English Language Sources 24

What Elections Are About in Cuba

Ever Wonder What Elections Were About in Cuba?

If you haven’t bought the propaganda that there are no

elections in Cuba, I’m sure you have.

by Merri Ansara, February 16, 2018

It’s so interesting to be here during the time of nomination (January) and now consideration of the candidates for 6 weeks until the March 11 elections for National Assembly. While everyday life goes on seemingly unperturbed, there was a strong undercurrent of hopefulness and anticipation as the candidates were rolled out at the start of the month. This is the big one, the one where there will be a new president. More it is the first generational change in top leadership since the start of the Revolution.

A lot of hard work at all levels has gone into preparing for these elections over the past year or year and a half and the rollout was accompanied by a lot of fanfare.

There are a number of things the elections are not.

These are slate elections, not competitive elections. These are not party elections with varying platforms from which to choose. The Communist Party sets the direction and goals for the country and so voting the party up or down is not at play. Not all candidates for the National Assembly are in the Communist Party or even in the Communist Youth. As membership in the party is considered a badge of honor and merit rather than an affiliation (see below as to how people join the party), it is weighed among other criteria as the electoral commission tries to achieve a balance of representation of the existing society. A complicated concept for those of us with a different set if criteria.

(In Cuba, joining the party is a rigorous process of nomination, review, probation, and approval. Obviously, some bad apples slip through but it is considered a privilege and responsibility, not a bene to be in the party, not a right of position or privilege, and there are as many simple workers in the party as so-called elites).

There is no individual campaigning. The fact that these are block (slate) elections, of course, makes such competition unnecessary. You are voting up or down.

Here is what the elections are.

The first step in the national election process took place late January, as I said. 12,000 candidates were proposed in 970 meetings of the mass organizations — Cuban Central Trade Organization, Committees for Defense of the Revolution, The Cuban Women’s Federation, The National Small Farmers’ Association, the University Students Federation, and the High School Students Federation.

The Election Commision with subcommissions throughout the country at the provincial and local levels then sifted through the 12,000 visiting the institutions, organizations and work centers of the nominees as well as the neighborhoods in which they live, conducting interviews and collecting opinions and impressions. The goal was to ensure the proposal included 50 % municipal assembly representatives, members of civil society, candidates representative of the varying interests at the local, provincial and national level.

The findings then went district by district to the 168 Municipal Assemblies (12,515 local representatives who been voted in at the municipal level in the fall elections ) who then made the final nominations for their districts. All voters 16 or over in each district will be voting (up or down) for the candidates to represent their district in the National Assembly. Voting is not compulsory but usually is between 87 and 95%.

And if you think this sounds complicated, it sure seems so to me too and I hope I haven’t gotten any of it wrong. (You can see the Cubans national elections site on the web, with charts and graphs, www.cubaenelecciones.cu or at www.cubadebate.com)

So where have we ended up?

287 of the 605 candidates to National Assembly (47.4%) are currently local delegates to the municipal assemblies. Every district has at least two candidates, one of which is a local delegate.

338 of the nominees are first-time candidates

The average age is 49, with 80 candidates between 18 and 35 years of age.

53.2% of the candidates are women.

38% are considered Afro Cuban or mestizo.

The historic generation of the Revolution is well represented but 89.25% of candidates were born after the Revolution, that is after Jan 1, 1959.

Other than ensuring that every district has at least one delegate? The further breakdown on the election website mentioned previously is

28 are farmers or members of farming cooperatives

24 are in scientific and other kinds of research

12 are in sports

47 are in education

22 in the armed forces

4 are small private business entrepreneurs or self-employed

39 are local, provincial or national leaders of mass organizations (such as CDR, FMC)

11 are leaders of social or civic organizations

9 are student leaders

4 are members if religious organizations

46 are political body leaders

7 are judges or other members of the justice system

41 are members of the government, meaning ministers or similar kinds of posts

22 are members of fiscal, administrative and other types of bureaucratic offices

That may not add up to 605 as I may have missed some. You can go yourselves to www.eleccionesencuba.cu and see anything I’ve missed. For instance, I haven’t noticed who’re candidates from culture and the arts, and I won’t have a chance to sort that out before sending this.

So there is no campaigning as I think I said.

Still, as everyone is voting for candidates from their own district, if people have gone to any of the neighborhood meetings, or pay attention to sports, news, or television many of the candidates will be known.

Candidates have been posted in the newspapers with their pictures, age, occupation and organizational affiliations, and in special voting supplements. All candidates are also posted in multiple locations in the district where they are candidates, with the same information and alongside, a list of voters in that district (everyone over the age of 16). All candidates are also posted on television repeatedly throughout the day, province by province, 3 at a time.

The big question, of course, is who will be president. The president is elected by the new National Assembly once seated, so it will be April.

Speculation is rampant, centering not just on the so-called obvious successor, Vice President Diaz Canal but on two others in leadership, one in Havana and one in Santiago, both young and very well liked.

What we do know (we think) is that for the first time in Cuban history since the Revolution it won’t be a Castro. And it won’t be a member of what’s known as the historic generation.

It’s a very exciting time to be in Cuba. No one can be sure what’s ahead and while the country is moving ahead slowly along its chosen path, too slowly for many, moving ahead it is. Despite the local defeatists, cynics and naysayers one encounters, there’s still a sense of peace and stability rather than uncertainty and not either a sense of resignation. As a friend and strong supporter of the Revolution told me yesterday after a heated discussion with his 35-year-old son, “He told me, ‘look, Dad, we don’t agree on a lot of things but it’s still my country and my Revolution too. When push comes to shove, if anything happens you know I will be with you on the same side.'” Which he took to mean that even for the discontented youth, dignity, sovereignty, peace and well being are the paramount values and vision.

As I face going home to the cynical cartoon of government in Washington, the aftermath of another mass shooting in a school, and all the uncertainties we face on a daily basis, it’s a vision I wish I could look forward to too.

Merri

Havana February 16, 2018

As written with one finger on a phone, please excuse all typos. Please also excuse and feel free to forward verified corrections.

Please also forward to anyone you feel will be interested

The Cuba Embargo Needs To Go

Hillary Clinton: The Cuba Embargo

Needs To Go, Once And For All

July 31, 2015

In Miami today, Hillary Clinton forcefully expressed her support for normalization of U.S. relations with Cuba and formally called on Congress to lift the Cuba embargo. Hillary emphasized that she believes we need to increase American influence in Cuba, not reduce it — a strong contrast with Republican candidates who are stuck in the past, trying to return to the same failed Cold War-era isolationism that has only strengthened the Castro regime.

To those Republicans, her message was clear: “They have it backwards: Engagement is not a gift to the Castros – it’s a threat to the Castros. An American embassy in Havana isn’t a concession – it’s a beacon. Lifting the embargo doesn’t set back the advance of freedom – it advances freedom where it is most desperately needed.”

A full transcript of the remarks is included below:

“Thank you. Thank you very much. Thank you. I want to thank Dr. Frank Mora, director of the Kimberly Latin American and Caribbean Center and a professor here at FIU, and before that served with distinction at the Department of Defense. I want to recognize former Congressman Joe Garcia. Thank you Joe for being here – a long time friend and an exemplary educator. The President of Miami-Dade College, Eduardo Padrón and the President of FIU, Mark Rosenberg – I thank you all for being here. And for me it’s a delight to be here at Florida International University. You can feel the energy here. It’s a place where people of all backgrounds and walks of life work hard, do their part, and get ahead. That’s the promise of America that has drawn generations of immigrants to our shores, and it’s a reality right here at FIU.

“Today, as Frank said, I want to talk with you about a subject that has stirred passionate debate in this city and beyond for decades, but is now entering a crucial new phase. America’s approach to Cuba is at a crossroads, and the upcoming presidential election will determine whether we chart a new path forward or turn back to the old ways of the past. We must decide between engagement and embargo, between embracing fresh thinking and returning to Cold War deadlock. And the choices we make will have lasting consequences not just for more than 11 million Cubans, but also for American leadership across our hemisphere and around the world.

