Che Guevara 3

Che Guevara in Times of Pandemic

Che Guevara’s Gestures in Times of Pandemic

In these days when everyone shows the scars on their skin and in their consciousness, fruit of battles won and lost, I think that the gestures of Che are drawn in this Cuba that breaks the borders to accompany the people infected by the Coronavirus.

By Claudia Korol

March 22, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

He was not yet Che, when he traced a route of travel through the lepers of the continent. He wasn’t the romantic hero or the guerrilla. He was a sensitive doctor willing to “touch” human pain, a product of poverty, stigmatization, isolation, and fear.

In their journey across the continent together with Alberto Granado, they met and challenged the logic of health care, visiting the lepers from Cordoba to Peru and Brazil. They sought answers in their dialogues with the Peruvian doctor Hugo Pesce, who shared with them everything from the writings of José Carlos Mariátegui – the rebel communist who questioned dogmas and made passion a fundamental part of the revolution – to his knowledge of the daily fight against leprosy.

In those years Ernesto wrote to his father:

“[…] farewells like the one the sick people in the Lima Leper colony gave us are the kind of farewells that invite you to go on […] All the affection depends on our going there without our duster or gloves, shaking hands with them like any neighbor’s child and sitting among them to talk about anything or play soccer with them. It may seem to you like a pointless comradely, but the psychic benefit to one of these sick people treated like a wild animal, the fact that people treat them like normal beings is incalculable and the risk involved is extraordinarily remote […]’.

There are many other writings by the young Guevara, in which he expresses his conviction that there is no true medicine that does not “touch” the roots of pain, and that does not break those imposed conditions of isolation, when they do not build bridges in which collective solutions to urgent needs circulate back and forth. There is no social medicine that does not question the capitalism that enriches itself by sowing disease and multiplying misery.

Was the young Fuser (Furibundo Serna, as his friends called him) an irresponsible boy when he visited the lepers and treated the people who survived there without fear or prejudice?

Was Che irresponsible when he decided to join his fate, as José Martí said, to the poor of the earth, making his way in the guerrilla struggle?

Many tried to make him irresponsible, before and after his immense figure multiplied in the hearts of the people of the world. To those who did, he replied in his ironic style, in his farewell letter to his parents written in 1965: “Many will call me an adventurer, and I am one, only of a different kind and one of those who put their skins on to prove their truths.

Che put his skin, body and soul, to fight the virus of capitalism, because he knew that its expansion and multiplication would only lead to new and increasingly dangerous wars, invasions, dictatorships, epidemics, and social diseases. His generous seed was tattooed on the social consciousness of the people

In these days when everyone shows off the tracks on their skin and in their awareness, fruit of battles won and lost, I think that the gestures of Che are indicated in this Cuba. [The Cuba] that opens its borders to receive the people infected by the Covid-19 virus that arrived in the English ship. I think that they are in the Cuban doctors who travel to Brazil, after the Bolsonaro government violently expelled them, subjecting them to humiliation and persecution as criminals; in those who travel to Madrid, to Lombardy, and to other destinations where the threat multiplies. Wouldn’t they be “safer”, wouldn’t they feel more “cared for”, taking refuge on the island and closing its borders?

Here, the profound internationalism of those who feel / live the world as a territory is put to the test, in the face of the narrow nationalisms and localisms that raise walls, as if the viruses could not get over them.

I think that the traces of Che, his gestures, are in the many doctors, nurses, health workers, who are exposed to the risks of the body to body, but who demand, more than the applause, that an adequate budget is allocated for health, for a healthy diet, to guarantee proper hygiene in all the houses, to safeguard the minimum conditions of care in hospitals, wards, and in the slums where the ambulances do not arrive.

Is the budget not enough, they say? Let’s make the collective gift that our mother from Plaza de Mayo, Norita Cortiñas, asked us for her birthday, and let’s decide once and for all not to pay the foreign debt. What’s crazy? Yes, it could be. Mothers have always been crazy. Their madness is our mental health as a people, it’s memory against impunity.

Great crises. New answers needed. Something like demanding that the state stop police patrols from chasing us when we go out to meet a basic need, and that they allocate the means and resources to bring health and food to distant places. Water for the Wichi. Freedom for political prisoners. Care for those who survive in places of detention.

Demand from the state and at the same time, build autonomy. I think that the traces of Che are multiplying in the activists of the popular movements that today organize the arrival of food, of elements of hygiene, of attention and care for those who are in necessary isolation. Health guerrillas – including mental health guerrillas – are shaking hands with lepers, with those infected by fear, by shame, by hunger, by despair. Popular guerrillas of the embrace, of care, of intransigent rebellion against the state militarization of all dimensions of life.

