What is behind the US decision to process visas for Cubans in Colombia?

What is behind the US decision to process visas for Cubans in Colombia?

October 26, 2017

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Why Colombia? Learn about it in the lines that follow. Photo taken from Somos Colombianos.

The US decision. to process immigrant visas for Cubans in Colombia is a maneuver that hides perverse purposes, which can be understood in the treatment of this issue by the US government.

Some elements:

The State Department, on its official website, says that, “At this moment it, is being determined when the interviews will begin to be scheduled.” However, they themselves, in one of the sections of their site, locate a link to an article by Martí News that quoting a spokesman, says “Cubans must obtain a visa from Colombia and be willing to stay” a few weeks “in the country to complete the process that would allow them to emigrate to the United States,” later this same media disinformation on 10/20/17 states, “the Consular Section official Virgil Carstens informed that the first appointments for visas will not be available” until November 2017 “, repeating that Cubans” should plan the stay of at least a few weeks in Colombia, “adding that if additional administrative processing is necessary, they may” go out and return at a later date to near the end of the process “.

It is noteworthy that this little serious and unreliable middle is the one selected by the State Department to give the first of this news, the answer is that they are interested in moving these messages and others linked to this subject to the Cuban community based in Miami, to influence it and through it in those of the island to condition their states of opinion in their favor.

The objectives of the maneuver:

- Create internal instability appearing before the public opinion to be oblivious to the problems that supposedly may arise.

- To present Cuba as guilty of the obstacles and delays that Cuban families must face for reunification.

- Moving the image of a US worried about fulfilling its international commitments, in this case the one of granting a minimum of 20 thousand visas of emigrants to the year.

Internal destabilization

In Colombia they have certain consular capacities, but the Colombian embassy in Cuba may not have them to process an unexpected volume of visas, this creates the first obstacle and can generate crowds of people in the surroundings of this seat with the usual inconveniences and the possible occurrence of incidents , a situation that would serve to strengthen the opinion matrix of an environment of insecurity around diplomatic personnel accredited in the country.

With the sharp decrease in the number of visas for migrants and the obstacles to obtaining them that will necessarily arise, the intention is to increase the internal pressure of those who wish to emigrate, in order to create destabilizing situations that may lead to a considerable increase in illegal exits to the US, and lead to a mass exodus. In addition, Cuba, guilty of the problem.

The New York Times , “It has been hard ‘: Cuban families in limbo before the suspension of US visas,” states that, “the United States by interrupting the flow of immigration from the island by reducing its staff at the embassy of La Havana, in response to the mysterious attacks could trigger a further increase in migration, particularly if Cuba is experiencing an economic recession. Citing Vicki Huddleston, ex-head of the then SINA in the period 1999 to 2002, says that there is a risk of another massive migration.

The analysis of the medium reinforces the opinion matrix of Cuban responsibility, placing the US action. as a response and unveils America’s vision of where the situation they are trying to lead could get to, while preparing the public opinion of their country for it.

The mention of a presumed incidence of an economic recession in the evolution of events, is not done lightly, it they want to push us toward it damaging one of our main routes of income of foreigners that is the tourism. For that reason, the warning against trips to Cuba , the appearance of alleged tourists affected and the involvement of Canadian citizens, a country that is among the main sources of tourists to Cuba.

No criticism is a skillful journalistic treatment of the subject.

What could the US response be? before a massive exodus?

According to what was published by the Coast Guard , they would decree the naval blockade to prevent vessels from Florida reaching Cuba and picking up potential migrants, while intercepting those coming from our country, returning them to their origin, this would increase the destabilization of the country.

It is also known that the Miami right dream of a situation of this type to try to use it to pressure the US government to intervene in Cuba.

Some additional questions:

Why Colombia?

The docility of the politicians of that country to the Yankee requirements is no secret. It is enough to remember its acceptance of the establishment of seven US military bases on its territory and its alignment with Washington against Venezuela among other acts of vassalage. These are the reasons which guaranteed the acceptance and collaboration of the Colombian government, without having to resort to pressures that could transcend public opinion, jeopardizing the objectives of this new assembly.

Will all migrant visa applicants have the financial capacity to cover the cost of lodging and meals for a few weeks in Colombia?

Most likely and the Americans know it is not.

What are you pursuing with this?

What they want is that, given the impossibility of covering their expenses in Colombia and those that may lead them to leave, they will be forced to seek alternative sources of income, some may, according to their personal characteristics, be linked to crime, others could obtain low-income jobs and the more they would begin to seek help from the Colombian and US governments, this could lead to a complex situation in Colombia with which they would mediately accuse Cuba of not clarifying the “attacks and forcing the “philanthropical” US to try to help Cubans through an alternative solution.

Faced with this situation, it is expected that they will press for agreements to be returned, seeking to increase the number of those who would be frustrated with their hopes to emigrate to the United States. by legal means, those who, along with those who will dismiss the Colombia route as unviable, could, according to their assessments, bring about a mass exodus as we have already analyzed..

But Cuba knows its enemy.

