The Drama of the Liner Saint Louis in Havana (May 1939):

A Shameful Page in the History of the United States,

and Cuba as well.

By Michel Porcheron

[Translated from the French by Larry R. Oberg.Edited by Walter Lippmann and Larry R. Oberg.]

On the ground floor of the elegant art nouveau Hotel Raquel, at 103 Amargura Street in Old Havana, there is a reproduction of an original oil painting signed by the great Cuban master Victor Manuel Garcia Valdés (1877-1969).

On the ground floor of the elegant art nouveau Hotel Raquel, at 103 Amargura Street in Old Havana, there is a reproduction of an original oil painting signed by the great Cuban master Victor Manuel Garcia Valdés (1877-1969).

Long unknown and undated, it commands one’s attention from its location between the reception area and the bar. From what diaspora did this painting emerge? Everything about the painter’s existence has long remained an enigma. It is not widely known today, for example, that the original belongs to Isaac Lif, a Dominican national. To the right of the painting a short note evokes the drama of the “Saint Louis in 1939”. *

This unusual picture forms a modest part of a dramatic mosaic of universal history. It stands alongside histories, academic treatises, historical documents and novels, a Hollywood film, a documentary of unpublished archives, the log book of the commander of the Saint-Louis and multiple sites, among other bits of knowledge that document the reprehensible attitude of the United States and their then-vassal state, Cuba.

This episode, the odyssey itself and the reasons for its tragic failure, is relatively unknown and often forgotten, even today. Not by all, of course, not by those, Jewish or not, who spoke and witnessed on behalf of those who disappeared. It is this “forgetfulness”, sustained by those who had their share of responsibility for the Jewish genocide, in this case the Allied governments by their complicit inaction.

This episode, the odyssey itself and the reasons for its tragic failure, is relatively unknown and often forgotten, even today. Not by all, of course, not by those, Jewish or not, who spoke and witnessed on behalf of those who disappeared. It is this “forgetfulness”, sustained by those who had their share of responsibility for the Jewish genocide, in this case the Allied governments by their complicit inaction.

On May 13, 1939, the Saint Louis, a German liner normally assigned to the Hamburg-Amerika line, embarked for Havana with 937 German Jewish passengers. Some came directly from the concentration camps, notably Dachau and Buchenwald.

On May 13, 1939, the Saint Louis, a German liner normally assigned to the Hamburg-Amerika line, embarked for Havana with 937 German Jewish passengers. Some came directly from the concentration camps, notably Dachau and Buchenwald.

Most of the passengers had either abandoned their personal goods or had managed to sell some in order to purchase, at $150 each, landing certificates issued by the responsible person on the spot and by others who issued visas to enter Cuba. The passengers were also required to pay an additional 230 Reichsmarks in case the boat was obliged to return.

This was, in fact, a propaganda operation organized by the Nazi regime. Its aim was to demonstrate that the Jews were free to emigrate, while knowing full well that most of the host countries would deny them entry. These travellers of a special type “had to buy return tickets at a prohibitive price, even though they were not supposed to return, as well as pay for the authorization to leave Germany …” (Louis-Philippe Dalember).

This was, in fact, a propaganda operation organized by the Nazi regime. Its aim was to demonstrate that the Jews were free to emigrate, while knowing full well that most of the host countries would deny them entry. These travellers of a special type “had to buy return tickets at a prohibitive price, even though they were not supposed to return, as well as pay for the authorization to leave Germany …” (Louis-Philippe Dalember).

About half of them were women, children, and elderly men, who were setting off with the dream of rebuilding their lives on the other side of the Atlantic, far from such Nazi persecutions as Kristallnacht (Crystal Night, November 10, 1938), (1) which had demonstrated clearly the barbaric nature of the Nazi regime.

On the ship, a certain tension reigned, because in everyone’s mind it was a journey without return, still the atmosphere was quite easy-going. In the 1930s, advertising images of the Hamburg-Amerika Line shipping company presented a luxurious vision of cruises aboard its liners.

On the ship, a certain tension reigned, because in everyone’s mind it was a journey without return, still the atmosphere was quite easy-going. In the 1930s, advertising images of the Hamburg-Amerika Line shipping company presented a luxurious vision of cruises aboard its liners.

The Saint Louis had eight bridges and could accommodate 400 passengers in first class and 500 in tourist. Of course, in reality, this “cruise” was Machiavellian: It was no more than Nazi propaganda endeavoring to prove to the entire world that Hitler’s Germany did not have a monopoly on anti-Semitism.

The journey of the Saint Louis epitomizes the cowardice of some democratic states when faced with the problem of receiving Jewish refugees on the eve of the Second World War and during the Holocaust.

In 2009, a book that –apart from its great success in sales, (translation rights were ceded in a dozen languages)– had already had a resounding influence on the sometimes violent debates it provoked.

This novel, Jan Karski, written in 1942 by the author Yannick Haenel and published in France by Gallimard, documents the abandonment of the Jews of Europe by the international community, although the real witness was Jan Karski, who was Catholic, Polish and a militant in the resistance. Taken prisoner at the beginning of the war, tortured by the Gestapo, Karski managed to escape and quickly joined the Polish resistance.

A clandestine courier for his country’s government in exile, Karski, then under 30 years of age, managed to enter the Warsaw ghetto. In order to inform them of the ongoing extermination of the Jews by the Nazis, Karski was given a secret mission to London in 1942 to meet with Winston Churchill and to Washington on July 28, 1943 to meet with Franklin D. Roosevelt.

