Women have to fight for life

Women have to fight for life and the Revolution alongside their male comrades.

This was the prevailing spirit of the debates at the Congress, whose sessions ended on Sunday, March 8.

By Marianela Martín and Alina Perera

March 8, 2009 00:58:49 GMT

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Vilma’s voice is being projected across the room and large screens show images of her during distinct moments of her life. In her loving tone, she speaks of the privilege of being a woman in Cuba. Like Fidel she has been a faithful promoter of our conquests.

Minutes later, young women in uniform bring Vilma’s guerilla outfit and her pistol closer to the stage, symbols that prevail during the sessions of the 8th Congress of the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC).

These were the first moments of the most important meeting of Cuban women, which ended on Sunday in Havana’s Convention Palace. The inaugural session on Saturday afternoon include the presence of the First Vice President of the Council of State and Ministers, José Ramón Machado Ventura, the Moncada Heroine, Melba Hernández, the founder of the Federation and Vilma’s comrade from the clandestine struggle and the Sierra Maestra, Asela de los Santos Tamayo, and the mothers, wives, and sons of our five compatriots unjustly imprisoned in U.S. jails for fighting terrorism.

In the meeting, where almost half of the delegates were born after 1959, the secretary general of the FMC, Yolanda Ferrer Gómez, displayed confidence in the women who will provide continuity to the life of the organization.

“Cuban women will never return to the oppressive past”, the member of the Party’s Central Committee affirmed. She repeated something that Vilma said and which Fidel has always praised: women have to put up a fight for life and the Revolution alongside their male comrades.

Especially moving was the proposal to place an image of combatant Vilma in front of the logo on the Federation’s flag. The delegates raised their hands in a sign of approval and afterwards a young woman declared that the face of this exceptional woman will be an incentive for women to become members of and take an active part in the organization’s endeavors.

Reading a summery of the Central Report to the Congress, Yolanda Ferrer emphasized that Cuban women are a «true army», in which the precepts conceived of by Vilma for the full liberation of women have taken root.

The Secretary General of the Federation acknowledged that the organization has become stronger and its membership base has grown. It has identified the most important challenges for women, developed and promoted educational and preventative programs, taken part in the tasks of the Energy Revolution, defended the incorporation of women into the work force, and decided on the modification of cardinal laws for the country, among other achievements.

“This, our first Congress of the 21st century, serves to consolidate what has been achieved” Yolanda Ferrer stated. She said that even though the FMC has advanced, it continues face challenges. The organization must improve the politics of cadres; achieve the smooth functioning and liveliness of each section of the Federation; work in a multifaceted manner in order to attend to individualities; make it so that the organization is felt in every community; energetically confront all the symptoms of corruption; and revolutionize content and ways of organizing.

During the first day, the delegates also approved the suggestion of the National Secretary to not fill the position of the President of the FMC in the future and for it remain symbolically in the hands of compañera Vilma Espín as a tribute to her.

From woman to woman.

In the morning, there were reflections by commissions dealing with cadre politics and the operation of the organization, ideological work, the formation of values, the defense of the country, international solidarity work, the participation of the women in the economy, community and preventative work, and the fight for equality and the promotion of women.

This last subject provoked multiple people to express their ideas, among which was the need to go beyond analysis that refers only to men and to women when it should be about equality.

According to the delegate’s criterion, it’s necessary to add other variables that display the principal areas where inequality is generated in Cuba today. How do the families depend on women’s economic contribution in the home? How does subjectivity function depending on the social group to which a person pertains?

Only if we see the Cuban reality as something heterogeneous and contradictory, a female member alerted, will our ways of doing politics be more effective.

Another concern expressed in the commission was in reference to the importance of respecting the diversity of preferences among human beings. This principal applied to the area of sexuality, which, according to more than one voice in the Congress, is the antidote to prejudices and discriminatory attitudes.

One woman requested that we not forget that behind each person that has sexual preferences, to which we either are or are not accustomed, there is someone who has feelings and can struggle together with us.

The director of the Cuban National Center of Sexual Education (CENESEX), Mariela Castro Espín, said in a reflection about the challenges of achieving equality that in some ways we are returning to the 1970s, when at the height of the Second Congress of the Federation, women asked for sexual orientation for their children so that they did not repeat the same errors that they had.

“We return to those problems, although with a dialectical focus – Mariela said –; gender violence is not longer as explicit; the bad keeps reducing but it does not disappear, which is why we must keep working intelligently”.

The director of CENESEX posed a question for all to ponder: How does a woman that has governmental, administrative, and political responsibilities live? With how many contradictions? “This is a problem whose solution can be found in the joint work of men and women”.

To envisage, the curative attitude of José Martí, was in the spirit of the delegates that participated in the commission, where they spoke about efforts in the community and in educational settings where it is possible to deeply confront attitudes that lessen the moral health of the nation.

Lázara Mercedes López Acea, member of the Secretariat of the Party’s Central Committee emphasized that good intentions are not enough for deploying effective preventative work: its necessary to prepare oneself. If direct attention for children and youth is important to the Federation, it’s cardinal to provide guidance to the organization’s social workers who work closely with families.

The organization’s impact in homes, in the School Councils, in its projects like the Courses of Integral Advancement for Youth, and in all of the key spaces for the education of new generations was highlighted by Lázara Mercedes. When one speaks about prevention, she said, one must always do it with infinite reserve, which the FMC has in its work with the human being.

What woman can do

In 2000, Aida Leonor Oro Lau, director of the company Inejiro Asanuma Holguin Spinning Mill, suffered an accident that caused her to lose her right hand, but did not weaken her desire to work. Now «left-handed by force», she admits, the initiatives arising from her are countless and go beyond giving orders or singing papers.

This Saturday, among delegates of the 8th Congress of the FMC analyzing the participation of women in the Cuban economy, Aida Leonor brought up the epidemic sadness that the hurricanes left in Hoguin, also known as the city of parks.

“Of my workers, 171 suffered damage to their homes and 41 were left without a place to live. The factory had to take on, amidst the chaos, the production of food for these workers and also form a strategy so that absenteeism would not affect production plans.”

With this Cuban woman in charge, operating one thread winding machine, 57,000 hours of voluntary work were done and the plans were completed.

Aida took over this company in 1992. At that time, the center suffered from shortages and the exodus of many workers. Coming from the standpoint that willpower is more powerful than the available consumables, she had the intention of diversifying products to temporarily ride it out.

With a 40 year-old sowing machine that belonged to the center and three female workers, they began to make pillows. Later the workshop grew with the obtainment of 8 of these machines and with the reclamation of the movement Sewing at Home, which the Federation promoted.

Thanks to this initiative, the factory sold 224,000 dollars worth of products at TRD stores last year, and in 2009 its sales will reach $314,000, almost 36% of which the company will pay to the state. The company envisages producing thread for textile products made in the country, including the production of antiseptic tape.

Aida spoke in the commission about replacing imports with national products and that national industry must recover its reliability. In the same discussion, Odalys Álvarez from Pinar del Rio requested that the FMC more rigorously to demand that companies pay based on results because not doing so weakens women’s incorporation in the workplace.

Audit and Control Minister Gladys Bejerano called for the creation a culture of control and prevention. She was an invited guest at the 8th Congress and spoke about the presence of women in the economic life of the country, where they have not only spread intelligent ideas but have also known how to confront corruption and other illegalities using their talent of persuasion and love.

Institutionalism and light

Institutionalism and light

By Pascual Serrano

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

If it hadn’t been for Fidel Castro’s reflection published the day after the changes announced by the Cuban government on March 2, the shake-up would have been no different, either in form or in content, than those we see all the time anywhere in the world. It was what turned the “release” of the relevant “comrades” from their “normal duties” officially notified by the Council of State, as befits its authority, into a string of serious accusations against “two of them”.

No doubt that stating and sharing personal impressions and views with the Cuban people is perfectly within the rights of whoever has been in command of their Revolution. It’s also true that, once released from his commitments as the head of the Cuban state, his words may respond exclusively to his free thoughts, as they’re no longer restrained by the moderation and diplomacy that his former post involves.

Fidel Castro himself made it quite clear on February 19, 2008 when he publicly declared his intention to not run for office again. “All I want is to fight like a soldier of ideas. It will be still another weapon we can use from the arsenal. Maybe my voice will be heard, so I must use caution”, his words were. That’s why his articles started to come out under the humble heading “Reflections by Comrade Fidel”. Some friends went so far as to compare his writings with a simple blog posted by someone who kept contributing ideas from his retired leader’s watchtower.

What complicates matters is that comrade Fidel’s reflections make headlines in the country’s two only newspapers, score more hits than any other item in all Cuban portals on line, and are read without fail on national television to the point of ousting every piece of institutional information posted by the government’s legitimate bodies.

