the ethics of sacrifice, abnegation and virtue.

This is the legacy left us by our common Father, the founder, the internal President of the Homeland.

He who told us that “those were not willing to sacrifice everything, everything for the freedom of the homeland are not revolutionaries”, their rich planter and gave up his wealth and laid down all his personal to rate for the revolutionary cause. He was sacrificed his family and promised to leave them with “an inheritance lacking in money but plentiful of civic virtues”, they enlightened man, the poet, that until the eve of his death was teaching to read and write with rude instruments that he would bring out of the woods; the Manzanillo and Bayamo Symphonic Orchestra organizer who in his last refuge in the Sierra Maestra admired the dances that former servants rehearsed for him; he who called the black man brother in the worker comrade; he who was unyielding loyal to the Revolution despite the injustice, abandonment and ingratitude he suffered; he who fought to the last minute, completely by himself, almost blind and surrendered by enemy soldiers.

At this time when they are trying to take the sentiments of justice out of men’s hearts, in a world where selfishness and greed are trying to be imposed, the Cuban Revolution continues to be our people’s only road and carries indispensable values for humanity. In the middle of the war, Céspedes drew a clear line between Cuba and colonialism, and outlined that insurmountable line that separates us today, even more clearly, from the imperialist. The enemy “fights to sustain slavery of the black, to spread obscurantism, to perpetuate iniquity; the Cuban patriots fight for all men’s freedom, for the triumph of justice, for the enthroning of civilization; out go the greed, the ignominy, the night, here come the reason, the truth, the light”.

Today’s and tomorrow’s Cubans will continue to defend the Homeland founded here, the Revolution started on 10 October, our Socialism that and this sacred land took its strongest roots. We will continue to fight ever on to victory.

Long live free Cuba!

Independence or Death!

SCANNED FROM 1998 PAMPHLET in 2018.

“Printed by the printing section of the

National Assembly of People’s Power”

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||

You must be logged in to post a comment.