June 16, 2017 16

Venezuela: Facts and Misinformation

Venezuela: Facts and Misinformation

Editorial

April 1, 2017

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Thanks to Nelson Valdes who brought this to my attention

and helped revise the translation for posting here.

The unfolding Venezuelan political crisis is being accompanied by an incessant media campaign that seeks to plant in international public opinion the idea that the South American country is going through a government-sponsored coup process that has little to do with reality.

This recent propaganda war against the democratically-elected Venezuelan government has been compounded in recent weeks by the political attacks originating at the Organization of American States –a multilateral organization presumably engaged in the pursuit of dialogue– and the rightwing and ultra-right regimes of the Latin American region

The facts are that the Venezuelan Constitution continues to be in operation, the president is still in office –which, in a presidential regime like the Venezuelan, makes it absurd to speak of the existence of a coup–, all constitutional guarantees are in force.

The internal life of all political parties and respect for freedom of expression persists. Paradoxically, those very constitutional rights are being used to describe the regime as a dictatorship. In addition, the notion that the legislative power was dissolved is no more than absurd, since no parliamentarian has been dismissed and the legislative assembly can resume its functions as soon as it complies with an order of the Supreme Court of Justice (TSJ) issued on January 5, 2016 .

The tale of a coup or self-coup by the government of President Nicolas Maduro is an uninformed interpretation of the decision adopted on Thursday, March 30, by the Constitutional Chamber of the TSJ, with which the TSJ assumed the powers of the National Assembly of Venezuela (ANV, Venezuela’s unicameral parliament), as it puts an end to the situation of contempt in which it finds itself caused by the illegal swearing in of three opposition deputies.

It should be remembered that the present situation of a prolonged confrontation between the Venezuelan right grouped in the Democratic Unity Table (MUD) and the Maduro government has its origin in the legislative elections of December 2015, when the opposition managed to snatch a majority from the pro-Chavez Parliament.

In the election then, large irregularities were verified and verified in the state of Amazonas were documented. This caused the annulment of the election of three MUD deputies and the high court also ordered the reinstatement of the corresponding votes. The opposition decided to use its parliamentary majority to swear in the legislators, in open violation of legality, and for that reason the courts declared the opposition in contempt by the TSJ.

It is also necessary to point out that the decision by which the TSJ temporarily assumes the powers of the assembly is based in Venezuelan law and responds to the need to unlock the operation of the oil sector, which is crucial to facing the serious economic crisis of the country.

In short, it is imperative to put an end to systematic disinformation that only exacerbates an already delicate conflict, and the outcome will determind the welfare and social peace of millions of Venezuelans. The Venuelans are the ones who must resolve their differences within the framework of their own laws, while the external actors who wish to contribute must do so while fully respecting the sovereignty of Venezuela and with the sole purpose of facilitating the implementation of resolutions adopted internally.

Is it Time to Change?

Is it Time to Change?

By Orlando Marquez

NUEVA PALABRA

February /2009 No. 182

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

After working for more than a year by request from the Washington Center for National Policies (CNP) a two-party team lead by former USA ambassador to Mexico James J. Jones and formed by Thomas Wenski, assistant bishop of Miami, University professor Max Castro, and Cuban American businessman Carlos Saladriga presented a report called “Cuba-United States Relations: time for a new approach” on January 23 2003.

In this 20-page report it was stated that “the United States will attain its goals with Cuba with a higher probability by using negotiation than by isolation”. The report didn’t recommend former President George W. Bush to lift the embargo. But, it recommended initiating a new policy and allowing American citizens to visit the Island. It also advised facilitating the sale of medicines and food products; to eliminate the limit set on money transfers to Cuban families; to review current legislations on Cuba, and facilitate scientific, professional and academic exchange. It recommended developing bilateral cooperation on issues of mutual interest like drug and people traffic, fighting crime and environmental protection. These recommendations were ignored at first, and a year later the government did just the opposite.

At the end of 2007 I met a former government official in Washington. Naturally, we talked about the United States and Cuba. He agreed with me that the isolation policy inherited, maintained and strengthened by his government had no followers. “So?” I asked. He talked about liberty, human rights… I agreed. I added that isolation had only created more problems and asked him if he thought China and Saudi Arabia, two of his country’s main associates, were good examples of liberty and human rights. He had no further arguments, and then he confessed that his superiors could not forgive, among other things, that former President Fidel Castro would have thought of launching a nuclear attack against the United States during the missile crisis, in 1962!… I was the one who ran out of arguments, because there is nothing to say when confronted with irrationality and passion. I must add that this government official did not agree with this policy, he only said that decision was out of his hands.

