Translations 677

Alejandro Armengol

Alejandro Armengol

About Me

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Alejandro Armengol was born in Cuba and has lived in the United States since 1983. He studied Electrical Engineering and Nuclear Physics in the University of Havana, and holds degrees in Psychology and Sociology, two professions he has never practiced. A journalist for more than fifteen years, his work has been published in journals and newspapers in the United States and Europe, and some of them have received the National Association of Hispanic Publications award. He writes a weekly column in El Nuevo Herald and another in the online newspaper Encuentro en la red. He is an associate professor in the University of Miami. In 2000 he published his books La galería invisible (short stories) and Cuaderno interrumpido (poems), and in 2003 his book Miamenses y Más. You can write to him at aarmengol@herald.com

I received clarification from the State Department’s Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs about the statements made by Thomas Shannon, Assistant Secretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs, incorrectly published by the news agency EFE since the very beginning, as I said both in my blog and my Monday column.

It only remains for me to add that, even if it comes out on Monday, I write my column on Thursday or Friday, so that the relevant page in El Nuevo Herald is ready for print right on Friday. I had not come to the newspaper since last Thursday, so I have just found out about this information, which I now pass on to the readers of my column and to Cuaderno de Cuba:

In his “retirement”, Fidel swims, writes, reads the papers and studies Darwin

Clarín

In his “retirement”, Fidel swims, writes, reads the papers and studies Darwin

By Hinde Pomeraniec

December 3, 2009

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

All the news we’ve had until now about Fidel Castro’s condition after almost three years of nonstop surgery and illness were his photographs with various heads of State and the articles he writes for the Cuban press on a regular basis. On Saturday, the Argentinean political scientist and sociologist Atilio Boron was in for a surprise while having lunch at a restaurant in Havana: someone came to tell him that Fidel would receive him that day at 5 p.m., so they would come to pick him up in a little while. Two days later, Fidel wrote about their one-hour-and-forty-minute-long meeting and sang the praises of a paper Atilio had presented in a conference of economists. At a later date, Mr. Boron gave Clarín unheard-of details about Castro’s daily life and the conversation they had in a place hitherto undisclosed.

“Truth is, I thought I would see a disabled person, but what I found was quite the opposite: he had a very good color and muscle tone, which I could check for myself in his handshake and hug when we said goodbye to each other”, Boron recalls. It was a summer afternoon, and Fidel was wearing the typical uniform of Cuban athletes, except for the short pants that revealed “very strong legs, a sign that he’s following his therapist’s instructions to the letter. He looks very bright”.

Fidel is not at a clinic, but in a house fitted with medical equipment for emergencies and facilities to move around and work out, and even a small pool where he can swim. He receives few visitors, his contacts with officials limited to “one or two meetings with Raúl”. You don’t see many people working in the house; he’s the one who seems to be working hard as befits “a soldier in the Battle of Ideas” and very happy and relaxed for not being in power.

We met in a living room where there was a desk, a run-of-the-mill PC, no cell phone, and the folders with clippings he’s always kept near since he was President. Boron also noticed a number of blue notebooks, organized by topic, where Fidel writes his reflections. And what about the voice of the great speaker who would talk to his audience for hours on end? “He’s never been one for speaking in a loud voice, on the contrary: he spoke slowly, still his usual self, a Fidel who chews on his every syllable”, Boron assured, adding that Fidel drank nothing nor was ever interrupted to take any medicine.

Always on top of current events, in the days of Darwin’s anniversary Castro reads his work while devouring what text on nanotechnology he can get his hands on. The chat with Boron centered on the economic crisis, and Fidel said he was worried about what he believes its great impact on the region will be like. “He thinks the continent’s certain shift to the left in the last few years will be compromised. Fidel understands the circumstances very well and fears the right will have a new lease on life”, he explained.

Did you talk about President Kirchner’s visit?

Yes, and he said to be quite impressed by how energetically she defends her positions. We also talked about the problems in the countryside, and he was shocked at the way it happened and as much concerned about the consequences as he was about other issues, for instance, Paraguay, as he believes President Lugo has many obstacles in his path.

Did you talk about the United States?

I’ve got the feeling he has taken a certain liking to Obama, but without building his hopes up too much. He said, “Obama will soon learn that the Presidency is one thing, but the Empire is another matter altogether”.