We find, therefore, that all Cuban public institutions get subverted when it comes to communications. It had already happened when Chilean president Michelle Bachelet visited the island: a personal comment by an analyst –Fidel Castro– taking a stand in favor of Bolivia’s right to an outlet to the sea became a diplomatic issue, now twisted to the point of schizophrenia in face of the recent changes in government.

The Cuban people, Cuba’s friends, and whoever in the world follows the course of events in the country very closely noticed the gap between the government’s official statement and the ex-president’s reflection. Consequently, those of us who support Cuba find ourselves without the resources or the information we need to explain Cuban institutionalism.

We are faced with a mistake that the Cuban leaders must acknowledge and rectify. Obscurity has never been known to be a good cement to bind a people, while trust is gained by shedding light around. I would bring up the words of the great pro-independence hero José Gervasio Artigas: “With the truth I neither offend nor fear”

And Moldova lost its colors

And Moldova lost its colors

By Luis Luque Alvarez

April 16, 2009 0:19:13 CDT

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

“Color revolutions” flourished in Eastern Europe in the past few years. In Ukraine, for instance, the “Orange Revolution” managed to push Víctor Yuschenko (European Union and US favorite) to the presidency in 2005, while in Georgia, in 2003, through the «Rose Revolution» former Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Eduard Shevardnadze yielded his post vis-à-vis the momentum displayed by Mijail Shaakashvili, graduated in New York and Washington universities, and to whom the opposition now wants to give a taste of the very same medicine.

These days, another country from that same geographical area so prone to “peaceful changes” is in the headlines. It is the Republic of Moldova, a small state that was formerly a part of the Soviet Union. And it has common elements with respect to the situations developed in the above-mentioned countries: elections are staged, the opposition challenges results and incites people’s protests under the Aristotelian precept about the fact that “those who push don’t get the heat”, with the tiny presence of a foreign hand to make the «revolution» bear fruit…

It would be interesting, nevertheless, to review certain data about the country in order to better illustrate developments. Moldova is a territory of barely 33,800 square kilometers, trapped between Romania and Ukraine. At least one third of its 4.5 million inhabitants has Romanian ancestors, and the cultural influence of that nation (Romanian is the most frequently used language, for instance), to which it was united until 1940, is highly visible.

In economic terms, Moldova is considered Europe’s poorest country. The disintegration of the USSR pushed it into a deep crisis. It was only in the past few years that government actions positively operated on the population’s standards of living. Thus, if in 2001 67,8 per cent of the people were under the poverty level, this indicator was reduced to 29,1 per cent by 2006. From that year on, the conjunction of unfavorable climatic conditions (this country exports agricultural commodities, especially wine), the limitations imposed to the access to various markets and the increase in the cost of energy produced an economic decline, although President Vladimir Voronin’s administration displays a better readiness to attenuate the impact of this crisis on the more humble segments.

Another interesting element in the Moldavian case bears the name Transdnitria, a territory west of the Dniester River, inhabited mainly by Russian and Ukrainian minorities that have been fearful, since the early 1990s, of a potential annexation of Moldova to Romania, decided to disassociate themselves from Chisinau (Moldovan capital, the seat of central power) and to go their own way. After the ensuing war, a critical peace was established, because Transdnitria has not restored its links with the small country, nor has it gained any recognition from the international community as an autonomous entity, nor has a solution been found to return to Moscow a voluminous arsenal that still remains there from Soviet times.

It is obvious that, in spite of its tiny proportions, Moldova contains every necessary ingredient to become a powder keg, wedged between Ukraine (a country that longs to join NATO in spite of Russia’s opposition), Romania (a land that hosts NATO and US bases, nostalgic enough from the times when both countries were integrated, to the point of distributing Romanian passports to over 100 000 Moldovians), and, lastly, a portion of territory led by Moscow’s sympathisers, while the echo of two autonomous republics (Abjasia and Southern Ossetia, that declared their independence from Georgia and were recognized by Russia) still rings in the air.

Nevertheless, there is an ongoing peace that seems to bother certain people. How can the “revolutionary” scenarios be repeated? Thus: the opposition, dissatisfied with the new victory of the Communist Party, manages to put 5 000 people —mostly youngsters— out on the street to destroy, to request an annexation to Romania and to denounce a fraud, even if the Organization for Cooperation and Security in Europe has certified the integrity of the ballot!

And to conclude with a perfect scene of interference, comes the hand from beyond. According to President Voronin, there is evidence to prove that Romanian agents fueled the fire of demonstrations in Chisinau. That is why he expelled the Romanian ambassador, a move reciprocated by Bucharest.

But of course, there is one last trump card that is still missing. As US journalist Daniel McAdam points out on the blog LewRockwell, it was a strange sight to see so many young demonstrators armed with iPods, a modern telecommunication equipment used to summon the mob. With the low salaries paid in Moldova, these would be a luxury for any native. But putting two and two together —and here comes the trump card— we arrive at the “generosity” displayed by the US Agency for Development (USAID), that, according to its own web page, implements in this country programs to “train” “communities» in technological matters, and also in “mobilizing, pushing for change and putting demands to government”.

But days have gone by and calm has returned. The colored “revolution” did not take place, and the only thing that the Constitutional Court has ordered is not a re-run of elections, as the liberal opposition wishes, but a vote recount.

Meanwhile, some people endowed with power and influence would better, for their own health’s sake, meditate and determine if –after Kosovo, Southern Ossetia and Abjasia— it is worthwhile or not to go around throwing sparks on the Eastern European haystack…

Remembering Walterio Carbonell

Walterio Carbonell is dead

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

We could discuss at length whether something was right or wrong, or well thought-out or badly conceived, but here’s a work to be reckoned with. Those who want to use me had better know that I still feel for and act in a twofold capacity: I’m an old Cuban communist and an old French communist. Remember I joined the French [communist] party when I was studying in that country.

Walterio Carbonell (18-I-1920)

Walterio Carbonell’s major historiographic merit was that he highly valued the blacks’ contribution to Cuban culture and society as a whole social phenomenon, in keeping with Georges Gurvitch’s views on this kind of process. Until then, bourgeois historiography had either neglected or underrated black people’s participation in the national historiographic work. Among the first-class scholars, only Fernando Ortíz and Elías Entralgo had given these disregarded ethnic groups the recognition they deserved.

–Jorge Ibarra

He was an upright opponent of the Soviet flow of manuals used to start spreading Marxism and Leninism in Cuba, the reason that he had to stop teaching this subject. (…) I’m grateful to Walterio for making me understand our revolutionary process in depth and with all its complexities. Since we talked for the first time he made it plain to me in a very simple way that the solution to the problems of social, economic and racial inequality that prevail in the world today lies in socialism, as long as it’s real, democratic, participatory and free of any sign of dogmatism and intolerance.

–Tomás Fernández Robaina

Rather than a strict approach to its object of reflection, Walterio Carbonell’s book [How natural culture emerged] is one of the most singular and engrossing testimonies about the history of Cuban intelligentsia in the second half of the 20th century. It addresses the cultural debate that took place in those days from a different perspective, one way above any political quarrel, literary squabbling or intrigues to seize cultural power. Walterio Carbonell proposed a Marxist dialogue about the nation’s historical foundations, racial premises and its possibilities to keep playing its role in the Cuban Revolution’s ideological discourse. Carbonell’s book, however, went unnoticed, and with time its pages were hushed into gloomy oblivion.

–Roberto Zurbano

Walterio Carbonell, repair and homage

Walterio Carbonell, repair and homage

Author: PEDRO DE LA HOZ

pedro.hg@granma.cip.cu

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Forty-five years after the first edition, the José Martí National Library has again published Walterio Carbonell’s Cómo surgió la cultura nacional (How national culture emerged) in order to launch Ediciones Bachiller, a humble but arduous effort to rescue long-forgotten, yet essential, texts of Cuban letters.

Forty-five years after the first edition, the José Martí National Library has again published Walterio Carbonell’s Cómo surgió la cultura nacional (How national culture emerged) in order to launch Ediciones Bachiller, a humble but arduous effort to rescue long-forgotten, yet essential, texts of Cuban letters.

National Library director and renowned essayist Eliades Acosta rightly remarks that Walterio’s “is one of the most radical books of the Revolution’s historiography”. Both the author and his book were surely tagged as evil as a result of their radical nature. Going headfirst and with fully loaded cannons into historiographic conventions and domestic myths gave rise to an upheaval of wariness and denials in his epoch. What should have become a consistent discussion of his theses remained hidden in a miasma of ostracism, perhaps tampered with by the existing circumstances.