This issue has been treated very differently on our side! Certainly, there has been a lot of passion. Besides our “achievements in health and education” there has been no other issue more important in our national media than the evils of the United States. They have talked about presidential ineptitudes, economic crisis, social violence, racism (this may change somewhat after Obama’s election), police abuse, homeless, the millions of citizens without medical insurance, drug addicts… It would seem that every evil in the world is there, and only there, the worst, the most despicable. And, the attempt to distinguish between the American government and the “noble people of the United States” – that elect them- sounds absurd and untenable.

“A letter that put a mark on history” was the title chosen by Granma newspaper last year to accompany the fifty year old –four years before the missile crisis- letter they published. The letter was written by the Commander in Chief of the Rebel Army, Fidel Castro Ruz, to Celia Sanchez, after army planes had bombed the ‘bohio’ of a peasant with bombs made in the United States. In this letter the former Cuban President wrote; “When I saw the bombs they threw at Mario’s house I promised myself that the Americans will pay dearly for what they are doing now. After this war is over, I will start another war, longer and bigger: the one I am going to wage against them. I realize that this is my true destiny.” There is no proof that the former president kept on thinking the same way after the United States stopped selling armament to Fulgencio Batista’s government months later. This statement was not repeated later. Although it was reprinted, like this time on June 5. 2008, with a title that suggests, or intends to confirm, that our history is marked by eternal conflict with the United States.

Notwithstanding the fact that the United States government support of Fulgencio Batista’s government is criticizable, as is the fastidious and reprehensible interference in Cuban matters during the first half of the 20th century, Should our present and future history depend on the ill-fated attack on the humble home of a peasant that took place more than fifty years ago and on the feelings expressed in a letter written while those feelings were intense? Must we always suffer the consequences of what might have been, but didn’t happen, during the missile crises in 1962? I don’t think so.

During his campaign, Barack Obama, against all previously established molds, declared he was willing to talk to the leaders of all the countries considered as United States enemies, including Cuba. On our side, the will to establish a dialogue couldn’t be more evident, as President Raul Castro has declared more than once.

For many in his own country, Obama is still an enigma. And, for Cuba? Well, here, it is even more so. Many Cubans, including me, are waiting to see if the change in policy making in the United States and, therefore, in its external policy, also means a change in U. S, relations with Cuba.

However, Cuba is only pressing for Cubans. It is not very probable that Cuban issues will have a high priority for the new American government. Nevertheless, Cuba (with Cubans holding different points of view) shouldn’t be ignored. Cuba is too near, too active. It has a very large international and regional influence, as well as inside the United States. Cuba is too defying, and perhaps, it even has too much oil waiting to be extracted.

In spite of the willingness expressed by both presidents, some people have raised the alarm -both here and there – against a new status in the relations among the two countries. The ghostly remoras of the Cold War rise once more, ignoring the demands of millions of people. On that side some talk about the dangers of “recognizing” a dictatorship that never changes. On this side, those that always warned against an imminent military invasion, an argument that is already worn out, warn against a “cultural invasion” that can destroy us.

SOURCE: Original Spanish not available. Sorry!

Mario Conde’s Havana Noir

PAGINA 12 (Argentina)

Mario Conde’s Havana Noir

The investigations of Leonardo Padura’s detective are in audiovisual form now. Jorge Perugorria plays the detective who investigates a series of crimes in a colorful and decadent Cuba

The script of the series is based on four novels by the Cuban author.

FOUR SEASONS IN HAVANA, by NETFLIX

By Federico Lisical

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Los argumentos de la serie están basados en cuatro de las novelas del autor cubano.

“I decided to make a character who was in conflict with the reality he was living,” Leonardo Padura once told this newspaper. The Cuban writer was referring to Mario Conde, the officer who was the main character ofj his police novels and who now centers the NETFLIX miniseries Four Seasons in Havana (that since last Friday can be seen online). The series is based on stories in Padura´s four novels: Past Perfect, Winds of Lent, Masks, and Autumn Landscape.

This disenchanted but noble man, who does not seem to be a police lieutenant and has a great love for books, is interpreted by Jorge Perugorría. Almost to his regret, the best thing he knows how to do is solve mysteries and write up his wanderings with a typewriter. “There is no one better than Mario Conde to get into Havana, rummage through its darkness, and draw some light. That special insight the detective has, is particularly revealing. What I wanted to do was to make a kind of chronicle, a testimony of what recent Cuban life has been like. In each of his investigations, he reveals a sector of Cuban society, but also the humanity of a number of characters who live that reality day-to-day,” said the writer in another interview.

