Somos Jovenes 6

Simone de Beauvoir

Simone de Beauvoir

Simone de Beauvoir

A tireless fighter for women’s rights

Symbol of the and militant protesting woman of the feminist movement, the French novelist visited Cuba and, hand in hand with its main leaders, learned about the Revolution and the role of the so-called weaker sex in the emerging Caribbean social process.

By Javier Gómez Lastra

May 26, 2016

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

“The fact that determines the present status of women is the stubborn survival of the oldest traditions in the new civilization being outlined. That is what is unknown to hasty observers who see women as inferior to the opportunities offered to them today, or who see only dangerous temptations in those opportunities. The truth is that her situation lacks balance, and for that reason it is very difficult for her to adapt to it. (…)

“The fact that determines the present status of women is the stubborn survival of the oldest traditions in the new civilization being outlined. That is what is unknown to hasty observers who see women as inferior to the opportunities offered to them today, or who see only dangerous temptations in those opportunities. The truth is that her situation lacks balance, and for that reason it is very difficult for her to adapt to it. (…)

“Everything still encourages the unmarried young woman to expect ‘Prince Charming’ fortune and happiness rather than to attempt the difficult and uncertain conquest alone. In particular, it will give her the hope of reaching a higher social stratum than her own, a miracle that will not reward her life’s work. But such hope is dire, because it divides their energies and interests; it is a division that is perhaps the most serious disadvantage for women. The parents still educate the daughter with a view to marriage more than they promote her personal development, and the daughter sees in it so many advantages (…)”.

This text, taken from the work “Le Deuxième Sexe” or “The Second Sex” by Simone de Beauvoir, a French writer, narrator and philosopher and an essential figure in 20th-Century literature and thought, was a theoretical starting point for various feminist groups and became a classic work of contemporary ideology.

The piece, which breaks the existing canons in Europe since the Second World War, tells a story related to the social status of women and analyzes the different characteristics of male oppression.

It also exposes the gender situation from the point of view of biology, psychoanalysis and Marxism, and destroys the existing feminine myths, inciting the search for the authentic and full gender liberation.

Considered ambitious, the text also maintains that the struggle for women’s emancipation is different and parallel to that of the classes and that the main problem to be faced by the so-called weaker sex is not the ideological but the economic front.

The publication evoked strong reactions because of the marked character of nonconformity that the women of that time began to show.

The big push for gender equality

The beginning of the second half of the 20th century had very particular characteristics in the socio-cultural field in Europe. If anything brought about radical changes in ethical, political and philosophical thought in the countries of the Old Continent after the World Wars, it was the enormous need to achieve fundamental human rights and the emancipation of women.

Faced with the example of the policy of equality for all, applied by the governments of the nations of the newly created socialist bloc, many thinkers, human rights fighters, writers, poets, philosophers, and even politicians in Western Europe took a 180-degree turn in their way of valuing life and began to call for true equality between men and between men and women.

It was in this context that Simone de Beauvoir stood out and left a deep mark on the universal history of the world, leaving behind not only her extensive literary work, but also her tireless struggle.

In spite of her bourgeois origin, from a very young age the intellectual knew the difficulties of her contemporaries in a world dominated by men, markedly masculine, made in the image and likeness of the male and where women were relegated to domestic chores or simply to love.

Her work reflected women’s problems, marked by exclusion from production and home-based processes and purely reproductive functions, which represented the loss of all social ties and the possibility of being free.

A radical change

Simone was born in Paris on January 9th, 1908, in a district where coffee shops were beginning to proliferate, where literary gatherings were present and intellectual environments that logically influenced the writer’s education were created.

Very early on she excelled as a brilliant student and studied philosophy at the Sorbonne. Until 1943, she was involved in teaching in high schools in Marseille, Rouen and Paris.

At the age of eighteen, she wrote the first literary essay where the protagonist has many traits in common with her. From that moment on, literature played an essential role in her work.

In 1929 he met the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, who became her companion for the rest of her life. Together they shared almost five decades of existence.

Sartre’s influence was unquestionable and Simone began to make use of her existential freedom. This led her to renounce her family and friends, adapting to the real world and choosing a new system of life based on her encounter with the philosopher.

Under these principles, she managed to penetrate the world of the Parisian intellectuals of the 1930s, being one of the few women that this closed universe came to accept.

Extensive literary legacy

Extensive literary legacy

According to the vast majority of critics, researchers and scholars of Simone’s literature, in her literary texts she dared to revise the concepts of history and character and incorporated, from an existentialist perspective, the themes of freedom, situation and commitment.