Your meeting took place at the end of a very hectic week in Cuba when changes were made in the government…

He started to talk about that and nothing else, going into greater detail about what he had already said that the enemy outside had built up their hopes with these officials, but it was made clear that what he meant was that Cuba’s enemies had raised their hopes over them. He mentioned they had made mistakes, sometimes because of excessive political ambition or personal impatience…

To get an idea of Fidel’s condition –keeping in mind that he’s almost 83– Boron points out that he can walk without anybody’s help and had even taken a stroll around the surrounding area a few weeks ago, alone and under no escort, to buy a newspaper. He was standing in line like any other Cuban and, they say, a woman recognized him and a small urban tsunami of emotions broke out in that Cuban neighborhood.

Woman and Violence

Women and Violence: A Community Health Problem?

By Alexis Culay Pérez, Félix Santana Suárez, Reynaldo Rodríguez Ferra and Carlos Pérez Alonso

SOURCE: Rev Cubana Med Gen Integr 2000;16(5):450-4

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

ABSTRACT

A descriptive horizontal study was carried out to learn the behavior of violence against women in the micro-district “Ignacio Agramonte”, of the “Tula Aerie” Policlinic in Camagüey. The period studied was from August 1st, 1997 to January 31st, 1998. From a total of 1088 women between the ages of 15-49, 310 were chosen to conduct a survey. The size of the survey was calculated using the well known statistical program EPIDAT. The results of the survey showed that 226 women reported some type of violence. This is 72,9% of the women interviewed. Psychological violence was reported by half the women, sexual violence by a third and physical violence was the least reported. The majority of women who reported violence were 30-39 year-old women with high school education. The great majority of the women victimized didn’t request professional help.

Gaceta Médica Espirituana 2008; 10(2)

Original paper

Medical Faculty “Dr. Faustino Pérez Hernández”

Family violence and adolescence

By Dra. Help Walls García1, Dra. Anabel González Muro2, Dr. Jorge Luis Toledo Prado3, Dr. Ernesto Calderón González4, Dra. Yurien Negrín Calvo5

1 First grade Specialist in Child Psychiatry. Adjutant Professor, Resident MGI

2 First grade Specialist in General Psychiatry. Adjutant Professor

3 First grade Specialist in General Psychiatry

4 First grade Specialist in MGI 5

A CubaNews translation by Giselle Gil

Edited by Walter Lippmann

ABSTRACT

Due to frequent reports of family violence against adolescents received at Clinic No.29 of the Sancti Spíritus Area Mental Health Community Center a research was carried out. The main objective of this study was to describe some of the characteristics of family violence. A horizontal descriptive study was made which included 63 adolescents between the ages of 10-18. We calculated the violence frequency as well as that of age and sex, abuse types, parent-child relations to the victim, symptoms associated with abuse and if the family is conscious of this violence. Results showed a high percent of family violence towards girls and towards children in the 13-15 year old group. Violence was found to be mostly psychological rather than physical. We also found mothers are more violent and that low self esteem and aggressiveness are the most common symptoms. Only a low percent of the families were aware of being violent. Based on these results we made a proposal to investigate this problem further in the different health areas. Further study will also help design community intervention strategies to eliminate or reduce this violence that affects adolescents and the rest of the family.

Is family violence, a health problem?

By Dr. Mario C. Muñiz Ferrer, Dra. Yanayna Jiménez García, Dra. Daisy Ferrer Marrero and Prof. Jorge González Pérez

A CubaNews translation by Giselle Gil

Edited by Walter Lippmann

ABSTRACT

A descriptive study of the results of the test “what I don’t like about my family” was carried out with the objective of studying family violence and how to confront it in a health area. The test was applied to 147 5th and 6th grade children studying in the “Roberto Poland” School located in the “Antonio Maceo” neighborhood of the municipality of Cerro. The different types of family violence were classified and grouped by incidence frequency. Family violence prevalence was also calculated, as well as its possible relation to drinking. The results allowed us to establish that family violence is a health problem and that it is related to the intake of alcoholic beverages.

INTRODUCTION

One of the most pressing problems that humanity faces in the XXI century is violence. We live in a world in which violence has become the most common way of solving conflicts. Today it is a social problem of great magnitude that systematically affects millions of people in the whole planet in the most diverse environments, without distinction of country, race, age, sex or social class.