In total there are four episodes, ninety minutes each. They were directed by the Spaniard Felix Bizcarte, and the role of Padura himself in the adaptation was key, as well as that of his wife Lucia López Coll. Their intention was to preserve the tone of the novels and let the Cuban reality filter in naturally. What is the resulting Havana? One that shows its darkest and most sinful side. There is corruption, traffickers of all kinds –of drugs and influence– has been but there is also the dream of what the revolution could have been. Conde is a romantic who goes around throwing phrases for whoever wants to listen: “Havana has fallen so much that is has gone to shit”; “Cops investigating cops… What the hell is going on?”

The context is crucial as the books were published between 1991 and 1998 and reflected what was happening on the island after the end of the Cold War, the tightening of the embargo, and the regime’s opposite sides. As the author said, “… I learned from Hammett, Chandler, Vázquez Montalbán and Sciascia that a police novel can have a real relationship with the country’s environment; that it can denounce or touch concrete facts and not just imaginary realities.” “El Conde” moves about the capital of Cuba as a Philip Marlowe who suffers the heat, and fights his destiny, “doing what I have to do, but never what I really want to do.” The big difference with the iconic detective of suburban Los Angeles is that Conde is a cop. “It was totally unrealistic to have someone who was not a police officer investigate a crime in Cuba, especially if it was a murder,” Padura explained. But Conde also dreams of being a writer and that is what saves him.

This jaded subject is summoned to investigate the murder of a high school teacher while he is also looking into another case that has to do with his own past. In all of these there are several criminal associations. As in every noir police story, in addition to the investigations there are institutions tainted with indolence, elites complicit with business interests, femmes fatale, jazz music and seedy bars. Its main character is a researcher of the shadows but with a complex humanity and far from clichés. “Conde represents a generation of Cubans who believed in a country project that will never be, and feeds heavily on nostalgia. He’s a fucking nostalgic, as he defines himself, “said the actor who has the role.

The photography (by Spaniard Pedro J. Márquez) is one of the highest points of the production. The tone is twilight and oblivious to any “for export” intention. The rundown houses of the old quarters convey the stupor of the characters; and the danger in a harbor city when the sun goes down. The scenes of violence are given in unusual settings that can capture the audiences. In short, there are four genre stories within a very unique context that reflects the day-to-day life of the Caribbean city and its surroundings. One can easily perceive how the characters are linked: their body language, how they breathe and perspire, their unrefined speech that mispronounces sounds, how their food smells, and how they have sex. Four Seasons in Havana is, above all, a sensory experience. “Noir was never so colorful,” said one of the promotions for the miniseries; but it may be exactly the other way around.

Colombian Journalist Hernando Calvo Ospina’s Route

Once Again They Want To Change Colombian Journalist Hernando Calvo Ospina’s Route

Inconceivable branded a “terrorist” by the US, they diverted the Air France he was traveling on so it wouldn’t cross over US territory. Now, for the same reason, they made him change flights before boarding.

By Marina Mendez Quintero

May 27 2009 00:25:17 GMT

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Because we have become accustomed to living with an arrogance that has triggered two wars, it doesn’t surprise us that Washington has allotted itself the prerogative of including countries, organizations or innocent people in its “terrorist” lists.

But what is really unbelievable and is apparently an escalade into the absurd is that one of those people (without even having been notified of such charges!) has been forced in two consecutive instances to change the course of a trip because he “has been forbidden” to fly over United States territory.

Mind you, we are not talking about touching or stepping on [US soil]: it is simply the act of passing a thousand feet above it. Even when the subject- of course, unarmed! – and, without looking down, is only reading a newspaper, comfortably sitting in an airplane.

Now, sitting in front of the reporter, with that clear and candid smile that always accompanies the Colombian journalist and researcher Hernando Calvo Ospina, “the defendant” is still surprised.

“Nobody understands it, and I still do not understand it. I can not understand how they came up with this “level of hazard”, they have assigned me.

The first time was April 18 last, and the news spread like wildfire, turning into a scandal. Perhaps you read it in this same newspaper: an Air France plane full of passengers, in a Paris-Mexico route, had to change course in mid-flight because the U.S. did not allow it to fly across its territory. The reason they gave was that one of the passengers was a person who constituted “a threat to its national security”.

The change of course happened when we were reaching Mexico. It lengthened the trip and took the passengers to an unexpected excursion to Martinique. This was because the fuel they had was not enough to take all those turns and the plane had to be refueled. Some children got sick and vomited, and many adults arrived finally in Mexico with leg cramps.

The person most surprised was Calvo Ospina himself when they told him he was the cause of the detour. He was the ‘unwelcome” person in the air above the U.S.

The worst thing is that this strange situation repeated itself, more or less the same, a few days ago.

He was traveling to Havana from Paris, where he resides, and three hours before boarding the phone rang. ‘Hernando Calvo Ospina? This is Air France calling. We can not let you board the plane because it will pass through U.S. airspace to enter Cuba’. These were more or less the words they used.

