Trotsky 8

Fidel Castro on Trotsky

IGNACIO RAMONET: It’s been said that Che even had some Trotskyite sympathies. Did you see that in him at that point?

FIDEL CASTRO: No, no. Let me tell you, really, what Che was like. Che already had, as I’ve said, a political education. He had come naturally to read a number of books on the theories of Marx, Engels and Lenin . . . He was a Marxist. I never heard him talk about Trotsky. He defended Marx, he defended Lenin, and be attacked Stalin — or rather, he criticized the cult of personality, Stalin’s errors … But I never heard him speak, really, about Trotsky. He was a Leninist and, to a degree, he even recognized some merits in Stalin — you know, industrialization, some of those things.

I, deep inside, was more critical of Stalin [than Che was], because of some of his mistakes. He was to blame, in my view, for the invasion of the USSR in 1941 by Hitler’s powerful war machine, without the Soviet forces ever hearing a call to arms. Stalin also committed serious errors — everyone knows about his abuse of force, the repression, and his personal characteristics, the cult of personality. But yet he also showed tremendous merit in industrializing the country, in moving the military industry to Siberia — those were decisive factors in the world’s fight against Nazism.

So, when I analyze it, I weigh his merits and also his great errors, and one of those was when he purged the Red Army due to Nazi misinformation — that weakened the USSR militarily on the very eve of the Fascist attack.

FIDEL CASTRO, My Life. By Fidel Castro and Ignacio Ramonet, p. 181.

Scribner, 2008

===================================================

On another occasion you said to me that there was no longer any ‘model’ in the sphere of politics and that today no one knew very well what the concept ‘Socialism’ meant. You were telling me that at a meeting of the São Paulo Forum that was held in Havana, which all the Latin American Lefts attended, you, the participants, had to reach an agreement not to speak the word ‘Socialism’ because it’s a word that ‘divides’.

Look — what is Marxism? What is Socialism? They’re not well defined. In the first place, the only political economy that exists is the capitalist one, but the capitalist one of Adam Smith.’ So here we are making Socialism sometimes with those categories adopted from capitalism, which is one of the greatest concerns we have. Because if you use the categories of capitalism as an instrument in the construction of Socialism, you force all the corporations to compete with each other, and criminal, thieving corporations spring up, pirates that buy here and buy there. There needs to be a very profound study [of this].

Che once got involved in a tremendous controversy about the consequences of using budget financing versus self-financing. We talked about that.’ As a government minister, he had studied the organization of several great monopolies, and they used budget financing. The USSR used another method: self-financing. And he had strong opinions about that.’

Marx made just one slight attempt, in the Critique of the Gotha Programme,’ to try to define what Socialism would be like, because he was a man of too much wisdom, too much intelligence, too great a sense of realism to think that one could write a utopia of what Socialism would be like. The problem was the interpretation of the doctrines, and there have been ‘a lot of interpretations. That was why the progressives were divided for so long, and that’s the reason behind the controversies between anarchists and socialists, the problems after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 between the Trotskyites and the Stalinists, or, we might say, [in deference to] the people on one or another side of those great controversies, the ideological schism between the two great leaders. The more intellectual of the two was, without a doubt, Trotsky.

Stalin was more a practical leader — he was a conspirator, not a theorist, even though once in a while, later, he would try to turn theorist … I remember some booklets that were passed around in which Stalin tried to explain the essence of ‘dialectical ‘materialism’, and he used the example of water. They tried to make Stalin into a theorist. He was an organizer of great ability, I think he was a revolutionary — I don’t think he was ever at the service of the tsar, ever. But then he committed those errors that we all know about — the repression, the purges, all that.

Lenin was the genius; he died relatively young, but he would have been able to do so much had he lived. Theory doesn’t always help. In the period during which the Socialist state was being built, Lenin desperately applied-beginning in 1921 — the NEP,” the new economic policy . . . We’ve talked about that, and I told you that Che himself didn’t like the NEP.

Lenin had a truly ingenious idea: build capitalism under a dictatorship of the proletariat. Remember that what the great powers wanted to do was destroy the Bolshevik Revolution; everybody attacked it. One mustn’t forget the history of the destruction they caused in that underdeveloped country; Russia was the least-developed country in Europe, and of course Lenin, following Marx’s formulation, thought that the revolution couldn’t occur in a single country, that it had to occur simultaneously in the most highly industrialized countries, on the basis of a great awakening of the forces of production.

So the great dilemma, after that first revolution took place in Russia, was what path to follow. When the revolutionary movement failed in the rest of Europe, Lenin had no alternative: he had to build Socialism in a single country: Russia. Imagine the construction of Socialism in that country with an 80 per cent illiteracy rate and a situation in which they had to defend themselves against everybody that was attacking them, and in which the main intellectuals, the men and women with the most knowledge, had fled or were executed. You see?

It was a pretty terrible time, with intense debates.

There were many, many controversies. Lenin had died by then. In my opinion, during the ten years of the NEP the Soviet Union wasted time setting up agricultural cooperatives. Since individual production yielded the maximum of what could be produced under those conditions, collectivization was precipitate. In Cuba there were always, out in the country, over 100,000 individual landowners. The first thing we did in 1959 was give everyone who was leasing land or working as sharecroppers the property they were working on.

FIDEL CASTRO, My Life. By Fidel Castro and Ignacio Ramonet, p. 387-389.

Scribner, 2008

The Lesson of the Soviet Union

The Lesson of the Soviet Union is That the Bureaucracy Chooses Capitalist Restoration

By: Wilder Pérez Varona / Interview with Eric Toussaint.

By: Wilder Pérez Varona / Interview with Eric Toussaint.

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

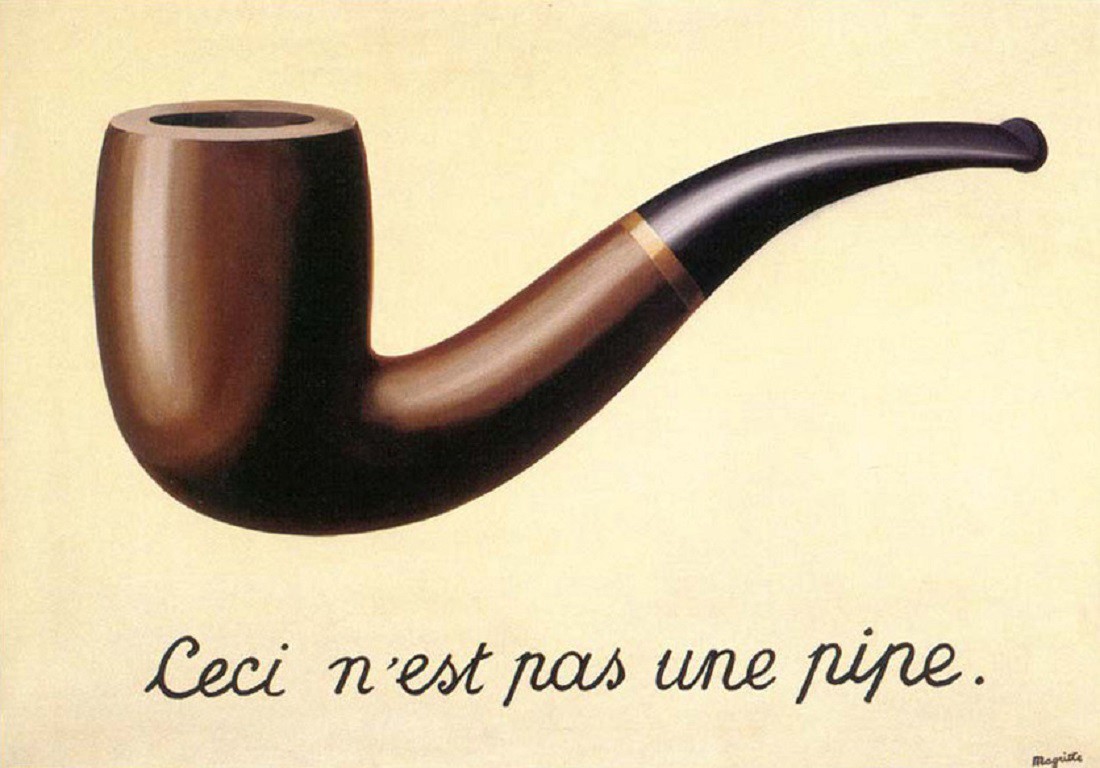

“The betrayal of images” (1929) – René Magritte / “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (This is not a pipe)

Wilder Pérez Varona (WPV): The first question I want to ask you is in relation to the issue of bureaucracy.