Psychological gender violence is a covert form of aggression and coercion. Because its consequences are neither easily seen nor verified, and because it is difficult to detect, it is more and more used. Its use frequently reflects the power relationships that place the masculine as axis of all experience, including those that take place inside the family environment.1

Psychological gender violence expressed in the family environment acquires different shades depending on the context in which it takes place. In a rural environment, we generally find families with specific characteristics such as low schooling, resistance to change, inadequate confrontation and communication styles. All this favors the stronger persistence of patterns belonging to a patriarchal culture in this area rather than in urban areas, and therefore, women become victims, especially of violence.2

Cuba has a large population in urban as well as in rural areas, and so doesn’t escape from this reality (that of feminine victimización), even when our social system contributes decisively to stop many of the factors that favor violence against women. Also, we have propitiated substantial modifications of the place and role of the family as a fundamental cell of society. But, even today, we haven’t achieved a radical reorganization of the patriarchal features present in the national identity or on socializing agents like family.

The Novel of His Memories

The Novel of His Memories

Author: Fidel Castro Ruz

17 de abril de 2014 21:33:15

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

SOURCE: Granma Internacional. 08/12/02 page 8

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

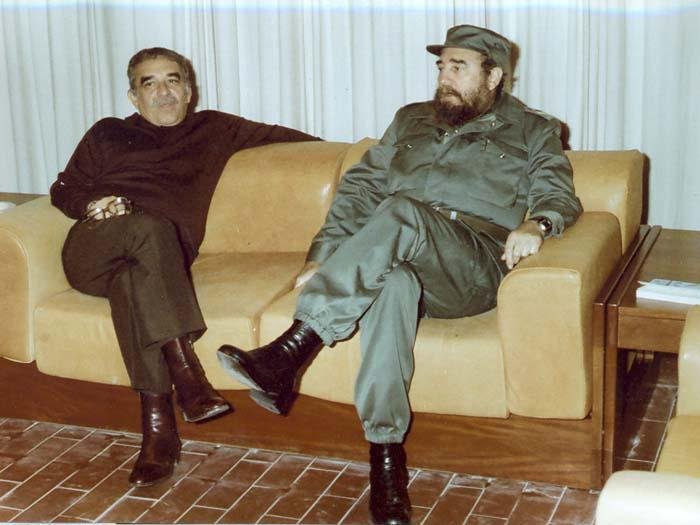

Gabo and I were in the city of Bogotá on the sad day of April 9, 1948 when [Colombian Liberal leader and presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer] Gaitán was killed. We were both 21-year-old Law students and witness to the same events. Or at least that’s what we thought, because neither of us had heard of the other. We were complete strangers, even to ourselves.

Almost half a century later, Gabo and I were chatting on the eve of a trip to Birán, the place in eastern Cuba where I was born in the early morning of August 13, 1926. Our meeting had the hallmarks of those intimate, family-like occasions when you swap reminiscences and fond memories in a warm atmosphere that we shared with a group of Gabo’s friends and some of my fellow leaders of the Revolution.

That evening I went over the images engraved in my mind: ‘Gaitán is dead!’, were the words on everyone’s lips that April 9 in Bogotá, where I was together with a number of other young Cubans to organize a Conference of Latin American students. Baffled and stock-still, I gazed at a crowd of people who were dragging the killer along the streets while others set fire to stores, office buildings, movie theaters and tenement houses, and still others were carrying pianos and cupboards on their shoulders. I could hear the sound of glass being shattered and posters being torn. From street corners, balconies full of flowers and smoldering buildings further away, voices shouted in frustration and grief. A man was venting his anger by banging his fists on a typewriter, and to spare him the bother of such a colossal, unusual effort I took it away from him and threw it hard against the cement floor, where it smashed into pieces. Gabo was listening as I spoke, probably taking my words as proof of his assertion that very few Latin American and Caribbean writers have ever needed to invent anything because here fact is stranger than fiction, so maybe his biggest problem has been how to make his own reality credible. The main thing is that, near the end of my story, I was surprised to hear that Gabo had been there too, a coincidence I found revealing in that we had perhaps walked down the same streets and lived through the same frightening, astonishing and urging experiences that made me be a part of that stormy sea of people who suddenly came down the surrounding hills. So I shot the question with my chronic curiosity. “And what were you doing during the Bogotazo[1]?” Unruffled, entrenched in his remarkable, lively, unruly and exceptional imagination, he smiled at me and replied with the clever, emphatic spontaneity of his metaphors: “Fidel, I was that man with the typewriter”.