They changed the tickets and “sent” him via Madrid.

Calvo Ospina now wonders whether Air France gives U.S. authorities the passenger lists of its company’s flights that will cross U.S airspace.

– What will you do when you get back to Paris?

– First, I have to ask Air France for an explanation. But I think I will sue them and-most importantly- the United States on the issue of my image.

– How do you feel, a man like you, who has fought terrorism for so long, and is now in one of those lists?

– Look, it’s a very difficult situation because one already knows what they could do: put me in prison, torture me. But, the thing is. You think: What did I do that was so bad? I’ve never shot a gun! I have spoken with the French authorities, and they also do not understand it. I can not understand it either. Are there other games going on under the table to put pressure on someone through me? Where or whom? It is the first time in the history of Air France that this happens, there is no precedent.

“French authorities also did not understand that the course of the plane was altered when president Obama was meeting with almost all Latin American presidents (Summit of the Americas), and told them: ‘We are going to change our ways, we will respect. “

– Why do you think you were included?

– What I have been able to find out from colleagues and friends, is that there seems to be four reasons: the articles I have published against the Colombian government, the articles I’ve done against the U.S. policy towards Latin America, my relationships and interviews with the leaders of Colombian guerrillas, and my relations with countries ‘hostile’ to the U.S.

“Now, I do not know which Latin American countries are hostile to the U.S., because what I do know is that the U.S. is the one who has been hostile to several Latin American countries. But I do not think that these four “reasons” are enough to justify all the things that happened.”

I did not ask him what route he will use to return to France … In any case, Hernando Calvo Ospina has a clear conscience. His only arsenals are the dozens of articles where he has denounced many of the White House dirty policies, and a dozen books in which he speaks of a real terror: the one successive U.S. administrations wage against Latin America.

Alejandro Armengol

Alejandro Armengol

About Me

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Alejandro Armengol was born in Cuba and has lived in the United States since 1983. He studied Electrical Engineering and Nuclear Physics in the University of Havana, and holds degrees in Psychology and Sociology, two professions he has never practiced. A journalist for more than fifteen years, his work has been published in journals and newspapers in the United States and Europe, and some of them have received the National Association of Hispanic Publications award. He writes a weekly column in El Nuevo Herald and another in the online newspaper Encuentro en la red. He is an associate professor in the University of Miami. In 2000 he published his books La galería invisible (short stories) and Cuaderno interrumpido (poems), and in 2003 his book Miamenses y Más. You can write to him at aarmengol@herald.com

I received clarification from the State Department’s Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs about the statements made by Thomas Shannon, Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs, incorrectly published by the news agency EFE since the very beginning, as I said both in my blog and my Monday column.

It only remains for me to add that, even if it comes out on Monday, I write my column on Thursday or Friday, so that the relevant page in El Nuevo Herald is ready for print right on Friday. I had not come to the newspaper since last Thursday, so I have just found out about this information, which I now pass on to the readers of my column and to Cuaderno de Cuba:

In his “retirement”, Fidel swims, writes, reads the papers and studies Darwin

Clarín

In his “retirement”, Fidel swims, writes, reads the papers and studies Darwin

By Hinde Pomeraniec

December 3, 2009

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

All the news we’ve had until now about Fidel Castro’s condition after almost three years of nonstop surgery and illness were his photographs with various heads of State and the articles he writes for the Cuban press on a regular basis. On Saturday, the Argentinean political scientist and sociologist Atilio Boron was in for a surprise while having lunch at a restaurant in Havana: someone came to tell him that Fidel would receive him that day at 5 p.m., so they would come to pick him up in a little while. Two days later, Fidel wrote about their one-hour-and-forty-minute-long meeting and sang the praises of a paper Atilio had presented in a conference of economists. At a later date, Mr. Boron gave Clarín unheard-of details about Castro’s daily life and the conversation they had in a place hitherto undisclosed.

“Truth is, I thought I would see a disabled person, but what I found was quite the opposite: he had a very good color and muscle tone, which I could check for myself in his handshake and hug when we said goodbye to each other”, Boron recalls. It was a summer afternoon, and Fidel was wearing the typical uniform of Cuban athletes, except for the short pants that revealed “very strong legs, a sign that he’s following his therapist’s instructions to the letter. He looks very bright”.

Fidel is not at a clinic, but in a house fitted with medical equipment for emergencies and facilities to move around and work out, and even a small pool where he can swim. He receives few visitors, his contacts with officials limited to “one or two meetings with Raúl”. You don’t see many people working in the house; he’s the one who seems to be working hard as befits “a soldier in the Battle of Ideas” and very happy and relaxed for not being in power.