Before 1917 the subject of the socialist transition is one thing: since the Revolution of 1848, the Paris Commune (which is a fundamental episode, but of ephemeral character) was always limited rather to questions of theory, principles, projection (we know that Marx and Engels were reluctant to be very descriptive with respect to those projections). The Revolution of 1917 placed this problematic of transition in other terms, in another plane; in a plane that has fundamental practical elements. One of them has to do with the issue of bureaucracy, which appeared gradually throughout the 1920s. On this question of bureaucracy as it was elaborated in those circumstances, how do you define that function of bureaucracy by giving it a role as such a relevant actor, at the level of the class triad: working class/peasantry and bourgeoisie? Why that important place? I would also like you to express yourself on the distinction of “class”. You are very careful to talk about bureaucracy as a class; however, other authors do.

Eric Toussaint (ET): Well, it is clear that the experience of Russia and then the Soviet Union is, I would say, almost the second experience of attempting to seize power in order to begin a transition of rupture with capitalism. The first experience is the Paris Commune, which lasted three months in 1871, limited at the territorial level to Paris as such, isolated from French territory and attacked. So it is clear that revolutionaries like Lenin, Trotsky, and other leaders of the Bolshevik Party had no point of comparison with other experiences and conceived of the problem of transition, as I mentioned in my presentation,[2] in a triangular way, that is, the need for an alliance between proletariat and peasantry to defeat the bourgeoisie and Imperialism, and to resist imperialist aggression after the seizure of power.

And the issue of something like the subsistence and weight of the tsarist state apparatus, which had a bureaucracy, and then the struggle against bureaucracy and bureaucratism was rather conceived at first as a struggle against something that was part of the past, of the tsarist heritage. Within the framework of the development of the transition, from the early years, both Lenin and Trotsky and others found themselves faced with a new problem and they had to start analyzing and clarifying, and so on. Lenin did not manage to elaborate, I would say, a theory of bureaucracy because he died in January 1924, but what is absolutely true in Lenin’s case is that he, in several extremely clear and important interventions, denounced the bureaucratic deformation of the workers state under construction. Already in the debate on trade unions in 1920-1921 he said that the workers’ state led by the Bolshevik Party had bureaucratic deformations and, therefore, the workers and their unions had to maintain some level of independence from the bureaucratically deformed workers’ state. That seems very important to me.

Another aspect in Lenin’s position of late 1922 and early 1923 is found in the critique of an institution created by the same government, called the Worker and Peasant Inspectorate, and Lenin says that this body, which has to serve in the struggle against bureaucracy and to which every citizen (proletarian or peasant) can turn and denounce bureaucratic behavior, says that this same body is totally bureaucratized. And that organism was directed by Joseph Stalin. Lenin proposes a complete reform of that organism in which there were twelve thousand civil servants. At that time the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate, which supposedly fought against bureaucratism, actually helped bureaucratization and aggravated the problem in which the bureaucratically deformed workers’ state already found itself. It should also be mentioned, because it is little known, that Stalin did everything necessary to make it disappear at the public level or even to prevent public knowledge of Lenin’s letters saying that Stalin should be removed from the post of Party Secretary General.

That’s what I mean about Lenin. Then I said in my presentation that the problem of transition to socialism is not limited to the bourgeois/proletariat/peasant triangle, but that there was a fourth actor that is bureaucracy, and bureaucracy is not limited to being a legacy of the past, in the case of Russia from the tsarist past, but the bureaucracy itself emerges within the transition process and consolidates itself as an actor that is progressively gaining confidence, in the course of the transition, of its interests, and its interests (in the case of the Russian experience) began to distance themselves from the interests of both the proletariat and the peasantry and, in some way, the bourgeoisie. That is, the bureaucracy did not consciously aim at the restoration of capitalism and the power of the bourgeoisie. The bureaucracy was not, I would say, an aid to capitalist restoration, but pursued its own interests and in that case its own interests were to have the monopoly of political power and from the apparatus of the state to direct, lead the process and, in some way, transform the party into an instrument of bureaucracy, transform the unions into a transmission belt of bureaucratic power to the rank and file and have an economic development in which the proletariat and peasantry cannot really act in defense of their own interests, but begin to be (in the case of Russia) exploited by the bureaucracy. The bureaucracy headed by Stalin promoted a level not only of authoritarianism, but also of dictatorship over the working people both in the rural world and in industrial enterprises or other state-controlled economic sectors.

But of course, bureaucracy does not generate a new ideology. The bureaucracy is not going to vindicate bourgeois ideology because it is officially being fought against. Then the bureaucracy, in general, took the “official” socialist program as an ideological dress and program, and speaks in the name of deepening the process of building a socialist society because the bureaucracy does not generate an ideology of its own, which would imply distancing itself from the official program of the Revolution. Somehow the bureaucracy operates in a hidden way with its own interests, and can destroy both organizations and people who really want a deepening of the process, can destroy them using officially the defense of socialism.

In the course of the 1920s, leaders like Christian Rakovsky, a Bolshevik leader, revolutionary, important, and then Trotsky, began to understand the specificity of the bureaucracy. It took years to really understand what it was all about and it is with the 1935 elaboration of The Revolution Betrayed that Trotsky comes to a complete elaboration of the analysis of what is a bureaucratically not only deformed, but degenerated state. That is to say, the ties that the power of the Soviet Union had with the Revolution in 1935 and the first years had completely distanced themselves. There remained a society that was no more capitalist, there were no capitalists in the Soviet Union, but the process towards socialism, which implies democracy, workers’ control, forms of self-management, independent and free cultural creation, the possibility of debate among revolutionaries, of open debate, had been totally degraded and destroyed and there were no more these spaces. That is why Trotsky called for a political revolution saying, it is not so much a social revolution against property relations in the production sector, it is not an anti-capitalist revolution that has social features. A political revolution is necessary to allow the proletariat, the peasantry, all wealth-producing workers, and the people in general, to regain political power. Hence the term “political revolution”. And hence demands that are above all political: freedom of expression, freedom of organization, workers’ control, self-management, pluralism of parties respecting the constitution.

Trotsky also launched a debate on the extension or not of the revolution, what is it for, what is the Communist International for? Trotsky advocated the extension of the revolution to the international level and for permanent revolution. It is necessary to remember that a Communist International had been built, the Third International founded in 1919, then led by Lenin, Trotsky, Zinoviev, Radek (Stalin at the beginning of the Communist International did not really have any presence, he was not an internationally known leader as the head of the process of extension of the revolution). It is only when Stalin succeeds in expelling Trotsky from the Communist Party in 1927 and expelling him from the country in 1929 that he begins to fully lead the Stalinized Third International and puts that International at the service of the interests of the very bureaucracy of the Soviet Union, and no longer to really extend the revolution internationally.

WPV: And although the bureaucracy does not generate an ideology of its own, nevertheless in practice (from the historical evolution of the so-called “real socialisms”), it actually managed the capitalist restoration in those countries. You also pointed out that they exploited the classes of peasants and workers, of producers in general, how then do you distinguish that bureaucratic management and exploitation with respect to a capitalist exploitation; between the one carried out by the bureaucracy and the bourgeoisie?

ET: It is that during that long period of bureaucratic power, that same bureaucracy considers that the conditions are not yet met to pass to a process in which, as a social layer is transformed into a class for the private accumulation of wealth. What is, I would say, typical of the capitalist class: a private accumulation of wealth.

