Jews 2

Anne Frank describes enduring pain

Anne Frank describes enduring pain

Forced to walk on tiptoe, deprived of the outside world, longing for air and freedom, sharing with others that loneliness that persists even when accompanied, confident that the end would be “good,” Anne Frank lived her last two years.

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Photo: Cover of the book

Forced to walk on tiptoe, deprived of the outside world, longing for air and freedom, sharing with others that loneliness that persists even when accompanied, trusting that the end would be “good”, that is how Anne Frank lived her last two years.

She went from being the talkative 13-year-old schoolgirl who was always “the first to play jokes, the eternal joker,” to feeling “conscious of being a woman of moral strength and courage.”

She, whirlwind and din, independent, flirtatious, interested in the history and mythology of Greece and Rome, should be remembered not only for the causes that brought death upon her, but for the vitality with which she faced them, certain that, at the end of that terrible struggle, she would be recognized as other people and not only as a Jewess.

“I want to go on living, even after my death. That is why I am grateful to God who, since my birth, gave me the possibility (…) of expressing everything that happens in me. When I write I forget everything, my sorrow disappears and my courage is reborn. But – and this is the main question – will I ever be able to write something lasting, will I ever be able to be a journalist or a writer?”

No wonder then that, that night of March 28, 1944 while listening to the radio, all eyes around her turned to her and her diary seemed “taken by storm,” after hearing Minister Bolkestein say that at the end of the war letters and memoirs concerning that time would be collected. “Fix yourself a novel about the annex published by me! Wouldn’t that be interesting, wouldn’t it?” she left initialed in her notes on the evening.

Thanks to the memoirs she so skillfully recorded in her diary, humanity has been able to know how those eight Jews who clandestinely lived in the annex of a warehouse in Holland ate, slept, talked and spent their days, terrified by the constant bombing and the fierce fear of being “discovered and shot” by the Gestapo, all this while half the world was sinking into hunger, misery and death unleashed by the Second World War.

In Kitty – as she called “the very first surprise” she received on June 12, 1942, on her thirteenth birthday – she found someone to whom she could confide without reserve everything she was unable to express, not even to her parents and sister. Overwhelmed by family conflicts, those of adolescence and those caused by confinement, war and the feeling of being besieged, Anne gave no respite to her pen and diary, the basis of her truncated yearnings to have fun, ride a bicycle, go to school, dance, whistle, have a place in the world and work for her fellow humans.

There, amid the suffocation of confinement, she found love in Peter, the son of the family with whom the Franks shared the annex. “Every time he looks at me with those eyes (…) a little flame seems to light up in me”. Anne understood in the midst of all the horror that “he who is happy can make others happy. Whoever loses neither courage nor confidence, will never perish from misery”.

She, like so many other Jews, died in a concentration camp, just one month before it was liberated. Today, when the world is plunged in hatred and conflicts, the firmness of spirit is the best tribute to that young woman murdered by human monstrosity.

Cuba Rejected Jewish Refugees in 1939

SS Saint Louis:

Under U.S. Pressure, Cuba Turned its Back on 909 Jewish Refugees in 1939

This is the heartbreaking story of the passengers of the SS Saint Louis liner, who in order to escape persecution by the Nazis, decided to travel to Havana, and then to the United States, but upon arrival at the Cuban port, under pressure from the U.S. government, were denied

—————————————————————————————————

Author: Dolphin Xiqués Cutiño | archivo@granma.cu

March 17, 2020 13:03:41

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

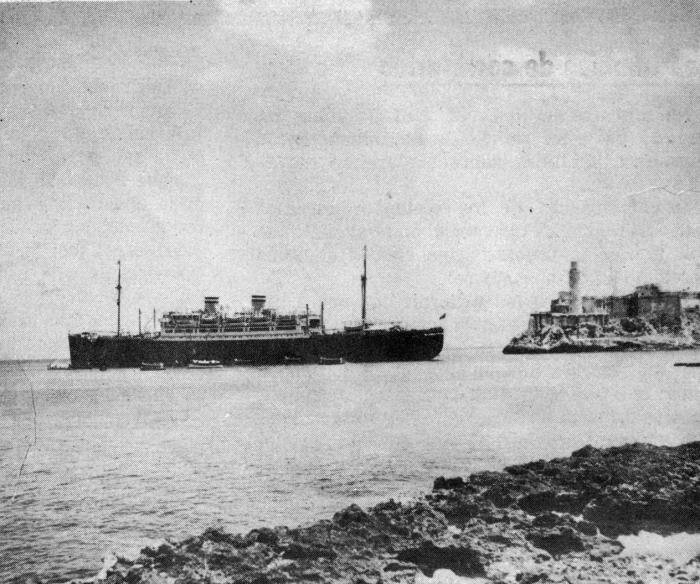

The SS Saint Louis leaving the port of Havana on June 2, 1939, when the Jewish refugees were denied landing. Photo: Carteles Magazine