I have known Gabo for a very long time, and we may have first met at any moment or place of his luxuriant poetic geography. As he admitted himself, he has on his conscience that he had initiated me into, and kept me up-to-date on, “the addiction to speed-reading bestsellers as a purification method against official documents”, to which we should add that he’s responsible for convincing me not only that I would like to be a writer in my next reincarnation, but also that I would like to write like Gabriel García Márquez, gifted as he is with a headstrong attention to detail on which he builds, as if it were the philosopher’s stone, all the credibility of his dazzling exaggerations. He even said once that he saw me eat eighteen scoops of ice-cream at one sitting, something that I denied emphatically, as you might expect.

Then I remembered a time when, after reading the preliminary text to Del amor y otros demonios (Love and other demons) –where a man rides his eleven-month-old horse– I suggested the author: “Look, Gabo, put two or three more years on that horse, because at that age this one’s still a foal”. Later on I read the printed novel, and what comes to mind is a passage where Abrenuncio Sa Pereira Cao, whom Gabo describes as the most notable and controversial physician in the city of Cartagena de Indias at the time the story is set, is sitting on a stone by the side of the road, crying next to his dead horse, who would have been a 100 years old come October but whose heart had stopped as they were coming down a steep descent. Gabo, as expected, turned the animal’s age into an exceptional circumstance, an incredible happenstance of indisputable truthfulness.

His books are irrefutable evidence of his sensitivity and steadfast adherence to his roots, the inspiration he draws from Latin America, his loyalty to the truth, and his progressive thoughts.

We share an outrageous theory, likely to sound godless to academics and men of letters, about the relative nature of words, and I stick to it with as much passion as I feel for dictionaries, especially one that he gave me for my 70th birthday, a real gem in which every definition is followed by famous quotations from Spanish American writers as examples of the proper way to use your vocabulary. Besides, as a public man obliged to write speeches and recount events, I share with this renowned author what you may call an endless obsessions: we both take great pleasure in looking for the exact word until the phrase turns out the way we want, faithful to the feeling or idea we wish to convey and always from the premise that it can be improved. I admire him most of all when he simply invents a new word if the right one doesn’t exist. How envious I am of such liberty!

Now Gabo writes about Gabo: he has published his autobiography, that is, the novel of his memories, a work that I believe stems from nostalgia for the four o’clock thunderclap, the instant full of bolts of lightning and magic that his mother Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguarán missed when she was far from Aracataca, the unpaved hamlet of never-ending downpours, alchemists, telegraph, and the stormy sensational love affairs that would impregnate Macondo, the small town in the pages of one hundred lonely years, with all of Aracataca’s dust and charm. As a token of our old and warm friendship, Gabo usually sends me his manuscripts, much as he sends his rough drafts to other dear friends of his as a gesture of kindness and unaffectedness. This time, he delivers himself with honesty, innocence and energy, the qualities that disclose what he really is: a man with the goodness of a child and infinite talent, a man of tomorrow whom we thank for the things he’s been through and for having lived to tell the tale.

[1] The Bogotazo refers to the massive riots that followed the assassination of Gaitán.

Today’s youth… lost?

Today’s youth… lost?

Author: Leticia Martínez Hernández

May 22, 2009

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

I admit it: it bothers me when my generation is called into question, not taken seriously and, worse yet, branded a lost cause, a very good reason to annoy the most even-tempered of souls, of which I am one. Is the word ‘lost’ by any chance synonymous with irreverent, revolutionary, nonconformist, impetuous, determined…? I don’t think so.

I admit it: it bothers me when my generation is called into question, not taken seriously and, worse yet, branded a lost cause, a very good reason to annoy the most even-tempered of souls, of which I am one. Is the word ‘lost’ by any chance synonymous with irreverent, revolutionary, nonconformist, impetuous, determined…? I don’t think so.