But at the same time, the lesson of the Soviet Union is that, after all, that bureaucracy that is not building a new kind of system chooses capitalist restoration and the bureaucrats themselves become capitalists. In other words, they somehow cross the border as a social layer and transform themselves into a capitalist class. As bureaucrats, before capitalist restoration, they can accumulate levels of wealth, privileges, and so on, but their privileges come from the management of a society in which large private property, capitalist property, does not exist or is totally marginal and that does not have a great future, but that social layer (or a part, a fraction of the social layer) may last for decades and at any given time decide that it is time to restore capitalism. This is what happened in the late 1980s and early 1990s in the Soviet Union. I personally think that’s what happened in China from the Reforms of Deng Xiaoping in the late 1980s as well, and in Vietnam we also had that evolution.

Of course, the historical perspective could have been of another kind, that is, a capacity of the producers (proletariat, peasantry or intellectual worker) to regain power from a political revolution, but that did not happen and it was not Gorbachev’s perspective. He spoke of Glasnost, in terms of liberation from political debate, but Perestroika was to introduce reforms in favor of the progressive capitalist restoration. So that is the great challenge of the transitional society: how to deal with the problem of bureaucratization and the consolidation of the bureaucracy as the leading and dominant social layer, also when the country is isolated, and has problems to really succeed in increasing production, increasing its endogenous development, and responding to the needs of the workers.

WPV: To a large extent all the reforms of the 1980s were also made with the slogan of the democratization of bureaucratized socialism. However, the history of the relationship between Socialism and Democracy has involved many conflicts, many contradictions, many misunderstandings…

ET: It is extremely complicated because (you know perfectly well in Cuba) the transition to socialism leads Imperialism to a policy of aggression that can take various forms. Therefore, this aggressive attitude makes it complicated to have total freedom of expression within the framework of the process. The same aggression produces reactions of limitation of expression, and so on; but of course, at a given moment the bureaucracy uses the external threat to maintain a limitation of the political debate because it is not really in the people’s interest to have a political debate that could weaken the bureaucratic control over society.

So, the issue is very complex. I would say that it is clear that we have to face an external aggression that can take various forms, but we cannot, under this situation of aggression, limit in an exaggerated way the possibility of expression, of organization, of protests, and so on.

In my presentation, I made reference to Rosa Luxemburg, who totally supported the Bolshevik Revolution. As you know, she was assassinated in January 1919 under orders from German Social Democratic ministers, but in 1918 she wrote several letters to the Bolsheviks, which she made public, to say “comrades Lenin, Trotsky, beware of the measures you are taking to limit political freedoms,” etc., because that can lead to a process that is going to be deadly for the Soviet Revolution. I would say, what is the balance that we must find in the transition, and at that level we must also evaluate the attitude of Lenin, Trotsky, and others… what happened to Kronstadt, that rebellion of sailors near Petrograd; what happened to the secret police (the NKVD or Cheka), which had the possibility of extrajudicial execution processes, of imprisonment of opponents… the question of trade unions; it is clear that we have to be able to analyze this.

It is also important for us to analyze what happened in a country like Cuba. The whole libertarian issue in the 1960s in Cuba, then followed by the increase in the negative influence of the USSR bureaucracy from the economic difficulties after the 1970 harvest, and then analyze and also draw lessons from the Cuban experience. It is also very important.

WPV: Of course, we have to analyze the processes in their particular contexts, but we also have to take into account certain limits in the prerogatives of the revolutionary government itself, let’s say, to assume the direction and control of the process. In this link between Socialism and Democracy, you are in favor of the limitation of democracy. In other words, it is not just Democracy, it is not the democracy that has been hegemonized by capitalist perspectives, but a limited democracy (socialist or of any other kind, a workers’ democracy).

ET: For example, for me one of the lessons of the Russian experience is the need for a multi-party system by saying that, within the framework of the transition, the existence of several parties should be allowed if they accept, respect, the socialist, working-class Constitution. In the society of transition to socialism, one cannot allow a pro-imperialist party calling for outside intervention, or supporting outside intervention, or let it freely organize, recruit and prepare a pro-imperialist strategy. But there may be different parties, which have different visions of the transition, and which can coexist; and the people must be able, thanks to their political formation and increasing it, to choose among various options. Of course, encourage debate and call for consultations on decisions to be taken.

I would also say that one of the lessons of the so-called “real socialism” societies of the twentieth century is that, and this seems fundamental to me, they must have at the economic level an important sector of private economy, small private property. The small private property of land, the small private property of workshops, restaurants, shops. The Soviet experience also had an influence on Cuba, nationalizing almost everything at any given moment, which damaged the process. I was here in 1993 when the liberation of the activity of the self-employed was announced and seemed to me to be a good measure or the peasant free markets where peasants can come to the city and sell their products. That space should have been maintained in the Soviet Union, where the forced collectivization imposed by Stalin from 1929 was a disaster, and its tremendous consequences on agriculture. That is to say, there is the question of political democracy, but also for me there must be a differentiation of statutes of producers and small private production, and small private property or private initiative must be guaranteed during the process.

In the case of China, Vietnamese and the Soviet Union, which disappeared in 1991, then the Russian Federation, Ukraine, etc., did not put limits to private property and restored the large private capitalist property. And bureaucrats or friends of the bureaucrats were transformed into oligarchs and accumulated tremendous wealth as new capitalists, even very aggressive against the workers and robbing the nation of a large part of the wealth generated by the producers.

So the debate is not just about democracy, it is also about economic reforms and the social content of economic reforms.

WPV : On the question of limits to the market, the limits to private enterprise, in these socialist experiences (including Cuba) the discussion has often turned in terms of the Plan / Market relationship. In other words, to what extent the centrally planned state must intervene, must limit, limit the expansion of the market. However, it is presupposed that there must be a central Plan; In general, it is something implicit, something that is not questioned. In relation to this, it can be assumed that the Plan thus conceived is also one of the most effective instruments available to the bureaucracy, what is your opinion on the matter?

ET: I remember discussions in Cuba about the role of the market, etc., for example, the debate that took place when Che was Minister of Industry.[3] In the 1990s discussions about the role of the market came back, I remember very well, I was invited to all the events about globalization between 1998 and 2008-2009. Fidel [Castro] participated in all the events that lasted three, four days, at the Palacio de las Convenciones with one or two thousand Cuban and foreign guests, and Fidel on several occasions asked exactly about the role of the market and the limits to be set to the market.[4].

Personally, my answer is as follows. It is fundamental to allow and support the small private initiative, the small agricultural production, which may even be a majority but small, that is, a majority of peasant families producing most of the agricultural production. It is one of the incentives to increase production and achieve food sovereignty, to also improve their standard of living thanks to increased production with the sale of more products, it is a powerful incentive to achieve a high level of production and quality because the farmer knows that if he does not produce quality products he will not be able to sell them on the market or to the state.

Therefore, I believe that at that level there were serious errors in the conduct of the agricultural policy of many so-called socialist countries, where they wanted to nationalize or impose cooperatives that were not really efficient. But, at the same time, for me, planning is fundamental and I would say that in modern economies it is even more important. Let’s imagine for a moment a socialist revolution in Europe or the United States. Planning is fundamental, how can you imagine the fight against climate change, if you are not planning to put an end to power stations with coal, oil or gas, and change it for forms of renewable energy? That has to be planned, because it is not the local communities, the families, who can make that decision, because the production of energy at this time is on a large scale. Therefore, combating climate change has a relationship with what I said about family production using organic methods of agricultural production, in order to combat climate change or to limit the effects of climate change that is already underway.

So, planning is important. The issue is how to ensure that the people, the citizens, can influence planning decisions. And there for me the answer, in some way, passes through the Internet, the media we have, Television, and so on. Several options can be presented to the people and decide, if we take such an option we can foresee that it will have such consequences on their living conditions, if we take another option it will have these negative effects; allow debate on these options, and at a given moment, that people pronounce on options that have to do with the priorities of the Five-Year Plan, for the decade, and so on.

For me, the lesson of the so-called socialist experiences of the last century lies in the fact that it was a planning led by bureaucratic apparatuses that decided what was most interesting and imposed priorities. On the contrary, it would have been necessary to discuss different options. For me, then, we must not end planning, we must democratize planning.

