Books 15

Intro to Cuban edition of A People’s History of Science

Introduction to the Cuban edition of

A People’s History of Science

(Historia Popular de la Ciencia)

By Clifford D. Conner

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

When I learned that an edition of A People’s History of Science would be published in Cuba, it occurred to me that in no country in the world would readers be more likely to appreciate its central theme, which is that science is not and never has been the exclusive province of a few elite geniuses. President Castro himself made that point very succinctly in a National Science Day speech on January 15, 1992. In Cuba, he said, “there are hundreds of thousands of scientists. Even the individual that manufactures the small parts and looks for solutions is a scientist and an investigator of a sort.”

This book is a general survey of a very large subject, and does not pretend to be all-inclusive. One particular area to which it accorded insufficient attention was the science of the twentieth century, and especially the relationship of science to the great revolutionary events that occurred in Russia, China, and Cuba. I will try to at least partially remedy that deficiency now.

Throughout history, revolutions have tended to create positive conditions for the development of science by removing obstacles to innovative thought and practice. In the process of “turning the world upside down,” revolutions have typically eliminated censorship and broken the institutional power of entrenched intellectual elites that stifled science. Furthermore, by liberating subordinate social classes, revolutions have brought many more actors onto the stage of history. The resulting vast increase in the number of people able to play an active role in shaping their lives has enhanced all fields of human endeavor, including science.

Revolutions in the twentieth century have also encouraged the development of science in other ways. From Russia to Vietnam, science became a major governmental priority wherever revolutions guided by Marxist parties occurred. The socialist revolutions that replaced market-controlled economies with centrally planned economies have been able to marshal resources and focus attention on scientific goals to an unprecedented degree and with unprecedented results. “National liberation” revolutions in poorer countries have broken the chains of imperialist domination that had previously restricted them to the low-tech role of raw-materials suppliers. Being free to create their own modern industries naturally stimulated their interest in modern science and technology.

Science and the Russian Revolution

“The Bolsheviks who took over Russia in 1917,” Loren Graham writes in Science in Russia and the Soviet Union, “were enthusiastic about science and technology. Indeed, no group of governmental leaders in previous history ever placed science and technology in such a prominent place on their agenda.” The results proved to be momentous. “In a period of sixty years the Soviet Union made the transition from being a nation of minor significance in international science to being a great scientific center. By the 1960s Russian was a more important scientific language than French or German, a dramatic change from a half-century earlier.” The Soviet Union’s ascension to international scientific leadership was strikingly confirmed when it became the first country to launch an artificial satellite and to put an astronaut into orbit.

Lenin’s appreciation of the value of science-based technology is apparent in his famous definition of communism as “Soviet power plus the electrification of the entire country.” But despite Lenin’s desires and intentions, scientific development got off to a slow start in the early years of the Soviet Union. Efforts to promote research were severely hampered not only by the war-ravaged country’s shortage of material resources, but by a deficiency of scientific talent caused by the exodus of many scientists who were hostile to the revolution. Nor did it help that a large proportion of the scientifically and technically trained specialists who did not emigrate were unsympathetic to the Bolshevik regime. More than a decade after the 1917 revolution, fewer than two percent of the Soviet Union’s engineers—138 out of about 10,000—were Communist cadres.

Nonetheless, Lenin believed it would be counterproductive to try to forcibly impose the Bolshevik will on the recalcitrant scientists and engineers. Totalitarian control of scientific institutions was not his policy but Stalin’s. At the end of 1928 the Imperial Academy of Sciences, a Czarist institution, not only continued to exist but was still the most prestigious of scientific bodies, and not one of its academicians belonged to the Communist Party. It was not until the 1929–32 period, when Stalin was well on his way toward assuming complete command, that the Communist Party took over the Academy and reorganized it.

In the first years of the revolution, an ultra-radical current within the Communist movement demanded the “proletarianization” of science and the dismissal of the “bourgeois” experts. Lenin vigorously opposed this Proletkult movement, which he characterized as infantile and irresponsible. Lenin’s great authority was able to hold the Proletkult campaign at bay for a number of years, but after his death Stalin demagogically manipulated it for factional purposes. In the years 1928–31 he promoted a Cultural Revolution (later to be imitated by Mao Zedong in China) that once again counterposed “proletarian science” to “bourgeois science.” Purges of scientists and campaigns to ensure political conformity caused chaos and disruption within the scientific institutions. Scientific education was paralyzed as the works of Einstein, Mendel, Freud, and others were condemned as bourgeois science and banned from the universities.

Meanwhile, however, the relentless pressure of external threats to the Soviet Union allowed Stalin to rally support, consolidate his power, and impose a program of rapid industrialization and agricultural collectivization requiring significant input from the sciences. Compulsory centralized planning plus massive funding rapidly gave birth to “Big Science” in the Soviet Union. The result was the creation of a powerful, but distorted, science establishment.

The limitations Stalin’s policies imposed on free inquiry acted as a counterweight to the revolution’s great gift to Russian science, which was the ability of the centralized economy to marshal and organize resources. Although the Soviet Union rose close to the top of the science world—second only to the United States—in the final analysis, its record was disappointing. In spite of its success in accomplishing some very impressive large-scale technological feats—hydroelectric power plants, nuclear weapons, earth-orbiting satellites, and the like—the achievements of the Soviet science establishment, given its immense size, fell far short of what might have been expected of it.

The demise of the Soviet Union in 1991 caused it to forfeit the strong position it had gained in international science. A 1998 assessment by the U.S. National Science Foundation reported that with regard to Russia and the other spinoffs of the former Soviet Union, science in those countries is on the edge of extinction, surviving only by means of charitable donations from abroad.

Science and the Chinese Revolution

Just as World War One gave rise to a Marxist-led revolution in Russia, so did World War Two facilitate the victory of a revolution in China under the aegis of a Communist Party. In 1949 the People’s Republic of China was proclaimed and the remnants of the Guomindang regime fled to Taiwan. The revolution brought to power a government that for the first time had the will and the ability to create institutions of Big Science, as had previously been done in the Soviet Union.

Soviet science provided more than simply a model for Mao Zedong’s regime. In the 1950s Soviet scientists and technicians participated heavily in the construction of science in the new China and they created it in their own image. However, there were strings attached—Stalin expected the Chinese to submit to Soviet control—and that led to problems.

Stalin had originally pledged full support to the effort to replicate Soviet Big Science in China, including the development of nuclear weapons. But there were sharp limits to the Kremlin’s spirit of proletarian solidarity. When the Mao regime began to show signs of resistance to Soviet control, Soviet leaders apparently had second thoughts about creating a nuclear power in a large country with which it had a long common border. They reneged on their promise to share nuclear technology, precipitating a deep and bitter Sino-Soviet split.

In June 1960, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev abruptly ordered the withdrawal of all aid from China. Thousands of Soviet scientists and engineers were called home immediately, taking their blueprints and expertise with them. It was a ruthless act of sabotage that dealt a crushing blow not only to Chinese science but to the country’s economic and industrial development as a whole.

Although set back several years, the goal of constructing a Soviet-style science establishment endured. The Soviet formula of heavily bureaucratized central planning plus massive funding produced similar mixed results in China. With very little foreign assistance, strategic nuclear weapons were developed and satellites were launched into space—both extremely impressive feats. Nonmilitary science and technology in Chinese industries and at the research institutes and universities, however, remained at a relatively primitive level.

In spite of the devastating blow caused by the Soviet Union’s withdrawal of support, China accomplished some remarkable achievements in nuclear and space technology—a testament to the power of the planned economy to mobilize and focus resources against all odds. The country tested its first atomic bomb in 1964 and its first hydrogen bomb in 1967, and launched its first satellite into Earth orbit in 1970—number one in a series of scores of space probes leading up to 2003, when China became only the third nation to independently send an astronaut into space. The science establishment, however, has remained highly bureaucratized and focused on military and big industrial projects at the expense of research aimed at improving the lives of the billion-plus people of China.

It is undeniable that the centralization and planning made possible by the 1949 revolution is at the root of China’s transformation from a negligible factor to a major player on the international science scene—perhaps even the primary future challenger to the United States’ dominance. Yet the mass of the Chinese population continues to endure a material standard of living far below that of the people of Europe, Japan and the United States. That an orientation more centered on human needs is possible has been demonstrated by a revolution that occurred in a much smaller country.