I speak of the community feminists, the popular feminists, the lifeguards, building bridges from solitude to solitude. I speak of the women who take care of the picnic areas and soup kitchens, looking for ways to continue reaching those who survive every day with food. I speak of the multiplication of the memory of resistance, flooding and overflowing the social networks, so that the 30,000 know that here we are, as always, building squares in the houses if necessary, making history so that the revolutions do not fail. So that they know that neither yesterday nor today, we will leave them out in the open. That we will repeat the gestures, until no virus has a little crown. Until collective victory, against loneliness.

Epistolary of a Time

Epistolary of a Time:

Che Guevara Lived Through His Letters

By István Ojeda Bello

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

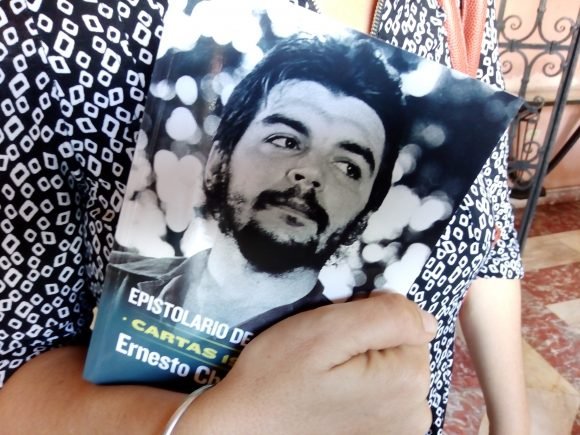

In the book Epistolario de un tiempo. Letters 1947-1967 Ernesto Guevara brings together Che’s most famous missives Photo: István Ojeda Bello/ Cubadebate.

For the first time, readers have in the same volume all the known letters of our Heroic Guerrilla, thanks to the joint effort of Ocean Sur Publishing House and Che Guevara Study Center with the Epistolary book of a time. Letters 1947-1967 Ernesto Guevara.

The text was presented this Friday at the Casa de la Amistad in Havana with the presence of relatives of the Argentinean-Cuban revolutionary fighter; and Fernando Rojas, Vice-Minister of Culture; Fernando González, Hero of the Republic of Cuba and president of the Cuban Institute of Friendship with the Peoples, as well as Adán Chávez Frías, ambassador of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela in our country.

In Epistolario de un tiempo… Che’s most famous missives converge, such as his farewells to the Cuban people and their children, along with another appreciable number of letters that denote his communication with figures of the politics, art and society of his time, such as Haydée Santamaría, Armando Hart, Celia Sánchez, Carlos Rafael Rodríguez, Regino G. Boti, Nicolás Guillén, Ernesto Sábato or Lisandro Otero, as well as his messages or reflections with institutions, media and ordinary citizens.

Many of these documents had remained unpublished until now, noted researcher Disamis Arcia Muñoz who along with Dr. Maria del Carmen Ariet Garcia was in charge of the compilation.

This book, he emphasized, helps to clarify controversial moments in the life of the Guerrilla of America as his discrepancies with other revolutionary fighters; but also to give a more intimate look to his conversations with close friends and even with strangers.

Arcia Muñoz stressed the importance of making known the epistle that Che sent to Fidel Castro on March 26, 1965. It, he affirmed, together with Socialism and Man in Cuba, and its inconclusive Critical Notes on Political Economy, completes the Guevara triad of thinking about the Cuban Revolution from its external projection, its technological development and the problems of socialist transition.

When reading several passages of the text, Aleida Guevara March noted that many of the realities described by her father can be appreciated in contemporary times. She also emphasized how, through the letters, we know this tender and paternal angle of a man who articulated sensitivity and sense of humor with a high sense of duty and self-criticism. “In this book you can find those things,” she concluded.

Presentación del libro Epistolario de un tiempo. Cartas 1947-1967 Ernesto Guevara. Foto: István Ojeda Bello/ Cubadebate.

Bolivia was the Moncada of Latin America

Rumi Perú

Bolivia was the Moncada of Latin America

By Zbigniew Marcin Kowalewski*

Translated and edited for CubaNews by Walter Lippmann.

“The initiative of the International Proletarian Army should not die in the face of the first failure,” Che Guevara wrote after his departure from the Congolese guerrillas. He reaffirmed it on the eve of his departure for the Bolivian guerrilla writing: “That a true proletarian internationalism be developed; with international proletarian armies, where the flag under which it fights is the sacred cause of the redemption of humanity. “

“Latin America will be one country”. This was the idea with which Che had come to fight in Bolivia and for which he sacrificed his life, as Guido “Inti” Peredo explained in his messages while working tenaciously to rebuild the National Liberation Army.