Precisamos una nueva opción socialista, autogestionaria, ecologista, socialista, feminista. Tenemos que abogar por esa perspectiva.

WPV: Returning, finally, to the framework of the event, which has been the opportunity to interview you, what does it mean for you to hold in Cuba this international event on the figure of Trotsky? What importance do you attach to dialoguing with Trotsky today?

ET: For me, this Trotsky conference is a very positive initiative. It is an academic conference, not a tribune of political organizations to recruit, but a discussion on many different aspects of Leon Trotsky’s elaboration, contribution and combat. During the conference, Trotsky’s struggle against the bureaucracy, the struggle for the extension of the revolution, the struggle to confront external aggression were analyzed. Trotsky was the head of the Red Army that managed to defeat counter-revolution and external aggression in 1919-1920 in Soviet Russia. Trotsky’s contributions on the problems of everyday life, his contributions on literature, culture (it was an important topic in this conference), the reality of Soviet society in the 1920s were also analyzed during the conference….

And why is it important to do it in Cuba? Because Cuba is, I would say, the only country of what were called “socialist countries” where capitalism has not been restored. There is a fundamental debate for Cuba about how, taking into account the lessons of the last century, the internal struggles in the Soviet Union between 1920 and 1930, on the one hand; and the recent experiences of capitalist restoration in Russia, in China, and in other countries, how to position themselves as Cubans, in a sovereign manner, and lead the way into the future. Of course, it is complicated because the external aggression continues. We have Trump, who is restricting the small space that had been opened during Obama’s term for Cuba, which was somewhat limited but indicated an opening. Now, with Trump, spaces are closing again. So, of course, the stakes for the Cuban people and the challenges for Cuban socialism are very important.

As an internationalist, I have always supported the Cuban Revolution, I have supported the fight against the blockade imposed on Cuba, I have bet on dialogue with Cubans. And to see that there is a space in Cuba to rethink Trotsky’s contribution, the meaning that this contribution can have in today’s debates in Cuba, is a joy for me. There are dozens of comrades here who are revolutionaries in their countries, who may have different positions, different visions of Trotskyism, there are of course, there are different visions of Marxism, different visions of Leninism, of Fidelismo, of Guevarism, there is not just one vision. There are discussions, but I can tell you that I feel the enthusiasm of comrades who have been fighting for decades and who consider this initiative in Cuba to be very positive.

Notes

1] Eric Toussaint. Doctor in Political Science from the Universities of Paris VIII and Liège. Militant internationalist. Author of several books published in Cuba: Global Crisis and Alternatives from the Perspective of the South (Editorial Ciencias sociales, 2010, http://www.cadtm.org/Crisis-global-y-alternativas-desde ), Las Finanzas contra los pueblos. La Bolsa o la Vida (Social Sciences Publishing House, 2004, http://www.cadtm.org/La-Bolsa-o-la-Vida-Las-Finanzas ), among others.

2] Refers to the paper presented at the International Colloquium dedicated to León Trostky held in Havana between May 6 and 8, 2019, which was hosted by the Benito Juárez house. See the paper: Eric Toussaint, “Lenin and Trotsky versus the bureaucracy and Stalin. Russian Revolution and Transitional Society. Spanish: http://rebelion.org/docs/256387.pdf. English: http://www.internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article4900

3] See Che Guevara, El Gran Debate Sobre la economía en Cuba, Editorial Ocean Press, 2018, 424 pages, ISBN: 978-1-925317-36-7, https://oceansur.com/catalogo/titulos/el-gran-debate-2.

4] See for example: http://www.fidelcastro.cu/es/discursos/discurso-en-la-clausura-del-v-encuentro-sobre-globalizacion-y-problemas-del-desarrollo-en.

Interview with Yunier Mena

Interview with Yunier Mena, young Cuban communist

By Ubaldo Oropeza, Centro de Estudios Socialistas Carlos Marx

May 18, 2018

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

Yunier Mena is a young Cuban student who attended the León Trotsky International Academic Event held in Havana from May 6 to 8 of this year.

Ubaldo Oropeza (UO) – First of all, I would you like to know what you thought of the meeting about Trotsky?

Yunier Mena (YM) – What I liked most about the academic meeting about Trotsky was the fact that I felt among communists, apart from the profound and just ideas I could hear.

UO.- I have noticed, since my previous visit to Havana, that now there is a different atmosphere, a lot of business, a lot of shopping, a very strong market environment, I imagine that, as you say: “feeling among communists”, is like breaking with something that has been growing in Havana.

YM.- In Havana and throughout the country, even in the Constitution of the Republic, there is an advance of capitalism, in my opinion. There is private property, money, and goods that do not come commonly through the channels of the State enter the country and this creates a mercantilist and unpleasant situation in the country.

UO.- As a young person, do you think that young people are inclined to capitalism, to pay more attention to consumption than to understanding what is happening?

YM.- There is everything, because reality is very complex, there are young people who don’t have a political thought, most of them into circus and bread. But there are young people who think about these issues, there are many who don’t say it, but surely very soon they will say it.

UO.- I’m asking you that because when the Soviet Union fell many young people were inclined towards capitalism. As you say, in the youth there is everything, but the great majority has been depoliticized. Besides, the vast majority of the youth, the only thing they knew about socialism was the iron grip of the bureaucracy. The old revolutionary traditions of Lenin’s and Trotsky’s time were forgotten and distorted. What do you think of this situation, that at a time when youth have to choose capitalism or a planned economy, where they would turn?

YM.- The youth and the majority of the people believe that capitalism is what is good, is natural, what works best and has taken man further. There is an imposition on people’s consciousness, on people’s criteria of a supposed success of capitalism, the economic success of capitalism. This is happening outside of Cuba and Cuba is no stranger to it.

UO: At a time when private property is advancing and the market is advancing, that false certainty of the people about the supposed success of capitalism is being reinforced.

The confidence that now exists in capitalism, what is the reason for this? I think there are two factors, on the one hand the control of the government bureaucracy, which eliminated workers’ democracy, direct participation in the decision-making of the working class, and on the other hand, the economic blockade that prevented industry from developing, and of course, the isolation of the revolution.

YM.- People’s support for capitalism has to do with several questions, on the one hand, capitalism itself, how it works, its human relations, its cultural and ideological dominance makes people think that it is the only thing they can have and aspire to. There is an ideological domain that makes people support capitalism. They think that society can only function that way. The apolitical nature of young people is due, on the one hand, to this natural reproduction of capitalism in the ideology of people who participate in economic activities and relations that have to do with capitalism.

Che said that man changes while reality changes, I agree with him, I think that the state that functions vertically cannot lead us to socialism, because man does not decide for himself, does not construct reality by himself and cannot transform himself. This apoliticism cannot be transformed until man is directly responsible for his future. Until the decisions that are taken are taken by the same ones that fall the results of that decision.

UO.- Finally, there is a very complex situation at the moment because the policy of American imperialism is being very aggressive in Venezuela, trying to hang the revolution that overthrows Maduro. It also has it with Cuba, even a few days ago the so-called Helms-Burton law has been retaken which proposes restricting the sending of money to Cuba to a maximum of $1,000 every three months, lawsuits by capitalist companies that were expropriated in the revolution, there is talk of a total blockade. There are complicated periods in sight for Cuba. What do you think the youth have to do, like you, who think that capitalism is not an alternative and at the same time opposes any imperialist intervention?

YM.- I think that we have to fight without fear against imperialism and against the bureaucracy that prevents socialism from advancing. What is needed is for people to build their own reality. We must consciously oppose capitalism, confront imperialism.

One of the things I sensed in the meeting about Trotsky’s ideas is that we are not alone. That there are people in different parts of the world who oppose capitalism. The support that Cuba and socialism has in Cuba was also shown. I think that it is important to defend Cuba and that we Cubans know that we are not alone, there are many people in the world who support us.

This socialism has many problems, but it can be improved and not go to capitalism. The possible socialism that we need is not the one that asks for capitalist participation, like private property or organized production over workers. We have to satisfy collective needs, we have to produce wealth organized by the workers themselves.

