Walterio Carbonell, repair and homage

Author: PEDRO DE LA HOZ

pedro.hg@granma.cip.cu

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Forty-five years after the first edition, the José Martí National Library has again published Walterio Carbonell’s Cómo surgió la cultura nacional (How national culture emerged) in order to launch Ediciones Bachiller, a humble but arduous effort to rescue long-forgotten, yet essential, texts of Cuban letters.

Forty-five years after the first edition, the José Martí National Library has again published Walterio Carbonell’s Cómo surgió la cultura nacional (How national culture emerged) in order to launch Ediciones Bachiller, a humble but arduous effort to rescue long-forgotten, yet essential, texts of Cuban letters.

National Library director and renowned essayist Eliades Acosta rightly remarks that Walterio’s “is one of the most radical books of the Revolution’s historiography”. Both the author and his book were surely tagged as evil as a result of their radical nature. Going headfirst and with fully loaded cannons into historiographic conventions and domestic myths gave rise to an upheaval of wariness and denials in his epoch. What should have become a consistent discussion of his theses remained hidden in a miasma of ostracism, perhaps tampered with by the existing circumstances.

It came as no surprise to Walterio, who personally confessed to this reporter a few months ago: “my statements were racked with urgency; it was the dawn of the Revolution, our internal ideological struggle had reached its peak and I wanted to help ideological revolutionary views to gain ground. I should have reviewed what I wrote then, develop my ideas more and go deeper into more than one thing or two, but it proved impossible”.

These considerations by no means reduce the basic significance of an essay that for the first time highlighted, in an organic and integrated manner, the contribution of a dominated culture, that of black slaves, and the birth and growth of our nation.

Walterio’s starting point was a Marxist conception of history detached from any mechanistic and oppressive dogmas. When he says that, “neither the nation nor national culture are exactly its social classes, but a product”, and “the problem of creating a nation and its national culture demands an analysis that goes beyond a mere appraisal of a society’s living conditions and class conflicts”, a highly complicated issue in Cuba since, in the 19th century, “not only were the fundamental classes, to wit slaves and slaveholders, in conflict but also the psychic and cultural formation of the Spanish and African population”, the author took a decisive step towards a dialectical articulation of this topic.

He had already smashed to pieces what he called “a bookish and aristocratic approach to culture”, by wondering “whether it would be true that our cultural inventory is made up of a collection of reactionary ideas put across by Arango y Parreño, José Antonio Saco, Luz y Caballero and Domingo del Monte” or “whether by any chance popular culture, whose strength lies in black people’s traditions, is not a cultural tradition”.

In his conclusions, oddly enough, placed halfway through the text, Walterio summarizes several assessments that are full-fledged science nowadays but at that time, and so passionately expressed, they seemed inflammatory. Today, for instance, we know that “the Ten Years War is the expression of the ultimate decomposition of slavery in Cuba” and “it was waged against the metropolis as much as it was against the vast majority of slaveholders”, but I’m not sure at this juncture that ideas like “as the driving force of the colonial economy as well as the most exploited class (…) the slaves became the most revolutionary class” have been deeply studied or, instead of a response to the metropolis’s restrictive policies, “the multiple slave uprisings were a major cause of division amid the ruling class (…): annexationists and reformists”.

Walterio’s book provides the Cuban scientists with present-day proposals to debate and discuss. It would suffice to reintroduce this statement to encourage analysis: “Africa has facilitated the victory of social changes in the country, which by no means imply that Spain has disappeared. It has Africanized instead “.

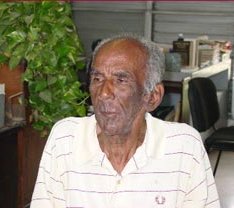

At any rate, it would be both useful and convenient to breathe the fresh air supplied by Cómo surgió la cultura nacional. Walterio’s work is alive, just like he is, day after day in his quiet post there in the National Library José Martí, proud of having dedicated his book to Fidel and with the memories of having been the one who, in Paris, during the years of Batista’s tyranny, flew the 26th of July banner from the Eiffel Tower.

You must be logged in to post a comment.