At the meeting, as described in the 1942 novel, Roosevelt yawned, pretending to be interested to better hide his passive disinterest. Karski had been listened to without being heard. In 1944, he recounted these events in his war memoir Story of a Secret State: My Report to the World, published in the United States in 1944. Yet once again no one wanted to face the facts and it was already quite late.

“What interests me in this book,” writes Yannick Haenel, “is not the Shoah, but the Western crime, the deafness of the Allies towards extermination, an organized deafness.”

Everyone at the Hamburg-Amerika Line knew that the St. Louis passengers would not land as expected. Everyone that is, except for the passengers. The commander of the Saint Louis, whose name was Gustav Schröder (a name we need to remember), was ordered to sail at 8:00 PM by the port authorities of Hamburg.

These authorities were very likely hoping to see the Saint Louis arrive at the port of Havana along with two other ships also carrying Jews: the Flanders (with 104 passengers) flying the French flag and the Orduña flying the English flag, with 154 people aboard.

In the summer of 1939, Europe was preparing for war and Adolf Hitler’s Germany was preparing for the extermination of the Jews. The departure of the Saint Louis was “highly publicized and would greatly influence world public opinion.” (Margalit Bejarano).

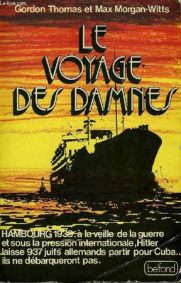

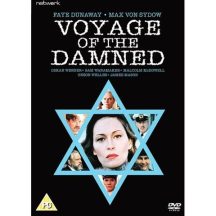

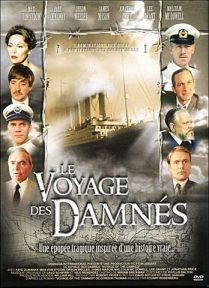

This tragic cruise would be adapted for the cinema. In 1976, Stuart Rosenberg, known for his 1967 film Cool Hand Luke, directed Voyage of the Damned (2). The script is based on the book by Max Morgan-Witts and Gordon Thomas.

In 1994, Maziar Bahari (3) directed Le Voyage du Saint-Louis (52 min.) for French television. The documentary includes testimonies from the rare survivors, those who tried to help them and members of the German crew.

In 1994, Maziar Bahari (3) directed Le Voyage du Saint-Louis (52 min.) for French television. The documentary includes testimonies from the rare survivors, those who tried to help them and members of the German crew.

The film, whose archival sequences, notably shot on the steamer during the Hamburg-Havana crossing, and unpublished still photographs, make it the documentary that best retraces this extraordinary odyssey.