The people-oriented science of the Cuban Revolution

In the first week of 1959 revolutionary forces under the banner of the July 26th Movement entered Havana and established a new government. As events unfolded, the revolution’s leaders soon found themselves embroiled in conflict with the United States. They came to believe that economic sabotage by pro–United States industrialists operating within Cuba could only be prevented by nationalizing the Cuban economy and declaring a governmental monopoly of foreign trade. As United States–owned firms were nationalized, Cuba’s confrontation with its mighty neighbor deepened, and for protection the new regime entered into an alliance with the Soviet Union.

Once the revolution’s leaders were in command of a fully nationalized economy, they enjoyed the same advantages that had enabled their Soviet and Chinese counterparts to develop powerful science establishments. The situation in Cuba, however, was considerably different: The earlier revolutions had occurred in two of the world’s largest countries, but Cuba was a small island with a population of only about ten million people. Its scientific endeavors, therefore, were not channeled into a quixotic effort to compete directly with the United States in the field of military technology. Instead, Cuba would depend on diplomatic and political means for its national security—that is, on its alliance with the Soviet Union and on the moral authority its revolution had gained throughout Latin America and the rest of the world. That allowed its science establishment to direct its attention in other, less military-oriented, directions.

The USSR and China had both sought to build powerful, autonomous economies that could go head-to-head in competition with the world’s leading capitalist nations. With that in mind, they aimed their science efforts at facilitating the growth of basic heavy industry. The Cubans, by contrast, oriented their science program toward the solution of social problems. Scientific development, they decided, depended first of all on raising the educational level of the entire population. Before the revolution, almost 40 percent of the Cuban people were illiterate. In 1961 a major literacy campaign was launched that reportedly resulted in more than a million Cubans learning to read and write within a single year. Today the literacy rate is 97 percent and science education is a fundamental part of the national curriculum.

In addition to education, universal healthcare was assigned high priority, giving impetus to the development of the medical sciences. A harsh economic embargo imposed by the United States compelled the Cubans to find ways to produce their own medicines. They met the challenge and the upshot was that Cuba, despite its “developing world” economic status, now stands at the forefront of international biochemical and pharmacological research.

As evidence of the success of their medical programs, Cuban officials point to comparative statistics routinely used to quantify the well-being of nations, the most informative measures being average life expectancy and infant mortality. In both categories, Cuba has risen to rank among the wealthiest industrialized nations. Richard Levins, a professor at Harvard University’s School of Public Health, contends that “Cuba has the best healthcare in the developing world and is even ahead of the United States in some areas such as reducing infant mortality.” As for life expectancy, the CIA’s World Factbook statistics for 2006 report that the average lifespan in Cuba of 77.41 years earns it a rank of 55th out of 226 countries, while the United States’ average of 77.85 years puts it slightly higher, in 48th place.

Another key indicator of the quality of a nation’s healthcare system is the doctor-to-patient ratio. According to the World Health Organization’s statistics for 2006, out of 192 countries in the world, Cuba ranks first in that category: There is one doctor for every 170 people in Cuba, compared, for example, with one doctor per 390 in the United States, per 435 in the United Kingdom, per 238 in Italy, and per 297 in France. Most of the nations of the developing world have fewer than one doctor per 1,000 inhabitants.

The abundance of Cuban medical practitioners today is especially remarkable considering that in reaction to the nationalization of medical services in 1960 almost half of the island’s physicians emigrated to the United States, leaving only about 3,000 doctors and fewer than two dozen medical professors. In 1961 the revolutionary government addressed that problem by constructing medical teaching facilities. Today, according to the World Health Organization, thirteen medical schools are in operation in Cuba.

The doctor-to-patient ratio only tells part of the story, because Cuba’s medical schools in fact produce a large surplus of physicians—far more than can be put to productive use on the island itself. As a result, Cuba has actively exported its doctors to other parts of the world. The itinerant Cuban physicians do not “follow the money”—they go to parts of the developing world most in need of healthcare services. With the stated ambition of becoming a “world medical power,” Cuba offers more humanitarian medical aid to the rest of the world than does any other country, including the wealthy industrialized nations. The Cuban government has more doctors working throughout the world than does the World Health Organization.

A January 17, 2006, BBC News report stated: “Humanitarian missions in 68 countries are manned by 25,000 Cuban doctors, and medical teams have assisted victims of both the Tsunami and the Pakistan earthquake. In addition, last year 1,800 doctors from 47 developing countries graduated in Cuba. . . . Under a recent agreement, Cuba has sent 14,000 medics to provide free health care to people living in Venezuela’s barrios, or shantytowns, where many have never seen a doctor before.” In addition to the medical equipment, medicines, and the services of doctors it has provided throughout the developing world, Cuba has also helped to build and staff medical schools in Ethiopia, Guinea-Bissau, and Yemen.

Cuba’s healthcare successes have been closely linked to the pioneering advances its laboratories have produced in the medical sciences. In the 1980s a worldwide “biotechnological revolution” occurred, and Cuban research institutions took a leading role in it. Among the most noteworthy products of Cuban bioscience are vaccines for treating meningitis and hepatitis B, the popular cholesterol-reducer PPG (which is derived from sugarcane), monoclonal antibodies used to combat the rejection of transplanted organs, recombinant interferon products for use against viral infections, epidermal growth factor to promote tissue healing in burn victims, and recombinant streptokinase for treating heart attacks.

The Cuban biotech institutes focus their attention on deadly diseases that “Big Pharma” (the profit-motivated multinational drug corporations) tends to ignore because they mainly afflict poor people in the developing world. An important part of their mission is the creation of low-cost alternative drugs. In 2003 Cuban researchers announced the creation of the world’s first human vaccine containing a synthetic antigen (the “active ingredient” of a vaccine). It was a vaccine for treating Hib (Haemophilus influenzae type b), a bacterial disease that causes meningitis and pneumonia in young children and kills more than 500,000 throughout the world every year. An effective vaccine against Hib already existed and had proven successful in industrialized nations, but its high cost sharply limited its availability in the less affluent parts of the world. The significantly cheaper synthetic vaccine has already been administered to more than a million children in Cuba and is currently being introduced into many other countries.

The Cuban example offers a particularly clear case study of how a revolution has contributed to the development of science. The Cuban revolution removed the greatest of all obstacles to scientific advance by freeing the island from economic subordination to the industrialized world. The wealthier countries’ ability to manufacture products at relatively low cost allows them to flood the markets of the nonindustrialized countries with cheaply produced machine-made goods, effectively preventing the latter from industrializing. The only way out of this dilemma for the poorer countries is to remove themselves from the worldwide economic system based on market exchange, where the rules are entirely stacked against them. The history of the twentieth century, however, suggests that any countries wanting to opt out of the system have had to fight their way out. The Cuban revolution was therefore a necessary precondition of the creation and flowering of Cuban science and its biotechnology industry.

The scientific achievements of the Cuban revolution testify that important, high-level scientific work can be performed without being driven by the profit motive. They also show that centralized planning does not necessarily have to follow the ultrabureaucratized model offered by the Soviet Union and China, wherein science primarily serves the interests of strengthening the state and only secondarily concerns itself with the needs of the people. Cuba’s accomplishments are all the more impressive for having been the product of a country with a relatively small economic base, and with the additional handicap of an economic embargo imposed by a powerful and hostile neighboring country.

The Cuban revolution has come closest to realizing the noble goal of a fully human-oriented science. Although Cuba’s small size limits its usefulness as a basis for universal conclusions, its accomplishments in the medical sciences certainly provide reason to believe that science on a world scale could be redirected from its present course as a facilitator of blind economic growth (which primarily serves the interests of small ruling groups that control their countries’ economies) and instead be devoted to improving the wellbeing of entire populations.

The Vietnam War and the People of the U.S.

The Vietnam War and the People of the United States

By Manuel E. Yepe

Exclusive for daily POR ESTO! of Mérida, México.

http://manuelyepe.wordpress.com/

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

“Two of the world’s greatest revolutionaries –Jose Marti and Ho Chi Minh– lived for some time in the United States.

Both had deep knowledge of US history and culture. Both saw the dark side of that nation, but also acknowledged great revolutionary potential in the democratic ideals of the United States. The Vietnamese Ho Chi Minh wrote about the Ku Klux Klan and lynching, while, in the 19th Century, Cuban Jose Martí warned against the evidence of the coming advent of imperialism in North America.”

