Literature 2

Leonardo Padura’s Havana Tetrology

Havana Tetrology, or, the Urgent Need to Read Padura

As part of the 29th edition of the Book Fair, Cuban writer Leonardo Padura’s Past Perfect and Winds of Lent were presented. Afterwards, Ediciones Unión will publish a second volume with Máscaras y Paisaje de otoño

Published: Friday 14 February 2020 | 12:36:15 pm.

By Dailene Dovale de la Cruz digital@juventudrebelde.cu

By Dailene Dovale de la Cruz digital@juventudrebelde.cu

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

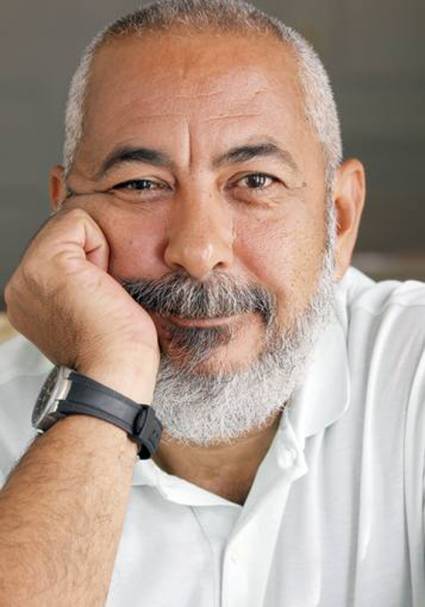

Cuban writer Leonardo Padura. Author: RTVE Published: 21/09/2017 | 06:11 pm

I woke up today with a book in my hands. I read it when I wake up, while I have breakfast, in the bathroom, before getting dressed, when I walk, inside the bus -sweaty and stress- in the Faculty… I lined it with an old magazine to take care of it among so many adventures. He’s my first literary love at this Book Fair.

It was Sunday, February 9, 2020. I had arrived at the entrance of Morro Cabaña. A friend of mine – curly hair, a skinny, ungainly body – greeted me. That day they were presenting Padura’s book, and I suddenly found a direction for my absent-minded steps.

The Alejo Carpentier room received passionate readers, who arrived hours before the meeting, sat down, lined up in a very long queue to buy the book, waited, got excited. Leonardo Padura presented the first two parts of Tetralogía de La Habana: Pasado Perfecto and Vientos de Cuaresma. Later, Ediciones Unión will publish a second volume with Masks and Autumn Landscape.

What is the Count up to, people ask him in the street. Your Mario Conde has transcended printed paper and is no longer yours, or perhaps he never was at all. For Francisco López Sacha this is the Cuban character of the 20th century, just as Cecilia Valdés was in the 19th century.

Leonardo Padura looked confident, proud of his work and of Conde in particular. The afternoon passed peacefully. And the space, small and warm, was full but in total silence. They listened.

Padura spoke of his need to narrate so as not to go crazy in the early 1990s and how his favorite reader is the Cuban public, the one he thinks about while writing in his native Mantilla.

After the immense queue, of passing and paying – “one book per person”-, of receiving with emotion the dedication, the individual is left in front of the work. Why do so many people follow and adore Mario Conde and Padura? That could be the first classic question.

Padura’s novels burst onto the literary scene, to change some fixed judgments especially regarding the crime novel. They are very Cuban novels, in the author’s own words, without imitating some somewhat predictable patterns that characterized part of the detective novel published in the country during the 1970s (with its exceptions).

See here this Timeline (Scroll down for slide show)

http://www.juventudrebelde.cu/cultura/2020-02-14/tetralogia-de-la-habana-o-la-necesidad-imperiosa-de-leer-a-padura

In Past Perfect, for example, the “hero” accumulates defects, vices, incurs a compartment that we could call immoral or that borders on such classification. Nevertheless, it is he who gets up to work – even after a drunken, haggard and exhausted bout. It is he who feels and loves his city, with all its defects… On the obverse side, there are the unpolluted, perfect and false. On them, after the typical characterization (an impeccable man), little dirty rags begin to fall (which in the end are a whole dump).

These novels are social criticism, still valid and necessary. The kind of book that catches you on a Sunday afternoon, and accompanies you during your breakfast/lunchtime meals, when you wake up or after you go to sleep. All that remains is to invite you to let yourself be caught. Conde, a little bit disheveled, will teach you the well-known phrase about deceptive appearances and will make you reflect a little bit on Cuba, Havana and how each one assumes and builds life, in the middle of their circumstances.