“I know that for many in this room and throughout the Cuban-American community, this debate is not an intellectual exercise – it is deeply personal.

“I teared up as Frank was talking about his mother—not able to mourn with her family, say goodbye to her brother. I’m so privileged to have a sister-in-law who is Cuban-American, who came to this country, like so many others as a child and has chartered her way with a spirit of determination and success.

“I think about all those who were sent as children to live with strangers during the Peter Pan airlift, for families who arrived here during the Mariel boatlift with only the clothes on their backs, for sons and daughters who could not bury their parents back home, for all who have suffered and waited and longed for change to come to the land, “where palm trees grow.” And, yes, for a rising generation eager to build a new and better future.

“Many of you have your own stories and memories that shape your feelings about the way forward. Like Miriam Leiva, one of the founders of the Ladies in White, who is with us today – brave Cuban women who have defied the Castro regime and demanded dignity and reform. We are honored to have her here today and I’d like to ask her, please raise your hand. Thank you.

“I wish every Cuban back in Cuba could spend a day walking around Miami and see what you have built here, how you have turned this city into a dynamic global city. How you have succeeded as entrepreneurs and civic leaders. It would not take them long to start demanding similar opportunities and achieving similar success back in Cuba.

“I understand the skepticism in this community about any policy of engagement toward Cuba. As many of you know, I’ve been skeptical too. But you’ve been promised progress for fifty years. And we can’t wait any longer for a failed policy to bear fruit. We have to seize this moment. We have to now support change on an island where it is desperately needed.

“I did not come to this position lightly. I well remember what happened to previous attempts at engagement. In the 1990s, Castro responded to quiet diplomacy by shooting down the unarmed Brothers to the Rescue plane out of the sky. And with their deaths in mind, I supported the Helms-Burton Act to tighten the embargo.

“Twenty years later, the regime’s human rights abuses continue: imprisoning dissidents, cracking down on free expression and the Internet, beating and harassing the courageous Ladies in White, refusing a credible investigation into the death of Oswaldo Paya. Anyone who thinks we can trust this regime hasn’t learned the lessons of history.

“But as Secretary of State, it became clear to me that our policy of isolating Cuba was strengthening the Castros’ grip on power rather than weakening it – and harming our broader efforts to restore American leadership across the hemisphere. The Castros were able to blame all of the island’s woes on the U.S. embargo, distracting from the regime’s failures and delaying their day of reckoning with the Cuban people. We were unintentionally helping the regime keep Cuba a closed and controlled society rather than working to open it up to positive outside influences the way we did so effectively with the old Soviet bloc and elsewhere.

“So in 2009, we tried something new. The Obama administration made it easier for Cuban Americans to visit and send money to family on the island. No one expected miracles, but it was a first step toward exposing the Cuban people to new ideas, values, and perspectives.

“I remember seeing a CNN report that summer about a Cuban father living and working in the United States who hadn’t seen his baby boy back home for a year-and-a-half because of travel restrictions. Our reforms made it possible for that father and son finally to reunite. It was just one story, just one family, but it felt like the start of something important.

“In 2011, we further loosened restrictions on cash remittances sent back to Cuba and we opened the way for more Americans – clergy, students and teachers, community leaders – to visit and engage directly with the Cuban people. They brought with them new hope and support for struggling families, aspiring entrepreneurs, and brave civil society activists. Small businesses started opening. Cell phones proliferated. Slowly, Cubans were getting a taste of a different future.

“I then became convinced that building stronger ties between Cubans and Americans could be the best way to promote political and economic change on the island. So by the end of my term as Secretary, I recommended to the President that we end the failed embargo and double down on a strategy of engagement that would strip the Castro regime of its excuses and force it to grapple with the demands and aspirations of the Cuban people. Instead of keeping change out, as it has for decades, the regime would have to figure out how to adapt to a rapidly transforming society.

“What’s more, it would open exciting new business opportunities for American companies, farmers, and entrepreneurs – especially for the Cuban-American community. That’s my definition of a win-win.

“Now I know some critics of this approach point to other countries that remain authoritarian despite decades of diplomatic and economic engagement. And yes it’s true that political change will not come quickly or easily to Cuba. But look around the world at many of the countries that have made the transition from autocracy to democracy – from Eastern Europe to East Asia to Latin America. Engagement is not a silver bullet, but again and again we see that it is more likely to hasten change, not hold it back.

“The future for Cuba is not foreordained. But there is good reason to believe that once it gets going, this dynamic will be especially powerful on an island just 90 miles from the largest economy in the world. Just 90 miles away from one and a half million Cuban-Americans whose success provides a compelling advertisement for the benefits of democracy and an open society.

“So I have supported President Obama and Secretary Kerry as they’ve advanced this strategy. They’ve taken historic steps forward – re-establishing diplomatic relations, reopening our embassy in Havana, expanding opportunities further for travel and commerce, calling on Congress to finally drop the embargo.

“That last step about the embargo is crucial, because without dropping it, this progress could falter.

“We have arrived at a decisive moment. The Cuban people have waited long enough for progress to come. Even many Republicans on Capitol Hill are starting to recognize the urgency of moving forward. It’s time for their leaders to either get on board or get out of the way. The Cuba embargo needs to go, once and for all. We should replace it with a smarter approach that empowers Cuban businesses, Cuban civil society, and the Cuban-American community to spur progress and keep pressure on the regime.

“Today I am calling on Speaker Boehner and Senator McConnell to step up and answer the pleas of the Cuban people. By large majorities, they want a closer relationship with America.

“They want to buy our goods, read our books, surf our web, and learn from our people. They want to bring their country into the 21st century. That is the road toward democracy and dignity and we should walk it together.

“We can’t go back to a failed policy that limits Cuban-Americans’ ability to travel and support family and friends. We can’t block American businesses that could help free enterprise take root in Cuban soil – or stop American religious groups and academics and activists from establishing contacts and partnerships on the ground.

“If we go backward, no one will benefit more than the hardliners in Havana. In fact, there may be no stronger argument for engagement than the fact that Cuba’s hardliners are so opposed to it. They don’t want strong connections with the United States. They don’t want Cuban-Americans traveling to the island. They don’t want American students and clergy and NGO activists interacting with the Cuban people. That is the last thing they want. So that’s precisely why we need to do it.

“Unfortunately, most of the Republican candidates for President would play right into the hard-liners’ hands. They would reverse the progress we have made and cut the Cuban people off from direct contact with the Cuban-American community and the free-market capitalism and democracy that you embody. That would be a strategic error for the United States and a tragedy for the millions of Cubans who yearn for closer ties.

“They have it backwards: Engagement is not a gift to the Castros – it’s a threat to the Castros. An American embassy in Havana isn’t a concession – it’s a beacon. Lifting the embargo doesn’t set back the advance of freedom – it advances freedom where it is most desperately needed.

“Fundamentally, most Republican candidates still view Cuba – and Latin America more broadly – through an outdated Cold War lens. Instead of opportunities to be seized, they see only threats to be feared. They refuse to learn the lessons of the past or pay attention to what’s worked and what hasn’t. For them, ideology trumps evidence. And so they remain incapable of moving us forward.

“As President, I would increase American influence in Cuba, rather than reduce it. I would work with Congress to lift the embargo and I would also pursue additional steps.

“First, we should help more Americans go to Cuba. If Congress won’t act to do this, I would use executive authority to make it easier for more Americans to visit the island to support private business and engage with the Cuban people.

“Second, I would use our new presence and connections to more effectively support human rights and civil society in Cuba. I believe that as our influence expands among the Cuban people, our diplomacy can help carve out political space on the island in a way we never could before.

“We will follow the lead of Pope Francis, who will carry a powerful message of empowerment when he visits Cuba in September. I would direct U.S. diplomats to make it a priority to build relationships with more Cubans, especially those starting businesses and pushing boundaries. Advocates for women’s rights and workers’ rights. Environmental activists. Artists. Bloggers. The more relationships we build, the better.