(Taken from PostCuba )

Bush Father Accused of Sexual Abuse

US Actress Accuses Bush Father of Sexual Abuse

October 26, 2017

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

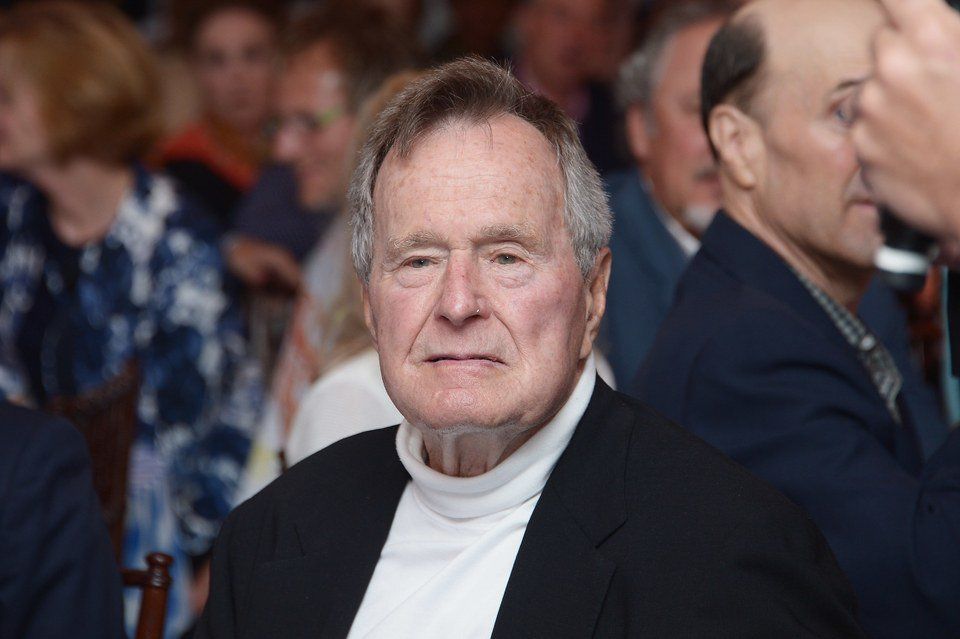

This is the second accusation that implicates George Bush Sr. Photo: @kim_ugh.

Local sources reported today that New York actress Jordana Grolnick denounced George HW Bush , who ruled the United States from 1989-1993, for sexual harassment.

The woman recounted an episode similar to that of the first accuser, Heather Lind, who on Wednesday filed a complaint through her Instagram account, which she erased shortly thereafter.

According to Grolnick, Bush grabbed her buttocks in August of last year during a group photo shoot at the Ogunquit Playhouse in Maine.

The actress told the Deadspin news site that Bush joked that her favorite magician is “David Cop-a-Feel” – a wordplay on the name of the character David Copperfield and the English word “feel” – and he fingered her.

He added that his wife, Barbara Bush, responded, “She’s going to have him sent to jail.”

“We were all around him and his wife Barbara for a picture,” recalled Grolnick, who was currently working on a production of “Hunchback of Notre Dame” at the Maine Theater. “I was next to him and he put his hand on my back.”

On Wednesday, the former president apologized publicly to actress Heather Lind, who accused him of having tampered with her while the president was in a wheelchair.

The former president’s office said in a statement that he often repeats the same joke” and sometimes he has patted women on the butt in a jocular tone.”

He apologizes “to all the people he has offended,” the official statement added.

Bush, 93, was charged first by Heather Lind, 34, in her Instagram account, in a message he later decided to delete.

“When I had the opportunity to meet George Bush four years ago, to promote a TV show I worked for, he sexually assaulted me while we were posing for the picture,” Lind said in her account.

“He did not shake my hand. He touched me from behind. His wife Barbara Bush was at his side. I thought the joke was in bad taste, “he wrote.

(With information from ANSA)

Plaza de Mayo Grandmothers find Granddaughter 125

October 27, 2017.

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Estela de Carlotto announces the meeting of granddaughter 125. Photo: Telam

“Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo have the immense joy of communicating the restoration of the daughter of Lucia Rosalinda Victoria Tartaglia.” In this way, the Grandmothers, who just commemorated the forty years of searching, announced from the mouth of Estela de Carlotto the meeting of granddaughter 125.

Lucia, a political militant in La Plata, was kidnapped on November 27, 1977, at age 24. Since her family knew she was pregnant, they began the search for a child born in captivity. The samples that they contributed to the National Genetic Data Bank allowed the identification 38 years later.

Lucia was born on June 6, 1953 in Santa Rosa, La Pampa. Her family called her “La Flaca”. She moved to the city of La Plata where she studied law and was a member of the Peronist University Youth. “For a year, efforts on the part of her family to locate Lucia were in vain. They, had no news of her until, in November 1978, a year after her disappearance, her brother, Aldo Tartaglia, received a first letter from Lucia where she related that she was detained.

In another letter, she said that she was pregnant and expected to give birth in early 1979, “says the statement that Estela de Carlotto just read when announcing ” Today we find another granddaughter. “

In a democracy, her family was able to rebuild thanks to testimony from survivors that Lucia was kidnapped in the clandestine detention center known as “Atlético-Banco-Olimpo”. They knew it with the nickname of “anteojito”. The survivors reported that she was pregnant and was taken to give birth while in captivity.

Federal Criminal Oral Court Number 2 convicted fourteen members of the repressive forces, including Samuel Miara, on March 22, 2011, for the disappearance of Lucia.

“Thanks to the perseverance of our search and the human rights movement, today granddaughter 125 can know the truth about her origin,” said the statement from the Grandmothers.

(Taken from Pagina 12 )

Almost Half of German Women Have Suffered Sexual Abuse

Almost Half of German Women Have Suffered Sexual Abuse

October 29, 2017

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

According to information provided to the Council of the European Union (EU) in May this year, one in three women in the EU has been a victim of physical or sexual violence since the age of 15. | Photo: Reuters.

A survey carried out earlier month in Germany reveals that 43 percent of women and 12 percent of men admit to having suffered sexual harassment, according to data from British pollster YouGov.

The survey also reveals that one in six men confirms that they have sexually harassed someone. Eighteen percent of the men surveyed acknowledge that they have ever had inappropriate behavior that could be perceived as “disproportionate or sexual harassment.”

According to data from the study of more than 2,000 people, inappropriate touch (28 percent) and suggestive observations (24 percent) are common forms of harassment, occurring in 14 percent in places 13 per cent in the private sector and 10 per cent in work.