A few days ago I took a bus, a bag hanging on my shoulder. Just by chance I found an empty seat beside a boy wearing the latest styles, tattoos and earphones included, who was also carrying something.

As chance would have it, we got off at the same stop, and I felt a great sense of relief when he insisted on helping me down the steps of the rear door with my load, his own notwithstanding. Like a harbinger of doom, the gloomy phrase suddenly came to me, as did memories of so many other boys and girls in their twenties who would leave more than one skeptic at a loss for words, and some who do give their nitpickers cause to complain.

Should we call lost those youths who stormed into the Isle of Youth, Pinar del Río, Holguín, Las Tunas and other Cuban provinces to share the pain of –and ease the burden on– the victims when the heavy rains and strong winds laid into Cuba last September? Or those who for the first time got their hands dirty trying one way or another to reap some benefit from the wounded land? I remember some of tem doing their best to make sad children laugh while their own family had no roof over their heads.

And the thousands of young Cubans who keep our education system going today, are they also the target of those fire-and-brimstone statements? Do the skeptic know anything about the nights those youths spend preparing their lessons while others their age are having great fun at a party; about how nervous they are on their first day in front of a class; about how they puff up with pride to be teachers even before their twentieth birthday; about the overwhelming burden that mistrust places on their shoulders?

Would the word ‘lost’ apply to those boys and girls who ache for their faraway loves as they stand day and night on our coastal reef to watch over every stretch of this country? If they only knew about Lester and his stubborn patrolling along some far-flung beach of Guantánamo province, or about Javier’s great responsibility for a radar who does nothing but sweep the sea surface!

A colleague heard of the paper I work for and asked my age right away: “And at 25 you’re already writing for Granma?” I had to summon up my patience for a long while –someone else said once that we were being ripened with carbide– before I told him of so many others like me he could find walking the halls of the official organ of the Communist Party of Cuba, where they spend countless hours waiting for closing time or hunting for the best thesis to finish a report while listening to [Cuban folk singer] Silvio, taking a few dance steps or exchanging jokes.

Have the doubters forgotten the exploits of those beard-wearing boys who cut their way through the bush in the Sierra Maestra Mountains and then raided our cities to disrupt the existing order inside Cuba and out? If a brilliant man like Fidel has always trusted in our youth’s creative strength, why are there others who allow themselves the luxury of casting a shadow over them? We could fill endless pages with stories of young people who are underestimated on arguments as flimsy as their lack of experience. How different everything would be had the pioneers of this Revolution waited for the lazy, slippery experience…!

It’s true that things are different now and it’s no longer our role to be heroes in the crossfire, but the bullets now aimed at our heads are far more dangerous. Today’s average youth must place limits on their aspirations, chances of personal fulfillment and even opportunities to have fun at the same time as they are showered with deceitful canons designed to convince them there’s a better way of life outside our country. And despite the few who may fall for the swan song and others who allow despondency to get the better of them, millions remain who refuse to give in and still fight for their homeland’s future.

What do they mean then by saying that youth, my youth, is hopeless? That we wear provocative and stylish clothes, live noisily, say what we think without a second thought, dream of possible and impossible things, dare to take on responsibilities we have no idea we can ever fulfill, never wait until tomorrow to pledge our commitment to the future… ? If these are the answers, then not only are we lost, we don’t want to be found.

All The Absences/About Exile and Other Abductions

All The Absences/About Exile and Other Abductions

Or It Fits If It Fits

By Kobo Abe

The Woman in the Sand

Loneliness is a Thirst that Illusion Cannot Satisfy

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Synopsis:

Ely, the wife of the “Godfather of Havana” undertakes the odyssey of leaving Cuba with her family at the start of the 1980s. An almost complete spectrum of the psychology of Cubans who have decided to leave (or not) parades through her home: marriages to former political prisoners; the months during the Mariel boatlift; the discrimination and ignorance that accompanies her; the opportunism; the avarice; the betrayal; the selfishness; and, on top of all that, the implosive nature of familial love, offered friendship, solidarity, genuine apathy, spontaneity, and genuine human interaction. The best, the worst and the moderate aspects of Cuban idiosyncrasy overwhelm Ely’s life, and are reflected in her family, friends and acquaintances, who parade through a text that is constructed with every page. The story of the internal and external exile of these characters incites us to change the gestalt, to identify with the whole as well as its parts; it constitutes a swipe to those who emigrate, about the challenges and the price of existence regardless of circumstance, and how the fruits of that existence cannot calm the strange thirst that illusion is unable to quench, according to the preface written by Japanese author Kobo Abe at the beginning of this novel.