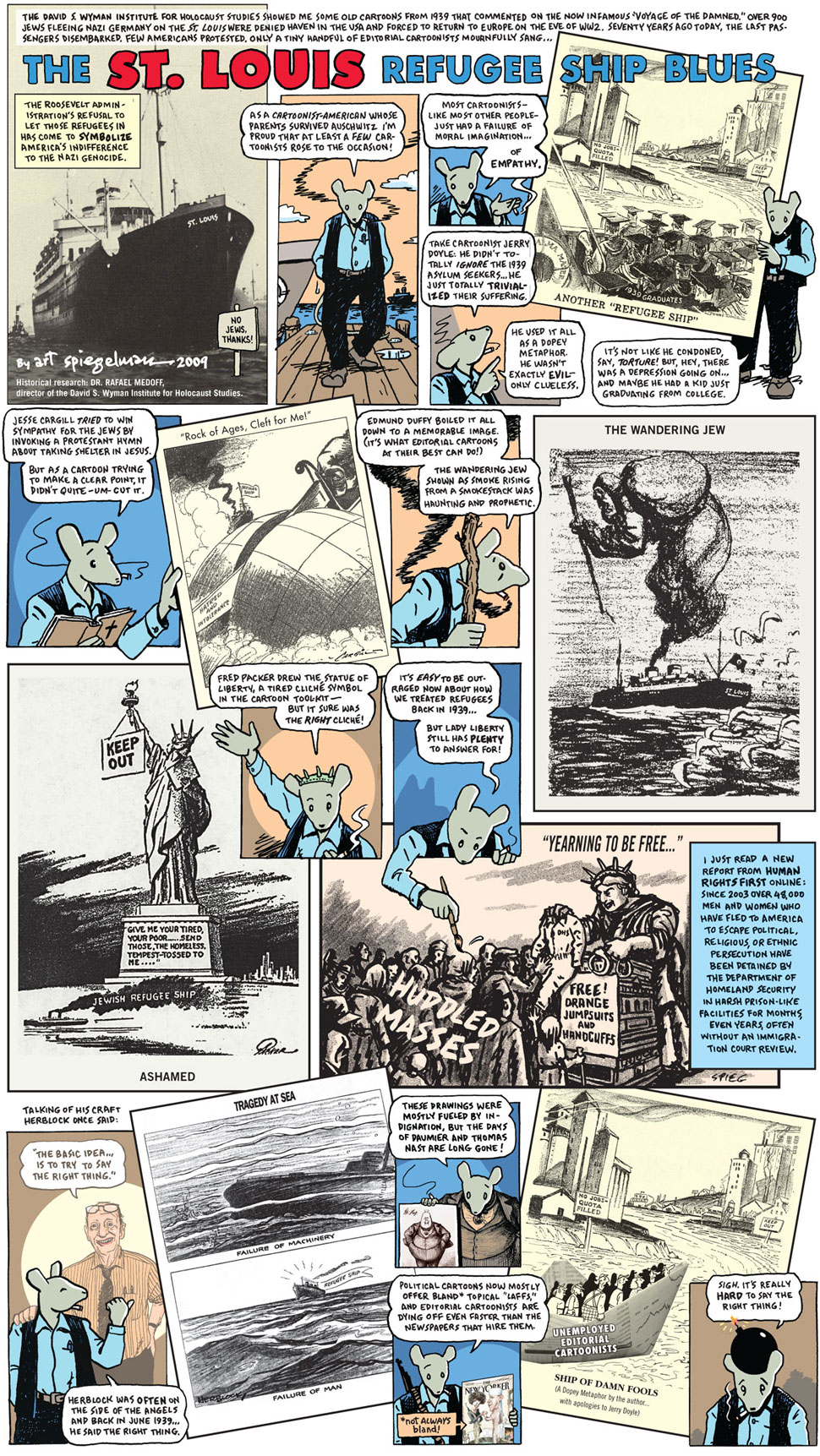

The American graphic designer, Art Spiegelman (1948), author of the famous book Maus (Pantheon Books, 1991) paid tribute in the Washington Post to the graphic designers who were among the few citizens of his country to protest the position of the American government in the Saint Louis affair. His unpublished panel from MetaMaus, a 25th anniversary Maus compendium, was published in this national daily.(4)

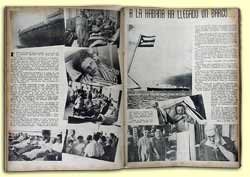

In May 1939, the Cuban Jewish community (5) awaited the arrival of the Saint Louis with great anticipation. It was an exceptional event in their lives. A German ship had never arrived carrying so many passengers. Some had family on the liner. Others knew that the refugees viewed Cuba as a first step toward arriving in the United States.

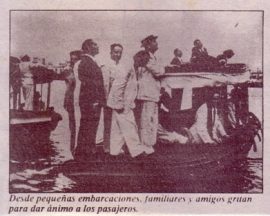

From the beginning of May 1939, the port of Havana regularly witnessed the return of Cuban fighters who had survived participation in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Various testimonies mention crossings aboard the Orduña which, it seems, made weekly crossings. A brigadista [a member of the International Brigades], from Matanzas, Julian Fernandez Garcia, reports that he “returned to Cuba, on May 27, aboard the Orduña“.

This was true as well for Juan Magraner Iglesias and Luis Rubiales Martínez, among others. Oscar Gonzalez Ancheta, had made the trip to Havana from La Rochelle, France on June 14 aboard the same boat). “We were greeted by a large crowd”, says one. “I saw loved ones waiting at the pier,” indicates another. “A large crowd came to greet us.” “

The reception was surprising. It was something that can never be forgotten. The people of Havana rushed to the Malecón where many rented small boats to greet the ship and its passengers.” (Mario Morales Mesa)

According to remarks collected by Cuban historian Alberto Bello in May 1985, Juan Magraner Iglesias recounts: “Yes, we were welcomed. The docks and the Malecon were crowded. Small boats came out to meet us. There was enormous joy. I will never forget that day.”

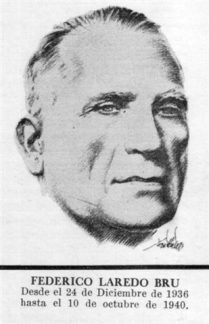

The Cuban president was a feckless Federico Laredo Bru (December 1936-October 1940). As the sixth tenant of the presidential palace since September 1933, he was unable to free the country of the effects of the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado (1925-1933). On October 10, 1940 he ceded his position to Fulgencio Batista for the latter’s first four-year term.

Cuba, while aligned with Washington’s foreign policy on the Second World War, launched in Europe in September 1939, would maintain its official position of neutrality for more than two years.

Cuba declared war on Japan, Germany and Italy on the 9th, the day after, the United States declared war against Japan (6). On the 11th, Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy declared war against the United States.

On May 23, when the Saint Louis was on its tenth day of the crossing, Captain Schröder received a telegram informing him of probable difficulties in disembarking his passengers in Havana.

Although Schröder was fully aware of what was happening in Germany, he was not pro-Nazi and he knew nothing about the Cuban events of the years 1938 and 1939. He would learn in two words that Decree 55, governing entry into Cuba … through May 5, 1939, was null and void, replaced by Decree 937, signed by President Federico Laredo Bru.

The latter had issued a decree invalidating all landing certificates. Entry to Cuba now required written authorization of the Cuban Secretaries of State and Labor and the mailing of a $500 security deposit (something not required of American tourists). On Friday, May 26, he received a second telegram (“Anchor at the anchorage, do not attempt to dock”) instructing him not to dock at the main Havana port and direct the Saint Louis towards the Triscornia administrative area.( 7).

On Saturday, May 27th, at 4:00 AM, the luxurious cruise ship Saint Louis arrived on the eastern side of Havana harbor in the Triscornia administrative area. For its passengers, hope was at its zenith.

It was not the immigration office officials who were the first to board, but rather the coastal police.

No one was allowed to disembark, apart from a few crew members. One refugee, Max Lowe, attempted suicide by slashing his veins and throwing himself overboard and was, by force of circumstance, admitted to the Calixto Garcia hospital in Havana.