This study came after about thirty women, including assistants and members of the MEP team, reported having been harassed by several politicians in the European Union (EU).

(Taken from TeleSur)

Memorial to Cuban Martyrs in Grenada

Inauguration of Memorial to Cuban Internationalist Martyrs in Grenada

October 26, 2017

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Coinciding with the 34th anniversary of the death in combat of 24 Cuban internationalists during the United States’ invasion of Grenada in October 1983, a memorial was inaugurated in their honor at the Maurice Bishop International Airport.

This Memorial is the result of the work carried out during the years 2015 to 2017 with the contribution of Grenadian graduates in Cuba, Cuban collaborators, friends of solidarity, the Trade Union of Technical and Associated Workers (TAWU), the Airport Authorities and the government of Pomegranate. It is located in one of the areas occupied by the camps of Cuban collaborators who worked on the construction of the airport in the early 80’s of last century.

The event was chaired by Nickolas Steele, Minister of Health and Social Security, representing the government and the Cuban Ambassador, Maria Caridad Balaguer Labrada. Minister Steele referred to the contribution of the Cuban collaboration to the development of Grenada, in particular to the construction of the airport. She highlighted the spirit of solidarity of of our people despite their economic limitations, while denouncing the cruel economic, commercial and financial blockade imposed by the US government against Cuba for more than 55 years.

The ceremony also included Dr. Terence Marryshow, on behalf of the Grenada-Cuba Friendship Association. He highlighted the historic relations of friendship between the two peoples and referred to the heroism of the Cuban internationalists who had fallen during the invasion. Wendy Williams, General Manager of the Airport, stressed that the Memorial is part of the heritage of that institution and will be a place of permanent tribute to the 24 Cuban internationalist martyrs.

In her address, the Cuban Ambassador expressed her gratitude for the support she received for the realization of this work. It was the result of the historic friendly relations between the peoples of Cuba and Grenada and a symbol of heroism, humanism and solidarity as an expression of internationalism. Cuban people. Ariel Jiménez, a UNECA collaborator, later conducted the solemn roll call in honor of the 24 martyrs and paid a minute’s silence in tribute.

The ceremony was attended by Senators Andre Lewis, President of the Council of Trade Unions of Granada (GTUC) and Peter David; the Ambassador of Granada in Cuba, Claris Charles; Jorge Guerrero Veloz, Ambassador of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and officials of that diplomatic mission. Other government officials, Cuban collaborators, representatives of the trade union movement, friends of solidarity, graduates in Cuba and resident Cubans also attended.

Argentine Cinema Mourns Federico Luppi

Argentine Cinema Mourns Federico Luppi

Translated and Edited by Walter Lippmann.

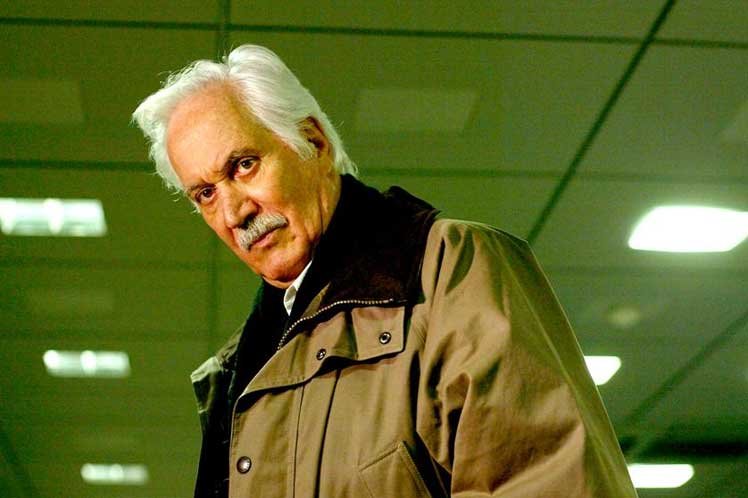

Buenos Aires, Oct 20 (Prensa Latina) He was 81 years old but for those who knew him up close, he had a young, cheerful heart and an enviable capacity for work, today the Argentineans say goodbye to one of their greatest actors, the great Federico Luppi .

Although he had been hospitalized several days ago due to a health problem that had been dragging on since his head was hit last April, the news has had an impact on the cultural media of the country and especially those Argentines who lived and dreamed of their actions.

Luppi, Time of Revenge, Labyrinth of the Faun, Common Places, Martin Hache, Cronos and many other films, died this morning at the Favaloro Foundation, where he remained hospitalized waiting for a transfer to another clinic to start a rehabilitation process.

The blow to his head produced a cerebral clot while he worked. In just six months his life went out but not the indelible mark left in Latin American and international cinema in more than 70 films, many of them multi-award winning. ‘Never’, he said sharply when one or another journalist asked him if he planned to retire one day and he kept his word, because despite his health complications, he was about to start a theatrical tour with the piece Las ultunas lunas, a play about old age, directed by his wife Susana Hornos.

On Twitter, messages weep over Luppi. He died a big figure, perhaps the most repeated word to say farewell to this actor, considered one of the most versatile interpreters of his generation.

Some pay homage with photographs and eternal thanks, others publish some of the most memorable scenes of their performances to recall it.

‘I am happy to be alive at this age, to have done so many things in Argentina and still be able to recount them. And I would like, yes, in slightly fantastical terms, to descend slowly through the dark side of the moon, but with dignity,” said this cinematic icon, who left for eternity today.

rc / may

The Contradictions of the U.S. Left

The Contradictions of the U.S. Left

By Manuel E. Yepe

http://manuelyepe.wordpress.com/

Exclusive for the daily POR ESTO! of Merida, Mexico.