Silvio Rodriguez calls for Cubans to Enter and Leave Cuba at Will

Silvio Rodriguez: Cubans Should be able to Enter and Leave Cuba at Will

By Adrián Leiva

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Silvio Rodriguez calls for the right of all Cubans to be allowed to enter and leave their country at will

The news that Cuban singer-songwriter Silvio Rodriguez was denied a visa to enter the United States to attend a tribute to U.S. musician Pete Seeger prompted a letter that was published in the Dominican press. The letter, which was addressed to Rodriguez, was written by a Cuban residing in the Dominican Republic. Rodriguez quickly responded to the letter; the content of both letters is published below.

An open letter to singer-songwriter Silvio Rodríguez, Published in the newspaper El Nuevo Diario, Dominican Republic, on Sunday, May 10, 2009

The person writing this is Cuban just like you. First, I support you in your complaint against the U.S. officials who denied your request to legally enter the U.S. to attend the tribute for Pete Seeger. It’s a loss to all that you were unable to play your music during the celebration that took place in New York city. Like most Cubans, I too resent those foreign laws created to threaten the sovereignty of the Cuban people.

Now that we have established that, I want to share with you a another reality that is even sadder than the fact that a country’s officials refused a foreigner’s request to visit their country.

Over the past 50 years, thousands of Cubans have been unable to enter Cuba, not even to attend the funeral of loved ones as close as a mother or a son. Among these are musicians, artists who have settled abroad for the sake of their careers, and who are prevented from reentering their own country despite the fact that they have praised Cuba at every turn. Celia Cruz is a classic example.

My mother is 80 years old. I’m prevented from entering Cuba to see her, which means that my human rights have been trampled as badly and as unfairly as yours. You are no threat to the United States or its society. Likewise, I’m no threat to Cuban society. Neither of us is a terrorist or a murderer.

You can’t cloak justice in political ideology. There is only justice. The first and most important belief is that all human beings are entitled to their respect and their dignity.

Unfortunately, our native land practices a policy called a “permanent exit,” and it’s an inhuman abomination. It is anti-Cuban and a threat to the legacy of our Mambi ancestors, who fought for Cuba’s freedom so that all Cubans could enjoy the fruits of a free society. They were guided by Marti’s dream of a country “for all, and for the good of all.”

Silvio, my countryman: my freedom ends where yours begins. One must give respect to earn respect; rest assured that I write these words while holding you in the highest respect as a human being and a fellow Cuban. By the same token, I would expect you to do the same for me. It is with this in mind that I now approach you as an artist who is known for having dedicated his life to promoting social justice and progressive ideals during these turbulent historical times in which we live.

I ask that you use your voice and your guitar to intone a song promoting harmony and a respect for diversity between all Cubans. Sing for the unification of divided Cuban families and for the repeal of this harmful “permanent exit” policy that is a shame to the sacrifices made and the blood spilled by our ancestors. I am not asking you to sing a song of protest. I would rather that you make it a love song that should touch the hearts of all Cubans, especially those which most need to hear it.

If you want, invite other artists to sing along with you, anyone who might be sympathetic to the cause of those who cannot be there. Sing for those of us who are absent by necessity, but who hope to one day return to sing at your sides. Invite Fito Páez, Ana Belén, Serrat, Pablo, Chico, Mercedes Sosa, and anyone else who wants to open their hearts to this endeavor. Sing for the freedom and the right for all Cubans to be able to spend time in our native land.

Written by: Adrián Leiva

An open response to Cuban citizen Adrián Leiva.

Havana, May 10, 2009, 5:00 p.m.

Mr. Adrián Leiva:

To begin with, I’ve made no complaint about being denied entrance to the United States. I just sent an email to my sister in which I told her that since I had not yet received a visa to travel to the United States to attend the tribute to Pete Seeger to which I had been invited, I would simply return to Cuba to continue work. The organizers of the Seeger tribute asked her permission to publish the email, so we gave it to them. That’s why this came out. About two days later, during the tribute, I wrote to the Maestro Seeger directly and asked him to forgive my absence even though I had originally pledged that I would be there. I explained to him—as well as I could and to my understanding—why I could not keep my word to him. Somehow the press somewhere got hold of the letter, resulting in all this controversy.

