Censorship 2

Censorship and freedom of expression

Censorship and freedom of expression

In 2017 first, and then in 2019, authors Tom Secker and Matthew Alford obtained declassified documents from the CIA, the U.S. Department of Defense, and the National Security Agency detailing the extent to which these institutions were involved in American film projects

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

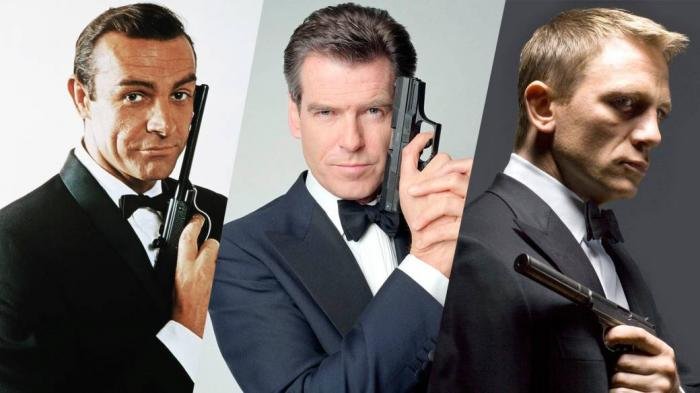

“There are themes that are not for laughs, neither are they for that school of filmmaking that brings Agent 007 to life.” Photo: Still from the Agent 007 films.

When James Bond producer Harry Saltzman seemed to be giving Costa-Gavras, after his first success, a blank check, saying: “What film do you want to make?”, he replied: The Human Condition, by André Malraux. The man cracked right there and then: “What? You need a lot of Chinese people, you can’t do that”, and closed the subject with a laugh.

Costa-Gavras confesses that at that time he was interested in films precisely about the human condition, about revolutions, daily struggles, the workers’ movement, the unions. At some point he worked on the project of making a feature film about Malraux himself, then deGaulle’s minister of culture.

There are subjects that are no laughing matter, nor are they for that school of filmmaking that gives life to agent 007. It’s risky to say the latter when thinking of Malraux, a man whose list of brave deeds, during the French Resistance and before, make him perfect legendary material for Ian Fleming’s literary creativity. However, I can’t imagine Bond writing something like The Human Condition. There is in the Anglo-Saxon character too much cheap philosophy, caricature of Nietzsche’s superman. Much less do I see Bond ending up being anyone’s minister of culture, no matter if it is the French warlord, or if it is Josef Stalin.

There is another more important reason that differentiates Malraux’s characters from Bond. The former seek with (futile?) desperation the simultaneous redemption and understanding of the sense of being in the face of the immeasurable anguish of having to kill. The latter assumes to his condition of existence a brute quality of polite murderer. It is known that originally the Bond character was to be a blunt weapon, lacking sophistication, with the mere function of murdering by the orders of another. That license to kill is really a license to carry out assassination orders and take the occasional macabre liberty.

The founding director of the CIA, Allen Dulles, was a friend of Ian Fleming. After the Bay of Pigs debacle, the agency sought in the fourth installment of the Agent 007 series of films, Thunderball (1965), a public relations operation to improve its image. It introduced a character, Felix Leiter, a CIA agent, as an empathetic character. The sympathetic agent, an employee of the agency promoting coups and political assassinations in so many parts of the world, lasts to this day.

In 2017 first, and then in 2019, authors Tom Secker and Matthew Alford obtained declassified documents from the CIA, the U.S. Department of Defense and the National Security Agency detailing the extent to which these institutions were involved in American film projects. The list totals 1,000 titles, including film and television material, and includes many of the most iconic products of American filmography.

According to Secker and Alford, in many cases, if there are “characters, scenes or dialogue that the Pentagon does not approve of, the filmmakers have to make changes to accommodate the military’s demands.” At the extreme, “producers have to sign contracts – production assistance agreements – that tie them to a version of the script approved by the military.” To make the reality even more interesting, in most cases, the agreements reached and the intervention of U.S. Government agents in a film product is confidential, protected by corresponding contracts. Not that they like it to be known out there that they are systemic censors, the public defenders of free speech: it is not a happy combination to support their employees or co-optees in other geographies as victims of censorship, and at the same time appear to cut scenes from films because the nuance is contrary to the imperial machinery.