The quotation is from “Vietnam and Other American Fantasies,” a book by Bruce H. Franklin (b.1934), the multiple award-winning scholar and writer on historical cultural topics.

Franklin’s book attempts to demolish the fantasies, myths, and lies that most people in the United States believe about the relatively recent Vietnam War. It uncovers the truth about what was really an imperialist war against the people of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

That war was rejected by the heroic struggle of tens of millions of people in the US. The dominant narrative today in the United States claim there was a democratic nation called South Vietnam, and another evil one called North Vietnam that was part of a communist imperial dictatorship. North Vietnam wished to invade South Vietnam.

The United States, being the leader of the free world and the defender of democracy on Earth, had to go to South Vietnam in 1965 to defend it and got bogged down in a quagmire. “We could not win the war because we fought with one hand tied behind our back, because of some university students mobilized by veteran left-leaning professors and the actress Jane Fonda.”

In his book, Franklin explains that Vietnam was a single country, not two countries. The US war against Vietnam began in 1945, not in 1965. The anti-war movement was initiated by US soldiers and sailors who were its vanguard, and in the endydct k made it impossible for Washington to continue the war in 1945.

Between 1945 and 1975 the Vietnamese revolution led the global struggle against colonialism that brought independence to half the world’s population. During those three decades, the US struggled to preserve colonialism and became the leader of neo-colonialism, the ultimate form of imperialism in the world.

Franklin recalls the true story of the day when Japan surrendered: August 14, 1945, recalling his experiences that day, when he was eleven years old. He was riding in a van full of children in joyful celebration in the streets of the Brooklyn neighborhood where he then lived. “We believed in a future of peace and prosperity, quite different from that of a nation always at war, as we live in now.”

That day in August was the beginning of the revolution in Vietnam, when the Vietnamese people rose and, in less than three weeks, defeated the Japanese and the French and established the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

On September 2, Ho Chi Minh read out the declaration of independence to half a million Vietnamese in Hanoi, the former capital of a new nation that had been fighting for independence for over 2,000 years.

Suddenly, two fighter planes appeared above the crowd. When the Vietnamese recognized US insignia on the planes, they shouted for joy. They believed that the Americans were their friends and allies, and that they were the champions of freedom and independence from colonialism.

Washington, however, conspired with Paris to launch an invasion against the Democratic Republic of Vietnam whose goal was to restore French colonial rule. The United States would provide arms and financing. This, Franklin points out, was the true beginning of the war against Vietnam and marks the beginning of the US people’s movement against that war.

The British troops who had been sent to Saigon to disarm the remaining Japanese forces, instead gave weapons to the Japanese who had been recently disarmed by the Vietnamese. Soon the Japanese joined the British together with the remnants of the French colonial forces to wage war against the newly-declared independent nation of Vietnam.

When Washington later decided to replace France in the war against Vietnam, fierce opposition from US citizens prevented it, and for that reason, direct US military involvement had to be initially disguised.

Bruce H. Franklin recalls that, although it was the struggle of the Vietnamese which defeated the United States, the anti-war movement, especially in the armed forces, ultimately forced Washington to sign a peace treaty that included, word by word, each demand of the victorious Vietnamese liberation forces.

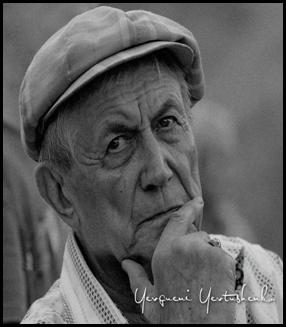

Yevgeny Yevtushenko in Cuba, 2016

- English

- Español

Yevgeny Yevtushenko in Cuba, 2016

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

UNEAC [Unión Nacional de Escritores y Artistas de Cuba/ National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba] is pleased to invite you to a Conversation Session with Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, screenwriter along with Enrique Pineda Barnet of the film Soy Cuba. Filmmakers from ICAIC [Instituto Cubano de Arte e Industria Cinematográficos/Cuban Film Institute] will also be present. The event will be on Thursday 26 at 10:00 am as part of the activities of the International Poetry Festival: an occasion when dramaturgy, film and poetry converge.

The poet received the name with which he became famous in 1944 when his mother, returning from evacuation in Zimmah, changed the boy’s father’s name to her maiden name. Later, Yevtushenko wrote about this event in his poem “Mom and the Neutron Bomb”. It was during that process that they consciously registered him as having been born in 1933 in order to avoid the complications that would have meant obtaining the necessary safe-conduct for all persons aged 12 years of age.

On June 4, 1949, one of his poems is first published: It was “Two Sports” published in the newspaper Sovietskii Sport. Three years later his first collection of poems “The Explorers of the Future” was released; and that same year of 1952 he joined the Union of Soviet Writers becoming its youngest member.

Along with Andrei Voznesensky, Róbert Rozhdestvenski and Bella Akhmadulina, Yevtushenko was one of the idols of the nineteen-sixties generation and quotations from his works were transformed into proverbial phrases, for example, “A poet in Russia is more than a poet.”

He toured the world in his many travels and his relationship with the Hispanic world has been special: he learned Spanish and translated into Russian the work of some poets like the Chilean Raúl Zurita. One night, on the banks of the Amazon River in Leticia, Colombia, he saw a huge fire on the other side, on the south bank of the river.

He asked his friends if they should not all cross the Amazon to help extinguish the fire. They said, “No matter, that is the Peruvian side.” This made Yevtushenko write a poem in Spanish:

No hay lado colombiano,

No hay lado peruano.

Solamente hay lado humano.

[There is not a Colombian side,

There is not a Peruvian side,

There is only a Human side.]

Works

Books in Spanish

- No he nacido tarde , Horizonte, Madrid, 1963

- El dios de las gallinas , Guadalorce, Málaga, 1966.

- Autobiografía precoz , Era, México

- Entre la ciudad sí y la ciudad no , tr.: Jesús López Pacheco y Natalia Ivanova; Alianza, Madrid, 1969

- ¡Escuchadme ciudadanos! Versos y poemas: 1959-64 , tr.: José María Guell; Ediciones 29, Barcelona, 1977

- Siberia tierra de bayas”, Planeta, Barcelona, 1981.

- Adiós, Bandera Roja. Selección de poesía y prosa (1953-1996) , Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1997, ISBN 968-16-5420-X , ISBN 978-968-16-5420-7

- No mueras antes de morir , tr.: Helena S. Kriúkova y Vicente Cazcarra; Anaya & Mario Muchnik. Barcelona, 1997

Poems

- «Станция Зима» (1953—1956) – Estación de Zimá (La estación Invierno)

- “Бабий Яр” (1961) – Babi Yar

- «Братская ГЭС» (1965)- Сentral hidroeléctrica de Bratsk

- «Пушкинский перевал» (1965) – El puerto de Pushkin

- «Коррида» (1967) – Corrida

- «Под кожей статуи Свободы», (1968) – Bajo de la piel de la estatua de la Libertad

- «Казанский университет», (1970) – La universidád de Kazán

- «Снег в Токио», (1974) – Nieve en Tokio

- «Ивановские ситцы», (1976)- Los percales de Ivánovo

- «Северная надбавка», (1977) – La prima para norteños

- «Голубь в Сантьяго», (1978) – La paloma en Santiago (de Chile)

- «Непрядва», (1980) – Nepriádva ( Batalla de Kulikovo )

- «Мама и нейтронная бомба», (1982) – Mamá y la bomba de neutrones

- «Дальняя родственница» (1984) – Pariente lejana

- «Фуку!» (1985)- Fukú!