Charles Dickens, orThe Adventure of Reading

Charles Dickens, or The Adventure of Reading

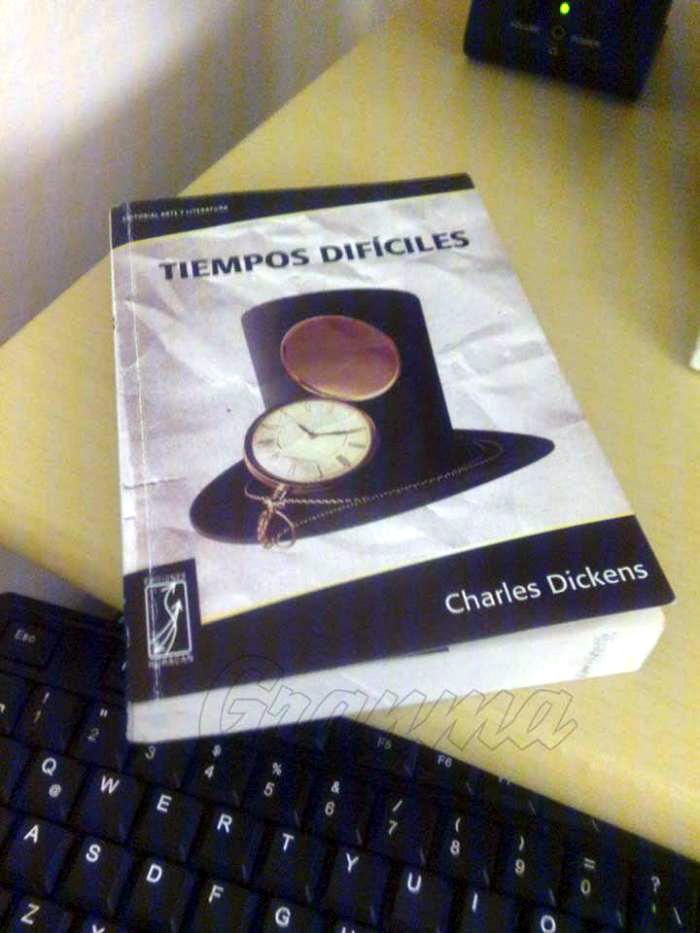

It doesn’t matter that Charles Dickens (1812-1870) died so long ago, what he wrote is still alive for anyone who wants to assume the adventure of reading, and during these months the bookstores of the country stimulate the encounter with the English novelist, through difficult times (Editorial Arte y Literatura, Colección Huracán, 2017).

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Every summer, inevitably, I associate the season with reading. Since my student days, I’ve been looking forward to those months when, in addition to taking a walk, going to the beach, watching movies or series, reading as much as I wanted and as much as I wanted, without academic demands.

Now, professional life leaves less leisure time, but I still can not conceive of a vacation, not even an obligatory medical rest, without reading some postponed titles. If the book comes in through one door, boredom comes out through the other.

Where literature reigns, the overwhelming and sticky Cuban heat can give rise to the icy feeling of helplessness on a 19th-century English street, with hands terrified by the cold and eyes tarnished by thick factory smoke.

It doesn’t matter that Charles Dickens (1812-1870) died so long ago, what he wrote is still alive for anyone who wants to take on the adventure of reading, and during these months the country’s bookstores stimulate the encounter with the English novelist through difficult times (Editorial Arte y Literatura, Colección Huracán, 2017).

Assuming today those classics where the author does not hesitate to show his “hairy ear” and interrupts the plot to give assessments and question the reader himself, can be a somewhat “strange” experience for those accustomed to contemporary works.

However, there is a singular pleasure in feeling as close to women or men as Dickens, capable of writing more than 400 pages of intelligent and nuanced stories without computers.

In Hard Times (1854) rationality and feeling are confronted; there are no archetypes of good and bad, and few characters are spared the irony with which the author describes a social panorama where money was the center, and the craziest theories were invented -perhaps the great-great-grandparents of fake news- to justify that some had everything and others nothing.

As a good narrator, Dickens avoids clichés and suspicious happy endings, although some crooked beings receive some divine justice and others redemption. It takes advantage of its pages for a defense that is not at all working class pamphletarian, relegated to being born and dying confined to the same spaces, and without even expectations.

Thus, the worker Stephen Blackpool makes a perhaps naive, though accurate, defense of his own: “I do not know how it happens, madam, that the best qualities we have are precisely those that lead us to almost all our difficulties, misfortunes and errors. (…). We are also suffering people and, as a general rule, we want to do well. I can’t think that all the faults are on our side.

Hard Times is a crusade against hypocrisies, which the author mocks mercilessly, and also a powerful reflection on the most despicable human qualities and those essential – among them imagination – to try happiness.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

You must be logged in to post a comment.