For ten days, the difficulties were such that the Saint Louis –whose presence in the port had become “a real disturbance to public order”– was ordered on June 2 to leave Cuban territorial waters. Of the 937 passengers, only some 25, the only ones with proper visas upon leaving Hamburg, were allowed to land.

For ten days, the difficulties were such that the Saint Louis –whose presence in the port had become “a real disturbance to public order”– was ordered on June 2 to leave Cuban territorial waters. Of the 937 passengers, only some 25, the only ones with proper visas upon leaving Hamburg, were allowed to land.

To speed up the departure, the ship was resupplied with food, drinks and fuel. Escorted by navy patrol boats and the police, the Saint Louis moved away from the Cuban coast … Gustav Schröder took it upon himself to set the course for the United States. The boat sailed so close to Florida that passengers could see the lights of Miami. Some refugees sent a cable to President Franklin D. Roosevelt asking him to grant them asylum.

Roosevelt never responded. For three days the St Louis sailed along the coast of the United States without ever being allowed to dock. The same thing occurred in Canada where the authorities aligned themselves with U.S. and Cuban policy. In fact, they were aligning themselves with the policy of Cordell Hull, Secretary of State in the Roosevelt government: the pretext being that immigrant quotas had been filled.

“Roosevelt was clearly absent, as was the Canadian Prime Minister, Mackenzie King, who privately declared that he did not care to have too many Jews in his neighborhood” (Christophe Alix) … On June 6, short of food and only 25 days after its departure from Hamburg, the Saint Louis, with its human cargo, had no alternative but to cross the Atlantic in the other direction toward Europe. But where to? Gustav Schröder sailed the Saint Louis at low speed, as if he were waiting for a last-minute solution in the open seas.

On March 11, 1993, Captain Gustav Schröder was posthumously recognized as Righteous. Later, Jan Karski, who died in 2000, would be granted the same recognition.

The behavior of German Captain Schröder during the course of the voyage surprised the passengers from the start. Despite the presence on board of a small number of Nazi agents, including Otto Shiendick of the Gestapo, he insured that “the journey take place as if it were a normal cruise and that the refugees be treated with the utmost respect.” The 14 days of travel therefore were joyous and festive (Louis-Philippe Dalembert), with benefits well beyond those routinely offered by the liner and the expectations of the asylum seekers.

===

According to Dalembert (LPD) on May 23, Schroeder assembled a number of passengers, lawyers and others with a special knowledge of law, in an effort to resolve their difficulties. “In his soul and conscience he knew that he would do everything possible to help these people find a host country” (LPD).

In Triscornia, he would not oppose those who were observant from using a corner of the Saint Louis as an improvised synagogue. Obliged to return to Europe, Captain Schröder seriously considered scuttling his ship along the British coast, an action that would make it impossible for his passengers to be returned to Germany.

Schröder died in 1959. On March 11, 1993, he was posthumously awarded the Righteous Among the Nations medal by the state of Israel. As early as May 13, 1939, he had kept a personal logbook. Heimatlos auf hoher See (The St Louis Epoch), Berlin: Beckerdruck, 1949.

What happened in Havana between May 27 and June 2? Why were more than 900 German Jewish refugees turned away? Above all, it was because the government of Laredo Bru always obsequiously obeyed Washington’s directives. Internal events also had an obvious affect:

What happened in Havana between May 27 and June 2? Why were more than 900 German Jewish refugees turned away? Above all, it was because the government of Laredo Bru always obsequiously obeyed Washington’s directives. Internal events also had an obvious affect:

First of all, since November 8, 1933, the “Ramon Grau” law required employers to employ at least 50 percent native Cubans. The slogan of the first Presidency (Grau San Martin, September 1933 – January 1934) “Cuba para los cubanos” [Cuba for the Cubans] was not directed against the Jews as such, but against all foreign populations.

Moreover, and even more seriously, a xenophobic and anti-Semitic atmosphere had been a reality since 1933, even though it was not officially encouraged by the government (no Cuban government of the period would have had an openly anti-Semitic policy, and the vast majority of the population was not anti-Semitic.)

The first anti-Semitic public demonstrations appeared in the last months of the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado, whose colleague, German dictator Hitler, had been in power since January 30, 1933. In Germany, as early as July 1932, the Nazi party had won a majority in the Reichstag. Hermann Goering became president. Hitler’s Mein Kampf had been published in 1925. Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda ministry was fully operational from its inception in March of 1933. The first anti-Jewish measures date from July 1933, but anti-Jewish propaganda had begun even earlier.

The first anti-Semitic public demonstrations appeared in the last months of the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado, whose colleague, German dictator Hitler, had been in power since January 30, 1933. In Germany, as early as July 1932, the Nazi party had won a majority in the Reichstag. Hermann Goering became president. Hitler’s Mein Kampf had been published in 1925. Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda ministry was fully operational from its inception in March of 1933. The first anti-Jewish measures date from July 1933, but anti-Jewish propaganda had begun even earlier.

In Cuba, information about Nazi persecution of European Jews arrived regularly. National-Socialist propaganda as well. It found fertile ground among the wealthy and less wealthy Spanish traders, who viewed the arrival of new Jewish immigrants with a jaundiced eye. Some even supplied arms to Nazi “delegates” in the Cuban capital.

The mouthpiece of these members of the Spanish community was the newspaper El Diario de la Marina published by José Ignacio (Pepin) Rivero, whose family also published two other newspapers, Avance and Alerta. Anti-Jewish actions intensified at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936. The Spanish Falange in Cuba and the Nazi agents made common cause in denouncing the “Jewish danger” in the name of safeguarding the Spanish race.