We met in a living room where there was a desk, a run-of-the-mill PC, no cell phone, and the folders with clippings he’s always kept near since he was President. Boron also noticed a number of blue notebooks, organized by topic, where Fidel writes his reflections. And what about the voice of the great speaker who would talk to his audience for hours on end? “He’s never been one for speaking in a loud voice, on the contrary: he spoke slowly, still his usual self, a Fidel who chews on his every syllable”, Boron assured, adding that Fidel drank nothing nor was ever interrupted to take any medicine.

Always on top of current events, in the days of Darwin’s anniversary Castro reads his work while devouring what text on nanotechnology he can get his hands on. The chat with Boron centered on the economic crisis, and Fidel said he was worried about what he believes its great impact on the region will be like. “He thinks the continent’s certain shift to the left in the last few years will be compromised. Fidel understands the circumstances very well and fears the right will have a new lease on life”, he explained.

Did you talk about President Kirchner’s visit?

Yes, and he said to be quite impressed by how energetically she defends her positions. We also talked about the problems in the countryside, and he was shocked at the way it happened and as much concerned about the consequences as he was about other issues, for instance, Paraguay, as he believes President Lugo has many obstacles in his path.

Did you talk about the United States?

I’ve got the feeling he has taken a certain liking to Obama, but without building his hopes up too much. He said, “Obama will soon learn that the Presidency is one thing, but the Empire is another matter altogether”.

Your meeting took place at the end of a very hectic week in Cuba when changes were made in the government…

He started to talk about that and nothing else, going into greater detail about what he had already said that the enemy outside had built up their hopes with these officials, but it was made clear that what he meant was that Cuba’s enemies had raised their hopes over them. He mentioned they had made mistakes, sometimes because of excessive political ambition or personal impatience…

To get an idea of Fidel’s condition –keeping in mind that he’s almost 83– Boron points out that he can walk without anybody’s help and had even taken a stroll around the surrounding area a few weeks ago, alone and under no escort, to buy a newspaper. He was standing in line like any other Cuban and, they say, a woman recognized him and a small urban tsunami of emotions broke out in that Cuban neighborhood.

Woman and Violence

Women and Violence: A Community Health Problem?

By Alexis Culay Pérez, Félix Santana Suárez, Reynaldo Rodríguez Ferra and Carlos Pérez Alonso

SOURCE: Rev Cubana Med Gen Integr 2000;16(5):450-4

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

ABSTRACT

A descriptive horizontal study was carried out to learn the behavior of violence against women in the micro-district “Ignacio Agramonte”, of the “Tula Aerie” Policlinic in Camagüey. The period studied was from August 1st, 1997 to January 31st, 1998. From a total of 1088 women between the ages of 15-49, 310 were chosen to conduct a survey. The size of the survey was calculated using the well known statistical program EPIDAT. The results of the survey showed that 226 women reported some type of violence. This is 72,9% of the women interviewed. Psychological violence was reported by half the women, sexual violence by a third and physical violence was the least reported. The majority of women who reported violence were 30-39 year-old women with high school education. The great majority of the women victimized didn’t request professional help.

Gaceta Médica Espirituana 2008; 10(2)

Original paper

Medical Faculty “Dr. Faustino Pérez Hernández”

Family violence and adolescence

By Dra. Help Walls García1, Dra. Anabel González Muro2, Dr. Jorge Luis Toledo Prado3, Dr. Ernesto Calderón González4, Dra. Yurien Negrín Calvo5

1 First grade Specialist in Child Psychiatry. Adjutant Professor, Resident MGI

2 First grade Specialist in General Psychiatry. Adjutant Professor

3 First grade Specialist in General Psychiatry

4 First grade Specialist in MGI 5

A CubaNews translation by Giselle Gil

Edited by Walter Lippmann

ABSTRACT

Due to frequent reports of family violence against adolescents received at Clinic No.29 of the Sancti Spíritus Area Mental Health Community Center a research was carried out. The main objective of this study was to describe some of the characteristics of family violence. A horizontal descriptive study was made which included 63 adolescents between the ages of 10-18. We calculated the violence frequency as well as that of age and sex, abuse types, parent-child relations to the victim, symptoms associated with abuse and if the family is conscious of this violence. Results showed a high percent of family violence towards girls and towards children in the 13-15 year old group. Violence was found to be mostly psychological rather than physical. We also found mothers are more violent and that low self esteem and aggressiveness are the most common symptoms. Only a low percent of the families were aware of being violent. Based on these results we made a proposal to investigate this problem further in the different health areas. Further study will also help design community intervention strategies to eliminate or reduce this violence that affects adolescents and the rest of the family.

Is family violence, a health problem?