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

The dream of creating a super-majority left-wing party in the United States from the ashes of the old Democratic party could be achieved overnight if Senator Bernie Sanders stopped working against the generation of young people who energized his campaign in the United States. confrontation with Hillary Clinton.

That is the idea put forth by the American writer, professor and political activist Gail McGowan Mellor in an article by her published on Huffington Post on September 27.

It is estimated that two-thirds of voters in the US are opposed to the endless wars waged by their country, the granting of subsidies to large corporations and corruption. They want to support environment, public safety, science and social justice. If they were able to unite, they would roll in any suffrage.

At present, there are those who work for the creation of a new great party of the left. They do not do it with a retail approach, because those who have this commitment are 60% of the total number of voters and 78% of the independents, says Mellor.

But several times in the last year the projected new self-organized progressive party has been close to becoming viable and has been blocked by Sanders, who has prioritized the unification and cleansing of the deeply divided and corrupt Democratic party, to which he himself does not belong.

US Senator Bernie Sanders was a 2016 presidential candidate promoted by progressive democrats from the Democratic Party. They were determined to clean up US policy, get out of its endless wars, restore security networks and fight climate change. But they had not found, at the federal level of the two establishment parties, someone who did not receive money from large corporations.

Bernie was an independent politician (without a party) who, 42 years ago, had held local and federal political positions without receiving partisan support or corporate money. A convincing politician, well-informed and passionate, but unknown at the national level, he was raised to the political limelight and to victory by young people between 18 and 50 years of age, known as the millenials). They average 37 years of age and aim at making changes in culture and politics, without imperialist aims and in favor of a democratic reconstruction of society.

At various times, Sanders rejected calls from many of the “millennials”, that he should leave the Democratic trusteeship and create a new party. But, instead of setting this as a goal, Sanders insisted that he could restore the Democratic Party to its old party party glory.

Without military in the divided and corrupt Democratic party, whose supporters barely represent 28% of the registered electorate, Sanders decided to work to achieve the reunification of it. To this end, he called on his supporters to register as Democrats, to the detriment of the progressive ranks that had promoted him and that, for that reason, would be divided and weakened.

The Democrats had accepted him as their presidential primary candidate because it gave them a competitive image that legitimized Hillary Clinton, their pre-determined candidate. The Democratic leadership calculated that beating Bernie would be an easy task for her. In fact, thanks to the millennial generation, Bernie demonstrated, from the first month of the campaign, that in a few hours he could gather an enthusiastic crowd in any city, something that Hillary could not do despite the abundant corporate money she had.

But neither Sanders nor his supporters knew that the Democratic primaries, with their fabulous public expenditures, are always fraudulent and their outcome is predetermined behind closed doors. And the most serious thing is that the party sees this as its right.

At various times, Sanders rejected the idea of many in the millennial generation, of getting out of the Democratic trusteeship and creating a new left party. Not a few of them thought they’d been cheated by the Democratic Party, and betrayed by Sanders. The rigged Democratic primaries ended in June 2016 with the designation of Hillary as party candidate.

Polls showed that Clinton and Trump were then neck-and-neck, four months before the November vote.

Subsequent polls have shown that in the 2016 elections, Sanders would have swept Trump. One of them suggested that Sanders would have obtained 56% of the vote, “an avalanche.”

As an aspiring Democratic presidential candidate, Sanders told TIME magazine that what he was waging was not an election campaign but a “movement leading to a revolution for which he was trying to create political awareness.”

October 23, 2017.

Indiscipline Penalty for Industriales Manager

National Baseball Directorate reports on penalty for Industriales manager

October 31, 2017

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann.

The National Baseball Directorate (DNB) informs our fans that the penalty applied to the manager of the Industriales, Víctor Mesa Martínez, was due to an act of indiscipline committed at the Bella Habana hotel, belonging to the Islazul chain.

The incident, which involved Mesa Martinez and one of the security managers of the installation, occurred last Thursday night, after concluding the first game of the sub-series that the Industriales played against Pinar del Río at the Latin American stadium.

Authorities from the capital, INDER, the Ministry of Tourism and the Islazul chain analyzed in detail what happened, and once the facts were clarified, the DNB proceeded to apply the corresponding measure, in line with the level of seriousness of what had happened.

The evaluation of what happened advised suspension of the manager for a sub-series, which corresponds to the one that those from the capital dispute in front of Granma in Bayamo.

This confirms the principle that discipline is inviolable in all venues of our National Series, and that the weight of the established regulation will fall on those who violate it.

The DNB also wants to explain that, as a rule, it does not provide the details of the events for which its athletes, coaches, affiliates and managers are given penalties, in order to protect the moral integrity of those involved and not to affect the internal dynamics of a team or work collective.

National Baseball Directorate

Estela Bravo: The Many Eyes of Her Camera

- English

- Español

Estela Bravo

The Many Eyes of Her Camera

By: Gilda Fariñas Rodríguez

Posted: 08/10/2015

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Estela and Mario Bravo

The United States, 1953. The call is to meet in front of the White House in Washington to support the campaign for the lives of the couple Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, condemned to die in the electric chair *. Estela Bravo is a 20-year-old daughter of a union leader, studying sociology and working for the furrier’s trade union in New York. Before leaving, she buys an eight-millimeter camera to film what would happen at the rally.

Upon arrival, two children catch her eye. They are the small Rosenberg children who are next to the demonstrators demanding mercy for their parents. That painful image is the first to be captured with her camera. Images and facts mark and set the course of her life. “I could not believe they would do something like that to you. That execution of the Rosenberg couple was always with me. “

This defined Estela Bravo’s existence from the political and personal point of view. That same year, she traveled to Europe as part of the delegation of her country participating in the Fourth World Youth Festival in Bucharest and the Third World Student Congress. In Warsaw, she also came to know Ernesto Bravo, the Argentine student leader with whom she has shared love, home, three children, two grandchildren and an impressive cinematographic work for almost 60 years.