It came as no surprise to Walterio, who personally confessed to this reporter a few months ago: “my statements were racked with urgency; it was the dawn of the Revolution, our internal ideological struggle had reached its peak and I wanted to help ideological revolutionary views to gain ground. I should have reviewed what I wrote then, develop my ideas more and go deeper into more than one thing or two, but it proved impossible”.

These considerations by no means reduce the basic significance of an essay that for the first time highlighted, in an organic and integrated manner, the contribution of a dominated culture, that of black slaves, and the birth and growth of our nation.

Walterio’s starting point was a Marxist conception of history detached from any mechanistic and oppressive dogmas. When he says that, “neither the nation nor national culture are exactly its social classes, but a product”, and “the problem of creating a nation and its national culture demands an analysis that goes beyond a mere appraisal of a society’s living conditions and class conflicts”, a highly complicated issue in Cuba since, in the 19th century, “not only were the fundamental classes, to wit slaves and slaveholders, in conflict but also the psychic and cultural formation of the Spanish and African population”, the author took a decisive step towards a dialectical articulation of this topic.

He had already smashed to pieces what he called “a bookish and aristocratic approach to culture”, by wondering “whether it would be true that our cultural inventory is made up of a collection of reactionary ideas put across by Arango y Parreño, José Antonio Saco, Luz y Caballero and Domingo del Monte” or “whether by any chance popular culture, whose strength lies in black people’s traditions, is not a cultural tradition”.

In his conclusions, oddly enough, placed halfway through the text, Walterio summarizes several assessments that are full-fledged science nowadays but at that time, and so passionately expressed, they seemed inflammatory. Today, for instance, we know that “the Ten Years War is the expression of the ultimate decomposition of slavery in Cuba” and “it was waged against the metropolis as much as it was against the vast majority of slaveholders”, but I’m not sure at this juncture that ideas like “as the driving force of the colonial economy as well as the most exploited class (…) the slaves became the most revolutionary class” have been deeply studied or, instead of a response to the metropolis’s restrictive policies, “the multiple slave uprisings were a major cause of division amid the ruling class (…): annexationists and reformists”.

Walterio’s book provides the Cuban scientists with present-day proposals to debate and discuss. It would suffice to reintroduce this statement to encourage analysis: “Africa has facilitated the victory of social changes in the country, which by no means imply that Spain has disappeared. It has Africanized instead “.

At any rate, it would be both useful and convenient to breathe the fresh air supplied by Cómo surgió la cultura nacional. Walterio’s work is alive, just like he is, day after day in his quiet post there in the National Library José Martí, proud of having dedicated his book to Fidel and with the memories of having been the one who, in Paris, during the years of Batista’s tyranny, flew the 26th of July banner from the Eiffel Tower.

Norma Aleandro Turns 81

Emblematic Argentine Actress

Normal Aleandro Turns 81

May 2, 2017

A CubaNews translation by Walter Lippmann.

Icon of the Argentine cinema, actress and director Norma Aleandro arrives today at her 81st birthday in a full creative phase.

Icon of the Argentine cinema, actress and director Norma Aleandro arrives today at her 81st birthday in a full creative phase.

Much rain has fallen since she starred in The Official Story in 1985, the first film from this southern nation to win the Oscar for best foreign film and for which she earned the laurel at the Cannes Film Festival for Best Actress.

She became one of the most acclaimed faces inside and outside of Latin America, Aleandro remains very active, at once directing theater or lending her voice to classic national and world tales in a new cycle in Buenos Aires telling a story.

She recently primiered the play Escena de la vida conjugal, about the work of Swedish Ingmar Bergman, in which she directs two other great actors, Ricardo Darín and Erica Rivas, at the Maipo.

Although almost always seen in front of the cameras, the role of director also draws her.

“It’s a different place to the extent that someone else is going to take the stage but I’m in a place where being an actress is good for understanding the actor’s mind and vice versa. We are good for the actors and we also like to be able to direct, although they are two very different things,” she said in recent statements to an Argentine media.

When asked recently in an interview with the Infobae website, what is the best thing that this career has given her. She answered many things, for example she answered that many things, for example, she said, the knowledge that she can give authors telling stories.

“It helps a lot to understand the human being and therefore yourself. You have to put other people in place who have very different customs, who have loves and hatreds very different from yours, which helps you empathize with the other human being next door.

Argentines who have grown up with Aleandro thank her for her memorable movies and leave nice messages for her on social networks like Twitter and Facebook on this new birthday.

Born on May 2, 1936 in Buenos Aires, Aleandro made her debut in 1952. Among her most notable films are: Autumn Sun, Anita, Gaby: a true story, The son of the girllfriend and The Son of the Bride, and the bed inside.

(With information from Prensa Latina)

Clinical Record of the Murderer of Leon Trotsky

Clarín (Argentina)

Unpublished

Clinical Record of the Murderer of Leon Trotsky

The Cuban novelist writes about an unknown chapter of the end of Ramón Mercader in 1978.

By Leonardo Padura

A CubaNews translation. Edited by Walter Lippmann.

In Mexico. Trotsky, accompanied by Natalia Sedova, his second wife, and Frida Kahlo. (Photo: Keystone / Getty Images).

Dr. Miguel Angel Azcue, oncologist, would surely have taken many years to find out who had been the patient to whom, in the first months of 1978, he had diagnosed advanced cancer of the tonsils. In fact, it is even more probable that the doctor would never have come to know the identity of that old and sallow Spaniard who was brought to his clinic by none other than the hospital director, Dr. Zoilo Marinello.

For Dr. Azcue to find out, on October 21, 1978, who this enigmatic patient had really been (and you will understand why I use this qualifier), a whole series of coincidences, were shaped up and developed almost by a superior destiny interested in revealing to the doctor a hidden and alarming story.

The first essential fact to make the whole assemblage effective was that on October 20 Dr. Azcue saw and immediately diagnosed– the invisible assassin of Trotsky, Ramon Mercader del Río, died in Havana devoured by that cancer.

The second indispensable fact is that, against what had been arranged, news of Mercader’s death crossed the iron curtains of anonymity and silence, and, by some means, was leaked to the international press. Because –it goes without saying– the Cuban press never published this or any other news related to the presence, for four years, or the death in Cuba, of the Spaniard who, in 1940, had violently murdered the number two man of the October Revolution.

Other facts that combined to make the doctor astonished to the point of shock were that on October 21, 1978, Dr. Azcue and his colleague, Dr. Cuevas, left Havana for Buenos Aires to participate in an oncology congress to which they had been invited. If there had not been such a congress and such an invitation, Azcue and Cuevitas –as everyone calls the experienced Cuban oncologist– would not have been aboard the Aerolineas Argentinas flight that covered the Havana-Buenos Aires route at that time.

Because, if, instead of traveling with the Argentinean company, they had traveled with Cubana de Aviación, perhaps Azcue and Cuevas would not have learned the truth.

The difference lies in the newspapers that are available to the passengers in one and the other airline: On Cubana, Cuban papers; on Aerolíneas Argentinas, Argentinean press.

The Cuban newspapers, as I said before, would have contributed to keeping Azcue in ignorance for at least another day, or perhaps many more days, perhaps even forever. The Argentinean paper, on the other hand, showed him a headline which, from the start, touched him in many ways: “The Murderer of Leon Trotsky Dies in Havana” –and a photo that shook him up and down: this Ramón Mercader which appeared in the newspaper, had to be the same patient who, months ago, he and Cuevitas had diagnosed with cancer.

This was confirmed by Cuevas, his colleague from the Oncology Hospital and seat mate on the Aerolíneas Argentinas airplane it was on this plane, to almost complete the conjunctions of this history, the doctors had been given a newspaper from Buenos Aires and not one from Havana.

But, in fact, the story of Dr. Azcue’s relationship with Trotsky’s killer had begun thirty-eight years earlier in Mexico City. Azcue, who had been born in Spain, had come to Mexico very young and did not move to Cuba until about 20 years later. As a child, he heard his father say that the Soviet leader had been killed in his house in Coyoacán.

Since then, he had lived with curiosity awakened by that story that had moved not only his father –a Spanish Republican– but also millions of men and women in the world.

Over the years, he would learn the few facts everyone knew about Leon Trotsky’s killer: that his name (presumably false) was Jacques Mornard. He claimed to be a disenchanted Trotskyist, even though everyone knew it was a scam; that he had killed Trotsky with an mountain-climber’s axe, with much premeditation and tons of treachery; and that, for that crime, he served a twenty-year sentence in Mexican prisons … and practically nothing else.

Perhaps the veil of mystery, silence, plot, and deception that had gathered around the murderer had kept Azcue’s interest in that man alive over time. He kept it in Mexico, brought it to Cuba and kept it almost lost in a corner of his memory, but alive and latent.