- «Тринадцать» (1996) – Trece

- «В полный рост» (1969—2000) – A plena estatura

- «Просека» (1975—2000) – Entresaca

Poetry Collections

- «Разведчики грядущего» (1952) – Los exploradores del porvenir

- «Третий снег» (1955) – La tercera nieve

- «Шоссе Энтузиастов» (1956)- La carretera de Entusiastas

- «Обещание» (1957) – Promesa

- «Взмах руки» (1962) – El braceo

- «Нежность» (1962) – Ternura

- «Катер связи» (1966) – Lancha de enlace

- «Идут белые снеги» (1969) – Nieva

- «Интимная лирика» (1973) – Lírica íntima

- «Утренний народ» (1978) – La gente de madrugada

- «Отцовский слух» (1978) – Oído del padre

- “Последняя попытка” (1990) – Prueba última

- “Моя эмиграция” (1991) – Mi emigración

- “Белорусская кровинка” (1991) – Sangre Bielorrusa

- “Нет лет” (1993) – No hay veranos

- “Золотая загадка моя” (1994) – Mi adivinanza de oro

- “Поздние слёзы” (1995) – Lágrimas tardías

- “Моё самое-самое” (1995) – Mi mejor de lo mejor

- “Бог бывает всеми нами…” (1996) – Díos suele ser nosotros

- “Медленная любовь” (1997) – Amor lento

- “Невыливашка” (1997) – Tintero no-se-derrama

- “Краденые яблоки” (1999) – Manzanas robadas, Visor Libros, 2011

- “Между Лубянкой и Политехническим” (2000) – Entre la Lubianka y el Politécnico

- “Я прорвусь в двадцать первый век…” (2001) – Yo me abriré paso al siglo XXI

Novels

- «Ягодные места» (1982) – Tierra de bayas ( Siberia )

- «Не умирай прежде смерти» (1993) – No mueras antes de morir, tr.: Helena S. Kriúkova y Vicente Cazcarra; Anaya & Mario Muchnik. Barcelona, 1997

Short Novels

- «Пирл-Харбор» (“Мы стараемся сильнее”)(1967) – Pearl Harbour

- «Ардабиола» (1981) – Ardabiola, Mondadori, 1989

Essay Collections

- “Autobiografía” París, 1963

- «Талант есть чудо неслучайное» (1980) – El talento es un milagro no casual

- «Волчий паспорт» (1998) – Сertificado personal de recusación (memorias)

Music

- “Sinfonía Nº 13” (1962) – Sinfonía coral de Dmitri Shostakóvich basada en el poema Babi Yar

- “Ejecución de Stenka Razin ” (1965) – Cantata de Dmitri Shostakóvich con versos de Yevtushenko

- “Nieva” (“Идут белые снеги”) (2007) – Ópera rock, música de Gleb May

Films

- “Soy Cuba” (1964) – Guionista.

- “Jardín de infancia” (1984) – Director y Guionista.

- “El entierro de Stalin” (“Pójorony Stálina”), (1990) – Director y Guionista.

Awards and decorations

- Orden de la Insignia de Honor, 1969 (URSS)

- Orden de la Bandera Roja del Trabajo, 1983 (URSS)

- Premio Estatal de la URSS 1984 por Mamá y la bomba de neutrones

- Orden de la Amistad de los Pueblos, 1993 (lo rechazó en señal de protesta contra la guerra en Chechenia ) (Rusia)

- Orden Leyenda Viva, 2003 (Ucrania)

- Orden de Honor, 2003 (Georgia)

- Premio Tsárskoye Seló 2003 (Rusia)

- Premio Fregene de Literatura 1981 (Italia)

- Academia SIMBA (Italia) 1984

- Premio Tizian Tabidze (Georgia)

- Premio Ianis Rainis (Letonia)

- Premio Enturia (Italia)

- Premio Triada (Italia)

- Premio Walt Whitman (EE.UU)

- Premio Aquila 2002 (Italia)

- Premio Grinzane Cavour 2005 (Italia)

- Comendador de la Orden de Bernardo O’Higgins 2009 (Chile)

- Premio Estatal de la Federación de Rusia 2009

- Premio Poeta 2013 (Rusia)

- Premio alla carriera. Festival Virgilio 2016 (Italia)

——————————————————

La UNEAC tiene el placer de invitarlos al Conversatorio con el poeta ruso Evgueni Evtushenko, guionista junto con Enrique Pineda Barnet, de la película Soy Cuba, con la presencia realizadores del ICAIC. La cita será el jueves 26 a las 10:00 a.m. como parte de las actividades del Festival Internacional de Poesía. Una ocasión donde converge la dramaturgia, el cine y la poesía.

Este poeta obtuvo el apellido con el que se haría famoso en 1944 cuando su madre, de regreso de la evacuación en Zimá, le cambió el apellido del padre por el suyo de soltera, hecho sobre el que Yevtushenko escribiría más tarde en su poema Mamá y la bomba de neutrones. Fue al hacer ese trámite que conscientemente lo registraron como nacido en 1933 con el fin de evitarse las complicaciones que hubiera significado obtener el salvoconducto necesario para todas las personas a partir de los 12 años de edad.

El 4 de junio de 1949 aparece publicado por primera vez un poema suyo: se trata de Dos deportes publicado en el periódico Sovietski Sport. Tres años más tarde sale su primer poemario: Los exploradores del porvenir y ese mismo año de 1952 es aceptado en la Unión de Escritores Soviéticos convirtiéndose en su miembro más joven.

Junto con Andréi Voznesenski , Róbert Rozhdéstvenski y Bela Ajmadúlina , Yevtushenko fue uno de los ídolos de la generación de los sesenta y citas de sus obras se transformaron en frases proverbiales, por ejemplo, “Un poeta en Rusia es más que un poeta”.

Recorrió el planeta en sus innumerables viajes y su relación con el mundo hispano ha sido especial: aprendió español y tradujo al ruso a algunos poetas como el chileno Raúl Zurita. Una noche, a orillas del Amazonas, en Leticia, Colombia, vio un tremendo incendio al otro lado, en la ribera sur del río. Preguntó a sus amigos si no debían todos cruzar el Amazonas para ayudar a apagar el fuego. Le contestaron: “No importa, es del lado peruano.” Esto dio motivo a que Yevtushenko escribiera un poema en castellano:

No hay lado colombiano,

No hay lado peruano.

Solamente hay lado humano.

Obras

Libros en español

- No he nacido tarde , Horizonte, Madrid, 1963

- El dios de las gallinas , Guadalorce, Málaga, 1966.

- Autobiografía precoz , Era, México

- Entre la ciudad sí y la ciudad no , tr.: Jesús López Pacheco y Natalia Ivanova; Alianza, Madrid, 1969

- ¡Escuchadme ciudadanos! Versos y poemas: 1959-64 , tr.: José María Guell; Ediciones 29, Barcelona, 1977

- Siberia tierra de bayas”, Planeta, Barcelona, 1981.

- Adiós, Bandera Roja. Selección de poesía y prosa (1953-1996) , Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1997, ISBN 968-16-5420-X , ISBN 978-968-16-5420-7

- No mueras antes de morir , tr.: Helena S. Kriúkova y Vicente Cazcarra; Anaya & Mario Muchnik. Barcelona, 1997

Poemas

- «Станция Зима» (1953—1956) – Estación de Zimá (La estación Invierno)

- “Бабий Яр” (1961) – Babi Yar

- «Братская ГЭС» (1965)- Сentral hidroeléctrica de Bratsk

- «Пушкинский перевал» (1965) – El puerto de Pushkin

- «Коррида» (1967) – Corrida

- «Под кожей статуи Свободы», (1968) – Bajo de la piel de la estatua de la Libertad

- «Казанский университет», (1970) – La universidád de Kazán

- «Снег в Токио», (1974) – Nieve en Tokio

- «Ивановские ситцы», (1976)- Los percales de Ivánovo

- «Северная надбавка», (1977) – La prima para norteños

- «Голубь в Сантьяго», (1978) – La paloma en Santiago (de Chile)

- «Непрядва», (1980) – Nepriádva ( Batalla de Kulikovo )

- «Мама и нейтронная бомба», (1982) – Mamá y la bomba de neutrones

- «Дальняя родственница» (1984) – Pariente lejana

- «Фуку!» (1985)- Fukú!