This is the heartbreaking story of the 937 passengers of the SS Saint Louis liner, who in order to escape the persecution by the Nazis, decided to travel to Havana, and then to the United States, but upon arrival at the Cuban port, under pressure from the Yankee government, were denied disembarkation.

Most of the passengers were Jewish families who, with the arrival of the Nazi party to power, began to be harassed: Their synagogues and properties were burned, they were constantly harassed and, moreover, they risked being detained only because they were Jews.

937 Jews fleeing the Nazi repression were shipped to the port of Hamburg. Photo: Taken from the Internet

Also traveling were four Spaniards and two Cubans who were not Jews. Almost all of them carried their visas in order issued by the Cuban Embassy in Berlin at a cost of $200 or $300 each, a fortune at that time.

The passengers of the SS Saint Louis were traveling with the illusion of reaching Cuba and then the United States, but that did not happen. Photo: Taken from the Internet

The SS Saint Louis set sail from the port of Hamburg on May 13, 1939. Gisela Felman was 15 years old when she embarked on that unknown adventure and “she remembers her father begging her mother to wait for him but she was tenacious and always replied: I have to take the girls away for safety.”

The families enjoyed the trip without suspecting that they would be rejected in Cuba, in the United States and in other Latin American countries. Photo: Taken from the Internet

“So, armed with visas for Cuba acquired in Berlin, 10 German marks in their bag and another 200 hidden in their underwear, they headed for Hamburg and the St Louis.

The voyage took place with the usual normality of passenger ships. Games, dances, dinners, walks on deck and that its captain Gustav Schroder kept so that women, men and children could enjoy the comforts on board, knowing that those families had suffered enough on German land.

The Havanese were very supportive of Jewish immigrants. Photo: Taken from the Internet

Everything was ready for the passengers to disembark. But big was the surprise when the authorities showed up on board the ship and informed the captain that nobody could go ashore.

The Jewish immigrants were unaware that eight days before the departure of the ship from Hamburg, the then president of Cuba, Federico Laredo Bru, under pressure from the Yankees, had denied the landing permits by means of a decree. Now, in order to enter Cuba, it was required to have an authorization from the Secretary of State and another from the Secretary of Labor and to pay a $500 bonus, except for the tourists.

The SS Saint Louis in the port of Antwerp, Belgium, after sailing for almost a month through Latin America without getting any country to accept its passengers. Photo: Taken from the Internet

Of course, the Jewish refugees could not comply with the new entry regulations because they had left Germany with what little value they had left. And now they had nothing of value with them, only their lives.

Only 28 passengers were able to disembark without problems, including the four Spaniards and the two Cubans.

The SS St. Louis remained in the Havana watershed for almost a week while the lives of the 909 Jewish refugees were traded as if they were just another commodity. They were fleeing from Nazism and were caught by capitalism.

On June 2, President Laredo Bru ordered Captain Gustav Schroder to leave the port of Havana. As the ship was leaving, thousands of Havana residents came to see them off, offering their solidarity and thus showing that the Cuban people were with them.

The ship set sail escorted by two Navy boats and set course for Florida, but there they refused to receive them as they did in Puerto Rico. The captain then telegraphed the authorities in Canada, Honduras, Venezuela, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia, Paraguay, and Argentina, among other countries, to persuade them to take in the Jewish immigrants, but they all refused entry.

Almost a month after his departure from Germany, the SS Saint Louis had to set out for Europe and after long conversations some Jews were accepted by Great Britain, Holland and France, confining them in internment camps. The remaining passengers disembarked on June 17, 1939, in Antwerp, Belgium.

The epilogue to this heartbreaking story goes back to the German invasion of western Europe in May 1940: approximately 670 SS Saint Louis refugees were caught by the Nazis and died in concentration camps. Some 240 survived years of starvation, abuse, and forced labor.

Sources:

Cartel Magazine, June 11, 1939

Juventud Rebelde, March 29, 2009

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

You must be logged in to post a comment.