Health 6

Obesity, a pandemic in the world

Obesity, a pandemic affecting more than 1 billion people in the world

According to the results of the National Health Survey Cuba 2020, 20% of the total population under 15 years of age is overweight, although by region, a lower proportion is apparently observed in rural areas.

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Obesity is no longer just a problem of developed nations. Photo: Reuters

Obesity, with accelerated growth in the last decades, has come to be considered the pandemic of the 21st century.

According to the website of the Cuban Ministry of Public Health (Minsap), this condition has tripled its figures since 1975.

The United Nations (UN) warned this Friday, on World Obesity Day against this disease, that in the year 2025 some 167 million people will be in poorer health due to overweight or obesity, which affects more than 1 billion people.

According to a press release from the organization, this disease affects 650 million adults, 340 million adolescents, and 39 million children.

On the other hand, it is estimated that at least three out of every ten children and adolescents, between five and 19 years of age, live with overweight in Latin America and the Caribbean, adds Minsap.

In 2020, UNICEF, the WHO and the World Bank estimated that 7.5% of children under five years of age in the region were overweight, which represents nearly 4 million children. This figure exceeds the world average percentage, which is 5.7%, emphasized the Cuban Ministry’s publication.

The COVID-19 pandemic intensified the problem with limited access to healthy food and lower purchasing power.

In Cuba, malnutrition and being underweight are not a health problem in the child population. However, overweight and obesity have been on the rise, according to isolated studies in children, as well as in adolescents and adults, according to Minsap.

These results demonstrated their association with the increase of different chronic non-communicable diseases such as arterial hypertension, ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus and certain types of cancer, among others.

According to the results of the National Health Survey Cuba 2020, 20% of the total population under 15 years of age is overweight, although by region, a lower proportion is apparently observed in rural areas. A similar behavior appears in the levels of obesity found, with a total prevalence of almost 20 %.

However, there is a trend towards greater overweight in adolescence, which could be explained by the pubertal changes that are beginning to occur. The higher figures of obesity in the youngest children constitute a warning of possible complications.

Minsap adds that in general, with respect to data from other studies carried out in our country, overweight and obesity have increased in the child population.

The negative effects caused by the increase in obesity worldwide are exported from one country to another, even reducing their economic productivity. Therefore, it is necessary to develop intervention policies that work to reverse this pandemic, the publication emphasizes.

Mujica backs Cuban doctors for Nobel

Pepe Mujica: “It is an honor to support the candidacy for the Nobel Peace Prize for Cuban doctors”.

By Maribel Acosta Damas. Cuban journalist, specialized in Television. She is a professor at the Faculty of Journalism of the University of Havana and holds a PhD in Communication Sciences.

By Maribel Acosta Damas. Cuban journalist, specialized in Television. She is a professor at the Faculty of Journalism of the University of Havana and holds a PhD in Communication Sciences.

March 12, 2021

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Pepe Mujica, Minister of Livestock and Agriculture in the first government of Tabaré Vázquez in 2005 and then President of Uruguay between 2010 and 2015. Photo: Resumen Latinoamericano.

Photo taken from Cubaenresumen.org

In my living room I have a picture of Che, and I have his letters in my memoirs, in a notebook. It turned out that Evo Morales wanted to make a faithful reproduction of Che’s wallet in the Bolivian guerrilla, the last one he had. Evo Morales had it made as a gift to his friends, and I have it. Inside there is also the facsimile copy of the campaign diary and a notebook… I keep it hanging… and I always show it to them when they come to visit. Che is still there. For us, it is an indelible attitude, no matter how much time goes by…

José “Pepe” Mujica and Lucía Topolansky at the Uruguayan ambassador’s residence in Havana, January 25, 2015. Photo: William Silveira Mora

We receive all this when we are born. So we have to try to leave something behind for those who will come after us. The world will not improve if there are no people who are concerned about its improvement. The world improves because of the work of people who make an effort.