The interest was buried in his mind when he got on the Aerolineas Argentinas plane and opened the newspaper that would place him face to face with a remarkable truth: that he, Azcue, had had this same assassin before him, had spoken to him, had touched him, and had been in charge of telling him that he would soon die.

Azcue would always vividly remember the afternoon when Dr. Zoilo Marinello brought him that patient. The fact that the director of the hospital asked him to –with his other oncologist colleagues specialized in “head and neck cancer”– examine that Spaniard who was a case “of his”, motivated Azcue’s curiosity.

Then there was also the fact that the man who –according to his words– had been seen by many doctors (he did not say who or where) who had not been able to diagnose the obvious and widespread tonsil cancer that was killing him, was a surprise to the team of specialists and marked a notch in the memory of the doctor.

Finally, the fact that the consolation treatment –a few radiation sessions that Azcue and his colleagues prescribed to the patient considering the spread of the disease– was not given to him at the Oncology Hospital, but at another institution, completed the engraving of the case in Azcue’s memory. Otherwise, perhaps he would have become one of the tens, or hundreds of people he examined every year.

In the request of the director of the hospital there were several elements that, only months later, when he knew who his patient was, did Dr. Miguel Angel Azcue begin to understand: Dr. Zoilo Marinello was an old Communist militant, brother of the politician and essayist Juan Marinello, one of the most renowned leaders of the former Popular Socialist [Communist] Party in Cuba.

As the doctor would learn much later, Ramon Mercader and his mother, Caridad del Río, had friendly relations with some of those old Cuban Communist militants, including Juan Marinello himself, and with musician Harold Gratmages with whom –Azcue would learn much, much later—Caridad had worked when Gratmages served as Cuban ambassador in Paris (1960-1964).

So, if anyone knew or had to know who the Republican Spaniard invaded by cancer was, that man was Zoilo Marinello. It was not, therefore, an ordinary request.

It was also years after Mercader’s death, and the discovery of his real identity, that Doctor Azcue would have a strange new commotion related to that dark and obscure character. It happened in the mountainous area of the center of the island: the Escambray, where there is a museum dedicated to “La Lucha contra Bandidos” (The War Against the Bandits), as the low-intensity war developed in the 1960s in that area between the guerrillas of opponents of the system and the militias and revolutionary army was called.

In that museum, among many photos, there is one of a group of fighters “cazabandidos [bandit hunters]” in which a man appears appears who … according to Azcue, had to be Ramón Mercader! Is it possible that when we all believed he was in Moscow, Mercader was in Cuba, collaborating with the Cuban anti-guerilla or counterintelligence services? Although the evidence at hand makes that possibility unlikely, Dr. Azcue believes that only if Mercader had a twin, the man in the photo at the museum (not identified in the written notes of the display) was not Mercader.

Twenty-five years after the death of Ramon Mercader, while I was beginning my research to write the novel about the assassination of Trotsky, which I named The Man Who Loved Dogs, I had the misfortune and the luck of meeting Dr. Miguel Angel Azcue. The reason was initially painful and worrisome: following the removal of a small wart that my father had on his nose, the routine biopsy done in those cases had proven positive, that is, that cancer cells were present. I immediately got in motion to see what we could do for my father and, as we always do in Cuba, the first option was to find a direct path to the possible solution: the way of friends.

Then I wrote to my old friend and study partner José Luis Ferrer, who has lived in the United States since 1989, because his mother, Dr. Maria Luisa Buch, had been the assistant director of the Oncology Hospital (under Dr. Marinello). Although she had died, surely there would remain friends on the staff of the institution. In this way, only a few days later, I arrived holding my father´s hand, at the clinic of Dr. Azcue. From the very start, he took the case as his own and –today we know: and here lies the fortunate part of the story– saved my father´s life.

It was in one of those visits to Dr. Azcue’s clinic –I had already given him some of my books and an extra-hospital friendship had developed– when I told him that I was getting ready to write a novel about Trotsky’s killer. I remember that the good doctor’s gaze locked on mine before he said, sardonically and proudly, “I met that man and I have an incredible story about him…”

* Leonardo Padura, Cuban writer. Award Princess of Asturias 2015. Author among other books of “The Man Who Loved Dogs” (Tusquets, 2009, first edition)

Leon Trotsky – EcuRed entry

Leon Trotsky

A CubaNews translation by Walter Lippmann.

Leon Trotsky

Political and Russian theorist.

First name Lev Davidovich Bronstein

Birth November 7, 1879

Yakovka Flag of Ukraine Ukraine

Death August 20, 1940

Flag of the United States of Mexico Mexico

Leon Trotsky (Lev Davidovich Bronstein) Intellectual, political and Russian theorist. He participated actively in the Russian Revolution (1917) and was organizer of the Red Army .

Biographical data

He was born in Yákovka (Ukraine) on November 7, 1879, into a Jewish family of farm laborers.

Studies

He studied in Odessa and Mykolayiv, standing out for his intellectual abilities.

He studied law at the University of Odessa.

Revolutionary activities

He began in politics in the year 1896, joining in the populist circles of Mykolayiv, although soon he joined the Marxist movement. He was a profound student of Marxist theory, to which he contributed developments such as the theory of permanent revolution.

In 1897 he founded the Workers’ League of Southern Russia, whose activities against the tsarist autocratic regime would result in his being arrested, imprisoned and sentenced to exile.

Exile

He was arrested several times and banished to Siberia. Escaped exile in 1902 and moved to Europe adopting the pseudonym of Trotsky (name of a jailer who had guarded him). During his stay abroad, he joined Vladimir Lenin, Julius. Mártov, Gueorgui Plekhanov, and other members of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP) who edited the newspaper Iskra (La Chispa).

When the second congress of the RSDLP was held in London in 1903, it was marked by differences with Lenin and the Bolsheviks and he joined the Mensheviks, without establishing strong ties.

When the Revolution of 1905 failed, he was deported back to Siberia and escaped once again in 1907 and dedicated the next decade to defend his ideas, being involved in frequent ideological disputes.

When the Russian Revolution began in February 1917, Trotsky was in New York , collaborating on a Russian newspaper, so he moved to Russia and joined the Petrograd Soviet, becoming directly involved with the Bolsheviks in the revolutionary process, becoming part of the Central Committee of the Party.

The return to Russia

After crossing several countries coming into contact with the foci of revolutionary conspirators, he moved to Russia as soon as the Revolution of February 1917, which overthrew Nicholas II, broke out.

During the first stage of the Russian Revolution, he became a trusted man of Vladimir Lenin, participating in several missions, including the negotiated withdrawal of World War I (1914-1918), through the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (1918)

He played a central role in the conquest of power by Lenin, was responsible for the taking of the Winter Palace by the Bolsheviks.

Then he became Commissar of War (1918-1925), a position from which he organized the Red Army under very difficult conditions and defeated the so-called white (counterrevolutionary) armies and their Western allies (1918-1920) in a long civil war.

Lenin was forced to withdraw from political life in May of 1922, after suffering a stroke asa consequence of an assassin’s attack. After Lenin’s death, he was removed from his position as Commissar of War in 1925 and expelled from the Political Bureau in 1926.

Exile

Stalin sent him into exile to Central Asia in 1928 and was banished from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) in 1929. He spent the rest of his life making public his criticisms of Stalin.

He lived in Turkey, France, Norway and finally in Mexico, invited by General Lázaro Cárdenas, president of the country, in 1937. He initially lived at the home of Mexican painter Diego Rivera and his wife Frida Kahlo .

Death

He was subjected to several attacks in almost all the countries and cities where he lived in exile, including the one carried out by under the orders of the Mexican communists.

Ramon Mercader, a Catalan trained by Soviet intelligence and sent from the USSR, entered the circle closest to Trotsky and carried out his. Mercader attacked Trotsky in the residence he occupied in the Mexican city of Coyoacan, on August 20, 1940 with a piolet (mountaineer’s axe), which sank in his head; But he was able to react and asked for help. Trotsky passed away the next day.

Outstanding works

He wrote numerous essays, an autobiography, My Life (1930), The History of the Russian Revolution (3 volumes, 1931-1933), The Revolution Betrayed (1936), and articles on major current issues of his time (Stalinism, Nazism, fascism or the Spanish Civil War).

His works were also highlighted:

The Permanent Revolution (1930)

Socialism in the Balkans (1910)

Literature and revolution (1924)

Results and perspectives (1906)

Contributions

He is considered by many one of the most important Marxist theorists of the twentieth century, especially in relation to the theory of revolution in the imperialist epoch: his theory of permanent revolution.

As a journalist and historian, he was recognized as one of the greatest political writers of the century. Also emphasized contributions in the field of art and culture.