“We should be under no illusions that the regime will end its repressive ways any time soon, as its continued use of short-term detentions demonstrates. So we have to redouble our efforts to stand up for the rights of reformers and political prisoners, including maintaining sanctions on specific human-rights violators. We should maintain restrictions on the flow of arms to the regime – and work to restrict access to the tools of repression while expanding access to tools of dissent and free expression.

“We should make it clear, as I did as Secretary of State, that the “freedom to connect” is a basic human right, and therefore do more to extend that freedom to more and more Cubans – particularly young people.

“Third, and this is directly related, we should focus on expanding communications and commercial links to and among the Cuban people. Just five percent of Cubans have access to the open Internet today. We want more American companies pursuing joint ventures to build networks that will open the free flow of information – and empower everyday Cubans to make their voices heard. We want Cubans to have access to more phones, more computers, more satellite televisions. We want more American airplanes and ferries and cargo ships arriving every day. I’m told that Airbnb is already getting started. Companies like Google and Twitter are exploring opportunities as well.

“It will be essential that American and international companies entering the Cuban market act responsibly, hold themselves to high standards, use their influence to push for reforms. I would convene and connect U.S. business leaders from many fields to advance this strategy, and I will look to the Cuban-American community to continue leading the way. No one is better positioned to bring expertise, resources, and vision to this effort – and no one understands better how transformative this can be.

“We will also keep pressing for a just settlement on expropriated property. And we will let Raul explain to his people why he wants to prevent American investment in bicycle repair shops, in restaurants, in barbershops, and Internet cafes. Let him try to put up barriers to American technology and innovation that his people crave.

“Finally, we need to use our leadership across the Americas to mobilize more support for Cubans and their aspirations. Just as the United States needed a new approach to Cuba, the region does as well.

“Latin American countries and leaders have run out of excuses for not standing up for the fundamental freedoms of the Cuban people. No more brushing things under the rug. No more apologizing. It is time for them to step up. Not insignificantly, new regional cooperation on Cuba will also open other opportunities for the United States across Latin America.

“For years, our unpopular policy towards Cuba held back our influence and leadership. Frankly, it was an albatross around our necks. We were isolated in our opposition to opening up the island. Summit meetings were consumed by the same old debates. Regional spoilers like Venezuela took advantage of the disagreements to advance their own agendas and undermine the United States. Now we have the chance for a fresh start in the Americas.

“Strategically, this is a big deal. Too often, we look east, we look west, but we don’t look south. And no region in the world is more important to our long-term prosperity and security than Latin America. And no region in the world is better positioned to emerge as a new force for global peace and progress.

“Many Republicans seem to think of Latin America still as a land of crime and coups rather than a place where free markets and free people are thriving. They’ve got it wrong. Latin America is now home to vibrant democracies, expanding middle classes, abundant energy supplies, and a combined GDP of more than $4 trillion.

“Our economies, communities, and even our families are deeply entwined. And I see our increasing interdependence as a comparative advantage to be embraced. The United States needs to build on what I call the “power of proximity.” It’s not just geography – it’s common values, common culture, common heritage. It’s shared interests that could power a new era of partnership and prosperity. Closer ties across Latin America will help our economy at home and strengthen our hand around the world, especially in the Asia-Pacific. There is enormous potential for cooperation on clean energy and combatting climate change.

“And much work to be done together to take on the persistent challenges in our hemisphere, from crime to drugs to poverty, and to stand in defense of our shared values against regimes like that in Venezuela. So the United States needs to lead in the Latin America. And if we don’t, make no mistake, others will. China is eager to extend its influence. Strong, principled American leadership is the only answer. That was my approach as Secretary of State and will be my priority as President.

“Now it is often said that every election is about the future. But this time, I feel it even more powerfully. Americans have worked so hard to climb out of the hole we found ourselves in with the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression in 2008. Families took second jobs and second shifts. They found a way to make it work. And now, thankfully, our economy is growing again.

“Slowly but surely we also repaired America’s tarnished reputation. We strengthened old alliances and started new partnerships. We got back to the time-tested values that made our country a beacon of hope and opportunity and freedom for the entire world. We learned to lead in new ways for a complex and changing age. And America is safer and stronger as a result.

“We cannot afford to let out-of-touch, out-of-date partisan ideas and candidates rip away all the progress we’ve made. We can’t go back to cowboy diplomacy and reckless war-mongering. We can’t go back to a go-it-alone foreign policy that views American boots on the ground as a first choice rather than as a last resort. We have paid too high a price in lives, power, and prestige to make those same mistakes again. Instead we need a foreign policy for the future with creative, confident leadership that harnesses all of America’s strength, smarts, and values. I believe the future holds far more opportunities than threats if we shape global events rather than reacting to them and being shaped by them. That is what I will do as President, starting right here in our own hemisphere.

“I’m running to build an America for tomorrow, not yesterday. For the struggling, the striving, and the successful. For the young entrepreneur in Little Havana who dreams of expanding to Old Havana. For the grandmother who never lost hope of seeing freedom come to the homeland she left so long ago. For the families who are separated. For all those who have built new lives in a new land. I’m running for everyone who’s ever been knocked down, but refused to be knocked out. I am running for you and I want to work with you to be your partner to build the kind of future that will once again not only make Cuban-Americas successful here in our country, but give Cubans in Cuba the same chance to live up to their own potential.

Thank you all very, very much.”

###

For Immediate Release, July 31, 2015

Contact: press@hillaryclinton.com

PAID FOR BY HILLARY FOR AMERICA

Contributions or gifts to Hillary for America are not tax deductible.

Hillary for America, PO Box 5256, New York

Cuban media coverage, an example:

Hillary Clinton Calls in Miami for Lifting of U.S. blockade on Cuba

HAVANA, Cuba, Aug 1 (acn) Democrat pre-candidate to the 2016 presidential elections in the United States, Hillary Clinton, asked Congress on Friday, from Miami, Florida, to lift the economic, commercial and financial blockade imposed on Cuba since 1962, the Prensa Latina news agency reported.

In a speech at the International University of Florida, the former Secretary of State asked lawmakers to take advantage of this decisive moment, after the resumption of diplomatic relations between the two countries and the reopening of embassies in the respective capitals on July 20.

The U.S. policy towards Cuba is at a crossroads and next year’s elections by the White House will determine whether we will carry on with a new course in this regard or return to the old ways of the past, she added.

We must decide between commitment and sanctions, between adopting new thinking and returning to the deadlock we were during the Cold War, she pointed out.

She added that even many Republicans on Capitol Hill are beginning to recognize the urgency of continuing onward to dismantle the sanctions and this is the moment when their leaders must join this task or get out of the way of those who carry on.

Clinton added that the blockade must end once and for all; we must replace it with “more intelligent measures that manage to consolidate the interests of the United States,” and called the red party leadership on Capitol Hill to join this policy.

The former Secretary of State reiterated her support for the policy of rapprochement with the island that began after December 17, when Cuban President Raul Castro and his U.S. counterpart, Barack Obama, announced the decision of reestablishing diplomatic relations.

For years, the state of Florida was the base of a strong opposition to bonds with Havana, which made the blockade an untouchable issue among those who aspired to be elected for posts in that territory, especially for Republicans.

On several occasions, the former first lady has defended the lifting of the blockade against the Caribbean nation, particularly in her book Hard Choices, in which she assures that while she was Secretary of State (2009-2013) she recommended Obama to review the policy towards Cuba.

A survey conducted last week by the Pew Research Center showed that 72 percent of U.S. citizens are in favor of lifting the blockade against Cuba and 73 percent approve Obama’s decision of reestablishing diplomatic relations with the Caribbean island.

A survey by the McClatchy newspaper chain and the Marist Institute for Public Opinion released on Friday showed that 44 percent of likely voters prefer Clinton; 29 percent Republican Jeb Bush; and 20 percent controversial aspirant Donald Trump, for the November 2016 elections.

“Los adultos se están comportando como niños.”