In 1938, the Partido Nazi Cubano was created by a certain Juan Prohias. It had its headquarters at 406, 10th street (between 17th and 19th streets) in the central district of Vedado. Every day on his radio show, Hora Liberal Independiente, Prohias attacked the Jews and their immigration into Cuba.

He was given a personal address on Flores Street, between Enamorados and Santo Suarez. Although the authorities did not display official anti-Semitism, they never bothered the fascist or Nazi groups and did not seek to neutralize or prohibit them. El Diario de la Marina, the daily newspaper of the Francoists, had always been published without interference. It had never been banned.

Fulgencio Batista

On Cuban territory, the network of Nazi agents was composed of some 60 members. The newspapers of the Rivero group had called for a demonstration to protest against the arrival of “foreign Jews” aboard the Saint Louis.

The xenophobic and anti-Semitic atmosphere was further fueled by Primitivo Rodriguez Rodriguez, who was part of the militant wing of the Partido Auténtico, the party of former President Ramon Grau. According to Grau, the Cuban people had a duty to “fight against the Jews until the last of them had been driven out” (L.P.D).

Paradoxically, a certain Louis Clasing, Hamburg-Amerika’s director in Havana, was part of this movement as well. He immediately financed the campaign to reject the Jewish refugees who, ironically, had been transported to Cuba by his own company. Thus, this Nazi agent was responsible for demonstrating that Jews were undesirable everywhere, not only in Germany.

The Jewish community did not remain inactive, having years before successively created the Centro Intersocial Hebreo de Cuba; the Jewish Committee for Cuba; the Central Committee of the Sociedades Hebreas de Cuba; the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS); and JOINT (the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee). But these societies were more like community self-help and defense organizations than militant movements in the life of Cuban civil and political society.

Some Jews owned flourishing shops. Many were tailors, furriers and shoemakers. They were also active editorially and some were magazine publishers. A number of Jews were militants in progressive organizations.

One of them, Fabio Grobart, was one of the 13 founders of the Cuban Communist Party (August 1925), along with three other “polacos” (Polish, Poles), Gurwich, Grinberg and Wasermann. Among the Jewish refugees living in Cuba, Moisés Raigorodsky Suria was one of those who joined the Spanish Republicans between 1936 and 1939.

If the mission of the Saint Louis failed, it was partly due to the political context created by the new Decree 937. In other words, internal struggles for power. Those involved included the puppet president Laredo Bru, the Director General of the Immigration Bureau, Manuel Benitez Gonzalez; the man of the “landing permits”; and of course, the “strong man of power”, the head of the army, former sergeant Fulgencio Batista; as well as Lawrence Berenson, New York lawyer for JOINT (the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee) in the USA and Batista’s business lawyer.

If the mission of the Saint Louis failed, it was partly due to the political context created by the new Decree 937. In other words, internal struggles for power. Those involved included the puppet president Laredo Bru, the Director General of the Immigration Bureau, Manuel Benitez Gonzalez; the man of the “landing permits”; and of course, the “strong man of power”, the head of the army, former sergeant Fulgencio Batista; as well as Lawrence Berenson, New York lawyer for JOINT (the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee) in the USA and Batista’s business lawyer.

The latter did not wish to know anything and made no gesture. It was the eve of the presidential election campaign and Batista did not wish to take any risks, especially not with regard to Washington. He would succeed Laredo Bru for his first term as president. In order to get rid of Manuel Benitez, Laredo Bru opened an investigation, charging him with “repeated corruption.”(8). Thus, Benitez was going to pay for all the others, including his old friends and bosses.

For several days, in addition to attempts to negotiate between special envoy Berenson and the emissaries of Laredo Bru, the event gave evoked lively public interest. Friends and relatives, some from the United States, as well as newcomers, could approach the Saint Louis aboard small craft and communicate with passengers by signaling or shouting.

The press as a whole followed the unfolding of the affair and in town everyone shared the latest developments in the saga of the Saint Louis. Messages of solidarity with the passengers arrived from different countries, often demanding the intervention of President Roosevelt. “During the entire week, the drama surrounding the ship was the focus of public interest.” (Margalit Bejarano).

Of the 120 Austrian, Czech and German Jews who were, on May 27, 1939, aboard the Orduña, only 48 were able to land, despite the fact that their papers were not in order. With the other 72 refugees, the Orduña headed for South America.

After crossing the Panama Canal, it made brief stops in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, where only four refugees were allowed to disembark. The other 68 were transferred to another English ship which was going back toward the Panama Canal. Seven of the 68 obtained visas for Chile while in Balbao. The last 61 were interned at Fort Amador in the Canal Zone where they remained until they were admitted to the USA in 1940.

As for the 104 Jews on the Flanders, none were allowed to land. The French boat headed toward Mexico, but without success. It then headed back to France, where the French authorities placed its passengers in an internment camp.

One can imagine what followed. In Europe, 200 Jews embarked on another ship, the Orinoco, originally due to arrive in Havana in June of 1939. After the events of May, however, this trip was canceled. No one was allowed to land and all 200 ended up returning to Germany, where their fate was marked out for them.

After the outbreak of the World War, the arrival in 1942 of two other boats, the Sao Tomé, from Lisbon and Casablanca, and the Guinea, marked the temporary end of refugee immigration. Four hundred and fifty passengers had been able to land, thanks to the intervention of countries of the Allied Forces.