Fifty years after Che’s death, Pombo, a legendary Cuban survivor of this guerrilla, insists, with the same force of conviction and the same ardor: “It is the most important of all tasks: to achieve the union of all Latin American peoples,” because union is “the only way in which Latin American peoples can resist the aggression, influence, alienation to which imperialism submits.”

The historic and at the same time revolutionary value of the conversations of Maria del Carmen Garcés with today’s general Harry Villegas Tamayo is enormous. In the abundant literature on Che’s guerrilla, this book stands out for reviving with exceptional fidelity its political program, its deeds, its ideas, its spirit and – its respect! – its incredible morale.

One of the most striking things in this book is precisely the constant presence, in the life and action of the guerrilla, of the morale factor with its two aspects which, in Che’s words, “complement each other” – “a morale as to the ethical sense of the word and another in its heroic sense “- as a fundamental weapon of every true revolutionary movement.

Pombo, from Yara to Ñancahuazú, restores the truth against so many lies and so much petty discourse that they have accumulated distorting, dwarfing and trivializing the history of the Bolivian guerrilla.

“We do not always have to wait for all the conditions for revolution; the insurrectionary foco can create them.” This was another of Che’s fundamental ideas. How much had been said that the fate that the guerrilla ran in Bolivia denied and buried forever!

Harry Villegas and María del Carmen Garcés show that Bolivia had fully confirmed that it was a fair idea. The guerrillas contributed to creating conditions for the revolution by mobilizing and gaining the support of “a revolutionary force like that of the Bolivian miners, the most advanced of the continent.”

It was because of the fear that a miner’s uprising would be combined with the guerrilla action that the army perpetrated the San Juan massacre in the mines. “It was very unfeasible,” explains Pombo, that the single guerrilla group, with its own small force, could “catalyze and take advantage of this revolutionary situation” without counting on “the vanguard role that left parties should play.” But “within their conception of the mass struggle” they “could not play it,” notes Pombo. Che was right to comment at this political juncture: “It’s a pity not to have 100 more men.”

From Bolivia, within the framework of an incredibly bold strategy for the continental revolution, the internationalist guerrilla under his command had to contribute decisively to the development of the revolutionary movements in the Southern Cone and to coordinate or unify all these movements on a Latin American scale. By creating “two, three … many Vietnams” on an even wider plane -the tricontinental- it was possible to give the imperialist superpower an irreversible defeat.

In this strategy, the struggle for Latin America’s “unique, true and inalienable independence”, announced in the Second Declaration of Havana, was combined or interwoven with the socialist revolution, because for Che, there were “no more changes what to do: or socialist revolution or caricature of revolution. “

When Che and his fellow Cubans, Bolivians and Peruvians fought in Bolivia, the great majority of revolutionary movements and left-wing organizations from all Latin American countries met in Havana at the conference of Latin American Solidarity Organization (OLAS).

The Cuban delegation, explaining in its report that the objective was “to elaborate a common strategy to fight against Yankee imperialism and the oligarchies of bourgeois and landowners” and exposing the strategy of the continental revolution, he claimed “the Bolivarian ideology of conceiving Latin America as one and great Fatherland. “ Deepened by José Martí, “today the continental conception of a single Latin American people has been strengthened,” he said.

The Cuban delegation presented at the conference an “evident fact that has not been evaluated in all its dimension: never before has such a large group of people been known, with such a large population and a vast territory, cultures so similar, interests as similar and anti-imperialist purposes identical.

Each of us feels part of our America. We learned this from historical tradition; as our ancestors bequeathed to us, as our heroes taught us! None of these ideas is new to the representatives of the revolutionary organizations of Latin America. But have we sufficiently appreciated what these events represent?

Have we analyzed in depth what it means from as far back as the first years of the nineteenth century, and we had a continental idea of the struggle that was taking place throughout Latin America? Have we analyzed with sufficient clarity the irrefutable fact that Latin America constitutes one and great people? “

In July 1969, weeks before his capture and murder, Inti Peredo, faithful to the “Bolivarian dream and that of Che to politically and economically unite Latin America,” Che declared in his proclamation “We will return to the mountains! : “Our only and final goal is the liberation of Latin America, which is not only our continent, but also our homeland temporarily broken up into twenty republics.”

Pombo, from Yara to Ñancahuazú, collects today and again sends this message of Che, Inti, Coco, Chino, Tania, Moisés, Tuma, Joaquin, Ricardo, Rolando and all the other revolutionary fighters who fell in Bolivia. “To some extent,” says Harry Villegas, “Bolivia was the Moncada of America. Today we are seeing how crops are really being harvested from this blow that shook all of our America. “

Reading, studying, discussing and disseminating this book, in Latin America and in any other region of the world, is to politically, ideologically and morally rearm ourselves.