HARPER’S BAZAAR

“Los adultos se están comportando como niños.”

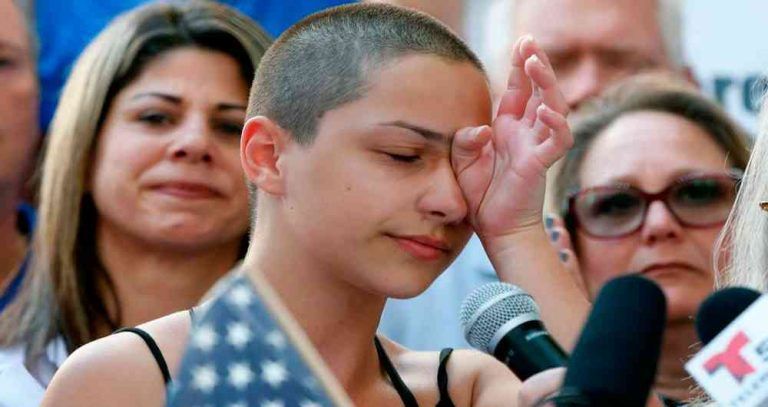

Emma González, estudiante de Parkland, se sincera sobre su lucha por el control de armas

By Emma González

26 de febrero 2018

Una traducción de CubaNews. Editado por Walter Lippmann.

Mi nombre es Emma González. Tengo 18 años, soy cubana y bisexual. Me siento tan indecisa que no logro decidir cuál es mi color favorito, y soy alérgica a 12 cosas. Sé dibujar, pintar, hacer croché, coser, bordar—cualquier cosa productiva que pueda hacer con mis manos mientras veo Netflix.

Pero ya nada de esto importa.

Lo que importa es que la mayoría de los estadounidenses se han vuelto autocomplacientes frente a toda la injusticia sin sentido que ocurre a su alrededor. Lo que importa es que la mayoría de los políticos estadounidenses se han dejado dominar más por el dinero que por las personas que votaron por ellos. Lo que importa es que mis amigos están muertos, al igual que cientos y cientos que también han muerto en todo Estados Unidos.

Mi nombre es Emma González. Tengo 18 años, soy cubana y bisexual. Me siento tan indecisa que no logro decidir cuál es mi color favorito, y soy alérgica a 12 cosas. Sé dibujar, pintar, hacer croché, coser, bordar—cualquier cosa productiva que pueda hacer con mis manos mientras veo Netflix.

Pero ya nada de esto importa.

Lo que importa es que la mayoría de los estadounidenses se han vuelto autocomplacientes frente a toda la injusticia sin sentido que ocurre a su alrededor. Lo que importa es que la mayoría de los políticos estadounidenses se han dejado dominar más por el dinero que por las personas que votaron por ellos. Lo que importa es que mis amigos están muertos, al igual que cientos y cientos que también han muerto en todo Estados Unidos.

En resumidas cuentas, no queremos que a las personas les quiten sus armas. Sólo queremos que las personas sean más responsables. Queremos que los civiles tengan que hacer muchos más trámites para obtener lo que quieren, porque si esos trámites pueden impedirle tener un arma a quienes no deberían tenerla, entonces nuestro gobierno habrá hecho algo bien. Todo cuanto queremos es regresar a la escuela. Pero queremos saber que cuando entremos allí no tendremos que preocuparnos por la posibilidad de vernos frente al cañón de un arma. Queremos arreglar este problema para que no vuelva a ocurrir, pero sobre todo queremos que la gente se olvide de nosotros cuando todo esto acabe. Queremos regresar a nuestras vidas y vivirlas al máximo por respeto a los muertos.

Los maestros no necesitan tener armas para proteger a sus alumnos, lo que necesitan es una sólida educación para enseñar a sus alumnos. Eso es lo único que debería aparecer en la descripción de su trabajo. La gente dice que los detectores de metales ayudarían. Que le digan eso a los niños que ya tienen detectores de metales en su escuela y siguen siendo víctimas de la violencia armada. Si quieren ayudar, armen las escuelas con material escolar, libros, terapeutas, cosas que realmente necesitan y pueden utilizar.

Una cosa más. Queremos más atención psicológica para quienes la necesitan—incluyendo a los hombres furiosos y frustrados que casi siempre cometen estos crímenes. Las enfermedades mentales y la violencia armada no guardan relación directa, pero cuando marchan juntas, hay estadounidenses—a menudo niños—que pierden la vida. No necesitamos las excusas de la ANR, necesitamos que la ANR finalmente se ponga de pie y utilice su poder para darle al pueblo de Estados Unidos algo que merezcan. (Y por favor, fíjense que cuando los miembros del movimiento Marcha por Nuestras Vidas hablan de la ANR, nos referimos a la organización como tal, no a sus miembros. Muchos de esos miembros comprenden y apoyan nuestra lucha por una posesión de armas responsable, a pesar de que la organización impide que se aprueben leyes sobre armas que tengan sentido en nombre de la protección de la segunda enmienda—en vez de proteger al pueblo de Estados Unidos.)

Así que marche con nosotros el 24 de marzo. Regístrese para votar. Acuda de verdad a las urnas. Porque necesitamos, de una vez y por todas, despojar a la ANR de sus argumentos.

Emma Gonzalez dice, “¡Mentira!”

CNN

Emma Gonzalez, estudiante de la Florida, le dice a los legisladores y defensores de las armas: “¡Mentira!”

26 de febrero 2018. Traducido por CubaNews. Editado por Walter Lippmann.

(CNN) Emma Gonzalez, estudiante de último año en la Secundaria Marjory Stoneman Douglas, habló en una concentración pro-control de armas el sábado en Fort Lauderdale, Florida, días después de que un hombre armado entró en su escuela en la cercana Parkland y mató a 17 personas.

Lea a continuación la transcripción completa de su discurso:

Ya tuvimos un momento de silencio en la Cámara de Representantes, así que me gustaría que tuviéramos otro. Gracias.

Cada una de las personas reunidas aquí hoy, todas estas personas, deberían estar en casa guardando luto. Pero en vez de eso, estamos juntos aquí, porque si lo único que nuestro gobierno y nuestro Presidente pueden hacer es transmitirnos sus pensamientos y plegarias, entonces es hora de que las víctimas sean el cambio que necesitamos ver. Desde los tiempos de nuestros Próceres y desde que agregaron la 2da Enmienda a la Constitución, nuestras armas se han desarrollado a una velocidad que me da vértigo. Las armas han cambiado, pero nuestras leyes no.

Claro que no entendemos por qué debería ser más difícil planificar un fin de semana con los amigos que comprar un arma automática o semi-automática. Para comprar un arma en la Florida no se requiere un permiso ni una licencia de armas, y una vez que se compra no es necesario registrarla. No se necesita un permiso para portar un rifle o una escopeta ocultos. Usted puede comprar tantas armas como desee de una vez.

Hoy leí algo que me resultó muy impactante. Y lo fue desde el punto de vista de un maestro. Cito: ‘Cuando los adultos me dicen que tengo derecho a poseer un arma, todo lo que escucho es que mi derecho a poseer un arma tiene más peso que el derecho de sus alumnos a vivir. Todo lo que escucho es mi, mi, mi…’.

En vez de preocuparnos por nuestro examen del capítulo 16 de AP Gov, tenemos que estudiar nuestras notas para garantizar que nuestros argumentos basados en política e historia política sean irrebatibles. Los estudiantes de esta escuela sentimos que hemos estados debatiendo sobre armas durante toda nuestra vida. Sobre AP Gov ha habido unos tres debates este año. Incluso algunos análisis sobre este tema tuvieron lugar durante el tiroteo, mientras los estudiantes se escondían en los armarios. Sentimos que los que ahora estamos involucrados, los que estaban allí, los que envían mensajes, los que escriben en Twitter, los que hacen entrevistas y hablan con la gente, están siendo escuchados por primera vez sobre esta tema, que sólo en los últimos cuatro años ha surgido más de 1,000 veces.

