Che Guevara’s Gestures in Times of Pandemic

In these days when everyone shows the scars on their skin and in their consciousness, fruit of battles won and lost, I think that the gestures of Che are drawn in this Cuba that breaks the borders to accompany the people infected by the Coronavirus.

By Claudia Korol

March 22, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

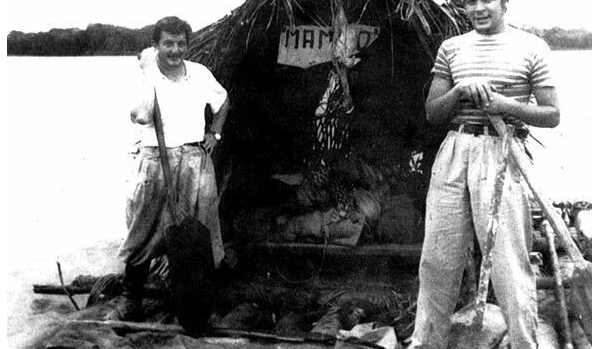

He was not yet Che, when he traced a route of travel through the lepers of the continent. He wasn’t the romantic hero or the guerrilla. He was a sensitive doctor willing to “touch” human pain, a product of poverty, stigmatization, isolation, and fear.

In their journey across the continent together with Alberto Granado, they met and challenged the logic of health care, visiting the lepers from Cordoba to Peru and Brazil. They sought answers in their dialogues with the Peruvian doctor Hugo Pesce, who shared with them everything from the writings of José Carlos Mariátegui – the rebel communist who questioned dogmas and made passion a fundamental part of the revolution – to his knowledge of the daily fight against leprosy.

In those years Ernesto wrote to his father:

“[…] farewells like the one the sick people in the Lima Leper colony gave us are the kind of farewells that invite you to go on […] All the affection depends on our going there without our duster or gloves, shaking hands with them like any neighbor’s child and sitting among them to talk about anything or play soccer with them. It may seem to you like a pointless comradely, but the psychic benefit to one of these sick people treated like a wild animal, the fact that people treat them like normal beings is incalculable and the risk involved is extraordinarily remote […]’.

There are many other writings by the young Guevara, in which he expresses his conviction that there is no true medicine that does not “touch” the roots of pain, and that does not break those imposed conditions of isolation, when they do not build bridges in which collective solutions to urgent needs circulate back and forth. There is no social medicine that does not question the capitalism that enriches itself by sowing disease and multiplying misery.

Was the young Fuser (Furibundo Serna, as his friends called him) an irresponsible boy when he visited the lepers and treated the people who survived there without fear or prejudice?

Was Che irresponsible when he decided to join his fate, as José Martí said, to the poor of the earth, making his way in the guerrilla struggle?

Many tried to make him irresponsible, before and after his immense figure multiplied in the hearts of the people of the world. To those who did, he replied in his ironic style, in his farewell letter to his parents written in 1965: “Many will call me an adventurer, and I am one, only of a different kind and one of those who put their skins on to prove their truths.

Che put his skin, body and soul, to fight the virus of capitalism, because he knew that its expansion and multiplication would only lead to new and increasingly dangerous wars, invasions, dictatorships, epidemics, and social diseases. His generous seed was tattooed on the social consciousness of the people

In these days when everyone shows off the tracks on their skin and in their awareness, fruit of battles won and lost, I think that the gestures of Che are indicated in this Cuba. [The Cuba] that opens its borders to receive the people infected by the Covid-19 virus that arrived in the English ship. I think that they are in the Cuban doctors who travel to Brazil, after the Bolsonaro government violently expelled them, subjecting them to humiliation and persecution as criminals; in those who travel to Madrid, to Lombardy, and to other destinations where the threat multiplies. Wouldn’t they be “safer”, wouldn’t they feel more “cared for”, taking refuge on the island and closing its borders?

Here, the profound internationalism of those who feel / live the world as a territory is put to the test, in the face of the narrow nationalisms and localisms that raise walls, as if the viruses could not get over them.

I think that the traces of Che, his gestures, are in the many doctors, nurses, health workers, who are exposed to the risks of the body to body, but who demand, more than the applause, that an adequate budget is allocated for health, for a healthy diet, to guarantee proper hygiene in all the houses, to safeguard the minimum conditions of care in hospitals, wards, and in the slums where the ambulances do not arrive.

Is the budget not enough, they say? Let’s make the collective gift that our mother from Plaza de Mayo, Norita Cortiñas, asked us for her birthday, and let’s decide once and for all not to pay the foreign debt. What’s crazy? Yes, it could be. Mothers have always been crazy. Their madness is our mental health as a people, it’s memory against impunity.

Great crises. New answers needed. Something like demanding that the state stop police patrols from chasing us when we go out to meet a basic need, and that they allocate the means and resources to bring health and food to distant places. Water for the Wichi. Freedom for political prisoners. Care for those who survive in places of detention.

Demand from the state and at the same time, build autonomy. I think that the traces of Che are multiplying in the activists of the popular movements that today organize the arrival of food, of elements of hygiene, of attention and care for those who are in necessary isolation. Health guerrillas – including mental health guerrillas – are shaking hands with lepers, with those infected by fear, by shame, by hunger, by despair. Popular guerrillas of the embrace, of care, of intransigent rebellion against the state militarization of all dimensions of life.

I speak of the community feminists, the popular feminists, the lifeguards, building bridges from solitude to solitude. I speak of the women who take care of the picnic areas and soup kitchens, looking for ways to continue reaching those who survive every day with food. I speak of the multiplication of the memory of resistance, flooding and overflowing the social networks, so that the 30,000 know that here we are, as always, building squares in the houses if necessary, making history so that the revolutions do not fail. So that they know that neither yesterday nor today, we will leave them out in the open. That we will repeat the gestures, until no virus has a little crown. Until collective victory, against loneliness.

You must be logged in to post a comment.