By Dr. Mario C. Muñiz Ferrer, Dra. Yanayna Jiménez García, Dra. Daisy Ferrer Marrero and Prof. Jorge González Pérez

A CubaNews translation by Giselle Gil

Edited by Walter Lippmann

ABSTRACT

A descriptive study of the results of the test “what I don’t like about my family” was carried out with the objective of studying family violence and how to confront it in a health area. The test was applied to 147 5th and 6th grade children studying in the “Roberto Poland” School located in the “Antonio Maceo” neighborhood of the municipality of Cerro. The different types of family violence were classified and grouped by incidence frequency. Family violence prevalence was also calculated, as well as its possible relation to drinking. The results allowed us to establish that family violence is a health problem and that it is related to the intake of alcoholic beverages.

INTRODUCTION

One of the most pressing problems that humanity faces in the XXI century is violence. We live in a world in which violence has become the most common way of solving conflicts. Today it is a social problem of great magnitude that systematically affects millions of people in the whole planet in the most diverse environments, without distinction of country, race, age, sex or social class.

Psychological gender violence is a covert form of aggression and coercion. Because its consequences are neither easily seen nor verified, and because it is difficult to detect, it is more and more used. Its use frequently reflects the power relationships that place the masculine as axis of all experience, including those that take place inside the family environment.1

Psychological gender violence expressed in the family environment acquires different shades depending on the context in which it takes place. In a rural environment, we generally find families with specific characteristics such as low schooling, resistance to change, inadequate confrontation and communication styles. All this favors the stronger persistence of patterns belonging to a patriarchal culture in this area rather than in urban areas, and therefore, women become victims, especially of violence.2

Cuba has a large population in urban as well as in rural areas, and so doesn’t escape from this reality (that of feminine victimización), even when our social system contributes decisively to stop many of the factors that favor violence against women. Also, we have propitiated substantial modifications of the place and role of the family as a fundamental cell of society. But, even today, we haven’t achieved a radical reorganization of the patriarchal features present in the national identity or on socializing agents like family.

The Novel of His Memories

The Novel of His Memories

Author: Fidel Castro Ruz

17 de abril de 2014 21:33:15

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

SOURCE: Granma Internacional. 08/12/02 page 8

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

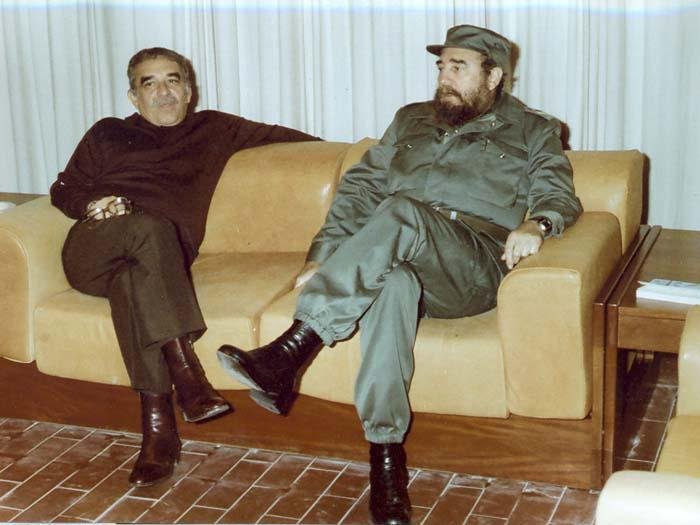

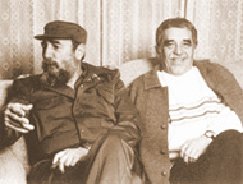

Gabo and I were in the city of Bogotá on the sad day of April 9, 1948 when [Colombian Liberal leader and presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer] Gaitán was killed. We were both 21-year-old Law students and witness to the same events. Or at least that’s what we thought, because neither of us had heard of the other. We were complete strangers, even to ourselves.

Almost half a century later, Gabo and I were chatting on the eve of a trip to Birán, the place in eastern Cuba where I was born in the early morning of August 13, 1926. Our meeting had the hallmarks of those intimate, family-like occasions when you swap reminiscences and fond memories in a warm atmosphere that we shared with a group of Gabo’s friends and some of my fellow leaders of the Revolution.