Hoy descubrí un sitio web llamado shootingtracker.com. Nada en el título sugiere que está rastreando solamente los tiroteos en Estados Unidos, pero, ¿necesita abordar eso? Porque Australia tuvo un tiroteo masivo en 1999 in Port Arthur (y después de la) masacre introdujo mecanismos de seguridad contra las armas, y desde entonces no ha tenido ni un tiroteo más. Japón nunca ha tenido un tiroteo masivo. Canadá ha tenido tres y el Reino Unido tuvo uno, y ambos países decretaron leyes para el control de armas, y sin embargo aquí estamos, con sitios web dedicados a informar estas tragedias para que se puedan registrar en estadísticas para su conveniencia.

Esta mañana vi una entrevista y noté que una de las preguntas fue, ‘¿Cree usted que sus hijos tendrán que participar en otros ejercicios de preparación contra tiroteos en la escuela?’ Y nuestra respuesta es que nuestros vecinos no tendrán que hacerlo más. Cuando le hayamos dado nuestra opinión al gobierno – y quizás los adultos se han acostumbrado a decir ‘Así son las cosas,’ pero si nosotros los estudiantes hemos aprendido algo, es que, si no estudiamos, suspendemos. Y en este caso, si uno no hace nada activamente, otras personas terminarán muertas, así que es hora de empezar a hacer algo.

Nosotros seremos los niños sobre los que usted leerá en los libros de texto. No porque vayamos a ser otro dato estadístico sobre tiroteos masivos en Estados Unidos, sino porque, como dijo David, vamos a ser el último tiroteo masivo. Al igual que en [el caso] Tinker v. Des Moines, vamos a cambiar las leyes. Eso va a ser Marjory Stoneman Douglas en ese libro de texto, y va a deberse a la acción incansable de los directores, los maestros, los familiares y la mayoría de los estudiantes. Los estudiantes que murieron, los que todavía están en el hospital, los que ahora sufren de TEPT, los que tuvieron ataques de pánico durante la vigilia porque los helicópteros no nos dejaban tranquilos, volando sobre la escuela las 24 horas del día.

Hay un tweet sobre el que quisiera llamar la atención. Tantas señales de que el tirador de la Florida tenía problemas mentales, incluso había sido expulsado por su conducta indebida e imprevisible. Sus vecinos y compañeros de clase sabían que tenía grandes problemas. Siempre hay que informar estos casos a las autoridades una y otra vez. Y lo hicimos, una y otra vez. Nadie que lo conoció desde que empezó la secundaria se sorprendió al escuchar que él fue quien disparó. A quienes dicen que no debimos haberlo aislado, ustedes no conocieron a este niño. Está bien, lo hicimos. Sabemos que ahora están alegando problemas de salud mental, y yo no soy psicóloga, pero tenemos que prestar atención al hecho de que esto no fue sólo una cuestión de salud mental. Él no hubiera dañado a tantos estudiantes con un cuchillo.

¿Y si dejamos de culpar a las víctimas por algo que fue culpa del estudiante, culpa de quienes para empezar lo dejaron comprar las armas, quienes organizan festivales de armas, quienes lo alentaron a comprar accesorios para sus armas para hacerlas totalmente automáticas, quienes no se las quitaron cuando supieron que él manifestó tendencias homicidas? Y no estoy hablando del FBI, sino de las personas que vivían con él. Estoy hablando de los vecinos que lo veían con armas fuera de la casa.

Si el Presidente quiere venir y decirme en mi cara que fue una terrible tragedia que nunca debió haber sucedido y sigue diciéndonos que no se va a hacer nada al respecto, voy a preguntarle alegremente cuánto dinero recibió de la Asociación Nacional del Rifle.

¿Quieren saber una cosa? No importa, porque ya yo lo sé. Treinta millones de dólares. Divididos por el número de víctimas de armas de fuego en Estados Unidos sólo en el primer mes o mes y medio de 2018, la cifra da $5,800. ¿Eso es lo que estas personas valen para ti, Trump? Si no haces algo para que esto no vuelva a ocurrir, aumentará el número de víctimas de armas de fuego y se reducirá la cantidad de lo que valen. Y no tendremos ningún valor para ti.

Le decimos a cada político que acepta donaciones de la ANR, vergüenza debía darte.

A los cánticos de multitudes, vergüenza debía darles.

Si su dinero estaba tan amenazado como nosotros, ¿su primer pensamiento sería ‘cómo esto se va a reflejar en mi campaña?, ¿a cuál debo escoger?’ ¿O nos escogerían a nosotros, y si respondieron que a nosotros, ¿lo demostrarán de una vez? ¿Saben cuál sería una buena manera de demostrarlo? Tengo un ejemplo de cómo no demostrarlo. Hace un año, en febrero de 2017, el Presidente Trump revocó una regulación de la era de Obama que hubiera facilitado impedir la venta de armas de fuego a personas con ciertas enfermedades mentales.

A partir de mis interacciones con el tirador antes del tiroteo y de lo que ahora sé sobre él, realmente no creo que era un enfermo mental. Esto lo escribí antes de saber lo que dijo Delaney. Delaney dijo que se le había diagnosticado [una enfermedad mental]. Yo no necesito a un psicólogo ni necesito ser psicóloga para saber que revocar aquella regulación fue una idea realmente estúpida.

El Senador republicano Chuck Grassley de Iowa fue el único patrocinador del proyecto de ley que le impide al FBI verificar los antecedentes de personas declaradas como enfermos mentales, y ahora está diciendo oficialmente, ‘Bueno, es una pena que el FBI no verifique los antecedentes de estos enfermos mentales.’ ¡No me digas! Esa oportunidad la eliminaste el año pasado.

La gente del gobierno por quienes votamos para estar en el poder nos está mintiendo. Y parece que nosotros los niños somos los únicos que nos damos cuenta, y nuestros padres […unintelligible…]. A las compañías que hoy tratan de caricaturizar a los adolescentes diciendo que todos somos egocéntricos y tenemos obsesión con la moda, que nos someten mandándonos a callar cuando nuestro mensaje no llega a los oídos de la nación, estamos preparados para decirles, ¡mentira! A los políticos del Congreso y el Senado que se sientan en sus butacas doradas financiadas por la ANR y nos dicen que no se pudo haber hecho nada para evitar esto, les decimos ¡mentira! A quienes dicen que tener leyes más rígidas sobre control de armas no reduce la violencia de las armas, le decimos ¡mentira! A quienes dicen que una persona buena con un arma impide detiene a una persona mala con un arma, le decimos ¡mentira! A quienes dicen que las armas son sólo herramientas como cuchillos y tan peligrosas como los automóviles, le decimos ¡mentira! A quienes dicen que ninguna ley pudo haber evitado los centenares de tragedias sin sentido que han ocurrido, le decimos ¡mentira! A quienes dicen que nosotros los niños no sabemos de qué estamos hablando, que somos demasiado jóvenes para entender cómo funciona el gobierno, le decimos ¡mentira!

Si están de acuerdo, regístrense para votar. Contacten a sus congresistas locales. Díganle cuatro verdades.

(Cánticos de multitud) Sáquenlos de aquí.

Video:

https://www.cnn.com/2018/02/17/us/florida-student-emma-gonzalez-speech/index.html

Jack Shepherd: Statement to NRC

Statement to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission

on the Licensing of Units 2 and 3 at San Onofre, California

By Jack A. Shepherd, early 1980s. exact date unknown

I am presently involuntarily retired from the American Bridge Division of the U.S. Steel Corporation because its Maywood plant was closed in March, 1980. During the last ten years of the thirty seven that I worked for this company, one of my duties as an Inspector, was to radiograph welds to ascertain that they were of acceptable quality. I have been a member of organized labor since 1938, and I am now an Honorary member of the United Steelworkers of America. I am an active participant in the Labor Safe Energy and Full Employment Committee.