Together with Sartre, Albert Camus and Merleau-Ponty, among others, she founded the magazine Les Temps Modernes [Modern Times], whose first issue was published in October 1945 and became a political and cultural reference point for French thought in the mid-20th century.

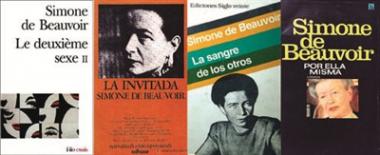

The thinker’s extensive work includes the texts “The Guest” (1943), “The Blood of Others” (1944), “Pyrrhus and Cinema” (1944), “All Men are Mortal” (1946), “For a Morality of Ambiguity” (1947), “America Today” (1948) and “The Farewell Ceremony” (1981).

In the latter, she openly dealt with the curious love relationship, from her youthful days to her old age, and the death of her companion, which implies their hard separation. Despite the absolute identification between them, they never shared the same roof, making use of freedom and with no other purpose than the mutual need to find each other, which allowed them to achieve a perfect symbiosis.

The work ends with the striking phrase: “His death separates us. My death will not bring us together, it is so. It’s been a long time since our lives could have melted together.

In the mid-twentieth century, with some feminists, she also established the Women’s Rights League, which set out to react firmly to any sexist discrimination, and prepared a special issue of Modern Times to discuss the subject.

Her many testimonial and autobiographical titles also included other texts such as “Memoirs of a Formal Young Woman” (1958), “The Fullness of Life” (1960), “The Power of Things” (1963), “A Very Sweet death” (1964), “Old age” (1968), “The End of Accounts” (1972) and “The Farewell Ceremony” (1981).

Character is destiny

The Algerian war broke out in 1954 and Simone felt powerless in the face of reality, thus beginning her period of political struggle.

She took part in anti-fascist demonstrations and gave lectures to the students, but all attempts to impose criteria against the system were unsuccessful, and, despite her efforts, Charles de Gaulle was declared President of the Republic.

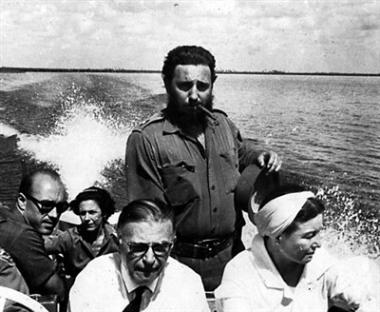

This new political situation prompted Simone to rekindle the need to rebel once again, and she agreed to accompany Sartre to Cuba in 1960. There she met Fidel Castro and Ernesto Che Guevara, among other revolutionaries, in Havana. Cuban photographer Alberto Korda documented the meeting between the couple and the two leaders.

Both Sartre and Simone were always fascinated by the Heroic Guerrilla. At the time of his death, seven years later, Sartre wrote: “Che was not only an intellectual, but also the most complete human being of our time”.

The couple spent almost two months working on the main island of the Antilles, which led to their subsequent and continued dedication to the defense of the Cuban Revolution.

They made an intense tour of the island, which included a tour of the Ciénaga Zapata swamp, the inspirational examination of the book “Sartre Visits Cuba”, published in Havana in 1960 by Ediciones Revolución. In its pages, the philosopher narrated his experiences in the country.

Fundamental decade for women and their rights

The Frenchwoman’s ideas soon reached the rest of the world and Simone de Beauvoir centers began to proliferate everywhere.

The emancipation of women was her ideal of struggle. Without denying the biological differences, she was able to denounce a whole system of oppression that worked – and still persists – from levels such as the home and that can extend to entire nations where one sex is established and dominated by another.

Her main ideology was based on equal opportunities for both men and women and on the true emancipation of all, both at work and in society.

Simone disappeared physically in 1986, but her intense work of ideological activism and broad literary exercise remain imperishable as a sure guide to the struggle for full equality. This is what her work testifies to.