That evening I went over the images engraved in my mind: ‘Gaitán is dead!’, were the words on everyone’s lips that April 9 in Bogotá, where I was together with a number of other young Cubans to organize a Conference of Latin American students. Baffled and stock-still, I gazed at a crowd of people who were dragging the killer along the streets while others set fire to stores, office buildings, movie theaters and tenement houses, and still others were carrying pianos and cupboards on their shoulders. I could hear the sound of glass being shattered and posters being torn. From street corners, balconies full of flowers and smoldering buildings further away, voices shouted in frustration and grief. A man was venting his anger by banging his fists on a typewriter, and to spare him the bother of such a colossal, unusual effort I took it away from him and threw it hard against the cement floor, where it smashed into pieces. Gabo was listening as I spoke, probably taking my words as proof of his assertion that very few Latin American and Caribbean writers have ever needed to invent anything because here fact is stranger than fiction, so maybe his biggest problem has been how to make his own reality credible. The main thing is that, near the end of my story, I was surprised to hear that Gabo had been there too, a coincidence I found revealing in that we had perhaps walked down the same streets and lived through the same frightening, astonishing and urging experiences that made me be a part of that stormy sea of people who suddenly came down the surrounding hills. So I shot the question with my chronic curiosity. “And what were you doing during the Bogotazo[1]?” Unruffled, entrenched in his remarkable, lively, unruly and exceptional imagination, he smiled at me and replied with the clever, emphatic spontaneity of his metaphors: “Fidel, I was that man with the typewriter”.

I have known Gabo for a very long time, and we may have first met at any moment or place of his luxuriant poetic geography. As he admitted himself, he has on his conscience that he had initiated me into, and kept me up-to-date on, “the addiction to speed-reading bestsellers as a purification method against official documents”, to which we should add that he’s responsible for convincing me not only that I would like to be a writer in my next reincarnation, but also that I would like to write like Gabriel García Márquez, gifted as he is with a headstrong attention to detail on which he builds, as if it were the philosopher’s stone, all the credibility of his dazzling exaggerations. He even said once that he saw me eat eighteen scoops of ice-cream at one sitting, something that I denied emphatically, as you might expect.

Then I remembered a time when, after reading the preliminary text to Del amor y otros demonios (Love and other demons) –where a man rides his eleven-month-old horse– I suggested the author: “Look, Gabo, put two or three more years on that horse, because at that age this one’s still a foal”. Later on I read the printed novel, and what comes to mind is a passage where Abrenuncio Sa Pereira Cao, whom Gabo describes as the most notable and controversial physician in the city of Cartagena de Indias at the time the story is set, is sitting on a stone by the side of the road, crying next to his dead horse, who would have been a 100 years old come October but whose heart had stopped as they were coming down a steep descent. Gabo, as expected, turned the animal’s age into an exceptional circumstance, an incredible happenstance of indisputable truthfulness.

His books are irrefutable evidence of his sensitivity and steadfast adherence to his roots, the inspiration he draws from Latin America, his loyalty to the truth, and his progressive thoughts.

We share an outrageous theory, likely to sound godless to academics and men of letters, about the relative nature of words, and I stick to it with as much passion as I feel for dictionaries, especially one that he gave me for my 70th birthday, a real gem in which every definition is followed by famous quotations from Spanish American writers as examples of the proper way to use your vocabulary. Besides, as a public man obliged to write speeches and recount events, I share with this renowned author what you may call an endless obsessions: we both take great pleasure in looking for the exact word until the phrase turns out the way we want, faithful to the feeling or idea we wish to convey and always from the premise that it can be improved. I admire him most of all when he simply invents a new word if the right one doesn’t exist. How envious I am of such liberty!

Now Gabo writes about Gabo: he has published his autobiography, that is, the novel of his memories, a work that I believe stems from nostalgia for the four o’clock thunderclap, the instant full of bolts of lightning and magic that his mother Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguarán missed when she was far from Aracataca, the unpaved hamlet of never-ending downpours, alchemists, telegraph, and the stormy sensational love affairs that would impregnate Macondo, the small town in the pages of one hundred lonely years, with all of Aracataca’s dust and charm. As a token of our old and warm friendship, Gabo usually sends me his manuscripts, much as he sends his rough drafts to other dear friends of his as a gesture of kindness and unaffectedness. This time, he delivers himself with honesty, innocence and energy, the qualities that disclose what he really is: a man with the goodness of a child and infinite talent, a man of tomorrow whom we thank for the things he’s been through and for having lived to tell the tale.

[1] The Bogotazo refers to the massive riots that followed the assassination of Gaitán.

Today’s youth… lost?

Today’s youth… lost?

Author: Leticia Martínez Hernández

May 22, 2009

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

I admit it: it bothers me when my generation is called into question, not taken seriously and, worse yet, branded a lost cause, a very good reason to annoy the most even-tempered of souls, of which I am one. Is the word ‘lost’ by any chance synonymous with irreverent, revolutionary, nonconformist, impetuous, determined…? I don’t think so.

I admit it: it bothers me when my generation is called into question, not taken seriously and, worse yet, branded a lost cause, a very good reason to annoy the most even-tempered of souls, of which I am one. Is the word ‘lost’ by any chance synonymous with irreverent, revolutionary, nonconformist, impetuous, determined…? I don’t think so.