While I have not heard all of the testimony that has been presented in this hearing to date, I believe that this Commission should know that a sizable and growing section of the American labor movement does not support the use and proliferation of nuclear power. In general our opposition to nukes is based on three factors: 1 The excessive risks to the safety and health of the workers in the plants and to the public living in their vicinity. 2 The fact that nuclear power provides fewer jobs than any of the alternative sources of power that are available. 3 The high cost of nuclear power in comparison to other alternative power sources.

I don’t believe that I could add anything to the ample testimony that has already been submitted about the danger that the use of nuclear power creates in the San Onofre57rtf area. The inability to evacuate the area in a reasonable length of time in the event of an accident; the possibility of a major earthquake in the area; the evidence of an increase in the level of radiation that has already occurred due to the operation of Unit 1 are valid arguments against licensing Units 2 and 3.

To the best of my knowledge, the testimony that has been presented in these proceedings by union members has been in favor of licensing Units 2 and 3. It has come from Brothers who are employed at the San Onofre facility. One of these workers seemed to feel that the opponents of licensing were questioning his ability as a welder to produce the quality of work which nuclear powered generators require. Prior to my employment at American Bridge, I worked as a High Pressure Pipe Welder in refinery construction. Like my Brother welder, I also took pride in my ability as a craftsman to perform my duties. However, even if all the welds and the other work was perfect, it would not resolve problems such as public evacuation, earthquake danger or so-called “low-level radiation” in the plant and the San Onofre area.

I will not take the time in this hearing that would be required to discuss nuclear power from a union point of view, but members of the Labor Safe Energy and Full Employment Committee would welcome-such a discussion with other union members if it could be arranged. We believe this issue deserves far more discussion and consideration in the labor movement than it has received in the past.

Based on the training I received before radiographing welds, I think that the one thing you can say about radiation is: the less of it you get, the better off you are. Radiation exists as a natural part of our environment. If man possessed the technology, it would be logical, in my judgment, to try to lessen or even eliminate the natural level of radiation. Conversely, it is illogical to engage in anything that raises this level of radiation in the environment.

Nuclear power produces low-level radiation from its beginning to its end. Workers are radiated when it is mined. The ore tailings, once they are brought to the surface, inject more radiation into the environment than when they were buried in the earth. Workers in industries where radio-active materials are used receive increased radiation. So do workers who transport it. The end product of nuclear use is radio-active waste. There are tens of thousands of tons of this radio-active junk around right now, and nobody has come up with a trully safe way of disposing of it. In my opinion, even if the possibility of a nuclear melt-down did not exist, the foregoing facts constitute sufficient reason to stop the use of nuclear power.

When I see the problem of low-level radiation casually dismissed, as nuclear power advocates are wont to do, I am reminded of the fable about the race between the tortise and the hare. Like low-level radiation, the tortise just kept grinding away while rabbit slept, and we all know that he won. But the prize in a race where low-level radiation is a competitor, is not something anyone wants to win because it consists of medical problems and the possibility of untimely death.

At American Bridge, the level of radiation which workers outside the radiation area received, was held to one half the legal limit when this work was done. Most of the radiography was done after midnight when there were no other workers present. We had some wild cats in the plant which the workers fed. Two of them were accidentally radiated. It is not a pleasant sight to see any living thing die from excessive radiation.

With the sole exception of hydro-power, nuclear power provides fewer jobs than any other type of electric generation. Nukes employ a large number of workers during the time of their construction, but from then on, the work force is very small. Other methods of power generation not only employ more workers, but they create jobs for coal miners, oil workers and transport workers.

In this period of growing unemployment, I and other unionists are concerned about the availability of work. While the curtailment of nuclear power in the short haul could reduce the number of jobs in construction, in the long haul, they would also gain. Unemployed workers are not apt to be customers for the goods and services that they normally consume. This, of course, would include electricity. If there is a contraction in the use of electricity, there will be fewer construction jobs because new power plants will not be needed.

Nuclear power is not only the most unsafe form of energy, it is also the most costly. When the cost of a nuclear plant is amortized thru the years of its productive use, it is the most expensive means of producing electricity.

Testimony has already been introduced which shows that Southern California Edison has placed 40% of its total investment in nuclear and, power,/in so-doing, has only increased its generating capacity by 12%.This testimony has not been refuted at any time that I have been at these hearings. While I am on this subject of costs, I would like to present some further evidence. It comes from the states of Utah and Washington.

Utah Power and Light, to my knowledge, is the only utility company in the nation which generates all of its power with coal. Recently, it reported a 92% increase in profits for the second quarter of this year. Contrast this with Consolidated Edison, which is soliciting government help and trying to pass rate increases to its customers, to avoid bankruptcy because of Three Mile Island.

The Washington Public Power Supply System is also in serious financial trouble because of nuclear power. The estimated cost of the five nukes this outfit is building has risen from four billion to twenty four billion dollars. Two of these nukes have been placed on hold, and the company is considering drastic rate increases. They are also asking the Bonneville’ Power Administration, a federal energy-distributing agency, to raise its rates to help pay the cost of completing the other three nukes.

All things considered, coal generated power would appear to be the most satisfactory way to meet the general criteria which a sound union energy program would embrace. It is safe. The technology exists to burn it environmentally clean. It is cheap. It exists in such ample supply in the nation that it could supply our energy needs until new and better sources are developed. It would create more jobs than any’., other energy source, that is immediately available. It is now being brought into the Los Angeles harbor in huge amounts for shipment to Japan.

Nuclear supporters cited the extensive use of nukes in Russia as proof of its safety. However, it is well documented, that since 1970, when nukes proliferated, there has been a steady increase in the death rate of children – particularly under the age of one year.. in Russia.

Implementing Our Trade Union Policy and Recruitment

Implementing Our Trade Union Policy and Recruitment

by Jack Shepherd, Los Angeles branch, July 10, 1981

Socialist Workers Party Discussion, Vol. 37, No. 24, July 1981

==========================

Thanks to David Walters, at Holt Labor Library, for the scanned version, which has been OCRed and edited for reposting here by Walter Lippmann and Kimberly Sloss. Please let me know if you find any typos. This essay is just under 5000 words.

Walter Lippmann.

walterlx@earthlink.net

==========================

walterlx@earthlink.net

==========================

The party’s resolutions, while analyzing and portraying the political reality and the relationship of class forces at given conjunctures in time, stresses the more favorable variant in the further evolution of the class struggle. Generally this approach has been characterized as “the right to revolutionary optimism.” It is something I have always supported in our movement, and it has been my observation that those who questioned this proposition were embarking on a path that led out of the party.

Even as I had been a firm supporter of the party’s decisions to follow the radicalization in peripheral struggles such as the anti-war, civil rights, women’s and gay movements, I supported the party’s turn to industry. This support was motivated by the opinion that the economy had entered a deeper and more intractable crisis than any which had occurred since World War II. It was not based upon the concept that the workers had miraculously shed the effects of the preceding thirty years which had nurtured and sustained the generally conservative mood which shaped their thinking.

Making a turn in the party is not an easy thing. I listened to reports and assessments, which in my judgment, were overly optimistic, but were also a necessary part of carrying out the turn. Optimism has been, and always will be a legitimate part of our party and I want to affirm my support to Ito continued use. .

The party has reached the stage in our turn to the industrial workers where any fears that we are going to be left on the sidelines when they go into action should be allayed. I think the time has come when we can realistically assess the level of radicalization in the unions and build the party in the process.

We should continue the party’s present trade union policy

I am a supporter of the party’s trade union policy. I believe that the flanking tactic with respect to the trade union leadership is, soundly conceived, that the open socialist policy, within, the limits of what is possible, is correct, and that we should continue to concentrate our work in the unions around the social and political issues. It follows that I think Comrade Weinstein and his co-thinkers are mistaken.

I have always been loath to judge the application of any party policy from afar. I believe you have to have all the details and facts before a sound judgment can be made. Truth manifests itself in the concrete. The reports from Lockheed in Marietta, Georgia, and from Newport News should have clarified any misunderstandings about how our trade union policy was carried out in those situations.

