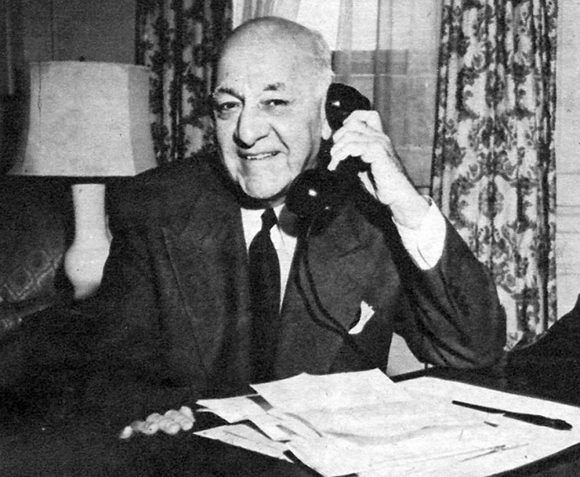

Julio Lobo, the King of Havana

September 21, 2018

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

A biography of Julio Lobo has been published in the USA. It is titled The Sugar King of Havana and its author is John Paul Rathbone. We will dedicate today’s space to this character. He was the great figure of the Cuban bourgeoisie.

Lobo was born in Venezuela and brought to Havana when he was barely a year old. His father began to work very young in what would later become the Bank of Venezuela. Thanks to his efforts and intelligence, he gradually rose to management of the company when he was only 22. One day he had the bad idea of denying a loan to Venezuelan dictator Cipriano Castro and ended up in jail. Released at last, after three months of confinement, he was evicted from Caracas.

In New York, where he settled, the North American Trust Company immediately offered him the position of administrator of their Havana branch. A company that soon became the National Bank of Cuba, but was neither national nor Cuban. It was already the year 1900.

His son Julio studied in the United States and graduated as an agricultural engineer. He returned to Cuba and, in 1920, undertook the general management of Galban, Lobo y Compañía –his father’s business—which was the beginning and launching pad of his sugar empire. He became one of the richest men in Cuba.

If as a family group, the Falla Bonet’s surpassed him, Lobo was above them as an individual owner. He came to own 16 sugar mills, 22 warehouses, a sugar brokerage firm, a radio communications agency, a bank, a shipping company, an airline, an insurance company and an oil company. He was the main seller of sugar on the world market.

In his book Los propietarios de Cuba [The Owners of Cuba], Guillermo Jiménez attributes to Lobo a personal fortune of $85 million, with assets estimated at one hundred million. Rathbone, his biographer, assures us in his book that if that fortune were measured in today’s dollars it would amount to no less than $5 billion.

However, in 1960, Lobo left Havana –he would say– with a small suitcase and a toothbrush. He settled in New York and continued in the sugar business, but never repeated his past exploits. When he died in 1983, his capital, Rathbone says, was estimated at $200,000. In fact, according to the biographer, very few of his generation prospered in exile.

Unlike the Falla Bonets who, when the Revolution triumphed, took no less than forty million dollars out of Cuba, Julio Lobo, a furious nationalist, continued to invest in the sugar industry and other companies, while continuing to expand his valuable art collection. After all, he knew he had always been smarter than his rivals… but that trust led him to take no precautions whatsoever.

He never wanted to intervene in politics, but he was a convinced opponent of Batista. He was a supporter of Batista’s removal, without caring who would succeed him.

In 1957 he gave 50,000 pesos to the “Accion Libertadora”, an anti-Batista organization, which in turn gave half of that money to the “26th of July Movement”. This led him to believe that he could make conditions on the Revolution.

Rathbone assures his readers that Ernesto Che Guevara showed him otherwise. He summoned him to his office. The guerrilla commander, who had become president of the National Bank of Cuba, told him that they had reviewed his accounts and that Che congratulated him for the efficiency of his companies, and for not owing a single penny to the Treasury, but he also told him that his assets would be intervened. He made him an offer: He could remain at the head of his sugar mills. In exchange, he would receive a salary from the State. Needless to say, Lobo refused. It was then that he packed his small suitcase.

Lobo’s purchase, in 1958, of the three mills owned by Hershey was very controversial. This was a very expensive transaction, because, already in exile outside Cuba, his creditors demanded payment of the outstanding debt for those mills that were no longer his.

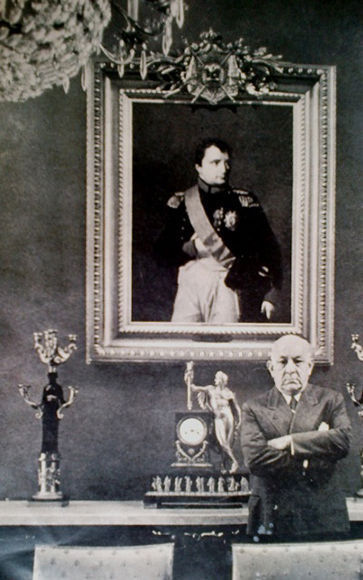

His specialized sugar library was the best and most complete in Cuba and perhaps in the whole world. His art gallery featured works by Da Vinci, Rafael, Miguel Ángel and Goya, among other great painters. His collection of incunabula and unique and rare books was famous.

He was obsessed with the personality of Napoleon and came to possess a large collection of relics and more than 200,000 documents, which he left in deposit to the nation and which are treasured today in the Napoleonic Museum in Havana.

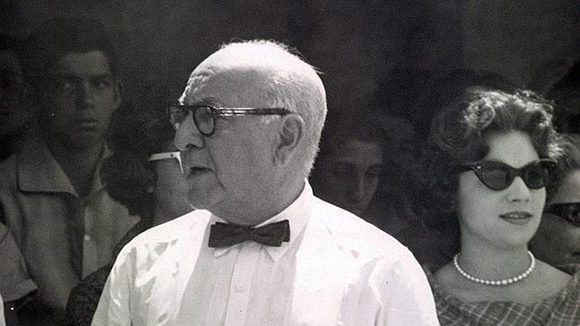

He was also interested in Hispanic-American subjects. Lobo was a Renaissance man, says Rathbone, extremely curious, with a deep knowledge of business, the subject of sugar, politics and history, and an impressive general culture.

He never had a yacht of his own and barely a social life. He was a compulsive worker, up to 16 hours a day. His hobby was gardening. He also had a penchant for collecting Hollywood actresses. He had a long relationship with Joan Fontaine and even proposed to Bette Davis. On one occasion he ordered that one of his swimming pools be filled with perfumed water to entertain the movie star and synchronized swimming diva Esther Williams.

He spent his final years caring for his first wife, whom he had divorced many years earlier. By then he could only move his eyes. He asked to be buried in a guayabera. A Cuban flag covered his coffin. That was his wish.

You must be logged in to post a comment.