I think that this country needs to produce wealth, and this wealth is not produced by capitalism. We can produce wealth in a socialist way and distribute it better and discourage ourselves. Not to fall into the game of capitalism, capital is not interested in collective human development. Only democratic and productive socialism can promote solidarity and human development.

“Trotsky will walk in Cuba”

“Trotsky will walk in Cuba”

Interview with Frank García Hernádez

By La Izquierda Socialista

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

Interview with Frank García Hernández, Cuban intellectual, organizer of the First International Academic Event on Leon Trotsky, in Havana.

The Socialist Left (LIS): Would you like to tell me your impressions of the Trotsky meeting we just had?

Frank: I never imagined it was going to be so shocking. When it was over, just before the event ended, I noticed so many good intellectuals, including Robert Brenner, Paul LeBlanc, Gabriel García, Helmut Dahmer, Eric Toussaint, people who unfortunately don’t know each other in Cuba -except for comrade Eric- but who are excellent academics.

Almost 10 Trotskyist tendencies were present – who were not invited as such, all the exhibitors representing universities, institutions and academic journals came – and there was no clash between them. They sat at the same table, even though they have big political differences. And at the end, at the end of the last day, comrade Rob Lyons raised his left fist and began to sing The International. He could hardly continue, many did not know what to do, but later other voices joined in, and all of them: in Iranian, Indian, Turkish, Italian, German, French, Spanish, Portuguese the International was sung. And in a few minutes, we lived the World Revolution in that small hall. Then I realized something very important: Cuba, 60 years later, is still a revolutionary meeting point.

The event had a very great reception at a global level, a participation of academic institutions, of organizations like yours. The International Marxist Tendency was one of the first to reach out to us when the meeting was just an idea, a very big thank you to you who in record time published the book The Revolution Betrayed in order to bring it to Cuba: you will have the merit of being the ones to blame for reading it. We are also very grateful for the text by Alan Woods In Memory of Leon Trotsky, a basic text and therefore very useful for Cuban youth who still do not know it. In addition, the IEPC helped us a great deal by making it possible, thanks to comrades Pablo Oprinari and Sergio Moissen, to present the title of Trotsky Escritos Latinoamericanos. But it is very important to talk about the Leon Trotsky House Museum. So much so, that’s why I mention them last: so I can stop at them with more force. The compañera director: Gabriela Pérez Noriega, always wrote to us and asked us: “What can we help you with? To each one of the requests we made, she answered affirmatively. She never put a but, rather, she had such beautiful initiatives as bringing the first photographic exhibition on Trotsky that is exhibited in Cuba. And thanks to them, Santa Clara and Havana will be flooded with T-shirts with Trotsky’s image. Trotsky will walk in Cuba.

LIS: The meeting is very significant precisely because it is being held in Cuba, at a time when the revolution is being besieged by American imperialism: Trump’s speeches have been quite harsh in the last period asking Cuba to take its hands off Venezuela, if it doesn’t it is going to have very harsh repercussions for the island. Trump still thinks Latin America is his backyard. It is a fundamental task of a Marxist revolutionary to defend the conquests of the Cuban revolution from any imperialist attack. On the other hand there is a situation that strikes me, the situation inside Cuba has changed rapidly in recent years, particularly in Havana, there are hundreds maybe thousands of new businesses, it seems that a new class is forming, what do you think of this?

Frank: First I would like to say something, even if it has nothing to do with the event. The measures that Trump is taking against Cuba are not exactly a result of what is happening in Venezuela, but this president has had a term with terrible results. He has not put a brick in the wall he had promised on the border with Mexico, the economic war with China has not brought him economic dividends but only losses, his economy has not grown, he has fought with his best allies in the European Union. He knows that by trying to apply the Helms-Burton law he will win votes in the Cuban electorate in Florida, which weighs heavily in the presidential election.

Second, which has to do with the event, is the Cuban situation. We are learning to live with private property – class struggle through -. Some want us to live peacefully with private property and accept it as such. Even if we do, the class struggle runs through us.

The bourgeoisie is born with its media, its cultural policies, its consumerism. The prices of goods -due to the fact that they are quite deregulated in the capital- soar, since the bourgeoisie needs, in order to maintain its business, to consume more than what the working classes consume. The impact is even harder because the businesses that these class controls are essentially in the service sector. This leads to food hoarding and therefore: shortages. Something that does not happen in other regions of the country, like Santa Clara, because the bourgeoisie is more controlled by the government and there is less concentration of wealth.

But comrade Yunier Mena, a Cuban speaker at the event, a philology student, rightly affirms that, more than economic strength, the bourgeoisie has strength in its ideological impact. I explain why: they present themselves as successful Cubans, concerned about culture, animal rights, the LGTBIQ community; they appropriate a good part of civil society, they speak on its behalf, they present themselves with a renovating discourse, they say they are not interested in politics and that they are misunderstood by the Communist Party, they emphasize that they are Cubans and nothing else. The result: The society, mainly the Havana society, ends up admiring them.

On the other hand, the party doesn’t know what to do. It stimulated, propitiated and guaranteed the birth of this new – old – class. It does not fight them because they believe that the class struggle is to divide the people. They forget Fidel’s stance – which kept the bourgeoisie weak: he warned them again and again that they were the fruit of a provisional economic policy. Now, the new Constitution, while insisting on the construction of a communist society, gives constitutional guarantees to their form of property: private property, which is established and exists thanks to the exploitation of human beings by human beings.

I am sure that all this caught the attention of so many participants. Only as an audience did I receive the request of 192 people to attend the meeting; if all the exhibitors had attended, there would have been 51. If I had had a larger logistic structure, I would have gladly accepted it all.

What hurt me the most is that there was not much Cuban public because the event was not publicized, but what I like the most is that all Cubans who were at the event have taken with them a copy of The Revolution Betrayed.

LIS: Victor Hugo once said that when an idea has its moment, nothing can stop it. It seems to me that, as you say, although there was little diffusion of the event, Trotsky’s ideas and thought will have an impact on the next period here. We can’t say that this is the first time Trotsky has been known in Cuba, previously there were groups calling themselves Trotskyists that participated in the different revolutionary processes in Cuba, however, now the reappearance of this figure is given a very significant moment, capitalism is in a dead end, it offers nothing to youth, women and the working class. What can you say to the youth and workers about Trotsky’s figure and its impact on Cuba?

Frank: When ideas start, there’s no one to stop them, that’s very true. I want to limit something, it’s not surprising that Trotsky’s reception in Cuba is so good, what’s surprising is that Trotsky didn’t arrive sooner.

This return of Trotsky to Cuba can never be compared to his arrival in the year 32 when Juan Ramón Breá and Sandalio Junco brought him in a suitcase. We were talking, at the time, about a capitalist society in crisis, involved in a violent class struggle against a murderous dictatorship and with a people with a literacy level of less than 50%. That first Trotskyism gradually disappeared. After the decade of the 1950s, Cuban Trotskyism never surpassed 50 militants, almost always entrusting other organizations as tiny as them. When the Revolution triumphed, they were suffocated, not only by the persecution of the Popular Socialist Party, but also by the major events that were taking place. The working classes paid more attention to the attacks of imperialism and internal counterrevolution than to the controversies, complex for them, sometimes even extemporaneous, between Trotskyism and Stalinism.

At the same time, since the 1960s a critical, heterodox Marxism was fostered in Cuba, which was censored in the 1970s, but after the fall of the Soviet Union, it reappeared with tremendous force. That Marxism has stagnated a bit. It needs more theory. Where there is a great setback in the assimilation of Marxism today is in the university student body. They continue to identify it with the official discourse. That is why Trotsky, who is not present in the study programs, is so attractive to them. This already happened in the 90’s with Gramsci and it was tried to happen with Rosa Luxemburg but it did not bear fruit. 60 years of revolution, in spite of all the errors, completely transform the mentality of society. One of Fidel’s main achievements is that he was in charge of disengaging society by constantly offering culture as an emancipatory instrument. This approach to Trotsky starts from a Marxism already studied and assumed, something that will avoid any sectarian position.