Marx Returns Again and Again

Marx Returns Again and Again

By Ariel Dacal Díaz

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

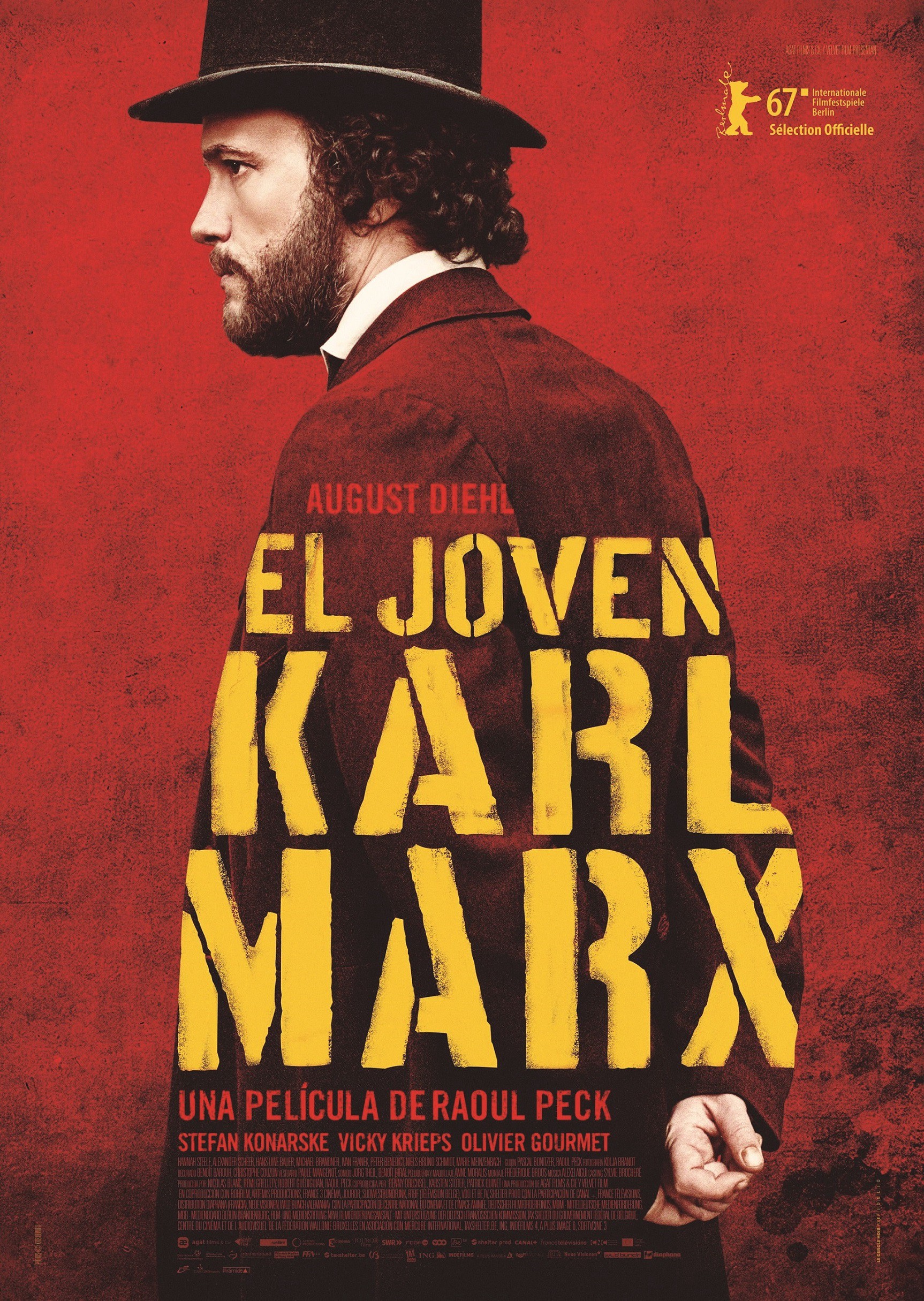

Friendship, family, love and politics cross in this film from side to side, which traps, sensitizes, moves thought, renews indignation, places the characters in their context and demands we take a stand on that very present past.

The film that motivates these lyrics, The Young Marx, is a daring and challenging work. It brings to our time an accessible and necessary Marx, both by his thought and his conduct.

This is material that takes up ideas with more than a century of statements, but which are not old at all: abolishing property as a natural right, unraveling the materialism of human conflicts, understanding work as the primary source of the creation of social wealth and assuming criticism as a revolutionary method of emancipation.

The film offers revolutionary and loving content at the same time. It tells us about the life of a young man who, without looking for future transcendence, lived his constant conflicts with passion. A man aware of the paradox of his existence: having written so much about money having so little money. The young man who confesses to his close friend: “I need to write, but I also need to feed my family. He who, along with the material deprivation, suffered persecution and confronted the authorities in every country he stepped on. As Eduardo Galeano recalls, “this prophet of the transformation of the world spent his life fleeing from the police and the creditors”.

