Karl Marx 3

No One Can Ever Bury Marx

No One Can Ever Bury Marx

There is no Marxist who knows Marx’s work inside out and does not fight for social justice; if one rationally assumes his postulates, but does not vibrate in the face of injustice committed against other human beings, in any corner of the planet

by Enrique Ubieta Gómez

March 14, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

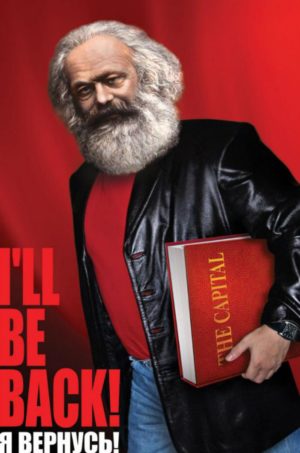

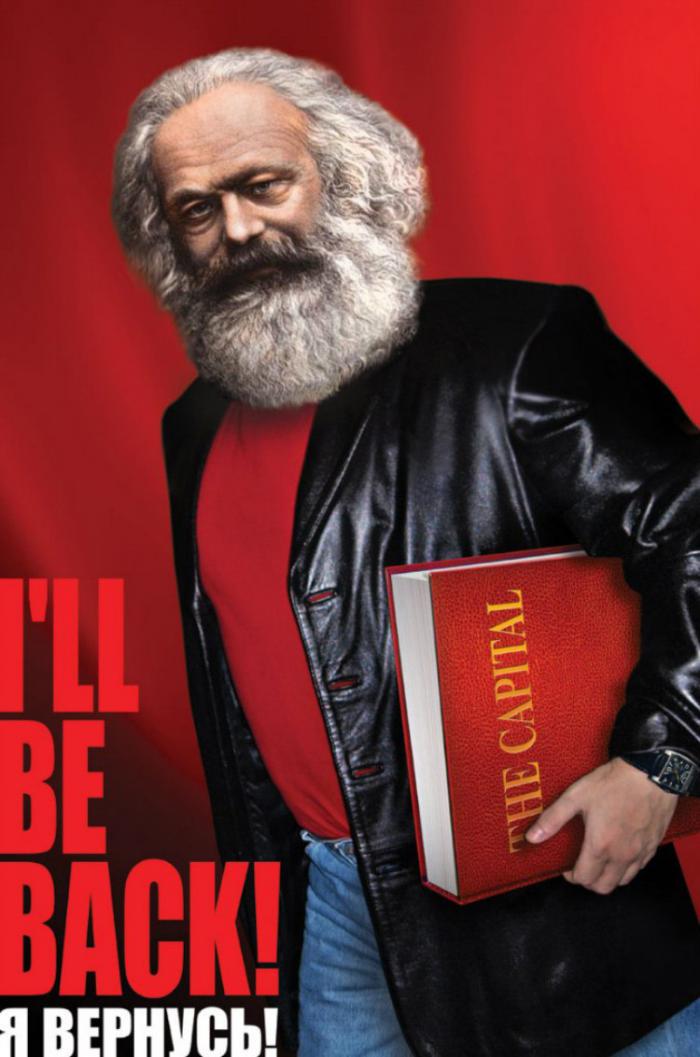

Illustration dedicated to Karl Marx Photo: Archive illustration

There is a drawing that imitates a photo, Karl Marx appears in a pitusa, a red pullover and leather jacket. Under his arm, he carries a volume of his masterpiece: Das Kapital. The Genius of Trier looks at us as he walks, impatient. The poster bears a legend, written in English and Russian: “I am back”. In another poster, Marx himself, now full-length, appears with a couple of university students; the professor and his students are almost dressed alike. This is recent propaganda by the Russian Communists. They’ve made one of Lenin’s as well. Sitting down, he holds a modern laptop on his knees and feverishly writes one of his revolutionary articles. The drawings connect, no doubt, with young people. They are doors that invite to be crossed.

On March 14, 137 years ago today, the greatest social thinker in history physically ceased to exist. His mark on modern culture is so profound that it is not necessary to know his work in depth to breathe its air. Humanity, whether it knows it or not, has assimilated many of his discoveries, just as, without having read or studied Copernicus or Darwin, it “knows” that the Earth is round and understands that evolution is a key factor in nature. The intellection of his work is, however, arduous: it demands dedication, study. Marx set out to understand capitalism, and he discovered its fundamental laws, in force despite its changes. He also discovered the path to overcome them. From a theoretical point of view, he was a man of action. But we are not given in simplifying capsules, nor in manuals.