Married in Argentina in January 1956, Estela and Ernesto decided to settle in Cuba, in 1963, after he received a contract to work as a professor of biochemistry at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Havana. She also does radio and television programs and organized the memorable Encuentro de Cancion Protesta (Protest Song Encuentro) in 1967. It was an event that would lead to the creation of the Center for Protest Song that Estela herself would direct.

From that event, she kept some memories that she now shares with Mujeres. “The first time the song Hasta Siempre, Comandante was sung, was in that Encuentro. Carlos Puebla wrote it when Che Guevara left Cuba. It was also the first time that Silvio, Pablo, and Noel sang together. “

It was in this same Casa that the multiple-award-winning filmmaker returned. Now, to donate to the archives of the Library a part of her more than 50 documentaries. With these she has registered the diversity of contexts and realities, with its human and divine conflicts, its migratory processes, its good actions, its political and social complexities, their barbarities, their injustices, their wars, their peace pacts, their joys, their dramas, their heroics, testimonies and truths that shake and hurt as they fill the soul with tenderness and love.

There they are to confirm it Those Who Left, Los Marielitos, Missing Children, Debtor Children, Holy Father and Glory, Cuba-South Africa, after the battle, Miami-Havana, Nelson Mandela in Cuba, The Excludables, Operation Peter Pan, Closing the Circle in Cuba, Fidel, The Untold Story.

FROM NEW YORK TO HAVANA, THE BRAVOS

New York University (NYU) is facing the arduous and expensive task of digitizing the filmography of Estela and Ernesto Bravo. It is a project that will guarantee the durability of this historic and universal heritage.

“We needed to clean up and digitize many of our files. NYU kindly offered to do the work. That is a very costly process, and we do not have enough resources to conduct it. We must bear in mind that each material was filmed and recorded with formats and equipment that are already obsolete,” Estela explains. She thanks the cooperation and donations received from “people who appreciate our documentaries to finance the digitization of films .”

Last January, Casa de las Americas received the good news that the Bravo couple had decided to donate much of that restored material.

“We already have other documentaries, passed on to the new technology, in our hands. That way, all the documentaries will be in the libraries of New York and of Casa so that the public has free access to them, which gives us great satisfaction “.

With marked jubilation, Estela mentions a message sent by NYU where she lea that they had shown, “the film Conversando con García Márquez on his friend Fidel in this center for advanced studies. A hundred people were unable to get in. It was all a success!”

THE VOICES OF HER CAMERA

It’s a Sunday in April at midday. Estela Bravo opens her home and part of her life to Mujeres magazine. We spoke in a room where there are plenty of portraits of her children (two women and one man), as well as her two grandchildren (woman and man). Pictures with posters of the Protest Song Encuentro and some works of art cover the walls. A picture of wood stands out. Estela is smiling between Nelson Mandela and Fidel Castro. It’s an image of which, of course, she is very proud.

“It was in 1991. It turns out that Mandela and I were talking at a reception where Fidel was coming to speak, and that’s when we took the picture. Having been there makes me feel very special; to be a woman with enormous luck because it is to be among the two most certainly important men of our time. I met Mandela in Namibia, during the celebration of Independence Day; From that moment I’ve also kept a photo with him. Later I saw him again when he was in Cuba.

There are many other images of memorable moments for Estela. These figures confirm the intensity with which this woman, born on June 8, 1933 in New York, has lived and created: major world leaders, political and religious figures, social leaders, artists, poets, writers, dear friends and friends and protagonists of her documentaries. In addition to numerous prizes, decorations, and memories that she leafs through with the same nostalgia with which she reads the small note next to a drawing, sent by the (recently-deceased) Uruguayan writer, Eduardo Galeano. “I would like to have as many eyes as the camera of Estela Bravo.” She is silent for a few moments, and her eyes seem to be damp.

Respectful of her sadness, I remain silent. She smiles with a warm tenderness as if distressed by the raw quality of her memories. So we talked a little more about her audacious cinematic experiences.

“My career has not been without difficulties when filming, to obtain testimonies, although that happens to every person seeking information. However, I have always received help from many people, and many doors have been opened to me. In the end, I feel a deep satisfaction because the public sees my films, comments on them, they stop me in the street … and that gives me the biggest bliss “.

Are you fond of a particular documentary?

“I am fond of each of the works we have done. Because if, through a film, we can transmit to people what we feel, then we make the stories of many people imperishable. Certainly, there are some jobs that one wants more than others, for example, Operation Peter Pan … Today I maintain ties with all those young people. Similar affection provokes me The Found Children of Argentina, for which I remained a great friendship with Estela Carlotto, president of the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo. I remember when she found her grandson (who is 114[?]) I went back to the documentary and added it at the end. We even made a new version that ends with the testimony of her embracing her 37 year-old grandson.

“The film The Holy Father and Gloria is the most-awarded of all that we have done. Personally, I have a deep affection for this documentary, as well as Carmen Gloria **, her protagonist who is married today and has a beautiful girl. “

Will Estela Bravo ever stop making films?

“I’m almost 82 years old. I cannot believe it! It is no longer the same, but I will always try not to stop working. Right now we are immersed in a new production, but I do not want to speak, for the moment, of what we are doing. “

Even if she does not want to reveal to this magazine the details of her new documentary, it is evident to us that once again we will be confronted with stories, experiences, dramas, and joys, images and voices captured in an exceptional way by this woman’s brave camera.