The story of the young Marx is also one of paradigmatic friendship with the young Engels, who became an irreplaceable complement to his theoretical and political creation, in support of his existential contradictions and indispensable economic support of the family in the face of the difficulties the German philosopher had in finding stable paid work.

Jenny of Westphalia, his wife, was a vital force in the life of the Moor (as he was known); another fair and wise recreation by the film. She was a critical, enlightened, scathing woman, consistent with ideals that led her to renounce her aristocratic privileges; who was, at the same time, a loving spouse, a supporter in daily material life and a companion of great intellectual depth.

The young philosopher, recreated in almost two hours of fiction, took up the struggle against the horrors of nascent capitalism with vehemence and certainty. He understood, demonstrated and criticized the exploitative essence of this socio-economic system, and chose to be on the side of the workers in this struggle. He testified to the coherence between the ideas put forward and the practice of life: he interpreted the world and dedicated himself to transforming it. He went further and proposed an alternative: communist society.

This man committed too many transgressions throughout his life to be forgiven by the usurers of history and their emissaries. It is an impertinent ghost that awakens the wrath of the powerful of the earth; those who in the face of the fear of losing their privileges are capable, to avoid it, of the most atrocious episodes. Marx, the spoilsport of the conformists, the crowd agitator, the one who harasses the power of the powerless, is a danger with which they have not been able to deal.

The bundle of lies, half-truths and distortions poured out on his life; the refined, scientific and enlightened criticism that flatly denies him; the attempt to reduce his ideas to a condition of utopia without a future and the foisted faults that do not touch him, fade before his transparent, verifiable, radical, sharp and undeniable truth.

It is not by chance or whim that Marx returns again and again. A world of established injustices still persists and must be interpreted, criticized and transformed.

It is no accident that I come back young and ask you in a radical way, “What is your political position in life? If you haven’t asked yourself this question yet, then I recommend this film.

Six Minutes and Twenty Seconds

SOMOS JOVENES

Six Minutes and Twenty Seconds

By Gisselle Morales

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

She may not be communist, as the National Rifle Association has begun to call her. It is most likely that he is not a communist, to be clear, but neither does she have to be a communist for me to admire the determination with which she has stood up for arms control. Her name is Emma González and she is a descendant of Cubans.

She wasn’t supposed to go through what happened, crouched in what a madman did in high school with a combat weapon. Nor should she have become the leader of a movement that demands the right to life over the right – “blessed be the Second Amendment” – to own and bear arms. Politicians over the age of eighteen should be responsible for ensuring the safety of citizens.

“If the president comes to tell me in my face that he regrets this tragedy, which should not have happened, I would ask him how much money he receives from the National Rifle Association,” she had cried out to the crowd outside the Fort Lauderdale Federal Court, just days after the massacre, to ask the government for regulations to stop the lucrative arms trade.

But Trump, who often has the delicacy of a hippopotamus, didn’t think it would be a good idea to ban the sale of automatic rifles to citizens with psychiatric histories. The first thing that came to his mind – and he shot off his mouth without thinking too much – was the proposal to distribute weapons to teachers and students, bulletproof vests. After that, turn it off and let’s go.

Luckily, Emma Gonzalez and the rest of Parkland’s survivors have it made it clear: they had warned about Nikolas Cruz’s mental problems and are sure that the nineteen-year-old boy would not have done so much damage with a knife.

It is true that spooky assaults do exist, because some people cut themselves and even kill themselves with machetes and knives at popular festivities or in any corner fights, but there is no comparison between the magnitude of both types of killings.

That is why, on Saturday, March 24, 2018, while young people, adults, the elderly and children were demonstrating in the main American cities, and in cities around the world the, rise of the pacifist movement gave it a universal character. Emma González, wearing an olive green jacket with a Cuban flag sewn on her right shoulder, stood in front of the microphone in Washington and was silent; a silence of almost six minutes and twenty seconds, just the time it took the shooter to kill seventeen students and traumatize a school, a city, a state, a country forever.

Emma González, a descendant of Cubans, knows it like no one else: there are silences which speak volumes.

Originally published in the blog Cubaprofunda.

One For All

One For All

One For All

By Eldys Baratute

January 16, 2018

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

Dayana the thinker knows that other Dayanas live next to her: the smiling Dayana, the annoying Dayana, the cowardly Dayana and the Dayana who takes the blue pills. Although they live together, they are very different from each other.

