Simone de Beauvoir

Simone de Beauvoir

A tireless fighter for women’s rights

Symbol of the and militant protesting woman of the feminist movement, the French novelist visited Cuba and, hand in hand with its main leaders, learned about the Revolution and the role of the so-called weaker sex in the emerging Caribbean social process.

By Javier Gómez Lastra

May 26, 2016

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

“The fact that determines the present status of women is the stubborn survival of the oldest traditions in the new civilization being outlined. That is what is unknown to hasty observers who see women as inferior to the opportunities offered to them today, or who see only dangerous temptations in those opportunities. The truth is that her situation lacks balance, and for that reason it is very difficult for her to adapt to it. (…)

“The fact that determines the present status of women is the stubborn survival of the oldest traditions in the new civilization being outlined. That is what is unknown to hasty observers who see women as inferior to the opportunities offered to them today, or who see only dangerous temptations in those opportunities. The truth is that her situation lacks balance, and for that reason it is very difficult for her to adapt to it. (…)

“Everything still encourages the unmarried young woman to expect ‘Prince Charming’ fortune and happiness rather than to attempt the difficult and uncertain conquest alone. In particular, it will give her the hope of reaching a higher social stratum than her own, a miracle that will not reward her life’s work. But such hope is dire, because it divides their energies and interests; it is a division that is perhaps the most serious disadvantage for women. The parents still educate the daughter with a view to marriage more than they promote her personal development, and the daughter sees in it so many advantages (…)”.

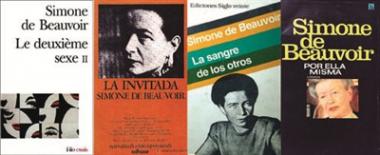

This text, taken from the work “Le Deuxième Sexe” or “The Second Sex” by Simone de Beauvoir, a French writer, narrator and philosopher and an essential figure in 20th-Century literature and thought, was a theoretical starting point for various feminist groups and became a classic work of contemporary ideology.

The piece, which breaks the existing canons in Europe since the Second World War, tells a story related to the social status of women and analyzes the different characteristics of male oppression.

It also exposes the gender situation from the point of view of biology, psychoanalysis and Marxism, and destroys the existing feminine myths, inciting the search for the authentic and full gender liberation.

Considered ambitious, the text also maintains that the struggle for women’s emancipation is different and parallel to that of the classes and that the main problem to be faced by the so-called weaker sex is not the ideological but the economic front.

The publication evoked strong reactions because of the marked character of nonconformity that the women of that time began to show.

The big push for gender equality

The beginning of the second half of the 20th century had very particular characteristics in the socio-cultural field in Europe. If anything brought about radical changes in ethical, political and philosophical thought in the countries of the Old Continent after the World Wars, it was the enormous need to achieve fundamental human rights and the emancipation of women.

Faced with the example of the policy of equality for all, applied by the governments of the nations of the newly created socialist bloc, many thinkers, human rights fighters, writers, poets, philosophers, and even politicians in Western Europe took a 180-degree turn in their way of valuing life and began to call for true equality between men and between men and women.

It was in this context that Simone de Beauvoir stood out and left a deep mark on the universal history of the world, leaving behind not only her extensive literary work, but also her tireless struggle.

In spite of her bourgeois origin, from a very young age the intellectual knew the difficulties of her contemporaries in a world dominated by men, markedly masculine, made in the image and likeness of the male and where women were relegated to domestic chores or simply to love.

Her work reflected women’s problems, marked by exclusion from production and home-based processes and purely reproductive functions, which represented the loss of all social ties and the possibility of being free.

A radical change

Simone was born in Paris on January 9th, 1908, in a district where coffee shops were beginning to proliferate, where literary gatherings were present and intellectual environments that logically influenced the writer’s education were created.

Very early on she excelled as a brilliant student and studied philosophy at the Sorbonne. Until 1943, she was involved in teaching in high schools in Marseille, Rouen and Paris.

At the age of eighteen, she wrote the first literary essay where the protagonist has many traits in common with her. From that moment on, literature played an essential role in her work.

In 1929 he met the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, who became her companion for the rest of her life. Together they shared almost five decades of existence.