Pepe Mujica gives an interview to Randy Alonso Falcón for the Round Table, Havana, January 25, 2016. Photo: William Silveira Mora

Now there is the internet, there is the university, so it is as if the old people are superfluous, they are left over… It is a world that only wants young people, absolutely young, and then the old men and women disguise themselves to look younger. They all want to be young and they revoke themselves: they dye their hair, they remove wrinkles, they bother with fatness… in short…

Old people are on the way to being discarded. However, sometimes old people see farther because they have lived longer and if they are not yet crippled they have the function of trying to tell things to younger people that probably they are not going to understand them at that moment, but one day they will realize that they did not see part of reality… In Asian villages there is a great reverence for old people, but in Western villages there is no reverence. That is why it is good to retire…

The former Uruguayan president is known for his modest lifestyle and direct speech. Photo: EFE

Vaccination against selfishness and inequality

Vaccination against selfishness and inequality

By: Randy Alonso Falcón

January 27, 2021

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

“It will not be an exhausted and outdated world order that can save humanity and create the indispensable natural conditions for a dignified and decent life on the planet. (…) This is not an ideological question; it is already a question of life or death for the human species.”

“It will not be an exhausted and outdated world order that can save humanity and create the indispensable natural conditions for a dignified and decent life on the planet. (…) This is not an ideological question; it is already a question of life or death for the human species.”

Fidel Castro Ruz

Speech at the Open Tribune of the Revolution, held in San José de las Lajas

January 27, 2001

Solidarity and Justice are still words in disuse even when the catastrophe concerns us all, like a great universal Titanic. A tiny and sticky virus has moved fears, shaken societies and health systems, provoked countless reflections on today and the future, but it has not succeeded in making equity and love for others prosper.

This week will mark the 100 millionth person infected with COVID-19 in the world and already more than 2 million people have died.

“Every day the gap between the haves and have-nots grows. The pandemic has reminded us that health and economics are linked and that we are all in the same boat. The pandemic will not end until it ends everywhere,” said World Health Organization Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus on Monday.

The numbers bear incontrovertible witness to the expert’s assessment.

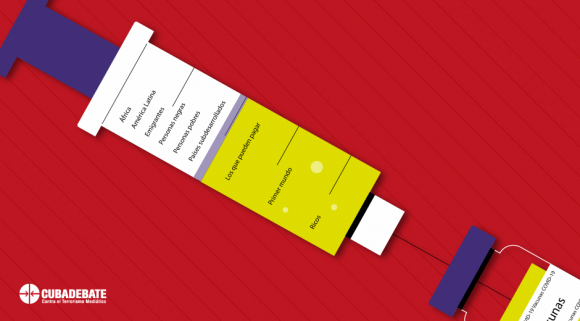

The privileged cure

Despite numerous calls from the UN and various world leaders to seek a global response to the pandemic and to facilitate and share access to a cure for the disease, narrow views and deaf ears predominate.

“Science is succeeding, but solidarity is failing,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres noted on January 15. Several vaccines are already available worldwide to tackle the SARS-CoV-2 virus, but access to them is as deeply unequal as the world we inhabit.