In Goldeneye, Brosnan’s debut as Agent 007, an incompetent Yankee admiral who is killed by the bad guys, was not to the military’s liking; as a result, the unhappy character’s nationality was changed to Canadian and so appeared in the final product. In Tomorrow Never Dies, another installment of the British spy saga, some scenes were altered or deleted to please the uniformed censors. The CIA is more subtle (of course!), sometimes inserting its own employees in the writing of the scripts to avoid having to go under the knife later.

But beyond certain anecdotes, the involvement of imperial agencies is more systematic than cutting scenes or altering scripts. It is not just that “the idea of using film to blame mistakes on isolated, corrupt agents or bad apples, thereby avoiding any notion of systematic, institutional criminal responsibility, is straight out of the CIA and Pentagon manuals,” as Secker and Alford assert. The agencies of imperialism give made-in-U.S. entertainment an important role in their cultural warfare efforts at home and abroad. The envelope of their cultural hegemony is such that any attempt to limit the circulation of their productions in any country is quickly assailed as unacceptable censorship, totalitarianism and Orwellian action. Meanwhile, in the U.S., foreign film products have, in most cases, such a limited circulation that they are effectively invisible, let alone receive appreciable screen time for foreign materials depicting the imperial face of its foreign policy.

It is not, moreover, the more obvious, the more dangerous the subtlety. In many cases, most of the time, it is not a diabolical conspiracy to cajole the public. It is enough that the cultural material is an organic part of the symbolic reproduction of the system where it is produced. If the scriptwriter, the producer, the director and the director are imbued with the conviction of the cultural superiority of their society, there is no need for an obvious hand to force it, the colonizing instrumentalization of the product will occur without Orwellian interventions.

The Cuban obsession in the spy saga is marked in at least three films from three different periods. In the most recent era of the franchise, which began with Pierce Brosnan, one of the installments shows us scenes in a tropical Cuba with spy installations of absurd sophistication. Crowning the ridiculousness is having the womanizing hero have a sex exchange scene in a cliché beach house, not under the protection of air conditioning, but the flames of a fireplace, a perfect recipe for a steamy heart attack.

To reaffirm the obsession, the recently released last installation of agent 007, which ends the segment of Daniel Craig, who must be credited with having given the character new life with his acting quality, almost at the beginning has its Cuban scenes, in this case supposedly from Santiago de Cuba. Designed from the usual commonplaces when it comes to reflecting Cuba in the canned products of commercial cinematography. Who knows if someday we will find out about cut scenes and twisting of arms to the script by the efficient censors, paladins of freedom of expression as long as it is not about them. Maybe not, after all, those confidentiality contracts can be very persuasive.

When Facebook Censored the French Revolution

From the left

When Facebook censored the French Revolution

Liberty Guiding the People is one of the many posts that has suffered unbridled medieval voracity, typical of the old regime, on the part of the editors of the social network.

by Mauricio Escuela | internet@granma.cu

July 7, 2019 20:07:27

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Freedom guiding the people, the work of Eugène Delacroix in 1830, preserved in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

At the beginning of 2018, Jocelyn Fiorina, a French theater director, used Eugène Delacroix’s famous painting, Liberty Guiding the People, to promote her work Shooting in the Rue Saint-Roch. It was not at all a political message per se, much less pornographic, however, the image of the woman with her breast in the air (representing the ideals of the French Revolution), was censored by the social network Facebook.

Much has rained down on the streets of Paris since that July 14, 1789, which so many point to as the beginning of a new era. So much has happened since then, that our historical culture sometimes fails to recognize its origins, especially from the generation of contents that reread that past. Tons of books were written about the French Revolution, especially about that afternoon when Governor Lunay of the Bastille opened the doors of the fortress and surrendered. It is said that the king, buried in the palace, asked if it was a revolt. “No sir, it’s a revolution,” a minister told him.