Dayana the thinker is in charge of analyzing and criticizing everything that the others have done. The smiling Dayana spends the day cheerful, as if someone were tickling her. The annoying Dayana breaks plates on the floor, shouts, hits and curses. The cowardly Dayana is afraid of everything and prefers to spend her time huddled in a corner, afraid of being hurt. And the Dayana who takes the blue pills is in a rut all the time, looking at a lost spot on the horizon, as if she were looking for something but she doesn’t know yet what it is.

All Dayanas are happy, in their own way, all but the Dayana who takes the blue pills. Dayana the thinker enjoys criticizing what the others do. The laughing woman doesn’t need any reason to laugh, she knows she’s happy, even if she doesn’t know why. The annoying Dayana finds happiness when she hears the plates breaking on the floor, when she feels the crash of her swear words against the wall or her fists against the door. The cowardly Dayana is happy because she has a space in which to snuggle, even if it is small, dark, and uncomfortable, but her own. But the one who takes blue pills can’t find happiness anywhere, she doesn’t even bother to look for it.

Every Dayana dreams, except the Dayana who takes the blue pills. The thinker dreams that she will be an important philosopher, that she will go around the world giving conferences, just as important and that many thinkers follow her and ask her for autograph. The smiling Dayana dreams that one day she finally discovers the reason for her laughter, and that makes her laugh even more. Sometimes, while she sleeps, the others hear loud laughter, which stirs up the house. La Dayana annoys dreams that sometime, when she manages to spend 7 days and 645 hours, 43 minutes and 6 seconds screaming in front of the sea, all her annoyance will disappear and she would be a normal Dayana, without breaking the plates, shouting, hitting or cursing. The coward dreams that she is an amazon, or a knight in armor, or a cowgirl, or an armed policewoman, who goes out to defend others.

But the one who takes the blue pills hardly ever dreams, and when she does, all she sees is a white ceiling on top of white walls. That’s why, because she has no dreams, she never closes her eyes and prefers to look at a faraway spot while swinging on an armchair. That really worries the others. They know that the fault lies with those blue pills that force her to look for something on the horizon, something she herself doesn’t even know what it is. So they decided to throw away the tablets once and for all. Only then would that Dayana find happiness.

Dayana the thinker kept thinking about all the possible solutions to eliminate them from the face of the earth. The smiling Dayana went to find the scientist who invented them to ask him, on her knees if necessary, not to make them again. They weren’t doing anybody any good anyway. The annoying Dayana went out to look for a crane that would demolish every pill factory in its path. The cowardly Dayana wanted to buy all the medicines in the world, but when she stood in front of the pharmacy counter she was afraid that the salesgirl would ask for prescriptions, methods and cards and ran away.

They all came back empty-handed. Dayana the thinker had run out of new ideas. The laughing girl couldn’t find the scientist who invented the pills. The annoying woman couldn’t get fuel for her crane and the coward…

Then they all came up with a brilliant, brilliant idea, an idea that can only be possible when several days come together. They worked together all night, side by side, as if instead of four they were one. The next day, when the Dayana taking the pills got out of bed, she noticed that instead of blue the pills were white, red, purple, black and pink. She ran through every corner of the house in desperation. In the library she found Dayana the thinker philosophizing about the existence of man. In the courtyard she found the smiling Dayana, happy because a sunflower had bloomed. In the kitchen, she found the annoying Dayana braking plates. In her dark corner she found the coward, huddled as usual. Everything was normal. The only thing he didn’t find were the blue pills she thought she couldn’t live without.

For the first time in a long time the Dayana of the Blue Pills went the whole day without taking any. At first she was smiling, then upset, then she was scared to the minute and then she thought about everything she had done since dawn. It was one and several days at a time.

But that night, whens he huddled in her bed, she began to see for the first time the white walls of her dream, of all colors.

An Ode to the Lenin School

An Ode to the Lenin School

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

By Dario Alejandro Escobar

The nostalgic adult would like to go back over his memories and relive his times of glory and pleasure. The Lenin has on its students and teachers that magical effect that falls in love and compromises, perhaps ridiculous for the uninitiated in this youth brotherhood.

It doesn’t matter if they graduated, if they stayed a year or a month: the time argument is irrelevant. Because if you had the opportunity to live there, even if it was just a short period of time, you will be fascinated by the wonderful woman who deflowers you to become a different human being, almost always better.

The Vocational Institute of Exact Sciences Vladimir Ilich Lenin is forty-four years old today. It is easy to write and quicker to say, but it would be unfair to think of the thousands of students who have passed through their classrooms and hostels as mere data for a report.