However, I understand; I’ve spoken out about what I consider to be an error in our migration policies, like the so-called “white letter” and the fact that permission is needed to enter and leave our own country. It’s an archaic policy that is obsolete and should be repealed. I am convinced that when that absurd obstacle is removed, our country will be a better place and we will all feel better about it and one another.

I can’t promise I’ll write a song about it, because, quite frankly, I’m not alone when do that—I do rely on the Muses as well. But I will promise you this: no matter where I am, I will continue to promote the belief that Cubans should have the right to enter and leave their country at will, providing, of course, that they do it legally.

Silvio Rodríguez Domínguez.

Postal Service Talks

Postal Service Talks

By Dr. Néstor García Iturbe

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

September 19, 2009

Very interesting, the statement issued by officials from the U.S. State Department on September 18 about talks aimed at resuming direct postal service between the United States and Cuba.

According to the note, they are very pleased with the initial discussions of a first round of conversations that the U.S. government considers to have been positive, after a one-day meeting where a variety of issues related to transportation, quality and security of mail service between both countries were covered.

Since these first talks were held in Havana, the Cubans offered the U.S. delegation an opportunity to tour a Cuban mail processing center and post office, and the U.S. officials offered to reciprocate the tour with a visit to an international processing center in the U.S. when the Cubans travel to their country to resume talks, which both sides agreed after consultation in their respective capitals on the issues raised.

So far, so good… Problem is, the spokesman could not help seizing the opportunity to try and do Obama a little of much-needed credit.

What’s behind the Obama administration’s efforts to re-establish direct postal services between the United States and Cuba?

In words of the spokesman, “establishing direct mail service supports President Obama’s goals, as announced April 13, of bridging the gap among divided Cuban families and promoting the free flow of information to the Cuban people”.

I’m convinced that in the meeting with the Cuban postal authority, the U.S. delegation failed to give a correct explanation as to the whys and wherefores of their goals, as unlikely to have been addressed in the first meeting as it will be in the next ones.

Who keeps open the gap dividing Cuban families? Who prevents the Cuban people from being properly informed?

Two issues deserving long talks with any U.S. delegation, be it under Clinton, Bush or Obama, the president of the moment. Those who encourage Cubans to leave by illegal means, maintain the ‘dry feet, wet feet’ law, and have extended the commercial blockade to apply as well to culture, information and every aspect of life in the Island have very few arguments to discuss these matters with Cuba.

Mirrors

Mirrors

By José Alejandro Rodríguez

August 29, 2009 23:26:55 CDT

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Unlike the deceiving mirror of my childhood, which assured the witch she was the most beautiful woman in the world, ordinary mirrors are built with the quicksilver of truth. They reflect our image such as we are, with the furrows and the snow of time.

Societies also need mirrors to scrutinize their images, to detect wrinkles, which, conversely to those that mark human faces, can be reversed. And, our socialism needs to be systematically observed, to avoid clinging to idyllic images, or deceiving notions that we are living in the best of all possible worlds.

I say this because, in my long and loving job of reflecting our society’s problems, to guarantee that it lasts longer; I have met a blinding resistance to my sincere criticism. This resistance takes the form of a “handsaw”; meaning that those who judge me, are carving a hole on the floor for me to fall through.

The sick obsession with protecting “the image” of the country, of the ministry, of the company or of the territory is more frequent than concern for the real messes being reported. On occasion, it is paranoia trying to protect positions, jobs, and other trifles, when improving reality is what it’s about.

Other times, it’s the consequence of a confusion many people have. They think that problems (in the country, ministry, company or territory) should not be discussed publicly because this will demean the achievements of the Revolution.

This blindness, common to both indolent and opportunist people, common also to those holding high positions or not, can strengthen the sensation that everything is all right. It’s very dangerous to confuse reality with our best wishes, and that by clinging to our society’s noble paradigms we fail to discover when, where, and how deeply reality proves them faulty. This would be the worst possible service to the Revolution.