It is a fact of life that any trade union policy will always result in some casualties. Sometimes it is because it is ineptly applied. In such instances, the leadership, as it has been doing, must intervene and educate against these misapplications. Sometimes the bosses take off on a tangent as is the case with Lockheed. In these situations, we are required to mount a counter-attack using every available means to win. The outcome of such a fight also shapes the application of our trade union-policy, The only tirade union policy which might not have called us to Lockheed’s attention, in my judgment, would have been to just work and do nothing.

Taking union posts has not helped other radical parties

The policy of taking union posts and concentrating on union issues is not the panacea that some comrades believe. This is basically what the other radicals have been-doing. A look at some of their 4 experiences should be instructive.

The first of these experiences involves the Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist). They were in a caucus which won some posts, including the presidency, in the Ford Motor plant in Pico Rivera, California. From the time they took, office, they were in a fight with a right-wing majority on the executive board, which enjoyed the support of the UAW Regional Director. This red-baiting fight was so intense that the majority of the members would not even take a .union leaflet when it was passed out at the plant gates.

After the plant closed, the president was put on trial for allegedly using the phone for unauthorized calls. At the trial, he said that he didn’t care what the verdict was, because he was going into the construction business. He was found guilty.

The CP (ML) has lost many of its members. It is in a political crisis over Maoism. It also has organizational problems. It is in a major internal discussion to decide whether it should continue as a party or dissolve.

The second experience involves the Communist Labor Party in the Bethlehem Steel plant in Huntington Park, California. The CLP ran candidates for union offices with mixed results. They lost the presidency to Wilfred Anderson, but they won some griever posts. Had they been more successful, they could have very easily found themselves in the same situation that prevailed at Ford because the local has a right-wing majority on its executive board.

This plant is first on a list of plants which Bethlehem is considering closing. Anderson, who is basically a good unionist, is trying to keep the plant open by cooperating with the company. He says that if he pushes grievances the way he used to, the plant will fold in 60 days.

The CLP is critical of Anderson, and will probably run against him in 1983 if the plant is still open. Basically this is a no-win situation. The CLP advocates a policy that is a little more militant, but they agree with Anderson that the plant is on the verge of being closed. Having gone through the experience of a plant closure myself, the last thing I would recommend would be to take union office to administer the procedure.

The CLP operates out of a front group called Californians Against Taft-Hartley (14b). I was trapped into attending one of its meetings because a co-worker who was riding with me wanted to go: In the past, these meetings attracted more than thirty. This particular meeting was down to eight or nine. The discussion was about what could be done to keep the committee functioning. Like other radical parties, the CLP has lost members and is now down to its hard-core cadre.

The third experience involves the Communist Workers Party. I recently had an opportunity to listen to a report on the union struggle at NASSCO by Rodney Johnson. The wages at this shipyard are about $2.00 per hour less than the rates paid by the industry on the West Coast, and the safety conditions are very poor. Military expenditures sustain the expectations of NASSCO workers that they will have contracts. The CWP and their friends ran for office and were elected. They combined militancy with democratic worker mobilizations to press for resolution of the many problems, particularly around safety, which existed. The company retaliated against one of these in-plant demonstrations that took place at lunch hour in conjunction with a ship launching, by discharging a large number of the union’s officers and shop stewards. The workers established picket lines and closed the shipyard. The strike was ended on the basis that the discharges would be given expedited arbitration. Twenty-seven cases are involved. The Ironworkers International put the local in receivership. The authorities put Boyd, Loo and Johnson on trial for allegedly conspiring to blow up the shipyard’s electrical facilities. They have been found guilty, and the verdict is being appealed. The CWP and their supporters are also petitioning to decertify the Ironworkers Union at NASSCO and replace it with an independent union.

While a final balance sheet must be delayed until the outcome of the arbitrations, the court appeal and the decertification election is known, I believe it is safe to say that we would not like to see any of our comrades in a similar situation. Johnson reported that the CWP and its friends still retain the support of a large Section of the NASSCO workers, but the obstacles to be overcome are formidable. The answer may well be that worker militancy must exist in many locals before it can be translated into victories in any of them.

Of course, all of the experiences I relate are in California. Perhaps it is different in other parts of the country. If there is some place where radicals, or for that matter even militants, are winning victories and recruiting, it would be a valid argument for adopting a more interventionist trade union policy.

Our trade union policy now and during World War II

Of all previous party, trade union policies, the present one is closest to our trade union policy during World War II. At that time we refrained from taking union posts and devoted our efforts to socialist propaganda work, Minneapolis Trial support and general union educational propaganda around the no-strike pledge, etc. We characterized this union position as “a policy of caution.” I might add that, in my judgment, this cautious policy served us well. It laid the groundwork for our extensive intervention into union leadership and the post-World War II struggles of the industrial workers.

The present union policy puts a little more stress on the open socialist approach, but I can recall selling about 40 Militant subscriptions not too long after I had completed my probationary period. Our abstention from taking positions of union leadership was based on the proposition that the wildcat strikes, which occurred in greater numbers as the war went on, could not be led to victories. The combination of the government, the companies and the union bureaucrats, plus the political support which most workers gave the war, led to assorted strikes and victimizations of the strike leaders.

Of course, John L. Lewis scored a major victory when the UMWA struck during World War II. But that was an action sanctioned by the International leadership of a major union and not a wildcat strike led by radicals or militants.

The success of the UMWA strike was powerful testimony in support of our trade union analysis. We were the only section of the labor movement that propagated the idea that the unions had to withdraw the no-strike pledge in order to resolve the accumulating problems of their members. Towards the end of the war the idea began to spread. At its last war-time convention, the UAW debated a resolution to withdraw the no-strike pledge. It lost by a handful of votes. However, it was not until the war was coming to an end and it was apparent that the working class was getting ready to go into action that were able to recruit these workers.

The economy and capital mobility has the workers on the defensive

Although it is masked to a certain extent by the inflation, the situation today is one in which the deflationary forces in the economy are coming more and more to the fore. The days when workers were fighting for reverse seniority in order to take extended vacations while they were collecting unemployment and supplementary unemployment benefits are behind us.

Since 1929, the last time these deflationary forces were unleashed, the ruling class has developed a powerful new weapon – capital mobility. During the years 1969-1976, 15 million jobs in the United States were wiped out by plant and department closures. The trend has escalated since then, and while I don’t have figures, I think it is safe to say that almost 25% of the U.S. workforce has lost jobs due to closures.

Most of these job losses were not due to business failures, but rather to capital mobility. Most of the capital migration within the U.S. has been from the Frostbelt to the Sunbelt and from unionized areas to non-union areas. But all areas of the U.S. have been affected by capital migration overseas. As a matter of fact, the rate of plant-closures in the South has been greater than in the U.S. as a whole. During the 1969-76 period, more than one third of the plants in the South, employing 100 or more workers, were closed, primarily due to capital migration overseas.

Because of their ability to freely move capital, the bosses, in many instances, have been relieved from the task of making frontal assaults on the unions to drive down wages and working conditions. To date, nobody has come up with a strategy that workers can employ on the economic front to stop these closures. At the prompt time, the choice for workers appears to be: 1) Refuse a wage cut, remain militant and go down with the flags flying like the workers did in the Gary, Indiana, American Bridge plant; or 2) Make concessions, go home and pray and probably go out with a whimper like they appear;, to be doing at the Bethlehem Steel plant in Huntington Park.

In 1950, the U.S. multinationals had $11 billion invested overseas. By 1974, it had grown to $118 billion. While I don’t have figures on what U.S. overseas investments are now,. we can rest assured that the amount has expanded since the trend to overseas investment has increased, in the last seven years.

Plant closures and the threat of plant closures are exerting enormous pressure on the unions and the workers. Ford, for- example, recently asked the UAW to open its contract before its termination date so that the company could share in the concessions that were being given to Chrysler. When its request was refused, Ford said: We are now building a world car. We can close all of our U.S. plants and still produce as many cars as we can expect to sell:

Perhaps someone may believe that you can confront problems like this one facing the Ford workers by taking a griever position and being militant on the assembly line. I don’t. The only answer I see is a long-range one. It requires the radicalization and politicalization of the workers. And this type of educational work can best be done without the burden of a griever job.