Warsaw, September 1, 2017

* Deputy editor-in-chief of the Polish edition of Le Monde Diplomatique and editor of Quaderni della Fondazione “Ernesto Che Guevara” edited in Italy

===========

LETTER FROM AUTHOR:

(Translation from Spanish. Original below)

Dear Walter,

Years ago we were in contact, we exchanged emails. The contact between us was an initiative of Celia [Hart].

From the very beginning (specifically since the reporting of [NY Times writer Herbert L.] Matthews) I followed the Cuban revolution and was politically formed largely under its influence. In 1967 I won an international contest by Radio Havana Cuba (they rewarded my essay Che’s Message to the Tricontinental) and I was invited to Cuba; It was my first trip. Worked on the guerrilla movements in Latin America, published a book on them in Poland (left in 1978). In the second half of the 1970s I spent four and a half years in Cuba, helping to train translators at the Pablo Lafargue Institute.

I was a leader of the Solidarność trade union (a member of the Lodz Regional Executive, then one of the most important industrial centers in Poland). The establishment of the state of war in December 1981 surprised me in France where I was traveling, so I spent the 1980’s in exile in France.

Then I came back and now I’m living in Poland. Since 1981 I have been a member of the Fourth [International]. Between 2005 and 2013 Militant in the Polish Labor Party (PPP), an almost purely labor party in its composition, created by a combative minority union that comes from a split from Solidarność and is called Free Trade Union “August ’80”. I was secretary for programmatic affairs of this party. The party was not maintained and in the long run and disappeared, while the union remains active.

At various stages of my life I tried to promote some work of solidarity with Cuba, although conditions there were never conducive. In People’s Poland there was no official work of solidarity, beyond a purely bureaucratic facade, and all unofficial political work provoked an intervention by the political police.

During the 1990s. There were very strong anti-Cuban bells here, both in the media and, indeed, in the State. Since the year 2000 I took a whole series of initiatives in this area, there was some development of a solidarity association, I was a member of its leadership, but the association disintegrated little by little. Then I had support from the Polish Labor Party for a job in Cuba, but finally, at the beginning of this decade, all work of solidarity with Cuba, which was already becoming smaller and more marginal, became extinct.

If you translate my text on the book of Maria Garces I will check it, evidently.

A hug

Zbigniew

Estimado Walter,

Hace anos estuvimos en contacto, intercambiamos mails. El contacto entre nosotros fue una iniciativa de Celia.

Desde el comienzo (concretamente desde el reportaje de Matthews) segui la revolución cubana y me forme politicamente en buena medida bajo su influencia. En 1967 gane un concurso internacional de Radio Habana Cuba (premiaron mi ensayo sobre el mensaje del Che a la Tricontinental) y fui invitado a Cuba; fue mi primer viaje. Trabaje sobre los movimientos guerrilleros en America Latina, publique en Polonia un libro sobre ellos (salió en 1978). En la segunda mitad de los 70 pase cuatro anos y medio en Cuba, formando traductores en el Instituto Pablo Lafargue.

Fui dirigente del sindicato Solidarność (miembro de la ejecutiva de la dirección regional de Lodz, entonces uno de los mas importantes centros industriales de Polonia). La instauración del estado de guerra en diciembre de 1981 me sorprendió en Francia donde me encontraba de viaje, asi que pase los anos 80 en exilio en Francia.

Luego volvi y estoy viviendo en Polonia. Desde 1981 soy miembro de la Cuarta. Entre 2005 y 2013 milite en el Partido Polaco del Trabajo (PPP), un partido casi puramente obrero en su composición, creado por un sindicato minoritario combativo que proviene de una escisión de Solidarność y se llama Sindicato Libre “Agosto ’80”. Fui secretario para asuntos programaticos de este partido. El partido no se mantuvo a la larga y desapareció, mientras que el sindicato sigue activo.

En varias etapas de mi vida intentaba promover algun trabajo de solidaridad con Cuba, aunque jamas habia condiciones propicias. En la Polonia Popular no habia ningun trabajo oficial de solidaridad, mas alla de una fachada puramente burocratica, y todo trabajo politico no oficial provocaba una intervención de la policia politica.

durante los anos 90. hubo aqui muy fuertes campanas anticubanas, tanto de los medios como, de hecho, del Estado. Desde el ano 2000 tome toda una serie de iniciativas en este terreno, hubo algun desarrollo de una asociación de solidaridad, fui miembro de su dirección, pero la asociación se desintegró poco a poco, Luego tuve apoyo del Partido Polaco del Trabajo para un trabajo Cuba, pero finalmente , a comienzos de esta decada, todo trabajo de solidaridad con Cuba, que ya era cada vez mas reducido y marginal, se extinguió.

Si traduces mi texto sobre el libro de Maria Garces lo verificare, evidentemente.

Un abrazo

Zbigniew

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

You must be logged in to post a comment.