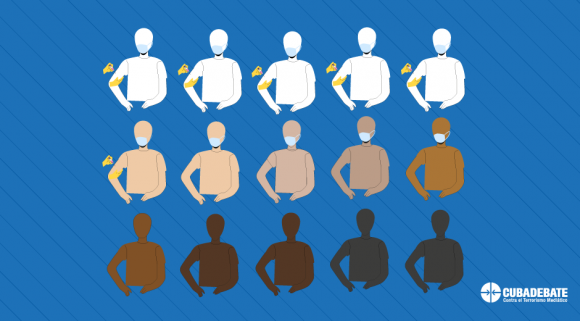

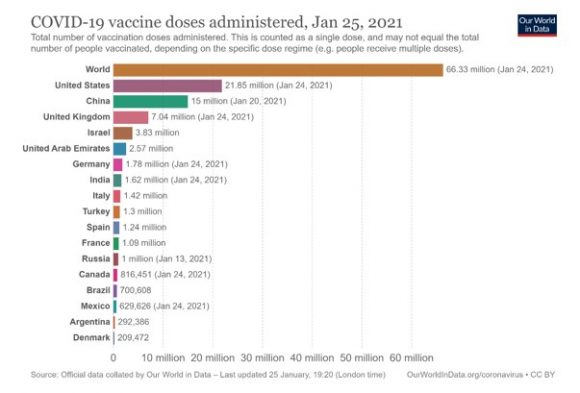

Some 66.33 million doses have been administered to date, 93% of which were delivered in just 15 countries: the US, China, UK, Israel, United Arab Emirates, Germany, India, Italy, Turkey, Spain, France and Russia, according to the data analysis platform Our World in Data, based on figures from Oxford University.

In all of sub-Saharan Africa, only 25 doses of vaccine could be administered in Guinea. Populous countries like Nigeria, with 200 million inhabitants, are waiting for the first dose.

The same scramble that took place at the beginning of the pandemic with lung ventilators, masks and protective suits is now being staged with vaccines: hoarding, overpricing and speculation. “An immoral race to the bottom,” as the WHO’s top executive described it.

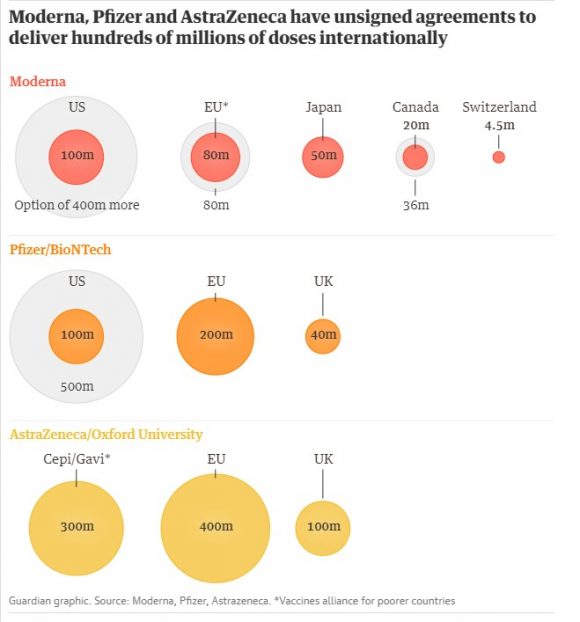

The COVAX fund, created as a sort of global effort to make vaccines accessible to the poorest nations or those with limited resources, announced that in February it will begin to deliver the first doses (they first said that in January), but it recognizes that it has been limited by the lucrative agreements of various individual nations with the pharmaceutical companies that produce the anti-COVID vaccines.

Another handicap has been the high cost of the vaccines that have the most international approval so far. As Norwegian expert John-Arne Rottingen told The Guardian, “The difficulty is that we really only have widespread international approval for marketing two vaccines: the two mRNA vaccines. The challenge is that one, the Moderna vaccine is very expensive, and the other, the Pfizer / BioNTech vaccine, which was first available and is now being applied in Europe, is moderately expensive compared to others, and requires a super cold chain. The price and cold chain makes it not the ideal vaccines for a global vaccine.”

While nations like India and South Africa are calling on the WHO to campaign for pharmaceutical companies to relinquish intellectual property rights to COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. That would allow other qualified manufacturers in the South to expand production of those antidotes; countries like the US, UK and Canada have opposed the initiative. Those three wealthy nations have purchased or reserved enough doses to inoculate their populations at least four times.

High-income countries account for 16% of the world’s population, but hold more than 60% of the vaccines purchased so far.

Rich countries account for the lion’s share of vaccine production. Graphic: The Guardian

Some forecasts put the total population of middle-income and poor countries that could be vaccinated this year at 27%. Duke University’s Center for Global Health Innovation estimates that there will not be enough vaccines to immunize the world’s population until at least 2023.

“The world is on the brink of a catastrophic moral failure, and the price of this failure will be paid in lives and livelihoods in the world’s poorest countries,” Dr. Tedros regretfully sentenced.