Estela Bravo

Los tantos ojos de su cámara

Por: Gilda Fariñas Rodríguez

Publicado: 10/08/2015

Estados Unidos, año 1953. La convocatoria es reunirse frente a la Casa Blanca, en Washington, para apoyar la campaña por la vida de los esposos Ethel y JuliusRosenberg, condenados a morir en la silla eléctrica*. Estela Bravo tiene 20 años, es hija de un líder sindical, estudia sociología y trabaja para el sindicato de peleteros, en Nueva York. Antes de salir, compra una cámara de ocho milímetros para filmar lo que ocurriría en el mitin.

Al llegar, dos niños llaman su atención. Son los pequeños hijos Rosenberg que están junto a los manifestantes que pedían clemencia para sus padres. Aquella dolorosa imagen es la primera que capta con su cámara. Imágenes y hechos que marcan y determinan su vida. «Yo no podía creer que les harían algo así. Esa ejecución de los esposos Rosenberg quedó siempre conmigo».

Así quedaba definida la existencia de Estela Bravo desde lo político y personal: ese mismo año 53 viaja a Europa como parte de la delegación de su país que participa en el IV Festival de la Juventud, en Bucarest, y al III Congreso Mundial de Estudiantes, en Varsovia; también conoce a Ernesto Bravo, el dirigente estudiantil argentino con el que ha compartido amor, hogar, tres hijos, dos nietos y una impresionante obra cinematográfica por casi 60 años.

Casados en Argentina en enero de 1956, Estela y Ernesto deciden instalarse en Cuba, en 1963, luego de que él recibiera un contrato para trabajar como profesor de Bioquímica en la Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad de La Habana. En tanto ella hace programas de radio, de televisión y organiza en la Casa de las Américas el memorable Encuentro de la Canción Protesta, en 1967. Un suceso que daría paso a la creación del Centro de la Canción Protesta que la propia Estela dirigiría.

De aquel suceso rescata algunos recuerdos que ahora comparte con Mujeres. «La primera vez que se cantó la canción Hasta siempre, comandante, fue en ese Encuentro. Carlos Puebla la escribió cuando el Che Guevara salió de Cuba. También fue la primera vez que Silvio, Pablo y Noel cantaron juntos».

Precisamente, a esta misma Casa retorna la multipremiada cineasta. Ahora, para donar a los archivos de la Biblioteca una parte de los más de 50 documentales con los que ha registrado la diversidad de contextos y realidades, con sus conflictos humanos y divinos, sus procesos migratorios, sus buenas acciones, sus complejidades políticas y sociales, sus barbaries, sus injusticias, sus guerras, sus pactos de paz, sus alegrías, sus dramas, sus heroicidades… Testimonios y verdades que estremecen y duelen lo mismo que llenan de ternura y amor el alma.

Ahí están para confirmarlo Los que se fueron, Los Marielitos, Niños desaparecidos, Niños deudores, El Santo Padre y la Gloria, Cuba-Sudáfrica, después de la batalla, Miami-La Habana, Nelson Mandela en Cuba, Los excluibles, Operación Peter Pan, cerrando el círculo en Cuba, Fidel, la historia no contada…

DE NUEVA YORK A LA HABANA, LOS BRAVO

La Universidad de Nueva York (UNY) está encarando la ardua y carísima faena de digitalizar la filmografía de Estela y Ernesto Bravo. Una labor que garantiza la perdurabilidad de ese patrimonio histórico y universal.

«Necesitábamos limpiar y digitalizar muchos de nuestros archivos. La UNY se ofreció, gentilmente, para hacer el trabajo. Ese es un proceso costosísimo y nosotros no tenemos suficientes recursos para asumirlo. Hay que tener en cuenta que cada material fue filmado y grabado con formatos y equipos que ya son obsoletos», explica Estela, quien agradece la cooperación y donativos recibidos de «personas que aprecian nuestros documentales para financiar la digitalización de las películas».

En enero pasado, la Casa de las Américas recibía la buena noticia de que el matrimonio Bravo decidió donar buena parte de ese material restaurado.

«Ya tenemos otros documentales, pasados a la nueva tecnología, en nuestras manos. De ese modo, podrá estar toda la documentalística en las Bibliotecas de Nueva York y de Casa para que el público tenga acceso libre a ella, lo cual nos da mucha satisfacción».

Con marcado júbilo, Estela menciona un mensaje enviado por la UNY donde le comunican que exhibieron, en ese centro de altos estudios, «la película Conversando con García Márquez sobre su amigo Fidel. ¡Cien personas se quedaron sin poder entrar. Fue todo un éxito!»

LAS VOCES DE SU CÁMARA

Domingo de abril al mediodía. Estela Bravo abre su casa y parte de su vida a la revista Mujeres. Conversamos en una sala donde abundan retratos de sus hijos (dos mujeres y un hombre), al igual que sus dos nietos (mujer y varón). Cuadros con afiches del Encuentro de la Canción Protesta y algunas obras de arte cubren las paredes. Sobre un mueble de madera resalta una foto. Estela sonríe entre Nelson Mandela y Fidel Castro. Una imagen de la que, por supuesto, se siente profundamente orgullosa.

«Fue en el año 1991. Resulta que Mandela y yo estamos hablando en una recepción y Fidel se acerca para conversar y es cuando nos toman la foto. Estar ahí me hace sentir muy especial; ser una mujer con una suerte enorme porque es estar entre los dos hombres, con toda seguridad, más importantes de nuestro tiempo. Yo había conocido a Mandela en Namibia, durante la celebración del Día de la Independencia; de ese momento también guardo una foto con él. Después lo volví a ver cuando estuvo en Cuba.

Hay otras muchísimas imágenes de instantes memorables para Estela. Manifiestos gráficos que confirman la intensidad con que esta mujer, nacida el 8 de junio de 1933, en Nueva York, ha vivido y creado: importantes líderes mundiales, figuras políticas y religiosas, dirigentes sociales, artistas, poetas, escritores, entrañables amigas y amigos y protagonistas de sus documentales. Además de numerosos premios, condecoraciones y recuerdos que hojea con la misma nostalgia con que lee la pequeña nota junto a un dibujo, enviada por el escritor uruguayo (recién fallecido), Eduardo Galeano. «Yo quisiera tener tantos ojos como la cámara de Estela Bravo». Queda callada unos instantes y sus ojos parecen humedecerse.