External references

Biography of Leon Trotsky . Taking biographies and lives.

Phrases and thoughts

The man who loved the dogs. Leonardo Padura, 2009

The Drama of the St. Louis in Havana, May 1939

The Drama of the Liner Saint Louis in Havana (May 1939):

A Shameful Page in the History of the United States,

and Cuba as well.

By Michel Porcheron

[Translated from the French by Larry R. Oberg.Edited by Walter Lippmann and Larry R. Oberg.]

On the ground floor of the elegant art nouveau Hotel Raquel, at 103 Amargura Street in Old Havana, there is a reproduction of an original oil painting signed by the great Cuban master Victor Manuel Garcia Valdés (1877-1969).

On the ground floor of the elegant art nouveau Hotel Raquel, at 103 Amargura Street in Old Havana, there is a reproduction of an original oil painting signed by the great Cuban master Victor Manuel Garcia Valdés (1877-1969).

Long unknown and undated, it commands one’s attention from its location between the reception area and the bar. From what diaspora did this painting emerge? Everything about the painter’s existence has long remained an enigma. It is not widely known today, for example, that the original belongs to Isaac Lif, a Dominican national. To the right of the painting a short note evokes the drama of the “Saint Louis in 1939”. *

This unusual picture forms a modest part of a dramatic mosaic of universal history. It stands alongside histories, academic treatises, historical documents and novels, a Hollywood film, a documentary of unpublished archives, the log book of the commander of the Saint-Louis and multiple sites, among other bits of knowledge that document the reprehensible attitude of the United States and their then-vassal state, Cuba.

This episode, the odyssey itself and the reasons for its tragic failure, is relatively unknown and often forgotten, even today. Not by all, of course, not by those, Jewish or not, who spoke and witnessed on behalf of those who disappeared. It is this “forgetfulness”, sustained by those who had their share of responsibility for the Jewish genocide, in this case the Allied governments by their complicit inaction.

This episode, the odyssey itself and the reasons for its tragic failure, is relatively unknown and often forgotten, even today. Not by all, of course, not by those, Jewish or not, who spoke and witnessed on behalf of those who disappeared. It is this “forgetfulness”, sustained by those who had their share of responsibility for the Jewish genocide, in this case the Allied governments by their complicit inaction.

On May 13, 1939, the Saint Louis, a German liner normally assigned to the Hamburg-Amerika line, embarked for Havana with 937 German Jewish passengers. Some came directly from the concentration camps, notably Dachau and Buchenwald.

On May 13, 1939, the Saint Louis, a German liner normally assigned to the Hamburg-Amerika line, embarked for Havana with 937 German Jewish passengers. Some came directly from the concentration camps, notably Dachau and Buchenwald.

Most of the passengers had either abandoned their personal goods or had managed to sell some in order to purchase, at $150 each, landing certificates issued by the responsible person on the spot and by others who issued visas to enter Cuba. The passengers were also required to pay an additional 230 Reichsmarks in case the boat was obliged to return.

This was, in fact, a propaganda operation organized by the Nazi regime. Its aim was to demonstrate that the Jews were free to emigrate, while knowing full well that most of the host countries would deny them entry. These travellers of a special type “had to buy return tickets at a prohibitive price, even though they were not supposed to return, as well as pay for the authorization to leave Germany …” (Louis-Philippe Dalember).

This was, in fact, a propaganda operation organized by the Nazi regime. Its aim was to demonstrate that the Jews were free to emigrate, while knowing full well that most of the host countries would deny them entry. These travellers of a special type “had to buy return tickets at a prohibitive price, even though they were not supposed to return, as well as pay for the authorization to leave Germany …” (Louis-Philippe Dalember).

About half of them were women, children, and elderly men, who were setting off with the dream of rebuilding their lives on the other side of the Atlantic, far from such Nazi persecutions as Kristallnacht (Crystal Night, November 10, 1938), (1) which had demonstrated clearly the barbaric nature of the Nazi regime.

On the ship, a certain tension reigned, because in everyone’s mind it was a journey without return, still the atmosphere was quite easy-going. In the 1930s, advertising images of the Hamburg-Amerika Line shipping company presented a luxurious vision of cruises aboard its liners.

On the ship, a certain tension reigned, because in everyone’s mind it was a journey without return, still the atmosphere was quite easy-going. In the 1930s, advertising images of the Hamburg-Amerika Line shipping company presented a luxurious vision of cruises aboard its liners.

The Saint Louis had eight bridges and could accommodate 400 passengers in first class and 500 in tourist. Of course, in reality, this “cruise” was Machiavellian: It was no more than Nazi propaganda endeavoring to prove to the entire world that Hitler’s Germany did not have a monopoly on anti-Semitism.

The journey of the Saint Louis epitomizes the cowardice of some democratic states when faced with the problem of receiving Jewish refugees on the eve of the Second World War and during the Holocaust.

In 2009, a book that –apart from its great success in sales, (translation rights were ceded in a dozen languages)– had already had a resounding influence on the sometimes violent debates it provoked.

This novel, Jan Karski, written in 1942 by the author Yannick Haenel and published in France by Gallimard, documents the abandonment of the Jews of Europe by the international community, although the real witness was Jan Karski, who was Catholic, Polish and a militant in the resistance. Taken prisoner at the beginning of the war, tortured by the Gestapo, Karski managed to escape and quickly joined the Polish resistance.

A clandestine courier for his country’s government in exile, Karski, then under 30 years of age, managed to enter the Warsaw ghetto. In order to inform them of the ongoing extermination of the Jews by the Nazis, Karski was given a secret mission to London in 1942 to meet with Winston Churchill and to Washington on July 28, 1943 to meet with Franklin D. Roosevelt.

At the meeting, as described in the 1942 novel, Roosevelt yawned, pretending to be interested to better hide his passive disinterest. Karski had been listened to without being heard. In 1944, he recounted these events in his war memoir Story of a Secret State: My Report to the World, published in the United States in 1944. Yet once again no one wanted to face the facts and it was already quite late.

“What interests me in this book,” writes Yannick Haenel, “is not the Shoah, but the Western crime, the deafness of the Allies towards extermination, an organized deafness.”

Everyone at the Hamburg-Amerika Line knew that the St. Louis passengers would not land as expected. Everyone that is, except for the passengers. The commander of the Saint Louis, whose name was Gustav Schröder (a name we need to remember), was ordered to sail at 8:00 PM by the port authorities of Hamburg.

These authorities were very likely hoping to see the Saint Louis arrive at the port of Havana along with two other ships also carrying Jews: the Flanders (with 104 passengers) flying the French flag and the Orduña flying the English flag, with 154 people aboard.

In the summer of 1939, Europe was preparing for war and Adolf Hitler’s Germany was preparing for the extermination of the Jews. The departure of the Saint Louis was “highly publicized and would greatly influence world public opinion.” (Margalit Bejarano).

This tragic cruise would be adapted for the cinema. In 1976, Stuart Rosenberg, known for his 1967 film Cool Hand Luke, directed Voyage of the Damned (2). The script is based on the book by Max Morgan-Witts and Gordon Thomas.

In 1994, Maziar Bahari (3) directed Le Voyage du Saint-Louis (52 min.) for French television. The documentary includes testimonies from the rare survivors, those who tried to help them and members of the German crew.

In 1994, Maziar Bahari (3) directed Le Voyage du Saint-Louis (52 min.) for French television. The documentary includes testimonies from the rare survivors, those who tried to help them and members of the German crew.

The film, whose archival sequences, notably shot on the steamer during the Hamburg-Havana crossing, and unpublished still photographs, make it the documentary that best retraces this extraordinary odyssey.