His work demands active readers, creators. It demands native revolutions, capable of readjusting their paths, time and again, as Martí requested, in order to avoid the sieges and traps of Capital, its military, financial and media tentacles, and to conquer spaces of freedom, anti-colonial at first, and anti-neocolonial later. Fidel explained it as follows: “Marx’s theory was never a scheme: it was a conception, it was a method, it was an interpretation, it was a science. And science is applied to each concrete case. And no two concrete cases are exactly the same. The Cuban Revolution had the genius of Fidel, and a well-established tradition, whose roots go back to the independence and anti-imperialist thinking of José Martí and Antonio Maceo. It extends through a long list of combatants in the 20th century: Carlos Baliño, Julio Antonio Mella, Rubén Martínez Villena, Antonio Guiteras, Jesús Menéndez, Frank País, Ernesto Che Guevara…

There is no Marxist who knows Marx’s work inside out and does not fight for social justice. if one rationally assumes its postulates, but does not vibrate before injustice committed against other human beings, in any corner of the planet.

Ethics and science are basic assumptions. That is why in 2001 Fidel reaffirmed: “We will never renounce the principles we acquired in the struggle to bring all justice to our country by putting an end to the exploitation of man by man, inspired by the history of humanity and by the most preclarified theorists and promoters of a socialist system of production and distribution of wealth. It is the only one capable of creating a truly just and humane society: Marx, Engels and later Lenin. 137 years ago today, Karl Marx physically abandoned us. But no one will ever be able to bury him.

Marx Returns Again and Again

Marx Returns Again and Again

By Ariel Dacal Díaz

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

Friendship, family, love and politics cross in this film from side to side, which traps, sensitizes, moves thought, renews indignation, places the characters in their context and demands we take a stand on that very present past.