But they had to spend eight months in the Triscornia administrative area and were not allowed to stay on the island itself. Margalit Bejarano says that it was from the testimonies she had collected that the history of the Sao Tomé appears for the first time.

A week after the Saint Louis had left Havana, the only contacts that Gustav Schröder had were those with SEAL in Europe. Four countries had agreed to receive the liner’s refugees, France (224), Holland (181), Belgium (214) and England (287). It was on June 10th that Schröder learned by telegram that he could land in Belgium.

The Saint Louis finally reached the port of Antwerp. In September 1939, the war broke out. More than 680 refugees from France, Belgium and Holland would be among the deportees and most would perish in Auschwitz and other concentration camps. Less than a third of the passengers – those who were able to land in England – survived the Holocaust.

The Saint Louis was heavily damaged by fire that occurred during the allied bombings of Kiel on August 30, 1944. It was, nonetheless, repaired and served as a hotel boat in Hamburg from 1946 until 1952 when it was sent to Bremerhaven to be scrapped.

Gerge Blachmann in 1923

“Irony of History. Some passengers, like the Blachmanns, the Reifs and the Gottfriedes later succeeded in settling in the USA where they re-started their lives.”(LPD)

Notes:

* – The reproduction, also on canvas, is picture perfect and shares the exact dimensions of the original (Diáspora, oil on canvas, 94 x 96.8 cm). According to the testimonies of the first owner, a collector and close acquaintance of the painter, the theme of the painting, actually titled Los Olvidados [The Forgotten], could be identified and an imprecise date, the 1940s, tentatively advanced. However, as Ramon Vazquez Diaz, a specialist in Cuban art, writes: “We do not know the precise circumstances and motivations that led to this oil, which has never been taken out of private collections. Personal impulse or fulfillment of an order?” Http://www.vanguardiacubana.com/articulos/Victor-Manuel-homenaje-comunidad-hebrea.htm [image unavailable 2017]]

In the picture, the protagonists, women and children, are shown to be ashore rather than on the ship, which is contrary to the facts.

Victor Manuel Garcia (cf. p.374, Catalog of the exhibition “Cuba Art and History, from 1868 to the present day“, Museum of Fine Arts of Montreal, 2008): He presented his first personal exhibition in 1924. In 1925, he visited Europe for the first time.

On his return to Cuba in 1927, he presented a personal exhibition and participated in the Art Nouveau Exhibition, an event that marked the emergence of modern painting in Cuba. Since then, he has been considered one of the principal reformers of Cuban art, not only for his own work, but also for the influence he exerted among young artists.

In 1929, he left for Europe, traveling to Spain and Belgium and settling in France. It was in Paris that he painted La Gitana tropical [The Tropical Gypsy], a work emblematic of all his paintings. He exploited two major themes he never abandoned: the female portrait and the Cuban landscape.

His works were awarded prizes at the National Salon of Painting and Sculpture in 1935 and 1938. At the 1959 annual exhibition, in tribute to him, he was awarded a retrospective exhibit. (Roberto Cobas).

(1) – Kristallnacht [Crystal Night] (November 9-10, 1938), orchestrated by Goebbels, ended with 7,500 Jewish shops being looted, hundreds of synagogues burned and 30,000 Jews arrested. To escape these abuses, more and more Jews left Germany while there was still time.

Beginning in October 1941, all Jewish emigration would be prohibited. In Europe, Jews would find refuge mostly in Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, France and Switzerland. In the Americas, the largest number took refuge in the United States and, to a lesser extent, in Argentina. Finally, some tried their luck in China. But many would ultimately be caught up in the war.

As early as 1933, Hitler began imposing racist theories on Germany. He started by enacting a series of discriminatory measures. On April 7th non-Aryans were banned from civil service. In September 1935, the Nuremberg laws prohibited mixed marriages and deprived German Jews of their civil rights and citizenship. Violence increased over the following months.

(2) – The film, directed by Stuart Rosenberg (1928), while recounting the story, unfortunately makes use of some of Hollywood’s most melodramatic clichés. The commercialization of the film and the parade of stars playing sketchily drawn characters, discredited it. However, few films have had such a brilliant cast: Faye Dunaway, Max von Sydow, Oskar Werner, Malcolm McDowell, Orson Welles, James Mason, Lee Grant, Ben Gazzara, Katharine Ross, Luther Adler, Paul Koslo, Michael Constantine, Nehemiah Persoff, Jose Ferrer, Fernando Rey, Maria Schell, Helmut Griem, Julie Harris, Sam Wanamaker, Denholm Elliott. Although the film was a British production, it proves that Hollywood is capable of anything. Lee Grant was nominated as best supporting actress for an Oscar in 1977. The film was also rewarded with numerous other nominations.

(2) – The film, directed by Stuart Rosenberg (1928), while recounting the story, unfortunately makes use of some of Hollywood’s most melodramatic clichés. The commercialization of the film and the parade of stars playing sketchily drawn characters, discredited it. However, few films have had such a brilliant cast: Faye Dunaway, Max von Sydow, Oskar Werner, Malcolm McDowell, Orson Welles, James Mason, Lee Grant, Ben Gazzara, Katharine Ross, Luther Adler, Paul Koslo, Michael Constantine, Nehemiah Persoff, Jose Ferrer, Fernando Rey, Maria Schell, Helmut Griem, Julie Harris, Sam Wanamaker, Denholm Elliott. Although the film was a British production, it proves that Hollywood is capable of anything. Lee Grant was nominated as best supporting actress for an Oscar in 1977. The film was also rewarded with numerous other nominations.