Respetuosa de su tristeza, guardo silencio. Sonríe con una ternura cálida, como apenada de la desnudez de sus recuerdos. Entonces, hablamos un poco más de sus audaces experiencias cinematográficas.

«Mi carrera no ha estado exenta de dificultades a la hora de filmar, de conseguir testimonios; aunque eso le ocurre a toda persona que busca información. Sin embargo, siempre he recibido ayuda de numerosas personas, y muchas puertas se me han abierto. Al final, experimento una profunda satisfacción porque el público ve mis películas, las comenta, me paran en la calle… y eso me proporciona la más grande dicha».

¿Siente cariño por un documental en particular?

«Le tengo cariño a cada uno de los trabajos que hemos realizado. Porque si a través de una película podemos trasmitir a la gente eso que sentimos, entonces hacemos imperecedera la historia de muchas personas. Ciertamente, hay algunos trabajos que una quiere más que otros, por ejemplo, Operación Peter Pan… Hoy mantengo relación con todos esos muchachos. Similar cariño me provoca Los niños encontrados de Argentina, del que me quedó una gran amistad con Estela Carlotto, presidenta de las abuelas de Plaza de Mayo. Recuerdo que cuando ella encontró a su nieto (que es el 114) volví al documental y lo agregué al final. Incluso, hicimos una nueva versión que finaliza con el testimonio de ella abrazada a su nieto de 37 años.

«La película El Santo Padre y la Gloria, es la más premiada de todas las que hemos realizado. En lo personal, siento profundo cariño por ese documental, al igual que por Carmen Gloria**, su protagonista que hoy está casada y tiene una preciosa niña».

¿Nunca dejará de filmar Estela Bravo?

«Casi voy a cumplir 82 años. ¡No lo puedo creer! Ya no es igual, pero siempre trataré de no dejar de trabajar. Ahora mismo estamos inmersos en una nueva producción, pero no quiero hablar, por el momento, de lo que estamos haciendo».

Aun cuando ella no quiera revelar a esta revista los detalles de su nuevo documental, nos resulta obvia la expectativa de que, una vez más, estaremos frente a relatos, vivencias, dramas y alegrías, imágenes y voces captadas, de manera excepcional, por la cámara brava de esta mujer.

Poor Puerto Rico

- English

- Español

Poor Puerto Rico

By Manuel E. Yepe

http://manuelyepe.wordpress.com/

Exclusive for the daily POR ESTO! of Merida, Mexico

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Sad is the situation that Puerto Ricans are going through. The island was recently devastated by a deadly hurricane that crossed its entire length. Hovering over it, sharpened vehemence, is another phenomenon, one more criminal, prolonged and bloody. its condition of being a colony of the United States..

The Federal Agency for Emergency Management (FEMA) has bureaucratically hindered the distribution of aid that has been able to reach Puerto Rico. There are reports that claim that most of the aid for the disaster is still on the docks of San Juan, the capital.

Fifty percent of the population still lacks access to drinking water. The power grid is so damaged that 85 percent of the population still does not have electricity. The lack of fuel and energy hinders the functioning of hospitals and puts at risk the lives of the most vulnerable: children and the elderly. The death rate is increasing, especially in rural areas.

In the midst of the greatest devastation on the island, due to the passage of Hurricane Maria, Puerto Ricans were severely offended when President Trump blamed them for the humanitarian crisis the island was facing.

“Texas and Florida are doing very well, but Puerto Rico, which already suffered from a damaged infrastructure and massive debt, is in trouble,” Trump wrote in his Internet account, comparing the rapid recovery of two of the nation’s major states hit by hurricanes. In the process of degradation that affected them, with the tragedy suffered by their country in the Caribbean because of the most violent hurricane in Borinquen history, with sustained winds of 155 mph (250 km/h).

Trump’s angry reaction to the atrocious humanitarian crisis in Puerto Rico exacerbated by the meteorological phenomenon in the conditions of a country deeply hurt by decades of colonialism and neoliberal policies, has created an explosive situation.

Puerto Rico currently has a debt of $73 billion to its creditors, which is equivalent to the total of its GDP. The commonwealth officially is in default (unable pay the debt). Neither the US government nor the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have presented any solution.

In reality, the country’s debt began to grow in the 1970s. Its economy, since the middle of the last century, was based mainly on the pharmaceutical industry. But with the appearance of the maquiladoras in Mexico and Asia, this sector has been moving to those regions in search of cheaper labor and higher productivity.

Currently, the official unemployment rate in 16 municipalities is 20 percent and in 61 others it exceeds 12 percent, although in reality the real unemployment rate is much higher than the official rate. Some 45 percent of the island’s 3.5 million people live in poverty and 83 percent of children live in poor areas. In a desperate act, last may Governor Rosselló cut the budget by $674 million dollars. This affected the health care system, education, various social programs and the University of Puerto Rico. As a result of the economic crisis, 144,000 Puerto Ricans left the island in search of employment.

Puerto Rico and Cuba have shared destinies as Spanish colonies. Their emancipatory struggles were interrupted by an opportunistic US intervention that sought to adjudge the remnants of the Spanish colonial empire in disgrace. Cuba achieved that the military occupation of the then nascent US imperialism was limited to 4 years and gave way to the proclamation in 1902 of an independent pseudo-republic. January 1959 brought, through the revolution, a genuine independence, although at the cost of a bloody daily battle against American hegemonic appetites.