- «Тринадцать» (1996) – Trece

- «В полный рост» (1969—2000) – A plena estatura

- «Просека» (1975—2000) – Entresaca

Libros de versos

- «Разведчики грядущего» (1952) – Los exploradores del porvenir

- «Третий снег» (1955) – La tercera nieve

- «Шоссе Энтузиастов» (1956)- La carretera de Entusiastas

- «Обещание» (1957) – Promesa

- «Взмах руки» (1962) – El braceo

- «Нежность» (1962) – Ternura

- «Катер связи» (1966) – Lancha de enlace

- «Идут белые снеги» (1969) – Nieva

- «Интимная лирика» (1973) – Lírica íntima

- «Утренний народ» (1978) – La gente de madrugada

- «Отцовский слух» (1978) – Oído del padre

- “Последняя попытка” (1990) – Prueba última

- “Моя эмиграция” (1991) – Mi emigración

- “Белорусская кровинка” (1991) – Sangre Bielorrusa

- “Нет лет” (1993) – No hay veranos

- “Золотая загадка моя” (1994) – Mi adivinanza de oro

- “Поздние слёзы” (1995) – Lágrimas tardías

- “Моё самое-самое” (1995) – Mi mejor de lo mejor

- “Бог бывает всеми нами…” (1996) – Díos suele ser nosotros

- “Медленная любовь” (1997) – Amor lento

- “Невыливашка” (1997) – Tintero no-se-derrama

- “Краденые яблоки” (1999) – Manzanas robadas, Visor Libros, 2011

- “Между Лубянкой и Политехническим” (2000) – Entre la Lubianka y el Politécnico

- “Я прорвусь в двадцать первый век…” (2001) – Yo me abriré paso al siglo XXI

Novelas

- «Ягодные места» (1982) – Tierra de bayas ( Siberia )

- «Не умирай прежде смерти» (1993) – No mueras antes de morir, tr.: Helena S. Kriúkova y Vicente Cazcarra; Anaya & Mario Muchnik. Barcelona, 1997

Novelas cortas

- «Пирл-Харбор» (“Мы стараемся сильнее”)(1967) – Pearl Harbour

- «Ардабиола» (1981) – Ardabiola, Mondadori, 1989

Libros de ensayos

- “Autobiografía” París, 1963

- «Талант есть чудо неслучайное» (1980) – El talento es un milagro no casual

- «Волчий паспорт» (1998) – Сertificado personal de recusación (memorias)

Música

- “Sinfonía Nº 13” (1962) – Sinfonía coral de Dmitri Shostakóvich basada en el poema Babi Yar

- “Ejecución de Stenka Razin ” (1965) – Cantata de Dmitri Shostakóvich con versos de Yevtushenko

- “Nieva” (“Идут белые снеги”) (2007) – Ópera rock, música de Gleb May

Filmografía

- “Soy Cuba” (1964) – Guionista.

- “Jardín de infancia” (1984) – Director y Guionista.

- “El entierro de Stalin” (“Pójorony Stálina”), (1990) – Director y Guionista.

Premios y condecoraciones

- Orden de la Insignia de Honor, 1969 (URSS)

- Orden de la Bandera Roja del Trabajo, 1983 (URSS)

- Premio Estatal de la URSS 1984 por Mamá y la bomba de neutrones

- Orden de la Amistad de los Pueblos, 1993 (lo rechazó en señal de protesta contra la guerra en Chechenia ) (Rusia)

- Orden Leyenda Viva, 2003 (Ucrania)

- Orden de Honor, 2003 (Georgia)

- Premio Tsárskoye Seló 2003 (Rusia)

- Premio Fregene de Literatura 1981 (Italia)

- Academia SIMBA (Italia) 1984

- Premio Tizian Tabidze (Georgia)

- Premio Ianis Rainis (Letonia)

- Premio Enturia (Italia)

- Premio Triada (Italia)

- Premio Walt Whitman (EE.UU)

- Premio Aquila 2002 (Italia)

- Premio Grinzane Cavour 2005 (Italia)

- Comendador de la Orden de Bernardo O’Higgins 2009 (Chile)

- Premio Estatal de la Federación de Rusia 2009

- Premio Poeta 2013 (Rusia)

- Premio alla carriera. Festival Virgilio 2016 (Italia)

Spanish Headline Here

La UNEAC tiene el placer de invitarlos al Conversatorio con el poeta ruso Evgueni Evtushenko, guionista junto con Enrique Pineda Barnet, de la película Soy Cuba, con la presencia realizadores del ICAIC. La cita será el jueves 26 a las 10:00 a.m. como parte de las actividades del Festival Internacional de Poesía. Una ocasión donde converge la dramaturgia, el cine y la poesía.

La UNEAC tiene el placer de invitarlos al Conversatorio con el poeta ruso Evgueni Evtushenko, guionista junto con Enrique Pineda Barnet, de la película Soy Cuba, con la presencia realizadores del ICAIC. La cita será el jueves 26 a las 10:00 a.m. como parte de las actividades del Festival Internacional de Poesía. Una ocasión donde converge la dramaturgia, el cine y la poesía.

Este poeta obtuvo el apellido con el que se haría famoso en 1944 cuando su madre, de regreso de la evacuación en Zimá, le cambió el apellido del padre por el suyo de soltera, hecho sobre el que Yevtushenko escribiría más tarde en su poema Mamá y la bomba de neutrones. Fue al hacer ese trámite que conscientemente lo registraron como nacido en 1933 con el fin de evitarse las complicaciones que hubiera significado obtener el salvoconducto necesario para todas las personas a partir de los 12 años de edad.

El 4 de junio de 1949 aparece publicado por primera vez un poema suyo: se trata de Dos deportes publicado en el periódico Sovietski Sport. Tres años más tarde sale su primer poemario: Los exploradores del porvenir y ese mismo año de 1952 es aceptado en la Unión de Escritores Soviéticos convirtiéndose en su miembro más joven.

Junto con Andréi Voznesenski , Róbert Rozhdéstvenski y Bela Ajmadúlina , Yevtushenko fue uno de los ídolos de la generación de los sesenta y citas de sus obras se transformaron en frases proverbiales, por ejemplo, “Un poeta en Rusia es más que un poeta”.

Recorrió el planeta en sus innumerables viajes y su relación con el mundo hispano ha sido especial: aprendió español y tradujo al ruso a algunos poetas como el chileno Raúl Zurita. Una noche, a orillas del Amazonas, en Leticia, Colombia, vio un tremendo incendio al otro lado, en la ribera sur del río. Preguntó a sus amigos si no debían todos cruzar el Amazonas para ayudar a apagar el fuego. Le contestaron: “No importa, es del lado peruano.” Esto dio motivo a que Yevtushenko escribiera un poema en castellano:

No hay lado colombiano,

No hay lado peruano.

Solamente hay lado humano.

Obras

Libros en español

- No he nacido tarde , Horizonte, Madrid, 1963

- El dios de las gallinas , Guadalorce, Málaga, 1966.

- Autobiografía precoz , Era, México

- Entre la ciudad sí y la ciudad no , tr.: Jesús López Pacheco y Natalia Ivanova; Alianza, Madrid, 1969

- ¡Escuchadme ciudadanos! Versos y poemas: 1959-64 , tr.: José María Guell; Ediciones 29, Barcelona, 1977

- Siberia tierra de bayas”, Planeta, Barcelona, 1981.

- Adiós, Bandera Roja. Selección de poesía y prosa (1953-1996) , Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1997, ISBN 968-16-5420-X , ISBN 978-968-16-5420-7

- No mueras antes de morir , tr.: Helena S. Kriúkova y Vicente Cazcarra; Anaya & Mario Muchnik. Barcelona, 1997

Poemas

- «Станция Зима» (1953—1956) – Estación de Zimá (La estación Invierno)

- “Бабий Яр” (1961) – Babi Yar

- «Братская ГЭС» (1965)- Сentral hidroeléctrica de Bratsk

- «Пушкинский перевал» (1965) – El puerto de Pushkin

- «Коррида» (1967) – Corrida

- «Под кожей статуи Свободы», (1968) – Bajo de la piel de laestatua de la Libertad

- «Казанский университет», (1970) – La universidád de Kazán

- «Снег в Токио», (1974) – Nieve en Tokio

- «Ивановские ситцы», (1976)- Los percales de Ivánovo

- «Северная надбавка», (1977) – La prima para norteños

- «Голубь в Сантьяго», (1978) – La paloma en Santiago (de Chile)

- «Непрядва», (1980) – Nepriádva ( Batalla de Kulikovo )

- «Мама и нейтронная бомба», (1982) – Mamá y la bomba de neutrones

- «Дальняя родственница» (1984) – Pariente lejana

- «Фуку!» (1985)- Fukú!