The Lenin must be evoked in the new sensations of the first day as we walk, aisle after aisle, through its accomplice buildings. In the furtive and deep loves, those that shake our chest and make our face blush if we remember them. In the tears of many in the face of powerlessness for not understanding enough a subject that diminished – let’s be honest and admit it now – academic qualification and also personal pride. In the “infamous” guards on weekends; in the passes “removed” by the accumulation of reports; in the chaotic recreations, as close as possible to the meaning of “party”, even after the ones experienced in my special college years.

In those recreational spaces of the Lenin I learned to dance casino and to chant Silvio Rodríguez with any deflecting guitar. In the Lenin I smoked for the first time and in its nights I wrote my first attempts at literature.

The School has invariably shown some elitist inspiration. There’s no point in denying it. From the ways to get in, to the social and academic division of its groups, everything pointed towards excellence and exclusivity; but it has also had an avant-garde vocation. It wanted – and in my opinion it has succeeded in general – in training the most integral pre-university students. The one who knows the natural and exact sciences in above-average detail, and in turn has read a good number of the classics of literature or traditional and contemporary music. At least it was like that back in the day when I studied there

For being the avant-garde school that sheltered us, we venerated it. For developing the potential skills of your students, for making us grow from study, work and responsibility towards ourselves.

It is in the human and intellectual quality of its best students that the magic of the Lenin School resides. More than a decade after being abandoned by my fellow students, Vocations continues to graduate restless boys: boys who arrive at university with a desire to “eat the world”.

So much time later, and with a very important part of its graduates residing outside the country, parties are celebrated where people with antipodean differences in many aspects of life meet: ideological, sexual, and geographic, but united by the circular monogram very red with an atom in the center, worn in the sleeve of the shirt, or of the blouse, during the preuniversity.

I still find myself in the streets, in guaguas [buses], and more and more frequently on the Internet, people of my year, whom I greet with nothing else in common but to recognize us from that place. The school has remained engraved in the collective memory of its students as a great sect of friendship, a religion that few have renounced. A beautiful manifestation of memory grateful to the past.

These days I can’t get in to tour the school the way I want to. Bureaucratic reasons are holding me back. The Lenin is falling apart and there are those who justify laziness with incredible arguments. It hurts a lot but it doesn’t matter, because I have so much accumulated memory, so many friends scattered around, so many songs evocative of innocence, that no barrier can prevent me from feeling like the first time, a Lenin School student again and again when it comes to Graduation Day.

Against Harassment

Against Harassment

Against Harassment

By Mónica Baró Sánchez*

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

No, you can’t exercise in peace on the Fifth Avenue promenade or in similar spaces without at least five men, if you’re lucky, bothering you, saying sloppy things and looking at you like a bloodhound with their tongues out. With the faces of morons.

If you stretch out because your leg and if you do sit-ups because your buttocks. They remember young boys leaving priest’s school after months of not seeing a woman.

Sometimes I feel like taking off a tennis shoe and hitting them on the head to see if I can kill them with some obsolete neurons until they start to behave like the men they should be. Or to go out one afternoon and start messing with them in the same way so that they feel how unbearable they are. Let’s see if they stop seeing and treating women as something to have sex with and discover that we are people, that we feel, that we think and, above all, that we have dignity.

I don’t want to be looked at like that anymore. That doesn’t raise my self-esteem. Being looked at as one thing humiliates me, assaults me. I don’t exercise for men, I don’t wear a short dress for men, I don’t paint my lips for men, I don’t dance and I don’t shake my butt for men, I don’t smile for men.

I do everything for myself and for myself. And I’m pretty hard to please. When I’m alone I keep doing all that. Because I like to like myself and when I stop liking myself I try to like myself again. Me to me. Not to anyone. I like that I like my body when I dance, my lips when I paint them, my hair when I let go, my thighs and my belly when I dress myself short and even my ligaments when I stretch.

Women deserve to be treated like women, not like orifices. No matter what we do or how we dress. I’m sure there’s not a single man who finishes his workout and needs to publish something like this. Peace for me today is that if a man is going to look at me he must look me in the eye. And be quiet. Because almost always, I say to the defenders of “compliments”, not to say that always, when a man says something to you on the street is not because he wants to get to know you and know your human values, but because he wants to humiliate you. So, peace.

Originally posted on myFacebook wall.

Finalist of the Gabriel García Márquez Prize for Journalism in the Text category in 2016.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

You must be logged in to post a comment.