Sartre’s influence was unquestionable and Simone began to make use of her existential freedom. This led her to renounce her family and friends, adapting to the real world and choosing a new system of life based on her encounter with the philosopher.

Under these principles, she managed to penetrate the world of the Parisian intellectuals of the 1930s, being one of the few women that this closed universe came to accept.

Extensive literary legacy

Extensive literary legacy

According to the vast majority of critics, researchers and scholars of Simone’s literature, in her literary texts she dared to revise the concepts of history and character and incorporated, from an existentialist perspective, the themes of freedom, situation and commitment.

Together with Sartre, Albert Camus and Merleau-Ponty, among others, she founded the magazine Les Temps Modernes [Modern Times], whose first issue was published in October 1945 and became a political and cultural reference point for French thought in the mid-20th century.

The thinker’s extensive work includes the texts “The Guest” (1943), “The Blood of Others” (1944), “Pyrrhus and Cinema” (1944), “All Men are Mortal” (1946), “For a Morality of Ambiguity” (1947), “America Today” (1948) and “The Farewell Ceremony” (1981).

In the latter, she openly dealt with the curious love relationship, from her youthful days to her old age, and the death of her companion, which implies their hard separation. Despite the absolute identification between them, they never shared the same roof, making use of freedom and with no other purpose than the mutual need to find each other, which allowed them to achieve a perfect symbiosis.

The work ends with the striking phrase: “His death separates us. My death will not bring us together, it is so. It’s been a long time since our lives could have melted together.

In the mid-twentieth century, with some feminists, she also established the Women’s Rights League, which set out to react firmly to any sexist discrimination, and prepared a special issue of Modern Times to discuss the subject.

Her many testimonial and autobiographical titles also included other texts such as “Memoirs of a Formal Young Woman” (1958), “The Fullness of Life” (1960), “The Power of Things” (1963), “A Very Sweet death” (1964), “Old age” (1968), “The End of Accounts” (1972) and “The Farewell Ceremony” (1981).

Character is destiny

The Algerian war broke out in 1954 and Simone felt powerless in the face of reality, thus beginning her period of political struggle.

She took part in anti-fascist demonstrations and gave lectures to the students, but all attempts to impose criteria against the system were unsuccessful, and, despite her efforts, Charles de Gaulle was declared President of the Republic.

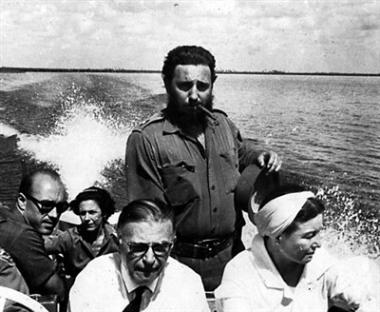

This new political situation prompted Simone to rekindle the need to rebel once again, and she agreed to accompany Sartre to Cuba in 1960. There she met Fidel Castro and Ernesto Che Guevara, among other revolutionaries, in Havana. Cuban photographer Alberto Korda documented the meeting between the couple and the two leaders.

Both Sartre and Simone were always fascinated by the Heroic Guerrilla. At the time of his death, seven years later, Sartre wrote: “Che was not only an intellectual, but also the most complete human being of our time”.

The couple spent almost two months working on the main island of the Antilles, which led to their subsequent and continued dedication to the defense of the Cuban Revolution.

They made an intense tour of the island, which included a tour of the Ciénaga Zapata swamp, the inspirational examination of the book “Sartre Visits Cuba”, published in Havana in 1960 by Ediciones Revolución. In its pages, the philosopher narrated his experiences in the country.

Fundamental decade for women and their rights

The Frenchwoman’s ideas soon reached the rest of the world and Simone de Beauvoir centers began to proliferate everywhere.

The emancipation of women was her ideal of struggle. Without denying the biological differences, she was able to denounce a whole system of oppression that worked – and still persists – from levels such as the home and that can extend to entire nations where one sex is established and dominated by another.

Her main ideology was based on equal opportunities for both men and women and on the true emancipation of all, both at work and in society.

Simone disappeared physically in 1986, but her intense work of ideological activism and broad literary exercise remain imperishable as a sure guide to the struggle for full equality. This is what her work testifies to.

You must be logged in to post a comment.