- «Тринадцать» (1996) – Trece

- «В полный рост» (1969—2000) – A plena estatura

- «Просека» (1975—2000) – Entresaca

Libros de versos

- «Разведчики грядущего» (1952) – Los exploradores del porvenir

- «Третий снег» (1955) – La tercera nieve

- «Шоссе Энтузиастов» (1956)- La carretera de Entusiastas

- «Обещание» (1957) – Promesa

- «Взмах руки» (1962) – El braceo

- «Нежность» (1962) – Ternura

- «Катер связи» (1966) – Lancha de enlace

- «Идут белые снеги» (1969) – Nieva

- «Интимная лирика» (1973) – Lírica íntima

- «Утренний народ» (1978) – La gente de madrugada

- «Отцовский слух» (1978) – Oído del padre

- “Последняя попытка” (1990) – Prueba última

- “Моя эмиграция” (1991) – Mi emigración

- “Белорусская кровинка” (1991) – Sangre Bielorrusa

- “Нет лет” (1993) – No hay veranos

- “Золотая загадка моя” (1994) – Mi adivinanza de oro

- “Поздние слёзы” (1995) – Lágrimas tardías

- “Моё самое-самое” (1995) – Mi mejor de lo mejor

- “Бог бывает всеми нами…” (1996) – Díos suele ser nosotros

- “Медленная любовь” (1997) – Amor lento

- “Невыливашка” (1997) – Tintero no-se-derrama

- “Краденые яблоки” (1999) – Manzanas robadas, Visor Libros, 2011

- “Между Лубянкой и Политехническим” (2000) – Entre la Lubiankay el Politécnico

- “Я прорвусь в двадцать первый век…” (2001) – Yo me abriré paso al siglo XXI

Novelas

- «Ягодные места» (1982) – Tierra de bayas ( Siberia )

- «Не умирай прежде смерти» (1993) – No mueras antes de morir, tr.: Helena S. Kriúkova y Vicente Cazcarra; Anaya & Mario Muchnik. Barcelona, 1997

Novelas cortas

- «Пирл-Харбор» (“Мы стараемся сильнее”)(1967) – Pearl Harbour

- «Ардабиола» (1981) – Ardabiola, Mondadori, 1989

Libros de ensayos

- “Autobiografía” París, 1963

- «Талант есть чудо неслучайное» (1980) – El talento es un milagro no casual

- «Волчий паспорт» (1998) – Сertificado personal de recusación (memorias)

Música

- “Sinfonía Nº 13” (1962) – Sinfonía coral de Dmitri Shostakóvichbasada en el poema Babi Yar

- “Ejecución de Stenka Razin ” (1965) – Cantata de Dmitri Shostakóvich con versos de Yevtushenko

- “Nieva” (“Идут белые снеги”) (2007) – Ópera rock, música de Gleb May

Filmografía

- “Soy Cuba” (1964) – Guionista.

- “Jardín de infancia” (1984) – Director y Guionista.

- “El entierro de Stalin” (“Pójorony Stálina”), (1990) – Director y Guionista.

Premios y condecoraciones

- Orden de la Insignia de Honor, 1969 (URSS)

- Orden de la Bandera Roja del Trabajo, 1983 (URSS)

- Premio Estatal de la URSS 1984 por Mamá y la bomba de neutrones

- Orden de la Amistad de los Pueblos, 1993 (lo rechazó en señal de protesta contra la guerra en Chechenia ) (Rusia)

- Orden Leyenda Viva, 2003 (Ucrania)

- Orden de Honor, 2003 (Georgia)

- Premio Tsárskoye Seló 2003 (Rusia)

- Premio Fregene de Literatura 1981 (Italia)

- Academia SIMBA (Italia) 1984

- Premio Tizian Tabidze (Georgia)

- Premio Ianis Rainis (Letonia)

- Premio Enturia (Italia)

- Premio Triada (Italia)

- Premio Walt Whitman (EE.UU)

- Premio Aquila 2002 (Italia)

- Premio Grinzane Cavour 2005 (Italia)

- Comendador de la Orden de Bernardo O’Higgins 2009 (Chile)

- Premio Estatal de la Federación de Rusia 2009

- Premio Poeta 2013 (Rusia)

- Premio alla carriera. Festival Virgilio 2016 (Italia)

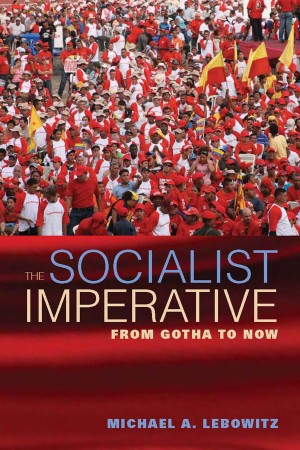

One Hundred Hours with Fidel

ONE HUNDRED HOURS WITH FIDEL

Conversations with Ignacio Ramonet, Third Edition (2006)

Below are a few selected excerpts from this 718 page book, published by the Cuban Council of State, of conversations between Cuba’s Commander-in-Chief, Fidel Castro, and Ignacio Ramonet, Editor of the French monthly, Le Monde Diplomatique. The conversations took place between 2003 and 2005. The book is dedicated to Alfredo Guevara and Ramonet’s sons, Tancrede and Axel. The book isn’t yet available in English. (July 2006)

These translations were prepared by CubaNews.

and edited by Walter Lippmann.

Chapter 10 (excerpts) and a few footnotes.

THE REVOLUTION’S FIRST STEPS AND FIRST PROBLEMS

A transition – Sectarianism – Public trials for torturers – The Revolution and the homosexuals – The Revolution and black people – The Revolution and women – The Revolution and machismo – The Revolution and the Catholic Church

In January, 1959 you did not change things overnight, but started a kind of transitional period instead, right?

We had already appointed a government. I had stated that I had no intentions to be President, a proof that I was not fighting for any personal interest. We looked for a candidate and chose a magistrate who had opposed Batista and had acquitted a number of revolutionaries.

Manuel Urrutia?

Yes, it was Urrutia. He gained prestige. It was a pity that he was a little indecisive.

Didn’t you want to be President then?

No, I was not interested. What I wanted was the Revolution, the army, the struggle. Well, if elections had been held at a given time I could have applied as a candidate, but I was not into that. My interest was focused on the revolutionary laws and the implementation of the Moncada program.

So you led the whole war without any personal ambition to be President right afterward?

Absolutely, I can assure you that. Maybe there were other reasons in addition to my lack of interest, maybe there was a little bit of pride involved, something of that; but the truth is that I was not interested. Remember that I had been presumed dead long before then. I was fighting for a Revolution and had no interest in a high position. The satisfaction of fighting, success, victory, is a much bigger prize than any position, and I was fully conscious of my words when I said I didn’t want to be President. So we gave that task to Urrutia and really respected his attributions. Both he and the 26th of July Movement appointed the Cabinet, and some of that Movement’s leaders were middle class and rather right-wing, and some others were left-wing.

There are some around who have written their memoirs, and many of them stayed with the Revolution and have said wonderful things about how they thought, about their arguments with Che and Camilo.

Did Che mistrust some of those leaders?

Che was very mistrustful and wary of some people because he had seen what had happened with the strike in April, 1958 and believed some of the 26th of July Movement leaders had had a bourgeois education. Che was very much in favor of the agrarian reform and those people were talking about a quite moderate agrarian reform and about compensations and other things. We imposed the law on them. We had that kind of problems then.

Che was not really an accommodating person. There was also anti-communism, which was strong and had its own impact. In times of McCarthyism, there were poisonous campaigns here and prejudice was fostered in many ways. And some of our people of bourgeois origins were not only anti-communist but also sectarian.

Were they far left-wing?

No, they were communists from the PSP [Partido Socialista Popular, or People’s Socialist Party], because there had been a number of Stalin-like methods and doctrines, though not in the sense that there was any abuse, but there definitely was an urge to control more and more. In that Party there was this very capable man, Anibal Escalante, who all but took over the leadership position held by Blas Roca, its historical leader and a remarkable man of very humble extraction. He was from Manzanillo, had been a shoemaker, and fought very hard. The communists fought very hard.

Blas Roca had to travel abroad, and then Anibal Escalante took over as the top leader; I’m telling you, he was skilled, intelligent, and a good organizer, but when it came to controlling things, he was a Stalinist to the core. Control is the word we’ll use for everything. He came out with a policy: “let the petit bourgeois die and let’s take care of the communists”, for he wanted to put as few communists as possible at risk. And he was obsessed about screening. He had all the old habits of a stage in the history of communism when its members had been excluded, as in a ghetto, that’s the kind of mindset he had, and he screened everyone all the time. Those methods were applied to people who were otherwise very honest and self-sacrificing.