The virus of inequality

“Vaccine nationalism” is the exact reflection of an unequal and unjust world in which a few remain the great beneficiaries of wealth, for which billions must make do with the leftovers.

It is the “inequality virus” that OXFAM denounces in its most recent report, in which it evidences that the current failed economic system “allows a super-rich elite to continue to accumulate wealth in the midst of the greatest economic crisis since the Great Depression, while billions of people face great hardship to get by.”

While billionaires saw their fortunes increase between March and December 2020 by a total volume of $3.9 trillion-to amass an unimaginable $11.95 trillion-the poorest people on the planet will need “more than a decade to recover from the economic impacts of the crisis” accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Racial differences have also deepened. In the United States, the most powerful nation on the planet, if mortality rates were equal to those of the white population, nearly 22,000 Latinos and blacks would not have died from the coronavirus outbreak. In Brazil, people of African descent are 40% more likely to die from COVID than whites.

One of the conclusions of the Oxfam report is that “the pandemic is likely to increase inequality in a way never seen before”. The World Bank has warned that, in the current context, more than 100 million people could reach extreme poverty.

The 10 richest men in the world saw their net worth increase by $540 billion in the pandemic 2020 period. That list is topped by Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk. It also includes luxury group LVMH CEO Bernard Arnault, Bill Gates and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. According to Oxfam, the money hoarded by these potentates would be enough to prevent people from falling into poverty due to the effects of the virus and would also guarantee a vaccine for everyone on the planet.

Sunshine of the moral world

Among so much inequity and indifference, a small archipelago in the Caribbean, called Cuba, has been able to send thousands of doctors and nurses, in some 50 brigades of the “Henry Reeve” Internationalist Contingent, to more than thirty countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, Europe, Africa and the Middle East, to collaborate in the fight against the deadly disease.

Thousands of lives saved or recovered in a scenario of total complexity are the fruit of their solidarity work. The human and professional quality of these sons and daughters of the Cuban people overcomes the most diverse obstacles. It leaves a mark of affection, gratitude and example that is recognized by all those with whom they have shared and whom they have cared for.

That same country, with scarce economic resources but abundant in trained and educated talent, has been able to build an advanced biopharmaceutical industry, which is now preparing to produce 100 million doses of Soberana 02, one of the 4 vaccines on which its scientists are working. This would make it possible to immunize the entire Cuban population (it would be one of the first countries to achieve this) and to have more than 70 million doses available for other peoples of the South. There are already countries interested in acquiring it, such as Vietnam, Iran and Venezuela, Pakistan and India, the Director General of the Finlay Vaccine Institute recently announced.

Researchers from that institution are working with countries such as Italy and Canada to test the impact of the Soberana 01 vaccine on people who have already had COVID-19 and are convalescing, but are at risk of reinfection.

“We are not a multinational where (financial) return is the number one reason. We work the other way around, creating more health and return is a consequence, it is never going to be the priority,” Dr. Vicente Vérez, leader of the main vaccine research center in Cuba, explained to the press last week.

“Our world can only beat this virus one way: united,” the UN Secretary-General recently emphasized. Unfortunately, the vaccines of solidarity and justice have not been able to be applied in the rich world that dominates.

The Voice of Wisdom in Public Gatherings

The Voice of Wisdom in Public Gatherings

The usefulness and relevance of public meetings informing the population about details of the COVID-19 in Cuba are evident

By Haydee León Moya

March 20, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Guantánamo: Where they take their delegate to account, that is where it took place: in the community park. People arrived well before the scheduled time to attend a public health hearing on the coronavirus.

They were heard talking about the subject and what they were interested in being informed about. A young doctor from outside the neighborhood also arrived early and wrote down what he heard.

I never saw such quietness in the girl who was accompanying the adults. “This is very serious and you can’t interrupt,” a grandmother told her grandson, shortly before the young and very active leader of the neighborhood introduced the visitor in the white coat for a masterful lecture.

As a specialist in General Integral Medicine at the community polyclinic, he updated us on the positive cases of Covid-19 confirmed in Cuba until that evening. He explained the history of the disease, the ways in which it is transmitted, the symptoms that, if they appear, should make us go immediately to a medical institution.