This film, Hubert Niogret wrote in Positif, is “superficial, and ultimately dishonest despite its good intentions, since it actually obscures the historical drama behind a two-penny soap opera script.” The music of Lalo Schifrin saves nothing.

3) – Captain Schröder, who is credited as a co-writer was most probably the only person to have contributed material, in his case his logbook, to the script. In terms of casting, we find Manuel Benitez Jr (In Miami) Manuel Benítez, Laredo Bru and passengers, Philip Freund, Karl Glesman, Don Haig, CD Howe, Herbert Karliner, William Lyon Mackenzie King, Sol Messinger, Harry Rosenbach. Marx, Liesl Loeb, Jane Ripotot, Susan Schleger, Muriel Edelstein, Susan Shanks.

3) – Captain Schröder, who is credited as a co-writer was most probably the only person to have contributed material, in his case his logbook, to the script. In terms of casting, we find Manuel Benitez Jr (In Miami) Manuel Benítez, Laredo Bru and passengers, Philip Freund, Karl Glesman, Don Haig, CD Howe, Herbert Karliner, William Lyon Mackenzie King, Sol Messinger, Harry Rosenbach. Marx, Liesl Loeb, Jane Ripotot, Susan Schleger, Muriel Edelstein, Susan Shanks.

(4) – The St Louis Refugee Ship Blues by Art Spiegelman.

“Few Americans protested, only a tiny handful of editorial cartoonists mournfully sang… The St. Louis Refugee Ship Blues.“ (Art Spiegelman.) He had found these drawings in the archives of the David S.Wyman Institute for Shoah Studies. In Maus, a graphic novel (1972, published in book form from 1986 on), Art Spiegelman poignantly recounts how his father survived the Holocaust.

Few cartoons, immediately upon their publication, have been considered major cultural events. This, however, was the case with Maus, (mouse in German) an autobiography in the form of an animal cartoon. In the United States, perhaps even more so than in Europe, comic strips were considered mere entertainment. To its credit Maus made many American intellectuals aware that this mode of expression is not inherently insignificant.

(5) – In popular usage in Cuba, a Jew was often called a “Polaco” (Pole, Polish). “Just as the Spaniards here are called ‘gallegos’, all Jews, regardless of the country from which they came, were ‘polacos’. Polaco was part of the landscape.” (Ciro Bianchi, 2008).

(5) – In popular usage in Cuba, a Jew was often called a “Polaco” (Pole, Polish). “Just as the Spaniards here are called ‘gallegos’, all Jews, regardless of the country from which they came, were ‘polacos’. Polaco was part of the landscape.” (Ciro Bianchi, 2008).

The Cuban journalist and author indicates that in 1945 the Jewish community numbered some 25,000, of which, according to another source, 5,500 arrived between October 1940 and April 1943. Around 1935, some 12,000 Jews lived in Cuba. It was in the 1920s that Polish immigrants arrived in large numbers.

(6) – President Roosevelt waited for the Japanese air attack on U.S. military base at Pearl Harbor (December 1941) to enter the war. This inaction meant, implicitly and explicitly, that as early as 1933, the United States– along with Great Britain– did nothing more than try to calm the ardor of Adolf Hitler. First, Roosevelt disregarded the Nazis policy of persecution of the Jews and, from 1939 on, he ignored their systematic extermination (the Shoah). A resolution pased by the U.S. Senate in 1934 expressed “surprise and sorrow” at the situation of the Jews and demanded that their rights be restored. The State Department, however, ensured that the resolution was not widely publicized. Neither the invasion of Austria, nor the Anschluss itself, nor the annexation of the Sudetenland, nor the aggression against Poland, made the Washington authorities react. On the issue of European Jews, it is clear that Roosevelt’s United States might have acted otherwise. Henry Feingold in Politics of Rescue: The Roosevelt Administration and the Holocaust, 1938-1945 (1970) demonstrates that “Roosevelt did not take steps that could have saved thousands of lives. For him, it was not a priority. He left the matter in the hands of the State Department, where anti-Semitism and an inflexible bureaucracy were obstacles to action.” (Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States: 1492 to the present.)

For the writer Yannick Haenel, the Évian conference of 1938, intended to encourage the reception of Jews by the Western powers, “resulted in an obscene capping of all immigration quotas”. He adds: “After all there is nothing but hypocrisy, calculation, and foreign ministry rhetoric” (French daily Libération, October 22, 2009).

It should also be pointed out that at no time during the Nuremberg trial did the United States raise the question of Western responsibility. “It was from these crimes,” says Haenel in Liberation, “that the so-called free world was born. We are heirs to this constellation of lies and fundamental indecency that rotted the foundations of Europe from its very beginnings in 1945.”