This Anibal Escalante created a very serious problem of sectarianism. Ah, but unity prevailed! There’s a reason: I think very few political leaders would turn a cold shoulder to those horrible things. Serious mistakes of sectarianism were made. But there was no vanity, only the Revolution, the need for unity and trust. I stood up for unity under very difficult circumstances, and I still do. Anibal was not a traitor.

The Communist International and its slogans led the communists to defend unpopular issues of the Soviet Union’s policies, like the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, the occupation of a part of Poland and the war against Finland. We already talked about that. The USSR applied a policy that set up the bases for all kinds of abuse and crime… They almost destroyed the Party. Mistakes were made in Cuba due to those slogans, or rather than mistakes they led to political lines for which the Party, with its doctrine and its militants who fought and still fight for the workers’ interests, had to pay a high price. But the time came when by virtue of those pacts the Soviet communists seemed to be linked with the Nazi regime… A high price was paid for all those things which were used as an excuse for anti-communism, but as I said they were the most trustable and dedicated people.

Besides, some governments today, like those of Venezuela, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and others, are introducing progressive measures. What do you think about what Lula is doing in Brazil, for instance?

I obviously sympathize very much with the things he’s doing. He doesn’t count on the majority in the Parliament and has been forced to lean on other forces, even conservative ones, to put forward some reforms. The media have given widespread coverage to a scandal of corruption in the Parliament, but have been unable to implicate Lula, who is a popular leader. I’ve known him for many years, we have followed his itinerary, and we have talked many times. He’s a man of convictions, an intelligent, patriotic and progressive person of humble extraction who never forgets his origins nor his people, who always supported him. And I think that’s how everyone sees Lula. Because it’s not about organizing a revolution but winning a battle: eliminating hunger. He can do it. It’s about eliminating illiteracy. He can do that too. And I think we must support him.

Commander, do you think the age of revolutions and armed struggle is over in Latin America?

Look, nobody can say for sure that revolutionary changes will take place in Latin America today. But nobody can say for sure either that such changes will happen in one or several countries. It seems to me that if you make an objective analysis of the economic and social situation in some countries, you can rest assured that there’s an explosive situation. See, the infant mortality rate in the region is 65 per every thousand births, while ours is less than 6.5; that is, ten times more children die in Latin America than in Cuba, as an average. Malnutrition reaches 49% of the Latin American population; illiteracy is still rampant; tens of millions are unemployed, and there’s also the problem of the abandoned children: 30 million of them. As the President of UNICEF told me one day, if Latin America had the medical care and health levels Cuba has, the lives of 700.000 children would be spared every year… The overall situation is terrible.

If an urgent solution to those problems is not found –and neither the FTAA nor neoliberal globalization are a solution– there could be more than one revolution in some Latin American country when the U.S. least expects it. And they won’t be able to accuse anyone of promoting those revolutions.

Do you regret, for instance, having approved the entrance of the Warsaw Pact’s tanks in Prague in August, 1968 that so much surprised those who admired the Cuban Revolution?

Look, I can tell you that in our opinion –and history has proved us right– Czechoslovakia was moving toward a situation of counterrevolution, toward capitalism and the arms of imperialism. And we were against all the liberal economic reforms taking place there and in other socialist countries. Those reforms tended to increasingly strengthen market relations within the socialist society: profits, benefits, lucrative deals, material motivation, all the things that encouraged individualism and selfishness. So we understood the unpleasant need of sending troops to Czechoslovakia and never condemned the socialist countries where that decision was made.

Now, at the same time we were saying that those socialist countries had to be consistent and commit themselves to adopt the same attitude if a socialist country was threatened elsewhere in the world. On the other hand, we thought the first thing they said in Czechoslovakia was undisputable: to improve socialism. The protests about ruling methods, bureaucratic policies, and divorcing the masses were unquestionably correct. But from just slogans they moved to a truly reactionary policy. And in bitterness and pain we had to approve that military intervention.

You never knew President Kennedy personally.

No. And I think Kennedy was a very enthusiastic, clever and charismatic man who tried to do positive things. After Franklin Roosevelt, his was perhaps one of the most brilliant personalities in the U.S. He made mistakes, as when he gave green light to the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961, though it was not his operation, but Eisenhower’s and Nixon’s. He couldn’t prevent it on time. He also put up with the CIA’s activity; during his administration they designed the first plans to kill me and other international leaders. There’s no iron-clad evidence of his personal involvement, but it’s really hard to believe that someone from the CIA took the decision on his/her own of undertaking such actions without a prior acceptance by the President. Maybe he was tolerant or allowed some ambiguous words of his to be freely interpreted by the CIA.

However, despite the fact that it’s clear to me that Kennedy made mistakes –including some ethical ones– I think he was capable of rectifying and brave enough to make changes in U.S. policies. One of his mistakes was the Vietnam War. Thanks to his enthusiasm and obsessive sympathy for the “green berets” and his tendency to overestimate the power of the United States, he took the first steps to engage his country in the Vietnam War.

He made mistakes, I repeat, but he was an intelligent man, at times brilliant and brave, and I think –I have said this before– that if Kennedy had survived perhaps the relations between Cuba and the United States would have improved, since Bay of Pigs and the Missile Crisis had an impact on him. I don’t think he underestimate the Cuban people; maybe he even admired our people’s steadiness and courage.

Right on the day he was killed I was talking with a French journalist, Jean Daniel [director of Le Nouvel Observateur] who brought me a message from him saying he wanted to talk with me. So a communication was in the offing which could have perhaps helped improve our relations.

His death hurt me. He was an adversary, true, but I was very sorry that he died. It was as if I lacked something. I was hurt as well by the way they killed him, the attack, the political crime… I felt outrage, repudiation, pain, in this case for an adversary who seemed to deserve a different kind of fate.

His murder worried me too because he had enough authority in this country to impose an improvement of their relations with Cuba, as clearly demonstrated by the conversation I had with this French journalist, Jean Daniel, who was with me in the very moment when I heard the news about Kennedy’s death. pp.593-594

Do you think that under the Bush administration the United States could become an authoritarian regime?

Hardly two thirds of a century ago mankind knew the tragic experience of Nazism. Hitler had an inseparable ally –you know that– in the fear he could instill in his adversaries. By then the owner of an impressive military force, he started a war that set the world on fire. The lack of vision on the part of statesmen from the strongest European powers at the time, as well as their cowardice, gave rise to a big tragedy.

I don’t think a fascist-like regime could rise in the United States. Serious mistakes and injustices have been committed –and still exist– within its political system, but the American people count on certain institutions, traditions and educational, cultural and political values that it would be near to impossible. The risk exists at international level. The authorities and prerogatives granted to a U.S. president are such and the military, economic and technological power network of that state is so huge that, in fact, and for reasons totally beyond the American people’s control, the world is currently threatened.

HOMOSEXUALITY

One of the things the Revolution was criticized about in its first years is that it was said to display an aggressive, repressive attitude towards homosexuals, that there were camps where the homosexuals were locked away and repressed. What can you say about that?

In two words, you’re talking about a supposed persecution of homosexuals.

I have to tell you about the origins of that and where that criticism came from. I do assure you that homosexuals were neither persecuted nor sent to internment camps. But there are so many testimonies of that…

Let me tell you about the problems we had. In those first years we were forced to mobilize almost the whole nation because of the risks we were facing, which included that of an attack by the United States: the dirty war, the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Missile Crisis… Many people were sent to prison then. And we established the Mandatory Military Service. We had three problems at that time: we needed people of a certain school level to serve in the Armed Forces, people capable of handling sophisticated technology, because you could not do it if you had only reached second, third or sixth grade; you needed at least seventh, eighth or ninth grade, and a higher level later on. We had some graduates, but also had to take some men out of the universities before graduation. You can’t deal with a surface-to-air rocket battery if you don’t have a University degree.

A degree in Sciences, I assume.

You know that very well. There were hundreds of thousands of men who had an impact on many branches, not only on the preparation programs, but economic branches as well. Yet some were unskilled, and the country needed them as a result of the brain-drain we enforced in production centers. That’s a problem we had then.

Second, there were some religious groups which, out of principles or doctrines, refused to honor the flag or accept using weapons of any kind, something some people eventually used as an excuse to criticize or be hostile.

Third, there was the issue of the homosexuals. At the time, the mere idea of having women in Military Service was unthinkable… Well, I found out there was a strong rejection of homosexuals, and at the triumph of the Revolution, the stage we are speaking of, the machista element was very much present, together with widespread opposition to having homosexuals in military units.