There’s a scientific principle that says that to solve something, it is necessary first to recognize it and to elucidate it. For a long time there was strong resistance to accepting that corruption larvae had been already incubated in our society. Corruption was considered profanity, as if it could condemned us, we who have so much accumulated honesty. In the long run, here we are creating a General Controlership of the Republic.

Some perceive that healthy criticism – which, by the way, should not stop at words but continue in actions and transformations – is giving in to weakness; that it’s like giving weapons to the enemy. The truth is that the most dangerous missile we can give those who want to dismantle our 50 year work is silence. To keep silent when we see pretenses, double morals, conformity, or the disappearance of militant intransigence against wrongs that are incubated and develop before our very own eyes.

European socialism disappeared because it lost the ability to see what was really happening, and the compass to correct the route. This lesson cannot be forgotten. It is similar to Dorian Grey’s tragedy, Oscar Wilde’s character the one who was obsessed by narcissism, hid his portrait, so that he didn’t have to see the signs he was incorporating every time he made a blunder. Cuba has enough light to see herself in the mirror, and to correct her ugliness.

Laundries are reopened

Laundries are reopened

Although This Service Is Almost 60% Subsidized by the State, 32 Laundries Have Been Reopened in the Country in the Last Year and a Half.

By Haydée León Moya

August 4, 2009 00:42:10 GMT

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Cecilia González and her daughter Alioska opened their purses almost at the same time. They are standing in front of the cashier of a glistening laundry on Ayestaran Street in Havana. “It’s 77 pesos”, the employee says. And the young girl is the first one to extend her hand and pay.

Outside we heard this dialogue between the young girl and the lady:

– It’s a little bit expensive, isn’t it, “mi’ja?”

– No Mom, I think the price is right, because neither of us had to do it.

– But, will we be able to do it twice a month?

– Sure… sometimes what we don’t have is time, or detergent…

Zelmira Ramírez, laundry manager, also heard this conversation, and reached the same conclusion they did. If you don’t have to buy detergent, nor spend electricity at home, it’s worth it. If they hand in the dirty clothes, go to work and pick them up on the same day when they come back home, and pay in “pesos”, it’s really worth it, mi’jita!

Then, the experienced laundry worker, comments, “You cannot compare these machines with the clothes rippers called ‘Aurika’”.

“Well, they were also a great help”, the lady says, and leaves pleased.

The manager informs us they work from 7 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. Monday through Saturday, and on Sundays from 8:30 a.m. at 12:30 p.m. The price for washing and drying depends on weight, but ironing is charged by piece. “It’s a little more expensive, because compared to washing and drying, it consumes more electricity. We also have a very good new sewing machine in case a hem or some other stitches need sewing”, comments Zelmira.

Arnold Díaz, a 20 year-old boy who is already in love with the ironing machine he operates, says he also irons at home. He likes to do this job and he is not planning to leave. But, he thinks wages should be a bit higher so people wouldn’t leave looking for better paid jobs elsewhere.

People are thankful for the appearance of several remodeled laundries in different ‘barrios’ of the city. They have used places that already existed but hadn’t been repaired in more than 15 years.

Eduardo Tomé Consuegra, provincial director of commercial services in the capital, told JR that 15 laundries were reopened in Havana. Nine of these have been equipped with totally new and automated technology. The equipment includes five or seven washing machines, three or four dryers and an ironing machine or “planchín”. The equipment was bought in Spain at a cost of 70,000 dollars per module.

He said that in most of these restored facilities there is a payment system that stimulates workers and guarantees the service quality. He also said that the new modules will soon be found in all city units.

Tome said repairs have been made thanks to the cooperation of other provinces, especially with equipment installation, and to unit workers zeal in construction work. In this way, little by little, they have saved units that provided this type of service from dilapidation.

Mirurgia Ramírez Santana, national director of Service in the Ministry of Internal Trade, explains that 1,300,000 dollars were invested in 2008 to recover these basic services. The money was used to purchase 20 modules, which we described before, spare parts and maintenance service from a prominent Spanish laundry chain.

She reported that despite economic limitations and that the State subsidizes 60 per cent of this service, 32 laundries have been remodeled through out the country. A budget was approved to purchase 11 more modules, because the goal is that at least one new module is installed in every province before the end of the year.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

You must be logged in to post a comment.