Charles Dickens, or The Adventure of Reading

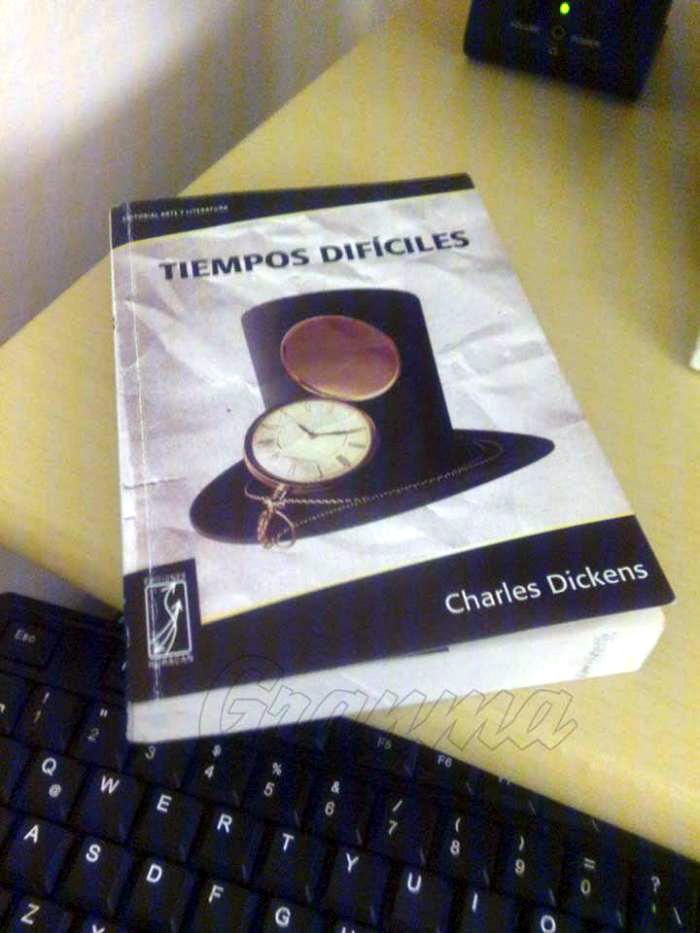

It doesn’t matter that Charles Dickens (1812-1870) died so long ago, what he wrote is still alive for anyone who wants to assume the adventure of reading, and during these months the bookstores of the country stimulate the encounter with the English novelist, through difficult times (Editorial Arte y Literatura, Colección Huracán, 2017).

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Every summer, inevitably, I associate the season with reading. Since my student days, I’ve been looking forward to those months when, in addition to taking a walk, going to the beach, watching movies or series, reading as much as I wanted and as much as I wanted, without academic demands.

Now, professional life leaves less leisure time, but I still can not conceive of a vacation, not even an obligatory medical rest, without reading some postponed titles. If the book comes in through one door, boredom comes out through the other.

Where literature reigns, the overwhelming and sticky Cuban heat can give rise to the icy feeling of helplessness on a 19th-century English street, with hands terrified by the cold and eyes tarnished by thick factory smoke.

It doesn’t matter that Charles Dickens (1812-1870) died so long ago, what he wrote is still alive for anyone who wants to take on the adventure of reading, and during these months the country’s bookstores stimulate the encounter with the English novelist through difficult times (Editorial Arte y Literatura, Colección Huracán, 2017).

Assuming today those classics where the author does not hesitate to show his “hairy ear” and interrupts the plot to give assessments and question the reader himself, can be a somewhat “strange” experience for those accustomed to contemporary works.

However, there is a singular pleasure in feeling as close to women or men as Dickens, capable of writing more than 400 pages of intelligent and nuanced stories without computers.

In Hard Times (1854) rationality and feeling are confronted; there are no archetypes of good and bad, and few characters are spared the irony with which the author describes a social panorama where money was the center, and the craziest theories were invented -perhaps the great-great-grandparents of fake news- to justify that some had everything and others nothing.

As a good narrator, Dickens avoids clichés and suspicious happy endings, although some crooked beings receive some divine justice and others redemption. It takes advantage of its pages for a defense that is not at all working class pamphletarian, relegated to being born and dying confined to the same spaces, and without even expectations.

Thus, the worker Stephen Blackpool makes a perhaps naive, though accurate, defense of his own: “I do not know how it happens, madam, that the best qualities we have are precisely those that lead us to almost all our difficulties, misfortunes and errors. (…). We are also suffering people and, as a general rule, we want to do well. I can’t think that all the faults are on our side.

Hard Times is a crusade against hypocrisies, which the author mocks mercilessly, and also a powerful reflection on the most despicable human qualities and those essential – among them imagination – to try happiness.

You must be logged in to post a comment.