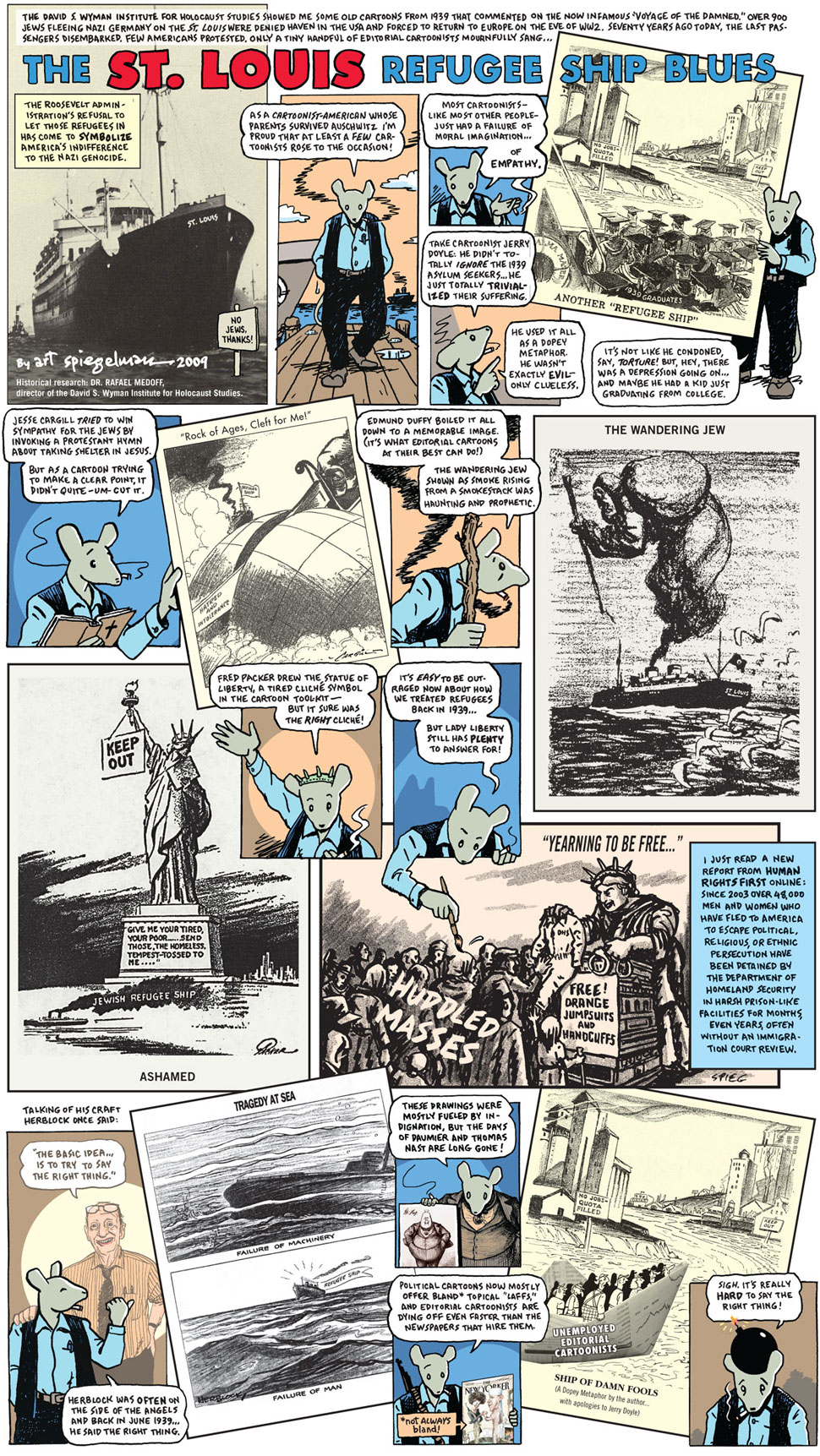

The American graphic designer, Art Spiegelman (1948), author of the famous book Maus (Pantheon Books, 1991) paid tribute in the Washington Post to the graphic designers who were among the few citizens of his country to protest the position of the American government in the Saint Louis affair. His unpublished panel from MetaMaus, a 25th anniversary Maus compendium, was published in this national daily.(4)

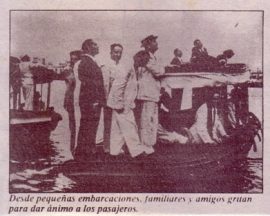

In May 1939, the Cuban Jewish community (5) awaited the arrival of the Saint Louis with great anticipation. It was an exceptional event in their lives. A German ship had never arrived carrying so many passengers. Some had family on the liner. Others knew that the refugees viewed Cuba as a first step toward arriving in the United States.

From the beginning of May 1939, the port of Havana regularly witnessed the return of Cuban fighters who had survived participation in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Various testimonies mention crossings aboard the Orduña which, it seems, made weekly crossings. A brigadista [a member of the International Brigades], from Matanzas, Julian Fernandez Garcia, reports that he “returned to Cuba, on May 27, aboard the Orduña“.

This was true as well for Juan Magraner Iglesias and Luis Rubiales Martínez, among others. Oscar Gonzalez Ancheta, had made the trip to Havana from La Rochelle, France on June 14 aboard the same boat). “We were greeted by a large crowd”, says one. “I saw loved ones waiting at the pier,” indicates another. “A large crowd came to greet us.” “

The reception was surprising. It was something that can never be forgotten. The people of Havana rushed to the Malecón where many rented small boats to greet the ship and its passengers.” (Mario Morales Mesa)

According to remarks collected by Cuban historian Alberto Bello in May 1985, Juan Magraner Iglesias recounts: “Yes, we were welcomed. The docks and the Malecon were crowded. Small boats came out to meet us. There was enormous joy. I will never forget that day.”

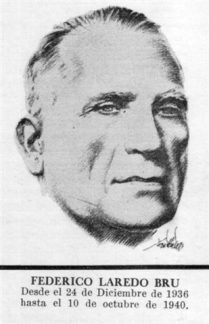

The Cuban president was a feckless Federico Laredo Bru (December 1936-October 1940). As the sixth tenant of the presidential palace since September 1933, he was unable to free the country of the effects of the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado (1925-1933). On October 10, 1940 he ceded his position to Fulgencio Batista for the latter’s first four-year term.

Cuba, while aligned with Washington’s foreign policy on the Second World War, launched in Europe in September 1939, would maintain its official position of neutrality for more than two years.

Cuba declared war on Japan, Germany and Italy on the 9th, the day after, the United States declared war against Japan (6). On the 11th, Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy declared war against the United States.

On May 23, when the Saint Louis was on its tenth day of the crossing, Captain Schröder received a telegram informing him of probable difficulties in disembarking his passengers in Havana.

Although Schröder was fully aware of what was happening in Germany, he was not pro-Nazi and he knew nothing about the Cuban events of the years 1938 and 1939. He would learn in two words that Decree 55, governing entry into Cuba … through May 5, 1939, was null and void, replaced by Decree 937, signed by President Federico Laredo Bru.

The latter had issued a decree invalidating all landing certificates. Entry to Cuba now required written authorization of the Cuban Secretaries of State and Labor and the mailing of a $500 security deposit (something not required of American tourists). On Friday, May 26, he received a second telegram (“Anchor at the anchorage, do not attempt to dock”) instructing him not to dock at the main Havana port and direct the Saint Louis towards the Triscornia administrative area.( 7).

On Saturday, May 27th, at 4:00 AM, the luxurious cruise ship Saint Louis arrived on the eastern side of Havana harbor in the Triscornia administrative area. For its passengers, hope was at its zenith.

It was not the immigration office officials who were the first to board, but rather the coastal police.

No one was allowed to disembark, apart from a few crew members. One refugee, Max Lowe, attempted suicide by slashing his veins and throwing himself overboard and was, by force of circumstance, admitted to the Calixto Garcia hospital in Havana.

For ten days, the difficulties were such that the Saint Louis –whose presence in the port had become “a real disturbance to public order”– was ordered on June 2 to leave Cuban territorial waters. Of the 937 passengers, only some 25, the only ones with proper visas upon leaving Hamburg, were allowed to land.

For ten days, the difficulties were such that the Saint Louis –whose presence in the port had become “a real disturbance to public order”– was ordered on June 2 to leave Cuban territorial waters. Of the 937 passengers, only some 25, the only ones with proper visas upon leaving Hamburg, were allowed to land.

To speed up the departure, the ship was resupplied with food, drinks and fuel. Escorted by navy patrol boats and the police, the Saint Louis moved away from the Cuban coast … Gustav Schröder took it upon himself to set the course for the United States. The boat sailed so close to Florida that passengers could see the lights of Miami. Some refugees sent a cable to President Franklin D. Roosevelt asking him to grant them asylum.

Roosevelt never responded. For three days the St Louis sailed along the coast of the United States without ever being allowed to dock. The same thing occurred in Canada where the authorities aligned themselves with U.S. and Cuban policy. In fact, they were aligning themselves with the policy of Cordell Hull, Secretary of State in the Roosevelt government: the pretext being that immigrant quotas had been filled.

“Roosevelt was clearly absent, as was the Canadian Prime Minister, Mackenzie King, who privately declared that he did not care to have too many Jews in his neighborhood” (Christophe Alix) … On June 6, short of food and only 25 days after its departure from Hamburg, the Saint Louis, with its human cargo, had no alternative but to cross the Atlantic in the other direction toward Europe. But where to? Gustav Schröder sailed the Saint Louis at low speed, as if he were waiting for a last-minute solution in the open seas.

On March 11, 1993, Captain Gustav Schröder was posthumously recognized as Righteous. Later, Jan Karski, who died in 2000, would be granted the same recognition.