A few days ago I took a bus, a bag hanging on my shoulder. Just by chance I found an empty seat beside a boy wearing the latest styles, tattoos and earphones included, who was also carrying something.

As chance would have it, we got off at the same stop, and I felt a great sense of relief when he insisted on helping me down the steps of the rear door with my load, his own notwithstanding. Like a harbinger of doom, the gloomy phrase suddenly came to me, as did memories of so many other boys and girls in their twenties who would leave more than one skeptic at a loss for words, and some who do give their nitpickers cause to complain.

Should we call lost those youths who stormed into the Isle of Youth, Pinar del Río, Holguín, Las Tunas and other Cuban provinces to share the pain of –and ease the burden on– the victims when the heavy rains and strong winds laid into Cuba last September? Or those who for the first time got their hands dirty trying one way or another to reap some benefit from the wounded land? I remember some of tem doing their best to make sad children laugh while their own family had no roof over their heads.

And the thousands of young Cubans who keep our education system going today, are they also the target of those fire-and-brimstone statements? Do the skeptic know anything about the nights those youths spend preparing their lessons while others their age are having great fun at a party; about how nervous they are on their first day in front of a class; about how they puff up with pride to be teachers even before their twentieth birthday; about the overwhelming burden that mistrust places on their shoulders?

Would the word ‘lost’ apply to those boys and girls who ache for their faraway loves as they stand day and night on our coastal reef to watch over every stretch of this country? If they only knew about Lester and his stubborn patrolling along some far-flung beach of Guantánamo province, or about Javier’s great responsibility for a radar who does nothing but sweep the sea surface!

A colleague heard of the paper I work for and asked my age right away: “And at 25 you’re already writing for Granma?” I had to summon up my patience for a long while –someone else said once that we were being ripened with carbide– before I told him of so many others like me he could find walking the halls of the official organ of the Communist Party of Cuba, where they spend countless hours waiting for closing time or hunting for the best thesis to finish a report while listening to [Cuban folk singer] Silvio, taking a few dance steps or exchanging jokes.

Have the doubters forgotten the exploits of those beard-wearing boys who cut their way through the bush in the Sierra Maestra Mountains and then raided our cities to disrupt the existing order inside Cuba and out? If a brilliant man like Fidel has always trusted in our youth’s creative strength, why are there others who allow themselves the luxury of casting a shadow over them? We could fill endless pages with stories of young people who are underestimated on arguments as flimsy as their lack of experience. How different everything would be had the pioneers of this Revolution waited for the lazy, slippery experience…!

It’s true that things are different now and it’s no longer our role to be heroes in the crossfire, but the bullets now aimed at our heads are far more dangerous. Today’s average youth must place limits on their aspirations, chances of personal fulfillment and even opportunities to have fun at the same time as they are showered with deceitful canons designed to convince them there’s a better way of life outside our country. And despite the few who may fall for the swan song and others who allow despondency to get the better of them, millions remain who refuse to give in and still fight for their homeland’s future.

What do they mean then by saying that youth, my youth, is hopeless? That we wear provocative and stylish clothes, live noisily, say what we think without a second thought, dream of possible and impossible things, dare to take on responsibilities we have no idea we can ever fulfill, never wait until tomorrow to pledge our commitment to the future… ? If these are the answers, then not only are we lost, we don’t want to be found.

All The Absences/About Exile and Other Abductions

All The Absences/About Exile and Other Abductions

Or It Fits If It Fits

By Kobo Abe

The Woman in the Sand

Loneliness is a Thirst that Illusion Cannot Satisfy

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Synopsis:

Ely, the wife of the “Godfather of Havana” undertakes the odyssey of leaving Cuba with her family at the start of the 1980s. An almost complete spectrum of the psychology of Cubans who have decided to leave (or not) parades through her home: marriages to former political prisoners; the months during the Mariel boatlift; the discrimination and ignorance that accompanies her; the opportunism; the avarice; the betrayal; the selfishness; and, on top of all that, the implosive nature of familial love, offered friendship, solidarity, genuine apathy, spontaneity, and genuine human interaction. The best, the worst and the moderate aspects of Cuban idiosyncrasy overwhelm Ely’s life, and are reflected in her family, friends and acquaintances, who parade through a text that is constructed with every page. The story of the internal and external exile of these characters incites us to change the gestalt, to identify with the whole as well as its parts; it constitutes a swipe to those who emigrate, about the challenges and the price of existence regardless of circumstance, and how the fruits of that existence cannot calm the strange thirst that illusion is unable to quench, according to the preface written by Japanese author Kobo Abe at the beginning of this novel.

You must be logged in to post a comment.