Until that date, the meaning of the word revolution was linked to the movement of the stars, not even the commotion experienced by England in 1640 was considered as such; however, as the historian Alexis de Tocqueville later noted, the revolutionary current was a force that preceded in centuries to the seizure of the Bastille and that would succeed it forever, accompanying the imaginary and the movement of history.

REVOLUTION AND RESTORATION

Hanna Arendt, in her essay Conditions and Meaning of Revolution, points out that revolutionary intellectuals from 1789 onwards, including Americans who participated in the 1776 Revolution against the British Empire, would begin to detach themselves from the notion of “the new” that despite themselves [having been] brought about by the revolution. None of them, obsessed with the purity of the Goddess Reason, wanted to be involved as the architect of a change that also brought with it generalized periods of social terror, as described by Victor Hugo in his classic Ninety-Three.

According to those intellectuals, the revolt actually wanted to take the times back to a foundational and idyllic era, which supposedly existed, in which “the lamb slept next to the lion”. In fact, for them, the revolution was nothing more than a restoration, and thus the hairy ear of counter-revolutionary capital began to be admired in the vision of these early bourgeois historians, who feared the powder keg unleashed by themselves, with the help of the dispossessed and desperate people.

From then on, the bourgeois will begin to validate the king whose head it cut off, will speak of his nobility, as well as the spirit of matron and mother of Marie Antoinette. It is a re-reading of history that goes back to our days, in the figure of the politicians of the system, who celebrate the 14th of July [Bastille Day], but fear the demonstrations of young people who display the “three cursed words”: Equality, Freedom, Fraternity.

It so happens that, quickly, the new bourgeois order took hold of the feudal imaginary, and a new “ancien regime” began to live in modern societies. Bourgeois obscurantism sanctified, above all, private property and from there it built its notion of State, Law and civil society and, therefore, morality.

FACEBOOK AND THE OLD REGIME

Mark Zuckerberg must have been a very libertine student, during his time as a brilliant university student, taking the first tests of what was then the most extensive (and dangerous) social network in history. Judging by the number of insubstantial advertisements that fall under the censorship label of “pornography,” we read a certain obsession with the pleasures of the flesh, perhaps due to knowing them too much.

The truth is that Liberty Guiding the People is one of the many posts that suffer the unbridled medieval voracity, typical of the old regime, on the part of the editors of the social network. Facebook’s will to restore was evident during the exchange of messages between the editors and the director of the play. “When I appealed this absurd decision, the representatives of the social network assumed this censorship and said that, even in a 19th-century painting, any nudity is inadmissible…,” Fiorina told the press. The post was only unblocked, after the artist made a second version from the use of Photoshop, placing a poster of “censored by Facebook”.

It is no less alarming that those who monitor the use of the most used platform around the world not only do not know the painting, but also the historical fact and its meaning.

REVOLUTION AND EROTICISM

The upheavals of 1789 not only liberated the productive forces and brought a new rule of law, but also established a different morality, in which the body played an active role, as well as the nakedness of those parts that expressed the earthiness of man and woman. Most artists, starting with the French Revolution, would not only paint scenes of it, but would also mix eroticism with freedom, almost as synonyms.

It was the historical change that art needed to get rid of medieval censorship, the artist creates from what he [or she] feels and what he [or she] thinks, in a revolutionary dynamic that was not seen with good eyes either by the current critics. In fact, throughout the nineteenth-century, schools and authors were pondered that today nobody mentions. It was an attempt to restore medieval censorship, to take back that narrative, that of the arts, to the old regime that the bourgeoisie evoked to appease the genius summoned by itself.

No wonder, then, that Facebook, a private company that supports conservatism and still aspires to restoration, censured Delacroix. So far does the desire to restore the social network go that a Venus de Willendorf, a Paleolithic sculpture, was even blocked. Without a doubt, Facebook and Zuckerberg would have been excellent platforms not for restoration, but for the medieval witch-hunt, the Inquisition index or that modern version of totalitarian dystopia, the novel 1984. And there are still those who describe the social network and its publishers as revolutionaries.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 | |||||

You must be logged in to post a comment.