Because of those three factors, homosexuals were not drafted at first, but then all that became a sort of irritation factor, an argument some people used to lash out at homosexuals even more.

Taking those three categories into account we founded the so-called Military Units to Support Production (UMAP) where we sent people from the said three categories: those whose educational level was insufficient; those who refused to serve out of religious convictions; or homosexual males who were physically fit. Those were the facts; that’s what happened.

So they were not internment camps?

Those units were set up all throughout the country for purposes of work, mainly to assist agriculture. That is, the homosexuals were not the only ones affected, though many of them certainly were, not all of them, just those who were called to do mandatory service in the ranks, since it was an obligation and everyone was participating.

That’s why we had that situation, and it’s true they were not internment units, nor were they punishment units; on the contrary, it was about morale, to give them a chance to work and help the country in those difficult circumstances. Besides, there were many who for religious reasons had the chance to help their homeland in another way by serving not in combat units but in work units.

Of course, as time passed by those units were eliminated. I can’t tell you now how many years they lasted, maybe six or seven years, but I can tell you for sure that there was prejudice against homosexuals.

Do you think that prejudice stemmed from machismo?

It was a cultural thing, just as it happened with women. I can tell you that the Revolution never promoted that, quite the opposite; we had to work very hard to do away with racial prejudice here. Concerning women, there was strong prejudice, as strong as in the case of homosexuals. I’m not going to come up with excuses now, for I assume my share of the responsibility. I truly had other concepts regarding that issue. I had my own opinions, and I was rather opposed and would always be opposed to any kind of abuse or discrimination, because there was a great deal of prejudice in that society. Whole families suffered for it. The homosexuals were certainly discriminated against, more so in other countries, but it happened here too, and fortunately our people, who are far more cultured and learned now, have gradually left that prejudice behind.

I must also tell you that there were –and there are– extremely outstanding personalities in the fields of culture and literature, famous names this country takes pride in, who were and still are homosexual, however they have always enjoyed a great deal of consideration and respect in Cuba. So there’s no need to look at it as if it were a general feeling. There was less prejudice against homosexuals in the most cultured and educated sectors, but that prejudice was very strong in sectors of low educational level –the illiteracy rate was around 30% those years– and among the nearly-illiterate, and even among many professionals. That was a real fact in our society.

Do you think that prejudice against homosexuals has been effectively fought?

Discrimination against homosexuals has been largely overcome. Today the people have acquired a general, rounded culture. I’m not going to say there is no machismo, but now it’s not anywhere near the way it was back then, when that culture was so strong. With the passage of years and the growth of consciousness about all of this, we have gradually overcome problems and such prejudices have declined. But believe me, it was not easy. pp.222-225

(FOOTNOTES)

4. In 1921, when the civil war ended, the Soviet Union was in ruins and its population in the grip of starvation. Lenin then decided to give up war communism and launched the New Economic Policy (NEP), a partial return to capitalism and a mixed economy, and gave priority to agriculture. The outcome was a positive one. Lenin died in 1924 and in 1928 Stalin suddenly abandoned the NEP and moved on to an entirely socialist economy, giving priority to industry in order to “construct socialism in only one country”.

5. An important theoretical discussion took place in 1963-1964 about the Cuban Revolution’s economic organization where the advocates of Economic Calculation (EC) and those of the Funding Budgetary System (FBS) opposed each other. The former, headed by Carlos Rafael Rodriguez, Alberto Mora, Marcelo Fernandez Font and the French Marxist economist Charles Bettelheim supported and defended a political project of mercantile socialism based on enterprises managed in a decentralized manner and financially independent which would compete with their respective goods and exchange money for them in the market. Material incentives would prevail in each enterprise. Planning, according to EC supporters, operates through values and markets. Such was the main road chosen and promoted by the Soviets in those years.

The latter were headed by Che Guevara and included, among others, Luis Alvarez Rom and Belgian economist Ernest Mandel, leader of the Fourth International, all of whom questioned the socialism-market matrimony. They stood for a political project where planning and market are opposing terms. Che thought that planning was much more than a mere technical asset to manage the economy. It was a way to extend the scope of human rationality while gradually decreasing the quotas of fetishism upon which faith on “economic law independence” found support.

Those who like Che preferred the Budgetary System favored the bank-based unification of all production units with a single, centralized budget, all seen as part of a great socialist enterprise (made up of each individual production unit). No purchasing-and-selling activity based upon money and marketing would take place between any two factories of a same consolidated enterprise, only exchange through a bank account registration. The goods would go from one production unit to another without ever being merchandise. Che and his followers pushed for and fostered voluntary work and moral incentive as the privileged –albeit not the only– tools to raise the workers’ socialist conscience. pp.648-649

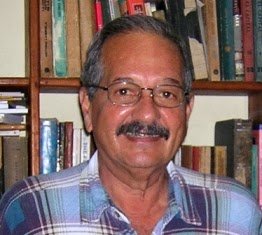

The Socialist Imperative; From Gotha to Now (2015)

THE SOCIALIST IMPERATIVE; FROM GOTHA TO NOW (2015)

by Michael A. Lebowitz [excerpts]

Monthly Review Press (2015)

pp. 135-6

Socialism: The Goal, the Paths, and the Compass

At the February 2010 Havana Book Fair, I presented my short book, El Socialismo no Cae del Cielo: Un Neuvo Comienzo, which had been published in 2009 by Ciencias Sociales (Cuba) and earlier in 2007 by Monte Avila (Venezuela). The book contained sections from Build It Now; Socialism for the 21st Century (in particular, “Socialism doesn’t fall from the sky,” well-known in Venezuela because of Chcivez’s many references to it on television and available in several free editions), and this was supplemented for Monte Avila with a new beginning, “New Wings for Socialism” from Monthly Review (April 2007). The talk provided an opportunity to introduce Cubans explicitly to the concept of “the elementary triangle of socialism,” the goal developed in “New Wings” but not named in the new book. It also was an occasion to talk about difficulties and obstacles along the path to the goal—obstacles such as those faced by Cuba then and now. Without mentioning Cuba at all, I spoke about what I had observed in Vietnam a few months earlier, and I am certain that the Cubans present understood my cautionary tale. Discovering a new path without getting lost is always challenging, and I hope that the publication by Ciencias Sociales in 2015 of the Socialists Alternative. Real Human Development, in which the argument of the socialists triangle is fully developed, will be useful.

pp. 150-151

A more recent example of the concept of democracy as consultative participation was cthe extensive discussion in Cuba over the “lineamientos,” the guidelines for the party that were circulated by the party. These were the guidelines that have set Cuba on its current path to “update” the model. Everyone was mobilized for discussions—in workplaces, neighborhoods, everywhere. The party coordinated these discussions in each separate location, and, on the basis of reports, made adjustments. For example, the great concern expressed in many meetings about the phasing out of the libreta (the set of subsidized necessities) and the release of large numbers of people from state employment led to a slowing down (although, it must be noted, not the reversal) of these decisions.

Subsequently in Cuba there were discussions of a new labor code. Here again there was extensive discussion of the document initiated by the party. As in the case of the discussions of the guidelines, this participation plays an important role in transmitting concerns from below, while at the same time educating those below as to the proposal. However, these discussions are constrained. For example, in the case of the labor code, there was no place for a general discussion of worker management. Further, there was no means for communicating from one workplace to another; rather, collective atomization characterized the process.

All of this is logical from the perspective of the conductor: he is the one who knows the score. He alone knows the whole and, therefore, activity outside this framework is to be discouraged. Further, the logic of the conductor is such that there can be only one conductor; it is, after all, essential that there be unity at the top because in its absence this would confuse the players.

There is absolutely no doubt that extensive discussions, for example, in Cuba, distinguish that society from many others. However, participation in this case is not the same as the opportunity to develop capacities through protagonistic democracy. What kinds of people are produced in this relation? Not what Marx called rich human beings. Not people who have transformed themselves through their activity and are confident in their own powers. As the Soviet Union, China, and other countries characteristic of the “real socialism” of the twentieth century demonstrated, such relations do not build the protagonistic subjects who have the strength to prevent the restoration of capitalism. The people produced within this relation are people without power.

Monthly Review Press

http://monthlyreview.org/books/pb5465/

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

You must be logged in to post a comment.