In Santa Clara, a study circle composed of university students called Cuban Communist Forum has already arisen. They have a Facebook page and I call on the world militancy to show solidarity with them by sending them magazines and bibliographies of thinkers such as Daniel Bensaid, Pierre Broué, Isaac Deutscher, Ernest Mandel, Victor Serge, Alex Callinicos, Cornelius Castoriadis, Alan Woods, Tariq Ali, Michael Löwy… They urgently need theory. See if it is important to help these students, who as soon as they returned to Santa Clara began to spread the bibliography they brought and, as I already told you, especially The Revolution Betrayed, the short biography of Alan Woods and another text, also biographical, authored by Esme Choomara, in addition to some explanatory brochures of the Permanent Revolution provided by Paul Le Blanc. These young people are not organized as a political group, they are not interested in doing so. They are born as a circle of study and debate. They do not claim to be Trotskyists, but communists. They understand Trotsky as part of a system of ideas in which Marx, Engels, Lenin, Rosa Luxemburg, Mariategui, Gramsci, Che Guevara, Fidel.

Trotsky returns to Cuba, to the Cuban revolution 60 years later and the situation is completely different from when he came with Junco and Breá. The analyses being done now are neither extemporaneous nor supranational. Trotsky does not land in a quagmire. There was already a knowledge of him; in November 2016 a postgraduate course on his life and work had been given. This course led to the publication in a Santa Clara cultural magazine of a fragment of Trotsky’s speech when he founded the Red Army. What is needed now is literature. For this we have to work hard on the publication of the book that gathers the memories of the event. The book will end up being a before and after the meeting. It will be the first title published in Cuba that will be dedicated exclusively to Trotsky. I call for full solidarity with that dream and with the dream of holding a second international meeting in June 2020 in Sao Paulo: one of the most beautiful fruits of the Havana meeting.

LIS: Thank you very much, Frank, we thank you for everything you have done for the meeting and for the comrades of the International Marxist Tendency and the Leon Trotsky House Museum.

Frank: My greatest greetings and acknowledgments to the International Marxist Tendency, to comrade Alan Woods who sent an emotional message. The International Marxist Tendency were the first to reach out to us when this meeting was just an idea, they were the ones who established contact with the Leon Trotsky House Museum because we had no contact with them. They have been key to developing the event, a work of almost a year, they were tremendously understanding of all our problems, especially comrade Ricardo Márquez -alias el Che- who at any time I wrote to him on WhatsApp or Facebook and he, even at dawn, took the trouble to answer me, to help me coordinate with other people with whom I could not maintain communication due to technological problems. I know that behind him there is a whole team, a support structure, of colleagues like Ubaldo, the German colleague Rosa Carolina: the first foreigner who came to ask and see what was happening -then dozens came- colleague Jordi Martorell, who was always willing to come and who always had a strong bond with colleague Celia Hart -who was my very close friend. Thank you very much to all of you. Excellent magazine América Socialista, we hope to have more issues of this magazine in Cuba and be able to collaborate with it.

Frank Garcia Hernandez. Organizer of the first international academic event on Leon Trotsky, in Havana.

“Trotsky’s Work Being Known in Cuba”

Gabriel García Higueras: “What matters is Trotsky’s work being known in Cuba”

Gabriel García Higueras: “What matters is Trotsky’s work being known in Cuba”

In Havana, we interviewed Gabriel García Higueras, Peruvian researcher specializing in Trotsky’s work.

By La Izquierda Diario México

Tuesday May 14, 2019

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

García Higueras is also a university professor, author of Trotsky en el espejo de la historia (Essays), published in Mexico by Editorial Fontamara, and of Historia y perestroika. La revisión de la historia soviética en tiempos de Gorbachov (1987-1991). He is also the author of the Guide to the Museo Casa León Trotsky.

Daily Left (LID): How do you evaluate this event?

Gabriel García Higueras: This is an event of great academic and political importance. It is transcendental that an encounter of this nature has taken place in Cuba. As I said this afternoon, at the beginning of my presentation, since 1990 there has not been an international congress on Trotsky that brings together such a number of presentations and speakers from so many countries. Frank García’s call and organization have been magnificent, as well as the reception he has found in the public. The fact that it takes place in Cuba is unprecedented and will mark a milestone in the research on Trotsky that will be carried out in this country. It should also be noted that the conference is taking place despite not having sufficient organizational support. This is very meritorious and evidences the dedication and commitment of those who have made it a reality.

LID: What is the importance of this taking place in Cuba?

Gabriel García Higueras: Without a doubt, it is very important that this event has been allowed in Cuba, which also reveals a greater political openness to address issues that were previously censored. As is well known, for a long time Trotsky was a taboo figure on the island, since the revolutionary government of Cuba, by aligning itself with the bloc of communist countries, adopted the Stalinist version of his role in the Russian Revolution. Precisely, Leonardo Padura writes about this distorted vision in one of the texts that make up his recent book Agua por todas partes (Tusquets, 2019). So this event is a vindication of one of the essential figures of socialist thought in the twentieth century.

On the other hand, I think it is important that Trotsky’s work be made known to new generations of Cubans. In that sense, the presentation of two of his fundamental books: The Revolution Betrayed and Latin American Writings, will be of enormous importance in this event.

In addition, tomorrow we will have the scoop of world premiere of the documentary on the life of Trotsky in the process of editing, The Most Dangerous Man in the World, by filmmaker Lindy Laub, who has had the historical advice of Suzi Weissman. It is the most complete and best-documented film ever made about Trotsky. And I say this because I saw the trailer at the Leon Trotsky Museum in Mexico nine years ago.

LID: Why don’t you tell us what your participation consisted of?

Gabriel García Higueras: Well, I dealt with Trotsky’s historiographic representation in the Soviet Union during the perestroika. That subject is important because, at that time, a revision of the official history was initiated and, therefore, his figure as the protagonist of the Russian Revolution was recovered. Moreover, this revision allowed the appearance of new historical narratives about Trotsky, some of which are still circulating in Russia.

Due to the fifteen minutes I had for my presentation, I limited myself to presenting the main lines of the subject. I would also have liked to talk about the historical vision of Trotsky in Russia today.

LID: You also presented a book…

Gabriel García Higueras: Yes, this is Trotsky’s second edition in the mirror of history, published in Mexico two years ago. Although I couldn’t bring many copies from Lima, I’m excited that my book will be consulted in libraries by avid Cuban readers.

LID: What about Trotsky today?

Gabriel García Higueras: He is a thinker whose ideas are unavoidable to understand the main processes of the contemporary world. Trotsky reflected and wrote about such a diversity of problems that his ideas always illuminate our vision of reality. Just to cite one example, his theory is key to understanding the Russian Revolution and the historical process that began in 1917. In that perspective, his writings provide us with solid arguments to understand the degeneration of the first workers’ state and the causes for its disappearance.

Interviewed: Pablo Oprinari

You can also read: Trotsky revisited in Havana, Cuba

“In Cuba We Needed Trotsky”

THE LEFT DAILY MEXICO

May 19, 2019

“In Cuba we needed Trotsky to understand what happened in the Soviet Union.”

Pablo Oprinari interviewed Frank García Hernández, organizer of the recent “First International Academic Event on Leon Trotsky”, held in Cuba, in which the Leon Trotsky Center for Studies, Research and Publications (Argentina-Mexico) participated.

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

IdZ What is your assessment of the Trotsky event held in Cuba?

FG: I always thought that the event was going to mark a before and an after. I know that if we had done it in Brazil or Mexico -countries where it is possible that the 2nd and 3rd edition of this meeting will take place- it would not have been the same, because, although we have not had much financing due to all the economic problems that Cuba has, we did achieve a very large international participation, with high-level presenters such as Robert Brenner, Paul LeBlanc, Susy Weissman or Eric Toussaint, You have come [CEIP León Trotsky, N del E], those from the Karl Marx Center for Socialist Studies, the Casa León Trotsky Museum, researchers from the three most important universities in Brazil have arrived, participants and academics have come who at other times are not meeting because of the traditional disputes that their political organizations have, but who come because Cuba is everyone’s land and nobody’s.