He also gave the telephone number of the Command Post where one can ask for any guidance and made it clear that nobody can trust that their cough or fever is from a cold of days ago: You have to go to the doctor and demand that behavior in every house, as well as smearing hypochlorite on the common surfaces, which in the neighborhood pharmacy are regulating its sale so that everyone has enough.

“The doctor’s office is the closest, so you don’t waste any time, but you can go to the one you want,” the doctor replied.

“Listen, I know of a person who came from outside and spent the night coughing. What can you do if you don’t want to go to the hospital?” asked another neighbour.

“Well, you must isolate him and demand that he go to the doctor, or you can call the telephone I gave you and report it,” explained the specialist very seriously.

“But look, doctor: look at all the positive cases in Cuba, if not foreigners, at least they have had contact with those people or visited countries where the disease is spreading. If you see one of those cases, to prevent them from walking in the street it’s better to call the command post and have them pick you up in an ambulance, don’t you think?”, said another.

“That’s very good and it’s already planned. People who have an illness related to the characteristics of this disease should participate actively and responsibly in the protection of the rest of the population,” insisted the doctor, and answered other questions from the same court.

That is precisely the value of these public exchanges in the open air: People inform themselves, participate, anticipate and learn, thinking about their own and others with a more responsible tone.

Cuban CP on Kissing and Covid-19

Prudence

This is a struggle in which we are all involved, of a social nature, and in which each one must impose on him/herself the condition of being responsible, for his own good and that of others.

By Ventura de Jesús

March 21, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Photo: Taken from the Internet

Covid-19 continues to spread around the world, with increasing levels of infection and death. The signal is very clear: protocols for prevention and control must be followed, and very strict health rules must be observed in order to avoid at all costs contagion and the spread of the disease.

There are various measures and lessons to flatten the epidemic’s curve and the emphasis is on collective awareness, discipline, and individual responsibility.

In addition to strengthening hygiene care, experts warn that personal behavior is key. They recommend social distancing measures, such as voluntary quarantine and isolation, as well as avoiding displacement and crowding.

Others are aimed at not shaking hands and avoiding kisses, and trying to keep at least one meter away from other people, something whose benefit nobody doubts, but which to a certain extent is tormenting for Cubans, since they quarrel with habits that are deeply rooted in our society.

Visual and physical contact in Cuba does not have the same connotation as in other parts of the world. According to scholars, it is part of nature and responds to socio-cultural and historical phenomena.

Fortunately, there are those who have given up on the fraternal embraces, friendly romps and other approaches that usually characterize the encounters between acquaintances, friends and family on the island.

There are more and more people who greet you from a distance or give you an affective glance from afar. There are even those, the few, who pass by without looking. They believe that this does not hurt anyone’s feelings, and is healthy for the purpose of evading the Covid-19.

The truth is that putting aside, or postponing for the time being, the relationship of joyful camaraderie in the form of handshakes or necking, need not sour anyone’s character or be a source of laughter or mockery. Everyone should understand the reasons and not overlook the importance of caution, even against their will.

Despite many exhortations, many people still do not take this particular matter seriously, and there is no human power capable of persuading them that, for example, affectionate greetings should be avoided.

Perhaps that is why we Latinos, and particularly Cubans, are like that. There are those who think that a kiss does not hurt anyone and find it extravagant to greet each other with an elbow or with simple gestures from a distance. They consider it a useless torture and continue to obey that ancient custom of shaking hands or hugging a friend.

Although some do not seem to be aware of it, this pandemic is dangerous and causes countless setbacks, including some that are related to our daily habits.

Cubans, bound by affection and solidarity, must continue to work with serenity, security and discipline to successfully confront the new coronavirus, as President Miguel Díaz-Canel indicated.

On an individual level, this means not losing track of reality and looking at the faces of others with our hands on our hearts. In this way, we accompany the country’s decisions and do not fail in the will that guides us in this battle.