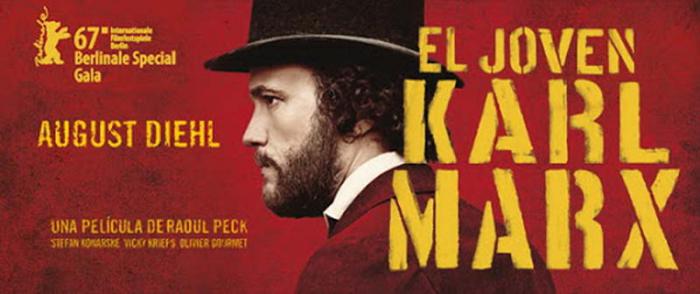

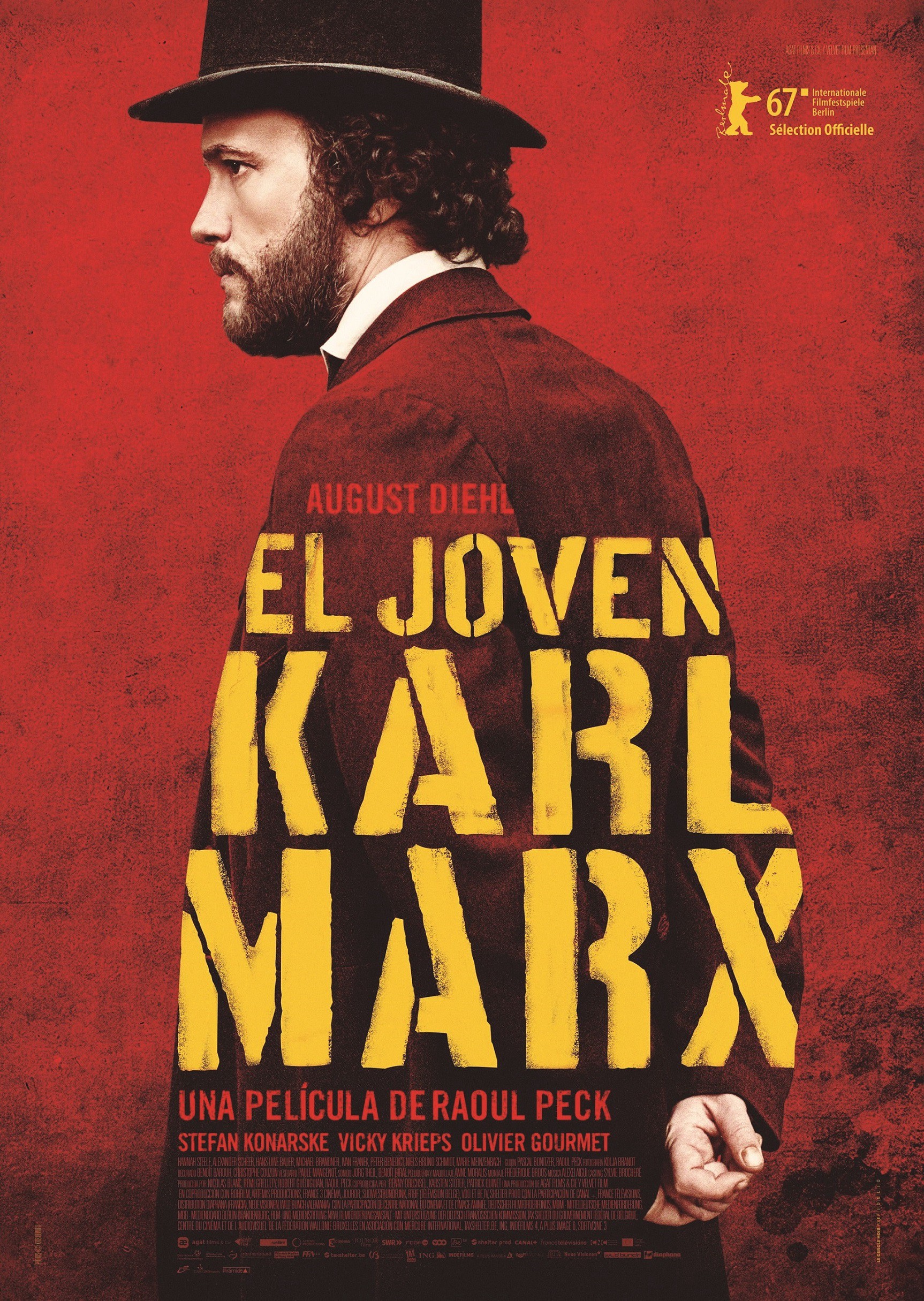

The film that motivates these lyrics, The Young Marx, is a daring and challenging work. It brings to our time an accessible and necessary Marx, both by his thought and his conduct.

This is material that takes up ideas with more than a century of statements, but which are not old at all: abolishing property as a natural right, unraveling the materialism of human conflicts, understanding work as the primary source of the creation of social wealth and assuming criticism as a revolutionary method of emancipation.

The film offers revolutionary and loving content at the same time. It tells us about the life of a young man who, without looking for future transcendence, lived his constant conflicts with passion. A man aware of the paradox of his existence: having written so much about money having so little money. The young man who confesses to his close friend: “I need to write, but I also need to feed my family. He who, along with the material deprivation, suffered persecution and confronted the authorities in every country he stepped on. As Eduardo Galeano recalls, “this prophet of the transformation of the world spent his life fleeing from the police and the creditors”.

The story of the young Marx is also one of paradigmatic friendship with the young Engels, who became an irreplaceable complement to his theoretical and political creation, in support of his existential contradictions and indispensable economic support of the family in the face of the difficulties the German philosopher had in finding stable paid work.

Jenny of Westphalia, his wife, was a vital force in the life of the Moor (as he was known); another fair and wise recreation by the film. She was a critical, enlightened, scathing woman, consistent with ideals that led her to renounce her aristocratic privileges; who was, at the same time, a loving spouse, a supporter in daily material life and a companion of great intellectual depth.

The young philosopher, recreated in almost two hours of fiction, took up the struggle against the horrors of nascent capitalism with vehemence and certainty. He understood, demonstrated and criticized the exploitative essence of this socio-economic system, and chose to be on the side of the workers in this struggle. He testified to the coherence between the ideas put forward and the practice of life: he interpreted the world and dedicated himself to transforming it. He went further and proposed an alternative: communist society.

This man committed too many transgressions throughout his life to be forgiven by the usurers of history and their emissaries. It is an impertinent ghost that awakens the wrath of the powerful of the earth; those who in the face of the fear of losing their privileges are capable, to avoid it, of the most atrocious episodes. Marx, the spoilsport of the conformists, the crowd agitator, the one who harasses the power of the powerless, is a danger with which they have not been able to deal.