In the United States, the anti-Semites, who were quite numerous, had more than enough to read. In addition to Henri Ford (yes, the famous automaker of the same name), a “rabid racist” according to Timothy W. Ryback; Madison Grant, author of End of the Great Race (1916) (Ryback, 2009). Ryback: “Grant’s book, one of the most destructive of the twentieth century, explains that Europe and the United States would be annihilated because of immigrants.” Thus when 900 Jewish refugees approached the coast …

(7) – In the Havana harbor town of Casablanca, on the other side of the city, there was a place called Triscornia that, until 1959, was used as an immigration or internment camp, something that today would be called an administrative detention center. For those arriving through the capital’s regular port, Trisconia was an unknown approach. All possible controls, depending on the period, had been practiced. Some authors trace the history of Triscornia back to the final years of slavery. In each foreign colony in the country, stories circulated about the detention, more or less long, of one or more of their relatives or friends. The travellers who were detained were required to name the person who had “invited” them, give the address where they intended to stay, report their means of subsistence, etc. Medical checks were regularly carried out. Several barracks containing dormitories had been built and, according to witnesses who lived there, an administrative center and a field hospital as well. Triscornia also offered a means of refusing one or more foreigners judged, for whatever reason, to be undesirable. This was, of course, the case with the German Jewish refugees from the Saint Louis.They were required to remain on board the ship, without being admitted to the camp. The first explicit mention of Triscornia, made by Cuban historian Margalit Bejarano, concerns Jewish refugees in the 1920s. In 1942, a German refugee, Emma Kann, spent more than six months there before being authorized to live in the Cuban capital. This was also the case for another refugee, Lotte Burg, also German.

(8) Benitez was accused of selling landing permits to travellers who were not tourists, but rather political refugees. Worse, he had no sense of fairness and kept the profits ffrom his (now) illicit traffic for himself. The licenses, signed by Benitez in person, were sold to candidates for entry to Cuba. According to Margalit Bejarano, “the permits were not legal documents, but their sale was compatible with the current political norms of the country“. They were presumed to allow a temporary stay in Cuba, but under two conditions: immigrants could not work and were required to guarantee that they possessed sufficient resources to meet all of their needs. Under these circumstances, HIAS and the JOINT could not intervene, hence the importance taken by the “majers” (according to the Hebrew vocabulary), in other words the “arregladores” [fixers] or private intermediaries who “arranged” administrative problems. “The Benitez licenses that accompanied each of the tickets sold by the Hamburg-Amerika Line were transformed into a true business of human trafficking, which though illegal, was not secret.” (Margalit Bejarano)

The Benitez system, with a relatively small number of “customers,” had been set up in 1938, upon the arrival of mainly Austrian Jewish refugees (the annexation of Austria occurred in March of 1938). It was not until January 1939 that his business began to flourish. Each Hamburg-Amerika Line (Actually, HAPAG) ship carried about 600 refugees from Germany, Austria or Czechoslovakia. Thus, he would have amassed a personal fortune of some $500,000 to one million dollars. Benitez’ son, Manuel Benitez Valdés, an officer from the Pinar del Rio area, was also involved in the business. According to Laura Margolis, director of JOINT in Havana, most of the “majers” were in Berlin itself. Having taken refuge in Miami, where he was responsible for an anti-Castro radio station, Manuel Benitez’s son acknowledged that his father flaunted immigration laws for personal gain, but explained that “it saved lives”!

Sources Consulted:

In French:

– Maziar Bahari, Le voyage du Saint-Louis, a 1994 French television documentary.

– “The unlawful disembarkation of the wandering Jews of the Saint Louis,” chapter 17 of the Le Roman de Cuba, by Louis-Philippe Dalembert (Ed. du Rocher, 2009, 271 pages). Dalembert, author of a doctoral thesis on the Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier, was awarded the 2008 Casa de las Américas prize, the most important Cuban literary prize, for his novel Les dieux voyagent la nuit, Ed. du Rocher, 2006).

In Spanish:

– “La Comunidad Hebrea de Cuba, la Memoria y la Historia,” authoritatively compiladora: Margalit Bejarano, Ed. Instituto Abraham Harman, Universidad Hebrea de Jerusalén, 1996, 276 p.

– “La historia del buque San Luis: Perspectiva cubana,” M. Bejarano, Universidad Hebrea de Jerusalén, 1999, 32 p.

Hella Roubisek

– Juventud Rebelde: May 5, 1996, by Ignacio Hernández Rotger, a testimony taken in Cuba from a refugee from the ship, Hella Roubisek, 13, who was accompanied by her mother. Her father, Without a job, lived in Havana where he had landed some time before. Three photos are taken from the book “El viaje de los malditos“.

- Sarusky, Jaime (1931). Las Dos caras del paraíso, Ed. Unión, La Habana, 2006. (It is curious that Sarusky mentions the date of” June 1937″). From the same author: in Revolución y Culturan° 3, July-September, 2001, pp.46-49, “Hebreos en Cuba”

- “Judios”, by Ciro Bianchi Ross, in “Yo tengo la historia“, Ed. Unión, 2008 (pages 270-274, without date, unpublished). This version reproduces Sarusky’s dating error, something he later corrected in his blog (in Spanish) http://wwwcirobianchi.blogia.com/2009/033003-los-peregrinos-del-san-luis.php

Additional reading, in English

Recommended by Walter Lippmann.

- Ruth Behar (2007) An Island Called Home; Returning to Jewish Cuba

- Maritza Corrales (2005) Jews in Cuba: The Chosen Island

- Jay Levinson (2006) The Jewish Community of Cuba; The Golden Age, 1906-1958

- Robert M Levine (1993) Tropical Diaspora; The Jewish Experience in Cuba

- Felicia Rosshandler (1984) Passing Through Havana

About the Author

Michel Porcheron is an author associated with Tlaxcala, the Translators Network for Linguistic Diversity. You are free to reproduce this translation, provided its integrity is respected and the author and the source are mentioned.

Original article published on February 2, 2010.

You must be logged in to post a comment.