It is a struggle in which we are all involved, of a social nature, and in which each one must impose on themselves the condition of being responsible, for your own good and for that of others. For the time being, we must postpone some customary habits. It is convenient for everyone, for you and for me. It is the most prudent thing to do.

Canadian First Nations on Health Coop with Cuba

Canadian First Nations on Health Cooperation with Cuba

By Lisandra Romeo Matos and Lisandra Fariñas Acosta

By Lisandra Romeo Matos and Lisandra Fariñas Acosta

Cubadebate journalist. Degree in Journalism (2011), Universidad de Oriente. Worked at the Cuban News Agency (2011-2018).

February 28, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Jerry Daniels, the great chief of southern Manitoba and the Southern Chiefs Organization (centre), with chief Dave Ledoux of the Gambler Pueblo (left) and chief Nelson Genaille of the Sapotewayak Cree nation in northern Manitoba (right). Photo: Cubadebate.

First Nations leaders and health technicians from Manitoba and Alberta in Canada expressed their communities’ interest in establishing cooperation links with Cuba in the field of health.

After a week in Havana, where they toured several institutions in the sector and held meetings with authorities in the field, including the head of the country, Dr. José Ángel Portal Miranda, they announced this Friday at a press conference their growing desire that the Island be able to provide them with professionals trained in basic health services, who can attend to the needs of these for decades marginalized communities.

Jerry Daniels, the great chief of the southern region of Manitoba, and of the Organization of the Chiefs of the South, which represents 34 of the more than 600 native nations of Canada, said at Hotel Nacional de Cuba that these peoples “have been limited in their access to health care provided by the government,” and that is why they demand health care providers and various services in these communities.

He said that these communities “are in the midst of a process of transformation of care services, aimed particularly at creating and facilitating access, not only in infrastructure, but also in decision-making and training of professionals.

What we all agree on is that we need many more providers and access to health care, quality services, and professionals to assist these communities, especially in the most remote ones,” he remarked.

According to Daniels, Cuba has a structure in place and is recognized for using it, in addition to having cooperation programs consisting of sending health professionals to various nations, where they do their work with quality and contribute to saving lives even in the most difficult to reach regions.

He added that the Cuban government “can help in two fundamental aspects: sending doctors and other professionals to work in our communities to provide health services, and training specialists at the Latin American School of Medicine to return and cover existing health needs.

We are pleased to imagine that hundreds of health professionals will come to our communities and heal women, children, the elderly and other vulnerable populations. It would be a truly promising future, the native leader argued.

According to Daniel, another impact would be that by improving access to health care in these communities, in a more just and professional way, the migration of these populations to the cities in search of these services would be reduced.

“We want our communities to have health posts, hospitals and other assistance centers, and I urge the other chiefs of the first nations to open up to this possibility of collaboration with Cuba, which we need so much,” he said.

He called for accelerating the process of finding solutions to reverse existing health problems in these locations, such as diabetes, cancer, among other factors. “That is why we are here and we call on all world leaders to help us find solutions to provide better, quality health systems,” he summarized.

First Nations leaders and health technicians from Manitoba and Alberta in Canada. Photo: Cubadebate.

For Chief Dave Ledoux of the Gambler Pueblo, the offer from Cuba to the native peoples in Canada corresponds to the Cuban health mission around the world since 1959.

The leader highlighted the recognition of the Island’s health system by the WHO, as well as the quality and its preventive and holistic model, which has allowed to achieve minimal infant mortality rates, and to increase the life expectancy of its population.

“Thousands of students from all over the world have come to Cuba to study the different medical specialties in the last 60 years,” he pondered, and emphasized that it would be an opportune moment for this offer of help, “since we are currently rebuilding our communities to get out of decades of systemic institutional oppression.

The health philosophy of this country and its values are very similar to the traditional medicine model of our peoples, said Deloux.

The more than 600 first nations in Canada include more than one million people who would benefit from these services, he said. He added that from these initial meetings in Havana they are optimistic and hope to apply the ideas, designs and organizational strategies observed in the Cuban health system.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

You must be logged in to post a comment.