The Novel of His Memories

Author: Fidel Castro Ruz

17 de abril de 2014 21:33:15

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

SOURCE: Granma Internacional. 08/12/02 page 8

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

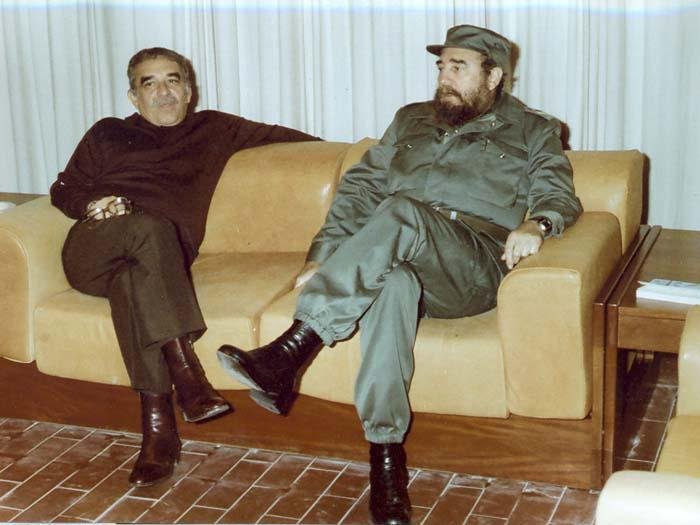

Gabo and I were in the city of Bogotá on the sad day of April 9, 1948 when [Colombian Liberal leader and presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer] Gaitán was killed. We were both 21-year-old Law students and witness to the same events. Or at least that’s what we thought, because neither of us had heard of the other. We were complete strangers, even to ourselves.

Almost half a century later, Gabo and I were chatting on the eve of a trip to Birán, the place in eastern Cuba where I was born in the early morning of August 13, 1926. Our meeting had the hallmarks of those intimate, family-like occasions when you swap reminiscences and fond memories in a warm atmosphere that we shared with a group of Gabo’s friends and some of my fellow leaders of the Revolution.

That evening I went over the images engraved in my mind: ‘Gaitán is dead!’, were the words on everyone’s lips that April 9 in Bogotá, where I was together with a number of other young Cubans to organize a Conference of Latin American students. Baffled and stock-still, I gazed at a crowd of people who were dragging the killer along the streets while others set fire to stores, office buildings, movie theaters and tenement houses, and still others were carrying pianos and cupboards on their shoulders. I could hear the sound of glass being shattered and posters being torn. From street corners, balconies full of flowers and smoldering buildings further away, voices shouted in frustration and grief. A man was venting his anger by banging his fists on a typewriter, and to spare him the bother of such a colossal, unusual effort I took it away from him and threw it hard against the cement floor, where it smashed into pieces. Gabo was listening as I spoke, probably taking my words as proof of his assertion that very few Latin American and Caribbean writers have ever needed to invent anything because here fact is stranger than fiction, so maybe his biggest problem has been how to make his own reality credible. The main thing is that, near the end of my story, I was surprised to hear that Gabo had been there too, a coincidence I found revealing in that we had perhaps walked down the same streets and lived through the same frightening, astonishing and urging experiences that made me be a part of that stormy sea of people who suddenly came down the surrounding hills. So I shot the question with my chronic curiosity. “And what were you doing during the Bogotazo[1]?” Unruffled, entrenched in his remarkable, lively, unruly and exceptional imagination, he smiled at me and replied with the clever, emphatic spontaneity of his metaphors: “Fidel, I was that man with the typewriter”.

I have known Gabo for a very long time, and we may have first met at any moment or place of his luxuriant poetic geography. As he admitted himself, he has on his conscience that he had initiated me into, and kept me up-to-date on, “the addiction to speed-reading bestsellers as a purification method against official documents”, to which we should add that he’s responsible for convincing me not only that I would like to be a writer in my next reincarnation, but also that I would like to write like Gabriel García Márquez, gifted as he is with a headstrong attention to detail on which he builds, as if it were the philosopher’s stone, all the credibility of his dazzling exaggerations. He even said once that he saw me eat eighteen scoops of ice-cream at one sitting, something that I denied emphatically, as you might expect.

Then I remembered a time when, after reading the preliminary text to Del amor y otros demonios (Love and other demons) –where a man rides his eleven-month-old horse– I suggested the author: “Look, Gabo, put two or three more years on that horse, because at that age this one’s still a foal”. Later on I read the printed novel, and what comes to mind is a passage where Abrenuncio Sa Pereira Cao, whom Gabo describes as the most notable and controversial physician in the city of Cartagena de Indias at the time the story is set, is sitting on a stone by the side of the road, crying next to his dead horse, who would have been a 100 years old come October but whose heart had stopped as they were coming down a steep descent. Gabo, as expected, turned the animal’s age into an exceptional circumstance, an incredible happenstance of indisputable truthfulness.

His books are irrefutable evidence of his sensitivity and steadfast adherence to his roots, the inspiration he draws from Latin America, his loyalty to the truth, and his progressive thoughts.

We share an outrageous theory, likely to sound godless to academics and men of letters, about the relative nature of words, and I stick to it with as much passion as I feel for dictionaries, especially one that he gave me for my 70th birthday, a real gem in which every definition is followed by famous quotations from Spanish American writers as examples of the proper way to use your vocabulary. Besides, as a public man obliged to write speeches and recount events, I share with this renowned author what you may call an endless obsessions: we both take great pleasure in looking for the exact word until the phrase turns out the way we want, faithful to the feeling or idea we wish to convey and always from the premise that it can be improved. I admire him most of all when he simply invents a new word if the right one doesn’t exist. How envious I am of such liberty!

Now Gabo writes about Gabo: he has published his autobiography, that is, the novel of his memories, a work that I believe stems from nostalgia for the four o’clock thunderclap, the instant full of bolts of lightning and magic that his mother Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguarán missed when she was far from Aracataca, the unpaved hamlet of never-ending downpours, alchemists, telegraph, and the stormy sensational love affairs that would impregnate Macondo, the small town in the pages of one hundred lonely years, with all of Aracataca’s dust and charm. As a token of our old and warm friendship, Gabo usually sends me his manuscripts, much as he sends his rough drafts to other dear friends of his as a gesture of kindness and unaffectedness. This time, he delivers himself with honesty, innocence and energy, the qualities that disclose what he really is: a man with the goodness of a child and infinite talent, a man of tomorrow whom we thank for the things he’s been through and for having lived to tell the tale.

[1] The Bogotazo refers to the massive riots that followed the assassination of Gaitán.

You must be logged in to post a comment.