St. Louis 2

There Will Not be Another Saint Louis

There Will Not be Another Shame for Cuba like the St. Louis

By Jorge Gómez Barata

March 18, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

The news moved the ink: “Cuba authorized the docking of a cruise ship British with coronavirus…” According to Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez: “At the request of the British government, the Cuban authorities granted docking permission to the MS Braemar cruise ship, with some COVID-19 infected travelers on board. According to the minister: “This is a health emergency…

The news moved the ink: “Cuba authorized the docking of a cruise ship British with coronavirus…” According to Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez: “At the request of the British government, the Cuban authorities granted docking permission to the MS Braemar cruise ship, with some COVID-19 infected travelers on board. According to the minister: “This is a health emergency…

It later transpired that today, Tuesday the 17th, upon the ship’s arrival in the port of Mariel, a calibrated operation will be triggered as a watches to disembark all travelers, evaluate and offer medical care to the sick and airlift them to Gran Brittany.

It all started on Sunday, March 8th, when the cruise ship docked at the port of Cartagena, Colombia where, along with other passengers, an American woman landed. When examined at a center city doctor, she tested positive for the coronavirus.

Unaware of the situation, the cruise ship MS Braemar, set sail for Willemstad in Curaçao and Bridgetown in Barbados, where they were denied the entry. On Wednesday the 11th, the ship’s owner’s firm was notified of the passenger’s situation and immediately issued a statement in which he reported five other cases on board. The same day, the cruise captain asked the harbor master of Cartagena permission to return which was denied, which also happened with the Bahamas.

According to CNN, on Sunday afternoon, 15 British officials made intense and unsuccessful diplomatic efforts to find a country willing and with appropriate infrastructure to receive the ship in which 1,513 people are traveling. In addition to the British, among the passengers, there are Canadians, Australians, Belgians, Colombians, Irish, Italians, Japanese, Dutch, New Zealanders, Norwegians and Swedes.

On the ship, which at the time of the order was anchored 25 miles in the Bahamas, there are four passengers and one crew member positive for COVID-19. Other people, including a doctor, are subject to quarantine after presenting symptoms. In this case, it is for practical reasons because the cruise is about 4,000 miles from England where it would take several days to arrive and about 500 from Havana, so in about a day and a half of navigation the sick passengers will be under Cuban medical coverage and soon after, those who are re-marked, they will arrive in their country.

Although devoid of the dramatic and petty nuances, the situation of the cruise ship MS Braemar has reminded me of the tragedy experienced by the passengers of another ship, the St. Louis, which, in 1939, instead of to be welcomed in Havana, was rejected, so they ended up in the concentration camps and crematoria of Nazi Germany.

During World War II, in the face of persecution in Germany, there was an exodus of Jews to the United States. At that time there was a quota system for migrants that was not extended. In that context, there was an arrangement, according to which they would travel to a nearby country and wait there to be allowed to enter North America.

Under that understanding, in Hamburg, 937 passengers boarded the Saint Louis, which on May13, 1939 set sail for Cuba. All had permits to land in Havana with refugee status. On the 23rd of the same month, in the Cuban capital the captain received the news that the permits sold by a corrupt immigration director, were overruled by the president Federico Laredo Brú. Bru agreed to issue others at a cost of $500 dollars per person, an amount that only 29 passengers could pay.

In view of the refusal of the United States and Canada to take in the unhappy travelers, scarce water, food and fuel and with the crew virtually mutinous, the ship’s captain decided to return to Europe. In the port of Antwerp, Belgium, exhausted and terrified, the unfortunates of the St. Louis who lived the illusion of being welcomed into Havana.

According to reports, the British cruise ship will dock in the port of Mariel where directly, without any contact with the Cuban population, and, under strict medical and epidemiological supervision, will board buses to Terminal Five of the capital airport, which was destined and prepared for special operations, in which they will be taken by two planes chartered by Great Britain.

On social networks, in Cuba and elsewhere, both people who are bad intentioned as well compatriots acting in good faith, expressed critical opinions. It’s their right, but in this case, more than rights, it is the duty to assist others at risk, following rules that preserve the safety of the minimum number of people involved. COVID-19 shouldn’t make us any worse. See you there.

Cuba Rejected Jewish Refugees in 1939

SS Saint Louis:

Under U.S. Pressure, Cuba Turned its Back on 909 Jewish Refugees in 1939

This is the heartbreaking story of the passengers of the SS Saint Louis liner, who in order to escape persecution by the Nazis, decided to travel to Havana, and then to the United States, but upon arrival at the Cuban port, under pressure from the U.S. government, were denied