Trotsky, Cuba and the current situation in the country have brought people from all over the world: from India, Iran, Turkey, Italy, Austria, Germany, France, Great Britain, Argentina, Canada, Spain, the United States, Mexico, Peru, Venezuela, Brazil, intellectuals from Colombia and Pakistan, who were finally unable to attend, Michael Lowy and Tariq Ali also wanted to be present and at least ten other exhibitors. The event, in fact, should have lasted four days, but it was impossible, almost impossible, and cannot leave. We had a very difficult logistical situation so we couldn’t receive a foreign audience. I hope you understood and didn’t bother with us. To those of us who asked them not to come, we never did so for political reasons, much less for personal reasons. If we had accepted the 192 applications for public participation we would have collapsed, in fact, you saw that in the room where we were, they would not have had space.

The only thing I didn’t like about the event is that there wasn’t much Cuban public, which I think was due to bad management, it’s our responsibility, and that could give the false idea that in Cuba there is no will to meet Trotsky. Moreover, the lack of time caused the program not to be ready for the first day.

But the event, for me, in spite of its problems, is a total advance. In addition, the Institute of Philosophy undertook to publish the memoirs of the event, an institute that if it had not been for him we would not be here today. We must also thank the director of Casa Benito Juárez, where this congress was held. And we would also like to thank the logistical support given to us by the Juan Marinello Cuban Institute of Cultural Research, which also seems to be preparing to collaborate in the publication of the memoirs.

If this is done, if this book is published, it would be the first time that a book dedicated to Trotsky and the sociopolitical-cultural phenomena that has been generated around him would appear in Cuba. Trotsky’s other text that appeared, as a book, was published in the sixties by the militants of the Revolutionary Workers’ Party (Trotskyist), who were militants in the Fourth International Posadista. That book did not travel around the country because it was confiscated and never went to press.

Were other articles or materials by Trotsky published?

FG: In Cuba, only the following articles by Trotsky have been published without suffering censorship: one in the Revolution newspaper, of the 26th of July movement, in the cultural supplement “Lunes de Revolución” where a very short excerpt from the History of the Russian Revolution, published by Guillermo Cabrera Infante, appeared. That was in 1960.

Later, in 2014-2015, “Lenin’s Last Struggle” was published in Cuba, a compilation of Lenin’s writings and letters, which was originally published by Pathfinder Publishing, which ceded its rights to the Social Sciences Publishing House; there appeared some letters from Trotsky to Lenin. And after I taught the postgraduate course on Leon Trotsky, in November 2016 – the first in Cuba and had a great impact on the student body – almost two years later, in January 2018, the centennial of the Red Army, part of Trotsky’s speech at the founding of the Red Army was published in a Santa Clara cultural magazine.

So now, when we publish this book, we are going to live in Cuba a before and an after, because when all the presentations that were made are published, we are going to skip the political taboo that is Trotsky. With Trotsky in Cuba something very similar happened to what the Peruvian writer Héctor Béjar says in his book, which was awarded the Casa de las Américas Essay Prize in 1966, when he stated that after the 20th Congress of the CPSU, we all knew about Stalin’s crimes but nobody told us that the one who was not a criminal was Trotsky.

And the same thing happened in Cuba: after the fall of the Soviet Union, we all knew about Stalin’s crimes, but no one here has said that Trotsky was not guilty of what he was accused of. That is the importance of the event. To begin to say in Cuba that nothing that was said about Trotsky is true. And Trotsky is not even mentioned in the history books that students receive. Maybe the university students know him, but it’s very difficult for high school students to know about him.

Without a doubt, Padura’s work, The Man Who Loved Dogs, helped arouse curiosity, but they have no book to go to cover the doubts and learn more. On the other hand, friend and comrade Celia María Hart Santamaría could not successfully spread Trotsky[‘s ideas] in Cuba. Circumstances made her end up being a sniper on the roof of a tower. No one saw her, no one could see her, even though they felt her shots, accurate, very accurate.

IdZ: They talk about the dynamics of the event and the first repercussions.

FG: The academic level is very good, excellent, there is no complaint. We have to thank everyone for their presence. There was even the collaboration of Lindy Laub, a well-known North American filmmaker, who had participated in the Festival del Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano, here in Havana in 1999, and Suzi Weissman, her producer, who in turn was a speaker. They both brought a documentary that we enjoyed the 42-minute work-in-progress, The Most Dangerous Man in the World with unpublished images that no one has ever seen. We did this in a small but very collaborative room of the Young Directors Exhibition. Unfortunately, there weren’t many Cubans, but the important thing is that it was projected in Cuba.

What is real is that Trotsky, as a historical character has had an impact on sectors of the Cuban university student body, since students from Santiago de Cuba wanted to come to the event, they came from Santa Clara without even having the economic conditions, they came from Matanzas. Today in Santa Clara and Havana there are students who are reading and studying the books that you and other comrades brought to the event. For them, for those Cuban students, I ask for the most solidary of the help. They have only two titles. So I call on internationalism to send them material, magazines, books.

Escritos Latinoamericanos is, moreover, a text that has impressed some Cuban historians very much, because we had never been able, or even knew, that León Bronstein had dedicated political analysis articles to the Cuban situation of his time and especially to the Bolshevik Leninist Party. For me, who wrote the history of Cuban Trotskyism, that is a fundamental contribution. Another important point is that this Friday Latin American Writings will be donated, along with the text by Gabriel García Higueras, Trotsky in the mirror of history, to the library of the House of the Americas, the institution that attracted intellectuals such as Cortázar, Benedetti, Galeano and that today continues to be one of the best points of convergence on the continent. This library is very much visited by the Havana intellectuals. Also this Friday, May 17, Writings… will arrive at the libraries of the Faculty of Philosophy and History, and at the Central Library of the University of Havana.

I always make a very necessary clarification: the event was an academic activity about Trotsky and all the political, social and cultural phenomena that came out of it. It was not a call for international Trotskyist convergence. The perception that we young people have that we feel part of the Cuban Marxist left, that we use Marxism to understand reality, is that Trotsky belongs to the system of communist ideas, to all the theory that Gramsci, Rosa Luxemburg, Lenin, Marx, Mariátegui give us. Some bureaucrats want to point out Trotskyists to us; I have nothing against Trotskyism, evidently, yes, some necessary and enriching divergences of criteria, but let’s remember that Stalin began to use that term to make believe that the followers of the Left Opposition were not Leninist Bolsheviks, but a tendency alien to the revolution.

We were missing Trotsky. We lacked Trotsky to understand what happened in the Soviet Union, because none of the referents of Marxism that I mentioned, as well as Che Guevara or Fidel Castro, could, for different reasons, give a systemic explanation of what happened. Trotsky has the courage to have done so since 1936, the courage to have developed a sociological analysis that we didn’t know about, and for which we Cubans are very interested.

Other Marxisms in Havana

MEDIUM

Other Marxisms in Havana: Trotsky revisited

By La Tizza: “…with the clenched left fist, “The International” was heard in several languages and in the voice of the participants, “.

By La Tizza

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

Photo La Tizza

The universalization of Marxism, beginning in the 19th century, is a reality that few people dare to contradict or ignore. The history – sometimes tragic, it is worth acknowledging – of how this universalization took place (the roads it has traveled, the bifurcations it has had and its contradictions and complexities) needs to be reconstructed as part of the cultural heritage of the Marxist tradition. Above all, this is because it has to be part of the struggle for the revolutionary transformation of the world. Following in the footsteps of one of the currents of Marxism, the one inaugurated by Lev Davidov Bronstein – better known as Trotsky – an academic meeting was held in Havana from May 6 to 8, [2019].