The behavior of German Captain Schröder during the course of the voyage surprised the passengers from the start. Despite the presence on board of a small number of Nazi agents, including Otto Shiendick of the Gestapo, he insured that “the journey take place as if it were a normal cruise and that the refugees be treated with the utmost respect.” The 14 days of travel therefore were joyous and festive (Louis-Philippe Dalembert), with benefits well beyond those routinely offered by the liner and the expectations of the asylum seekers.

===

According to Dalembert (LPD) on May 23, Schroeder assembled a number of passengers, lawyers and others with a special knowledge of law, in an effort to resolve their difficulties. “In his soul and conscience he knew that he would do everything possible to help these people find a host country” (LPD).

In Triscornia, he would not oppose those who were observant from using a corner of the Saint Louis as an improvised synagogue. Obliged to return to Europe, Captain Schröder seriously considered scuttling his ship along the British coast, an action that would make it impossible for his passengers to be returned to Germany.

Schröder died in 1959. On March 11, 1993, he was posthumously awarded the Righteous Among the Nations medal by the state of Israel. As early as May 13, 1939, he had kept a personal logbook. Heimatlos auf hoher See (The St Louis Epoch), Berlin: Beckerdruck, 1949.

What happened in Havana between May 27 and June 2? Why were more than 900 German Jewish refugees turned away? Above all, it was because the government of Laredo Bru always obsequiously obeyed Washington’s directives. Internal events also had an obvious affect:

What happened in Havana between May 27 and June 2? Why were more than 900 German Jewish refugees turned away? Above all, it was because the government of Laredo Bru always obsequiously obeyed Washington’s directives. Internal events also had an obvious affect:

First of all, since November 8, 1933, the “Ramon Grau” law required employers to employ at least 50 percent native Cubans. The slogan of the first Presidency (Grau San Martin, September 1933 – January 1934) “Cuba para los cubanos” [Cuba for the Cubans] was not directed against the Jews as such, but against all foreign populations.

Moreover, and even more seriously, a xenophobic and anti-Semitic atmosphere had been a reality since 1933, even though it was not officially encouraged by the government (no Cuban government of the period would have had an openly anti-Semitic policy, and the vast majority of the population was not anti-Semitic.)

The first anti-Semitic public demonstrations appeared in the last months of the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado, whose colleague, German dictator Hitler, had been in power since January 30, 1933. In Germany, as early as July 1932, the Nazi party had won a majority in the Reichstag. Hermann Goering became president. Hitler’s Mein Kampf had been published in 1925. Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda ministry was fully operational from its inception in March of 1933. The first anti-Jewish measures date from July 1933, but anti-Jewish propaganda had begun even earlier.

The first anti-Semitic public demonstrations appeared in the last months of the dictatorship of Gerardo Machado, whose colleague, German dictator Hitler, had been in power since January 30, 1933. In Germany, as early as July 1932, the Nazi party had won a majority in the Reichstag. Hermann Goering became president. Hitler’s Mein Kampf had been published in 1925. Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda ministry was fully operational from its inception in March of 1933. The first anti-Jewish measures date from July 1933, but anti-Jewish propaganda had begun even earlier.

In Cuba, information about Nazi persecution of European Jews arrived regularly. National-Socialist propaganda as well. It found fertile ground among the wealthy and less wealthy Spanish traders, who viewed the arrival of new Jewish immigrants with a jaundiced eye. Some even supplied arms to Nazi “delegates” in the Cuban capital.

The mouthpiece of these members of the Spanish community was the newspaper El Diario de la Marina published by José Ignacio (Pepin) Rivero, whose family also published two other newspapers, Avance and Alerta. Anti-Jewish actions intensified at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936. The Spanish Falange in Cuba and the Nazi agents made common cause in denouncing the “Jewish danger” in the name of safeguarding the Spanish race.

In 1938, the Partido Nazi Cubano was created by a certain Juan Prohias. It had its headquarters at 406, 10th street (between 17th and 19th streets) in the central district of Vedado. Every day on his radio show, Hora Liberal Independiente, Prohias attacked the Jews and their immigration into Cuba.

He was given a personal address on Flores Street, between Enamorados and Santo Suarez. Although the authorities did not display official anti-Semitism, they never bothered the fascist or Nazi groups and did not seek to neutralize or prohibit them. El Diario de la Marina, the daily newspaper of the Francoists, had always been published without interference. It had never been banned.

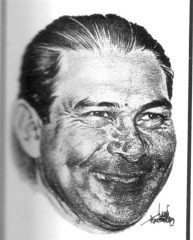

Fulgencio Batista

On Cuban territory, the network of Nazi agents was composed of some 60 members. The newspapers of the Rivero group had called for a demonstration to protest against the arrival of “foreign Jews” aboard the Saint Louis.

The xenophobic and anti-Semitic atmosphere was further fueled by Primitivo Rodriguez Rodriguez, who was part of the militant wing of the Partido Auténtico, the party of former President Ramon Grau. According to Grau, the Cuban people had a duty to “fight against the Jews until the last of them had been driven out” (L.P.D).

Paradoxically, a certain Louis Clasing, Hamburg-Amerika’s director in Havana, was part of this movement as well. He immediately financed the campaign to reject the Jewish refugees who, ironically, had been transported to Cuba by his own company. Thus, this Nazi agent was responsible for demonstrating that Jews were undesirable everywhere, not only in Germany.

The Jewish community did not remain inactive, having years before successively created the Centro Intersocial Hebreo de Cuba; the Jewish Committee for Cuba; the Central Committee of the Sociedades Hebreas de Cuba; the Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS); and JOINT (the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee). But these societies were more like community self-help and defense organizations than militant movements in the life of Cuban civil and political society.

Some Jews owned flourishing shops. Many were tailors, furriers and shoemakers. They were also active editorially and some were magazine publishers. A number of Jews were militants in progressive organizations.

One of them, Fabio Grobart, was one of the 13 founders of the Cuban Communist Party (August 1925), along with three other “polacos” (Polish, Poles), Gurwich, Grinberg and Wasermann. Among the Jewish refugees living in Cuba, Moisés Raigorodsky Suria was one of those who joined the Spanish Republicans between 1936 and 1939.

If the mission of the Saint Louis failed, it was partly due to the political context created by the new Decree 937. In other words, internal struggles for power. Those involved included the puppet president Laredo Bru, the Director General of the Immigration Bureau, Manuel Benitez Gonzalez; the man of the “landing permits”; and of course, the “strong man of power”, the head of the army, former sergeant Fulgencio Batista; as well as Lawrence Berenson, New York lawyer for JOINT (the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee) in the USA and Batista’s business lawyer.

If the mission of the Saint Louis failed, it was partly due to the political context created by the new Decree 937. In other words, internal struggles for power. Those involved included the puppet president Laredo Bru, the Director General of the Immigration Bureau, Manuel Benitez Gonzalez; the man of the “landing permits”; and of course, the “strong man of power”, the head of the army, former sergeant Fulgencio Batista; as well as Lawrence Berenson, New York lawyer for JOINT (the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee) in the USA and Batista’s business lawyer.

The latter did not wish to know anything and made no gesture. It was the eve of the presidential election campaign and Batista did not wish to take any risks, especially not with regard to Washington. He would succeed Laredo Bru for his first term as president. In order to get rid of Manuel Benitez, Laredo Bru opened an investigation, charging him with “repeated corruption.”(8). Thus, Benitez was going to pay for all the others, including his old friends and bosses.

For several days, in addition to attempts to negotiate between special envoy Berenson and the emissaries of Laredo Bru, the event gave evoked lively public interest. Friends and relatives, some from the United States, as well as newcomers, could approach the Saint Louis aboard small craft and communicate with passengers by signaling or shouting.

The press as a whole followed the unfolding of the affair and in town everyone shared the latest developments in the saga of the Saint Louis. Messages of solidarity with the passengers arrived from different countries, often demanding the intervention of President Roosevelt. “During the entire week, the drama surrounding the ship was the focus of public interest.” (Margalit Bejarano).

Of the 120 Austrian, Czech and German Jews who were, on May 27, 1939, aboard the Orduña, only 48 were able to land, despite the fact that their papers were not in order. With the other 72 refugees, the Orduña headed for South America.

After crossing the Panama Canal, it made brief stops in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, where only four refugees were allowed to disembark. The other 68 were transferred to another English ship which was going back toward the Panama Canal. Seven of the 68 obtained visas for Chile while in Balbao. The last 61 were interned at Fort Amador in the Canal Zone where they remained until they were admitted to the USA in 1940.

As for the 104 Jews on the Flanders, none were allowed to land. The French boat headed toward Mexico, but without success. It then headed back to France, where the French authorities placed its passengers in an internment camp.