The bundle of lies, half-truths and distortions poured out on his life; the refined, scientific and enlightened criticism that flatly denies him; the attempt to reduce his ideas to a condition of utopia without a future and the foisted faults that do not touch him, fade before his transparent, verifiable, radical, sharp and undeniable truth.

It is not by chance or whim that Marx returns again and again. A world of established injustices still persists and must be interpreted, criticized and transformed.

It is no accident that I come back young and ask you in a radical way, “What is your political position in life? If you haven’t asked yourself this question yet, then I recommend this film.

The Young Karl Marx

The Young Karl Marx

The young Karl Marx can be seen next month on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the birth of the author of Das Kapital

—————————————————–

Author: Rolando Pérez Betancourt | internet@granma.cu

April 22, 2018 20:04:56

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

The young Karl Marx can be seen next month on the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the birth of the author of Das Kapital

Next May 5, 200 years after the birth of Karl Marx, this proven director, who is undoubtedly the Haitian Raoul Peck, made the German film The Young Karl Marx in 2017, a film to which even those who do not sympathize with Marxism have had to grant him artistic merit and the rigor of the concepts on which it is based.

The film tells of two young people who did not know firsthand the ruthless exploitation of capitalism in their day – and of course the other is Frederick Engels – and yet set in motion a movement that overflowed the antagonistic politics of their time and has inspired the emancipatory yearnings of millions of people around the world over the course of a century and a half.

Biographical notes on some lives and events that began in 1843 and ended in 1848 with the edition of the Communist Manifesto, years in which Marx and Engels met and solidified an eternal friendship. The director Raoul Peck, adapting himself to the didactic demands of the biopic, shows that even in a genre, the biography, coming from a consolidated literary tradition at the service of bourgeois glorification, back in the 19th century, can innovate and make more attractive a narrative whose vital substance is the weight of ideas. A well-told film with a convincing August Diehl as the young Marx, it is a story not to be missed by those who want to know how a key text of contemporary political thought was forged, which is like saying how the Communist Manifesto was forged.

Haitian Raoul Peck was forced to emigrate with his family to the Congo after the Duvalier dictatorship threatened them with death. He was closely linked to African reality and studied filmmaking in Berlin. His films, such as Lumumba and I’m Not Your Negro, the latter a documentary about racism in the United States that was nominated for last year’s Oscar, highlights the political and social concerns of this filmmaker. Director Peck – and the film makes this very clear – is not interested in wax figures. Hence we will see a passionate young Marx, a troublemaker, a drunkard at times, a Marx with defects, as his wife reproaches him, at times self-sufficient, a person of flesh and blood. Peck’s Marx is also overflowing with a youthful energy channeled under the imperative that happiness, the meaning of life, becomes concrete for him in an act of resistance and constant struggle against social injustice.

A film for any kind of audience, but one that scholars of history and Marxism will enjoy very much as they witness the dialectical battles established between the two young revolutionaries and other figures who understood only part of what the struggle for a new world should be. Thus we will see a gallery of these characters in this story that, faithful to reality, dedicates a special treatment to the women who influenced the life of Marx and Engels, and not only in the love aspect, but also contributing ideas.

Excellent moments are recreated, such as when the young people are introduced and the director conceives the scene as a train wreck, with an ironic Marx reproaching his great friend for the golden buttons he wore on his jacket the day they first met. From the beginning, both face their egos, then show mutual admiration, and finally end up in a night party. From then on they will fight together against censorship and police raids, riots and riots that will augur the strengthening of the workers’ movement, which until then had been disorganized in no small measure.

Although the film takes fictional licenses as is usual in any biography, historically it is impeccable. At the same tim, nourishing new points of view concerning this present of ours, contaminated by many of the contradictions then predominant and perfectly explained in Das Kapital, the film is a masterpiece for then and now. It’s not for pleasure that director Raoul Peck concludes his film with a dynamic editing that alludes to the perennial validity of Marxism. First, we’ll see the historic photo of Mary and Frederick, Jenny and Karl Marx and No Direction Home, played by Bob Dylan, a collage of photos and images that remind us of what the world has been like over the last 60 or 70 years. It’s a way of telling us that the two young friends are still as relevant as when they wrote 170 years ago that a specter was haunting the world.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

You must be logged in to post a comment.