Under the decisive impulse of Frank García Hernández, of the Juan Marinello Cuban Institute of Cultural Research (ICICJM); and with the help of the Institute of Philosophy, the Casa Benito Juárez – headquarters of the debates -, in addition to the ICICJM itself, for Cuba; as well as the Casa Museo León Trostki, of the Federal District of Mexico, the event of study and tribute to the founder of the Red Army was held. More than forty foreign researchers met in Cuba – not a few of them militants in revolutionary organizations – who have dedicated part of their theoretical analyses and political itineraries to the personality and thought of the famous occupant of the Soviet armored train during the Civil War of 1918-1921. Together with their Cuban peers – who acted as moderators in the eight thematic roundtables that met during the three days – they outlined the political and theoretical ups and downs of the promoter of the Fourth International.

May 6 was devoted to characterizing the revolutionary trajectory and intellectual biography of Lev D. Trotski: his theoretical conceptions; his performance as a political leader and military strategist; his positions in the Soviet leadership before and after Lenin’s death; his exile and his assassination in Mexico. His ideas about the Permanent Revolution, uneven and combined development, the organization of the State and factory production in the conditions of socialist construction, among other topics, were revisited. At the end of the day, it became clear that Trotsky’s personality and thought have their own merits in the Marxist tradition, which need to be understood and explained as one of the referents of revolutionary movements in the contemporary world.

For their part, the dates of May 7 and 8 were conceived to understanding the transcendence of Trotskyist thought in two essential dimensions: in terms of political theory, aesthetics, art, literature… in the end of universal culture – and for this, three panels met in a very tight intermediate day – and in geographical terms, with their impact beyond Soviet borders, specifically in Turkey, Mexico, the United States, the Caribbean in general, Cuba in particular and South America – themes, with their specificities that occupied the hours of the last day and extended the sessions almost three hours beyond those originally planned – .

The days of the meeting were also a space for militant and committed solidarity – not without criticism – and internationalism with Cuba and Venezuela, immediate objectives of U.S. imperialist aggression. This was evidenced in multiple interventions that earned the most resounding applause in each of the thematic tables.

In all probability, the most important balance of the event was the set of questions that it left open – although more than one panelist tried to give him his own answer -; some of them could be summarized in:

– How can the socialist transition be managed in a conscious, organized and cultured way?

– How does the dynamic of the relations between (and the struggle of) social classes take place in the socialist transition, what role does the bureaucracy play in these dynamics?

– What strategies to follow in the face of capitalist reaction, especially its most stark expression, fascism in its various national and international manifestations?

Is the internationalization of struggles and proletarian internationalism a tactic, a strategy, a reason of state, a necessity of revolution, how to practice it?

– How are the noblest ideas about socialism and the revolutionary transformation of society perverted, what are the antidotes against bureaucratization and deformations, what lessons can be drawn from the experience of the USSR and all the socialism of the twentieth century?

– if socialism is not only a way of conceiving the expanded production and reproduction of the material and spiritual life of people and nations, how can we understand a different, not opposed, type of art, literature, everyday life… in short, a different type of culture – which, in Trotsky’s words, cannot be “proletarian”, but “socialist”?

– How to process and assume contradictions and differences in the revolutionary field when not all visions and practices are coincident? How to understand the difference, the antagonists and the enemies?

The previous ones are only a limited sample of the multiple questions that, with their concrete forms, Trotsky formulated in diverse moments. He gave it his own answers, but the strength that his questions still have gives an account of the need to retrace his steps and the whole Marxist tradition in all its complexities and contradictions, just as the revolutionary thought that was not buried with the rubble of the Berlin Wall advanced.

When around 7 p.m. on May 8, with the raised left clenched fist, the event dedicated to Lev D. Trotski ended and the universalization of Marxism opened a new chapter, this time from Havana.

Why Stalin Triumphed

Stalin’s Triumph

By way of an epilogue *

* This text and its notes are by Fernando Rojas, author of the compilation Leon Trotsky: Selected texts.

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Spanish original here:

In 1936, the USSR proclaimed its second constitution, the third of Soviet power if one takes into account the 1918 one when the Union did not exist. The Bolshevik Party and its by-then indisputable boss, Josef Stalin, had resolved – against the teachings of Marx and Engels – the way in which an isolated socialist state could create wealth and develop powerful productive forces.

The regime that was thus constitutionally consecrated was very homogeneous in its social composition due to the transformations undertaken “from above”, and its coercive methods – although not yet of a criminal nature. It had the most egalitarian levels of distribution of national income known in history.

It is useless to delve into the texts of Lenin in search of the keys to these results. As a matter of fact, both Stalin and his adversaries of the previous decade (the Twenties), appealed to the attitude of the late leader to justify their conflicting and even antagonistic positions.

The social and ideological basis of Stalin’s victory is found elsewhere, and it is not only attributable to the arbitrariness that prevailed in the State and the party ever since the process that began with the defeat of the Bukharinists around 1930. In fact, arbitrariness was “used” by all Bolshevik fractions to a greater or lesser degree – although it is true that, except for the Stalinists, all the others rejected it one after the other– and to the degrees in which it this is consubstantial with any revolution.

It is often and deliberately forgotten that the arbitrary actions of the Bolshevik Revolution, in its ascendant stage (1917– end of the twenties) (1) were fewer and much less serious than those of the bourgeois revolutions so glorified until recently. (Today, the masters of the world and their willing or unconscious satellites find it convenient to not glorify any revolution).

The key to Stalin’s triumph must be sought in the growing dreams of swift prosperity, peace and stability that inspire the masses to participate in any revolution.

Isaac Deutscher recognizes this condition in the first half of the Twenties, although he nuances his conclusion denouncing the manipulative intention of anti-Soviet historiography to counterpose that idyllic time to the bloody decade of the Thirties.

Leon Trotsky creatively applies the notion of the dialectical relationship between oppressed and oppressor to the relationship of the Soviet bureaucracy with the entire population in the Thirties.

One can coincide with both but, at the same time, the facts, the documents and the press – – even the Western media– confirm that the feeling of well-being and stability was present in important and broad sectors of Soviet society until the beginning of the war in 1941, though since the mid-1930s that feeling was contradictorily combined with fear.

It happened that arbitrariness gave way to crime. In the same year that the brand new Soviet constitution –the most advanced legislation known until then– was proclaimed,–the first “notorious” Moscow trials took place –notorious–for everyone except for those of us who were educated in the fidelity to the Soviet Union. These trials allowed Stalin to liquidate the cream of the leaders of the revolution and the Party.

Before being shot, the Bolshevik leaders were demoralized, forced to make confessions that concealed their pitiable condition of political losers to the country and the world and canceled their credibility as revolutionaries. In that perfidious manner, Stalin made sure that his adversaries could not claim the halos of martyrs. (2) Terror struck all dissidents and their families, and it became the norm.

Trotsky and Deutscher claim that Stalin did not feel safe, despite his absolute power. The dynamics of their explanation leads one to suppose that, successively, the Class replaced the People, the Party replaced the Class, the Fraction replaced the Party, and the Leader the Fraction, and – I infer from my readings–that this did not grant security, since there were always real or potential adversaries in the transit from one substitution to another. In my perception, such substitutions did not happen one after the other, but took place concomitantly and, many times following the logic of any revolution.

An essential question is that the Bolsheviks – Stalin first and foremost because he had been victorious in the struggle for power – had not solved the question of democracy. They knew that the bourgeois version of popular power – presented until today as “democratic” – was, and is, an absolute farce. However, they had not been able, despite their long debates on the matter and the just remonstrance of Rosa Luxemburg, to articulate an alternative which could be recognized and verified at the same time.

Lenin’s premonitions and warnings simply remained on paper. Had they been taken seriously – some of them were very concrete proposals – after 1924 the working class would have had a much more important role in the country and as a counterpart to the increasingly bureaucratic party than what it had at the triumph of the revolution. Incidentally, it did have it in the propaganda, but the facts proved otherwise.

However, until the defeat of Bukharin in 1930, the backdrop of far-reaching ideological discussions about the destiny of most of the planet’s population ignored intentionally or unconsciously until today, was not due to apathy –as Deutscher believes– but to a spontaneous massive participation in the conquest of a promising future for hundreds of millions of people, against the grain of the languishing soviets, since they had barely been designed to mobilize the protagonists of the taking of power in 1917.