One can imagine what followed. In Europe, 200 Jews embarked on another ship, the Orinoco, originally due to arrive in Havana in June of 1939. After the events of May, however, this trip was canceled. No one was allowed to land and all 200 ended up returning to Germany, where their fate was marked out for them.

After the outbreak of the World War, the arrival in 1942 of two other boats, the Sao Tomé, from Lisbon and Casablanca, and the Guinea, marked the temporary end of refugee immigration. Four hundred and fifty passengers had been able to land, thanks to the intervention of countries of the Allied Forces.

But they had to spend eight months in the Triscornia administrative area and were not allowed to stay on the island itself. Margalit Bejarano says that it was from the testimonies she had collected that the history of the Sao Tomé appears for the first time.

A week after the Saint Louis had left Havana, the only contacts that Gustav Schröder had were those with SEAL in Europe. Four countries had agreed to receive the liner’s refugees, France (224), Holland (181), Belgium (214) and England (287). It was on June 10th that Schröder learned by telegram that he could land in Belgium.

The Saint Louis finally reached the port of Antwerp. In September 1939, the war broke out. More than 680 refugees from France, Belgium and Holland would be among the deportees and most would perish in Auschwitz and other concentration camps. Less than a third of the passengers – those who were able to land in England – survived the Holocaust.

The Saint Louis was heavily damaged by fire that occurred during the allied bombings of Kiel on August 30, 1944. It was, nonetheless, repaired and served as a hotel boat in Hamburg from 1946 until 1952 when it was sent to Bremerhaven to be scrapped.

Gerge Blachmann in 1923

“Irony of History. Some passengers, like the Blachmanns, the Reifs and the Gottfriedes later succeeded in settling in the USA where they re-started their lives.”(LPD)

Notes:

* – The reproduction, also on canvas, is picture perfect and shares the exact dimensions of the original (Diáspora, oil on canvas, 94 x 96.8 cm). According to the testimonies of the first owner, a collector and close acquaintance of the painter, the theme of the painting, actually titled Los Olvidados [The Forgotten], could be identified and an imprecise date, the 1940s, tentatively advanced. However, as Ramon Vazquez Diaz, a specialist in Cuban art, writes: “We do not know the precise circumstances and motivations that led to this oil, which has never been taken out of private collections. Personal impulse or fulfillment of an order?” Http://www.vanguardiacubana.com/articulos/Victor-Manuel-homenaje-comunidad-hebrea.htm [image unavailable 2017]]

In the picture, the protagonists, women and children, are shown to be ashore rather than on the ship, which is contrary to the facts.

Victor Manuel Garcia (cf. p.374, Catalog of the exhibition “Cuba Art and History, from 1868 to the present day“, Museum of Fine Arts of Montreal, 2008): He presented his first personal exhibition in 1924. In 1925, he visited Europe for the first time.

On his return to Cuba in 1927, he presented a personal exhibition and participated in the Art Nouveau Exhibition, an event that marked the emergence of modern painting in Cuba. Since then, he has been considered one of the principal reformers of Cuban art, not only for his own work, but also for the influence he exerted among young artists.

In 1929, he left for Europe, traveling to Spain and Belgium and settling in France. It was in Paris that he painted La Gitana tropical [The Tropical Gypsy], a work emblematic of all his paintings. He exploited two major themes he never abandoned: the female portrait and the Cuban landscape.

His works were awarded prizes at the National Salon of Painting and Sculpture in 1935 and 1938. At the 1959 annual exhibition, in tribute to him, he was awarded a retrospective exhibit. (Roberto Cobas).

(1) – Kristallnacht [Crystal Night] (November 9-10, 1938), orchestrated by Goebbels, ended with 7,500 Jewish shops being looted, hundreds of synagogues burned and 30,000 Jews arrested. To escape these abuses, more and more Jews left Germany while there was still time.

Beginning in October 1941, all Jewish emigration would be prohibited. In Europe, Jews would find refuge mostly in Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, France and Switzerland. In the Americas, the largest number took refuge in the United States and, to a lesser extent, in Argentina. Finally, some tried their luck in China. But many would ultimately be caught up in the war.

As early as 1933, Hitler began imposing racist theories on Germany. He started by enacting a series of discriminatory measures. On April 7th non-Aryans were banned from civil service. In September 1935, the Nuremberg laws prohibited mixed marriages and deprived German Jews of their civil rights and citizenship. Violence increased over the following months.

(2) – The film, directed by Stuart Rosenberg (1928), while recounting the story, unfortunately makes use of some of Hollywood’s most melodramatic clichés. The commercialization of the film and the parade of stars playing sketchily drawn characters, discredited it. However, few films have had such a brilliant cast: Faye Dunaway, Max von Sydow, Oskar Werner, Malcolm McDowell, Orson Welles, James Mason, Lee Grant, Ben Gazzara, Katharine Ross, Luther Adler, Paul Koslo, Michael Constantine, Nehemiah Persoff, Jose Ferrer, Fernando Rey, Maria Schell, Helmut Griem, Julie Harris, Sam Wanamaker, Denholm Elliott. Although the film was a British production, it proves that Hollywood is capable of anything. Lee Grant was nominated as best supporting actress for an Oscar in 1977. The film was also rewarded with numerous other nominations.

(2) – The film, directed by Stuart Rosenberg (1928), while recounting the story, unfortunately makes use of some of Hollywood’s most melodramatic clichés. The commercialization of the film and the parade of stars playing sketchily drawn characters, discredited it. However, few films have had such a brilliant cast: Faye Dunaway, Max von Sydow, Oskar Werner, Malcolm McDowell, Orson Welles, James Mason, Lee Grant, Ben Gazzara, Katharine Ross, Luther Adler, Paul Koslo, Michael Constantine, Nehemiah Persoff, Jose Ferrer, Fernando Rey, Maria Schell, Helmut Griem, Julie Harris, Sam Wanamaker, Denholm Elliott. Although the film was a British production, it proves that Hollywood is capable of anything. Lee Grant was nominated as best supporting actress for an Oscar in 1977. The film was also rewarded with numerous other nominations.

This film, Hubert Niogret wrote in Positif, is “superficial, and ultimately dishonest despite its good intentions, since it actually obscures the historical drama behind a two-penny soap opera script.” The music of Lalo Schifrin saves nothing.

3) – Captain Schröder, who is credited as a co-writer was most probably the only person to have contributed material, in his case his logbook, to the script. In terms of casting, we find Manuel Benitez Jr (In Miami) Manuel Benítez, Laredo Bru and passengers, Philip Freund, Karl Glesman, Don Haig, CD Howe, Herbert Karliner, William Lyon Mackenzie King, Sol Messinger, Harry Rosenbach. Marx, Liesl Loeb, Jane Ripotot, Susan Schleger, Muriel Edelstein, Susan Shanks.

3) – Captain Schröder, who is credited as a co-writer was most probably the only person to have contributed material, in his case his logbook, to the script. In terms of casting, we find Manuel Benitez Jr (In Miami) Manuel Benítez, Laredo Bru and passengers, Philip Freund, Karl Glesman, Don Haig, CD Howe, Herbert Karliner, William Lyon Mackenzie King, Sol Messinger, Harry Rosenbach. Marx, Liesl Loeb, Jane Ripotot, Susan Schleger, Muriel Edelstein, Susan Shanks.

(4) – The St Louis Refugee Ship Blues by Art Spiegelman.

“Few Americans protested, only a tiny handful of editorial cartoonists mournfully sang… The St. Louis Refugee Ship Blues.“ (Art Spiegelman.) He had found these drawings in the archives of the David S.Wyman Institute for Shoah Studies. In Maus, a graphic novel (1972, published in book form from 1986 on), Art Spiegelman poignantly recounts how his father survived the Holocaust.

Few cartoons, immediately upon their publication, have been considered major cultural events. This, however, was the case with Maus, (mouse in German) an autobiography in the form of an animal cartoon. In the United States, perhaps even more so than in Europe, comic strips were considered mere entertainment. To its credit Maus made many American intellectuals aware that this mode of expression is not inherently insignificant.

(5) – In popular usage in Cuba, a Jew was often called a “Polaco” (Pole, Polish). “Just as the Spaniards here are called ‘gallegos’, all Jews, regardless of the country from which they came, were ‘polacos’. Polaco was part of the landscape.” (Ciro Bianchi, 2008).

(5) – In popular usage in Cuba, a Jew was often called a “Polaco” (Pole, Polish). “Just as the Spaniards here are called ‘gallegos’, all Jews, regardless of the country from which they came, were ‘polacos’. Polaco was part of the landscape.” (Ciro Bianchi, 2008).