—————————————————————————————————

Author: Dolphin Xiqués Cutiño | archivo@granma.cu

March 17, 2020 13:03:41

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

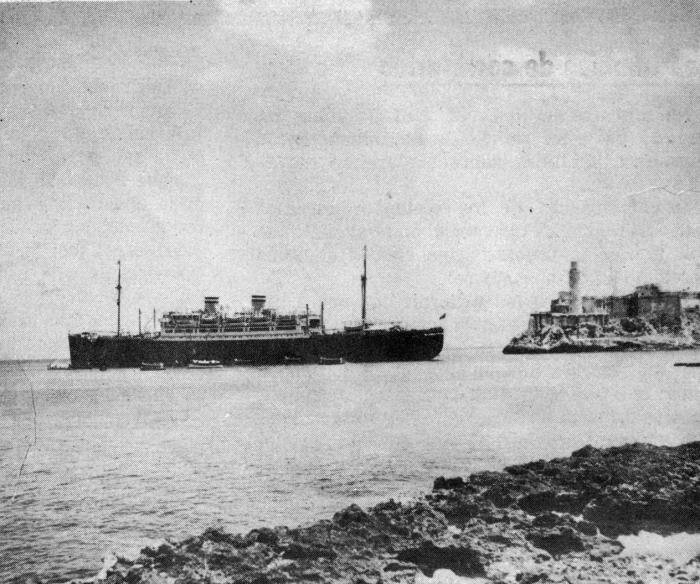

The SS Saint Louis leaving the port of Havana on June 2, 1939, when the Jewish refugees were denied landing. Photo: Carteles Magazine

This is the heartbreaking story of the 937 passengers of the SS Saint Louis liner, who in order to escape the persecution by the Nazis, decided to travel to Havana, and then to the United States, but upon arrival at the Cuban port, under pressure from the Yankee government, were denied disembarkation.

Most of the passengers were Jewish families who, with the arrival of the Nazi party to power, began to be harassed: Their synagogues and properties were burned, they were constantly harassed and, moreover, they risked being detained only because they were Jews.

937 Jews fleeing the Nazi repression were shipped to the port of Hamburg. Photo: Taken from the Internet

Also traveling were four Spaniards and two Cubans who were not Jews. Almost all of them carried their visas in order issued by the Cuban Embassy in Berlin at a cost of $200 or $300 each, a fortune at that time.

The passengers of the SS Saint Louis were traveling with the illusion of reaching Cuba and then the United States, but that did not happen. Photo: Taken from the Internet

The SS Saint Louis set sail from the port of Hamburg on May 13, 1939. Gisela Felman was 15 years old when she embarked on that unknown adventure and “she remembers her father begging her mother to wait for him but she was tenacious and always replied: I have to take the girls away for safety.”

The families enjoyed the trip without suspecting that they would be rejected in Cuba, in the United States and in other Latin American countries. Photo: Taken from the Internet

“So, armed with visas for Cuba acquired in Berlin, 10 German marks in their bag and another 200 hidden in their underwear, they headed for Hamburg and the St Louis.

The voyage took place with the usual normality of passenger ships. Games, dances, dinners, walks on deck and that its captain Gustav Schroder kept so that women, men and children could enjoy the comforts on board, knowing that those families had suffered enough on German land.

The Havanese were very supportive of Jewish immigrants. Photo: Taken from the Internet

Everything was ready for the passengers to disembark. But big was the surprise when the authorities showed up on board the ship and informed the captain that nobody could go ashore.

The Jewish immigrants were unaware that eight days before the departure of the ship from Hamburg, the then president of Cuba, Federico Laredo Bru, under pressure from the Yankees, had denied the landing permits by means of a decree. Now, in order to enter Cuba, it was required to have an authorization from the Secretary of State and another from the Secretary of Labor and to pay a $500 bonus, except for the tourists.

The SS Saint Louis in the port of Antwerp, Belgium, after sailing for almost a month through Latin America without getting any country to accept its passengers. Photo: Taken from the Internet

Of course, the Jewish refugees could not comply with the new entry regulations because they had left Germany with what little value they had left. And now they had nothing of value with them, only their lives.

Only 28 passengers were able to disembark without problems, including the four Spaniards and the two Cubans.

The SS St. Louis remained in the Havana watershed for almost a week while the lives of the 909 Jewish refugees were traded as if they were just another commodity. They were fleeing from Nazism and were caught by capitalism.

On June 2, President Laredo Bru ordered Captain Gustav Schroder to leave the port of Havana. As the ship was leaving, thousands of Havana residents came to see them off, offering their solidarity and thus showing that the Cuban people were with them.

The ship set sail escorted by two Navy boats and set course for Florida, but there they refused to receive them as they did in Puerto Rico. The captain then telegraphed the authorities in Canada, Honduras, Venezuela, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, Paraguay, and Argentina, among other countries, to persuade them to take in the Jewish immigrants, but they all refused entry.

Almost a month after his departure from Germany, the SS Saint Louis had to set out for Europe and after long conversations some Jews were accepted by Great Britain, Holland and France, confining them in internment camps. The remaining passengers disembarked on June 17, 1939, in Antwerp, Belgium.

The epilogue to this heartbreaking story goes back to the German invasion of western Europe in May 1940: approximately 670 SS Saint Louis refugees were caught by the Nazis and died in concentration camps. Some 240 survived years of starvation, abuse, and forced labor.

Sources:

Cartel Magazine, June 11, 1939

Juventud Rebelde, March 29, 2009

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | |||||

You must be logged in to post a comment.