Any serious worker fightback must be political

As I have already noted, nobody has come up with any strategy, on the union level to stop these closures. Nor have they been able to use the closure of a particular plant to speed worker radicalization. This is something we should try to initiate if the opportunity presents itself, or be prepared to assist if it is initiated by someone else.

The right to invest, disinvest and move capital throughout the capitalist sector of the world is assured to the ruling class by their control over the political process. Both the Republican and Democrat parties are supporters of “free enterprise,” the economic system which makes the aforementioned rights possible. Any political party which would challenge these rights or start dismantling the structure upon which they rest would have to be anti-business, anti-free enterprise and anti-capitalist. A labor party, or any other party, would be as helpless as a baby in terms of arresting the ruling class assault on the living standards of the workers if it didn’t possess some of the foregoing ingredients. A return to a Democrat administration would be unlikely to provide the union leaders or the workers with any of the relief that they hope to obtain.

The ability of capital to move overseas was won in World War II and formalized at Bretton Woods. But it also rests on a number of subsequent government decisions such as: 1) Government insurance to compensate U.S. companies if their investments are lost through nationalizations by foreign governments; (This law may, have expired, but it existed for decades.) 2) Favorable tariff rulings; 3) IRS rulings which exonerate overseas profits from being taxed in the year they were made and taxes them in the year they are repatriated to the U.S.

Can anyone imagine any capitalist party tampering with the structure which presently facilitates overseas capital flight? Yet this is exactly what would be required if a political party was going to help Ford workers in their pending negotiations.

Domestic capital mobility also rests on a political base such as: 1) Publicly financed incentives and tax breaks to encourage investment in a particular city, county or state; 2) Low accident, disability and unemployment benefits for workers in some states; 3) Right-to-work laws which inhibit unionization.

The unions have been trying for years to solve some of the problems that encourage domestic capital migration through the Democratic Party. In a period of economic uncertainty, are the Democrats apt to pass laws which correct these inequities?

Under free enterprise, the right to invest or disinvest in a way that maximizes profits in the most sacred of all rights. Many of the plants that have been closed were profitable. But workers need jobs. Communities should have the to a decent environment rather than being converted into slums as the effects of the economic dislocated ripples through their economies.

A capitalist politician, in the name of corporate responsibility, might ask a company not to close a plant. But what if the company refuses? Is he or she going to enact legislation that says worker and community rights must be given pre-eminence over the right to maximize profits?

Most of the workers that I have talked to during the last twenty years –even those who went through the great depression– were of the opinion that it could never happen again. What is happening now is contrary to everything that they had been led to expect. Many still have hopes that things will get better. Some even, think Reagan will deliver on his promises in a reasonable period of time. We believe that the economic downturn is in its preliminary stages. If we are correct, the next period will be one in which the working class begins to dispel its misconceptions and illusions. It will begin to deepen and expand its radicalization into more meaningful and broader areas. We can do our work best as open socialists unencumbered by union posts and responsibilities, We also must be patient and confident. Time is on our side.

Where the union leadership is going now

In a recent issue of the western edition of Steelabor, the official publication of the United Steelworkers of America, the front page featured a quotation from Woody Guthrie, and its back page carried an interview with a Polish steelworker who was representing Solidarity at an AFL-CIO meeting. I have read this paper for nearly forty years. Not so long ago, If I were a betting man, I could have gotten odds of more than 100 to 1 that there never would be a Steelabor with a format that was this radical. As a matter of fact, I don’t think I would have been willing to bet a dollar on it.

Some comrades have expressed the opinion that radicalism of this type by the union leadership reflects pressure from the ranks below. I think they are mistaken.

The first time I encountered this kind of radicalism emanating from the union leadership was shortly after the enactment of the Taft-Hartley law. I believe it was in 1948.

During about a six-months period, the leadership published rearms of material showing that the U.S. was really run by a handful of the super-rich, etc. I don’t know what they did in other locals, but we were in the leadership of my local. We saw to it that it was passed out to the membership. It was just about the time that we were beginning to get a response from rank and file members that this anti-capitalist propaganda offensive stopped.

Then, as now, the union leaders were of the opinion that they were facing a major crisis. Nor was it a figment of their imaginations. If the Taft-Hartley law had been enforced with the same conservative, anti-labor vindictiveness with which it was passed, the unions would have been in a struggle to survive. Of course, we know this didn’t happen. The union leadership established a detente with the bosses, and class conciliation continued to prevail in government circles. Through the years, however, this conciliation shifted more to the side of the bosses, and it returns were more meager for labor.

Reagan’s election, the increased number of union-hating conservatives in Congress and in the state legislatures, plus the economic crisis, have again convinced the union leaders that they are in jeopardy. That is why they have mounted another radical propaganda offensive. It is a good thing. We should use it for all it’s worth and for as long as it lasts. But again, I repeat, we should not interpret this leadership radicalism as a reflection of wide-spread radicalization in the ranks of the union membership.

The union leaders are ready to make another deal

On the other hand, the union leadership is exploring the possibilities of another deal. Kirkland establishes a committee to meet with Reagan administration officials to set what can be worked out. The July 7th Wall Street Journal reports that the Steelworker leadership is opening negotiations with the steel industry to decide if the no-strike agreement will be extended to cover the 1983 negotiations. The industry wants the terms of the no-strike agreement watered down because “past settlements were too costly.” This policy of union cooperation with the steel industry was justified to the workers, after the 1959 strike, as a way to save jobs. At that time, I believe, there were more than 400,000 workers covered by the Basic Steel agreement. The WSJ says that 286,000 are covered now.

As has already been noted in this internal discussion the union leaders are seeking to solve the problems of their members by increasing their cooperation with the industrialists. We can be sure that the price the bosses are willing to pay for this cooperation will be less and less acceptable to the workers. But this is a part of the learning process which the workers have to go through before they will be ready to strike out in a new direction. It is conceivable, even likely, that this worker dissatisfaction will take some time before it manifests itself in action unless the bosses’ terms are so bad that the union leaders are forced to call a strike.

Radicalization in other social sectors will outpace industrial workers

Meanwhile, the Reagan program is devastating the many other sections of our society in the here and now. In the next immediate period, the radicalization of these affected sectors, in my judgment, will outpace the radicalization in the ranks of the industrial workers.

These other sectors don’t have the same social weight or significance of the industrial workers, but we should not underestimate the importance of their radicalization. In fact, this radicalization, if transmitted into the unions, can accelerate the radicalization of the industrial workers. And we have an almost perfect opening to start this operation.

The September 19 coalitions

As a result of their left turn, the union leaders are anxious to be seen with Black leaders, environmentalists, etc., who they formerly shunned. They want all the help they can get if Reagan and his union-hating cohorts come down on them, and they want to influence and rebuild the Democratic Party. They have set September 19 as a day of national mobilization against the Reagan program in Washington, D.C. and in major cities across the country.

In Los Angeles, the September 19th coalition is called the Greater Los Angeles-Labor Community Coalition. It is open to all union locals, AFL-CIO or independent, any community organizations, other coalitions and political parties that are opposed to all or any part of the Reagan program. As they put it: “Any group that is capable of fogging up a mirror in the morning is eligible to join and have one representative at coalition meetings.”

I have been representing the Coalition Against Plant Closures, September 19th coalition meetings are held in the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor, AFL-CIO office, and they are usually attended by about 25 people. More are involved, but sometimes they miss meetings. A representative of the New American Movement usually attends, so the coalition, is clearly open to any radical party that wants to participate.

To date, one expanded coalition meeting has been held. I suggested that we should invite a representative of the hunger-striking Vietnam veterans to this expanded meeting. While some coalition members expressed reservations, the vote was favorable, and a veteran did speak. The expanded meeting was attended by about 175.