118 years ago Washington seized Puerto Rico and the other vestiges of the Spanish empire in the Western Hemisphere. When neoliberalism broke onto the scene, to provide an injection of life to capitalism in crisis, the impulse towards the privatization of everything that existed caused extraordinary damage in Puerto Rico. Living conditions deteriorated with the disappearance of government funds for social programs and jobs. The island’s infrastructure was devastated by a campaign to convert everything from roads and public services to the education system into private for-profit companies.

Colonialism imposed an unpayable debt on Puerto Rico. Now it has had a dictatorial junta imposed on it to ensure that this debt is paid, even at the cost of a humanitarian crisis for the Puerto Rican people. Boricuas are demanding, specifically, that this debt be audited and that it be determined which part of it is legitimate and who is responsible for having assumed it.

October 30, 2017

Pobre Puerto Rico

Por Manuel E. Yepe

http://manuelyepe.wordpress.com/

Exclusivo para el diario POR ESTO! de Mérida, México

Triste es la situación por la que atraviesan los puertorriqueños; recién arrasada su isla por un mortífero huracán que la atravesó por toda su extensión, se cierne sobre ella con agudizada vehemencia otro fenómeno más criminal, prolongado y cruento, su condición colonial respecto a Estados Unidos.

La Agencia Federal para el Manejo de Emergencias (FEMA, según las siglas en inglés) ha obstaculizado burocráticamente la distribución de la ayuda que ha podido llegar a Puerto Rico. Hay reportajes que afirman que la mayor parte de la ayuda para el desastre aún se encuentra en los muelles de San Juan, la capital.

Cincuenta por ciento de la población carece aún de acceso a agua potable y la red eléctrica está tan dañada que el 85 por ciento de la población aún no tiene electricidad. La falta de combustible y energía obstaculiza el funcionamiento de hospitales y pone en riesgo la vida de los más vulnerables: los niños y ancianos. La tasa de mortandad está aumentando sobre todo en áreas rurales.

En medio de la mayor devastación de que se tenga memoria en la isla a causa del paso del huracán María, los puertorriqueños se sintieron duramente ofendidos cuando el presidente Trump les culpó por la crisis humanitaria a la que estaba abocada la isla.

“Texas y Florida van muy bien, pero Puerto Rico, que ya sufría una infraestructura dañada y una deuda masiva, está en problemas”, escribió Trump en su cuenta de Internet comparando la rápida recuperación de dos de los principales estados de la nación ante huracanes en proceso de degradación que les afectaron, con la tragedia sufrida por su colonia en el Caribe a causa del cruce por su territorio del huracán más violento que haya azotado a Borinquen en toda su historia, con vientos sostenidos de 155 m/h (250 km/h).

La reacción iracunda de Trump ante la atroz crisis humanitaria de Puerto Rico agudizada por el fenómeno meteorológico en las condiciones de un país profundamente herido por décadas de colonialismo y políticas neoliberales, ha creado una situación explosiva.

Actualmente Puerto Rico tiene una deuda de 73 mil millones de dólares a sus acreedores, lo que equivale al total de su PIB. El Estado Libre Asociado oficialmente está en default (incapacidad de pagar la deuda) sin que ni el gobierno norteamericano ni el Fondo Monetario Internacional (FMI) hayan presentado solución alguna.

En realidad la deuda del país empezó a crecer a partir de los años 1970. Su economía desde la mitad del siglo pasado estaba basada principalmente en la industria farmacéutica pero con la aparición de las maquiladoras en México y en Asia, este sector se ha estado trasladando a aquellas regiones en busca de mano de obra más barata y de mayor productividad.

Actualmente el índice oficial de desempleo en 16 municipios es del 20 por ciento y en otros 61 supera al 12 por ciento, aunque en realidad la tasa real de desempleo es mucho más alta que la oficial. Un 45 por ciento del total de 3,5 millones de habitantes de la isla viven en la pobreza y el 83 por ciento de los niños viven en áreas pobres. En acto desesperado, el gobernador Rosselló recortó en mayo pasado el presupuesto en 674 millones de dólares afectando el sistema de salud, la educación, varios programas sociales y la Universidad de Puerto Rico. Como resultado de la crisis económica 144.000 puertorriqueños abandonaron la isla en busca de empleo.

Puerto Rico y Cuba han compartido destinos como colonias de España cuyas luchas emancipadoras fueron interrumpidas por una oportunista intervención estadounidense que pretendió adjudicarse los remanentes de imperio colonial español en desgracia. Cuba logró que la ocupación militar del entonces naciente imperialismo de Estados Unidos se limitara a 4 años y diera paso a la proclamación en 1902 a una seudorepública independiente que en enero de 1959 trajo, revolución mediante, una independencia verdadera, aunque al costo de librar una cruenta batalla cotidiana contra los apetitos hegemónicos estadounidenses.

Hace 118 años que Washington se apoderó de Puerto Rico y los demás vestigios del imperio español en el hemisferio occidental. Cuando el neoliberalismo irrumpió en la escena para proporcionar una inyección de vida al capitalismo en crisis, el impulso hacia la privatización de todo lo existente causó perjuicios extraordinarios en Puerto Rico. Se deterioraron las condiciones de vida al desaparecer los fondos gubernamentales para fines sociales y los empleos. La infraestructura de la isla quedó devastada por una campaña para convertirlo todo, desde las carreteras y los servicios públicos hasta el sistema educativo, en empresas privadas con fines de lucro.

El coloniaje impuso a Puerto Rico una deuda impagable y ahora le ha impuesto una junta dictatorial para asegurar que se pague esa deuda, aunque sea al costo de una crisis humanitaria para el pueblo puertorriqueño. Los boricuas reclaman, justamente, que se audite esa deuda y se determine qué parte de la misma es legítima y quiénes son los respons

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

You must be logged in to post a comment.