Isabel Moya: Challenges for women in Cuba?

Let’s not think everything has already been achieved.

By Flor de Paz, Cuban journalist and plastic artist

By Flor de Paz, Cuban journalist and plastic artist

March 8, 2018

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

Isabelita, during a conference at the Editorial. Photo: Flor de Paz/ Cubaperiodistas.

This is the last interview given by the director of Editorial de la Mujer, who passed away in Havana on Sunday, March 4. Her testimony is part of an audio-visual series that was recently recorded to dignify the work of Cuban journalists, who will be holding their 10th Congress this year.

The project, which will soon be broadcast on Cuban television, is being carried out by young graduates of FAMCA and is the fruit of collaboration between the Union of Journalists of Cuba (UPEC) and the Association Hermanos Saíz (AHS).

— Constance and strength? A trait of my personality. I am, I don’t want to use the term fighter because it has many meanings, but I am a combative woman who always believes in Anaïs Nin’s phrase: “Put your dreams on the horizon and start walking”. You never reach the horizon, we know that, but push.

The entrance hall and living room of Isabel Catalina Moya Richard’s house are very spacious, as in most Havana construction of the first decades of the 20th century. Both spaces are demarcated only by four circular columns, and are passageways for the furniture that inhabits it —sofás, armchairs, armchairs, tables— and, among the latter, a huge one that Enrique Sosa, a professor at the University of Havana and panelist for years in the television program Escriba y Lea [Write and Read], gave to Isabelita.

It’s San Lázaro Street, in the popular neighborhood of Centro Habana. The noises of the road buzz around the house like a volcano erupting. And Isabel, seated in front of the precious wooden table that Professor Sosa gave her, now supporting an old typewriter, a souvenir from La Catrina, photos with Juan Carlos, and Gabriela, the 20-year-old daughter of both of them, as well as other ornaments, talks about the image she has hanging on one of the walls of the room: “it is Frida Kahlo’s Blue House”. It was given her by its author, the Mexican Aurea Alanis, who was in Havana for a course in gender photography.

Isa and her daughter Gaby, as a baby.

—I’ve always been very gregarious, I enjoy being in a group, I’m very social, but I realized that I wanted to study journalism because I liked to write, I liked to research, I liked to read, I liked Humphrey Bogart’s films, from film noir, in which it was always a journalist who discovered everything. And I thought: I want to be that kind of person who investigates, who reveals secrets, she says, while Daniela Muñoz Barroso and Lena Hernández’s cameras “focus” on her eloquence.

During a pause, her mother, also named Isabel, also 72, reaches for a glass of water and medication. “All my life I have known what my faculties and shortcomings are. I have a degenerative bone disease that has forced me to use braces to walk since I was born. I’ve been operated on many times and during those periods I devoured books and books; of course, without order or concert, I read The Consecration of Spring, by Carpentier, as well as seven novels by Corín Tellado.

At that stage she tried, above all, to fill herself with a world of words that would allow her to live other lives in her own life. And then, in high school, when teachers began to direct their reading, she realized that she really had writing skills.

—But look, I never approached journalism as literature; I have not written stories or fiction as journalism. No, I’ve always been interested in writing essays on history or politics. It’s important to write about reality. And, of course, I’ve written poems, like everyone else, to give them to the groom, but not because they are publishable. Far from it.

…

—I would say that I had a beautiful childhood; a very happy growth process. Starting school was an important time because I always loved studying. In the fifth grade, I won a literature contest with a fantasy fiction story. I felt tremendous joy!

“I don’t forget that in elementary school my political life began, even though I wasn’t very aware of that reality at the time. Many times, we would go with Vietnamese hats and leaflets glued on our uniforms to support Vietnam in its war against the United States. Also, one of the first marches I participated in as a child was for Angela Davis’ freedom. Then she came to Cuba and I realized that I was already worried about those problems. Later, in the middle school and high school years, when I made friendships that I still have, and when my interests were taking shape, I definitely knew that I wanted to study journalism.”

…

Isabel Catalina Moya Richard was born in Havana on November 25, 1961. She is the eldest daughter of a family of four, including her parents. Their existence – marked by the impossibility of their organisms to assimilate calcium and, in turn, an optimism compensating for the lack of the mineral and all difficulties – can be summed up this way:

Isabelita, together with Eusebio Leal, Historian of the City of Havana, and Deputy Yolanda Ferrer.

On her feet, on crutches or in a wheelchair, she is still herself: PhD in Communication Sciences, director of Editorial de la Mujer and the magazine Mujeres, the Associate Professor of the Faculty of Communication at the University of Havana, the president of the Chair of Gender and Communication and coordinator of the International Diploma in Gender and Communication at the José Martí International Institute of Journalism; the admirable José Martí Prize for Dignity and the National Journalism Prize (for her life’s work), awarded by the Union of Journalists of Cuba in 2016 and 2017.

—When I graduated, in 1984, I was the first in the group and was placed as a disseminator in the Office of Nuclear Affairs, but I did not agree. My dissatisfaction did not go down well because that institution was very important at the time. However, I wanted to do journalism and, when I asked to be relocated, I didn’t know where I was going to work for three months. The second choice was Mujeres [Women} magazine, and I took it as a punishment.

“How wrong I was! There were opportunities that many of my classmates didn’t have. I know all of Cuba thanks to my work as a reporter for Mujeres. I have been in the Pico Turquino, on the black beaches of the Isla de la Juventud, in the wonderful landscapes of Pinar del Río, in the Escambray… And, as at the same time I was attending the correspondence section, one day I thought: “Oh, I’m going to do a postgraduate course in research methodology”. And so I was able to design a content analysis tool that allowed us to classify all the letters we received. We get a lot of information from them, both for the magazine’s work and for the attention to the problems they alluded to. And I was forever hooked on research.

With the support of the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC), Isabelita had the opportunity to do a course on feminism at Casa Morada in Chile, and to participate in numerous international events on gender. Until in one of her daily inner dialogues, she asked herself: “Well, I have to try to create an environment where theories of gender and communication converge and thus we will have a better journalism”. And in this approximation, her doctoral thesis is aligned, for which she received the highest grade.

In the School of Communication, Isabelita gave her first gender classes, a horizon reached by which she lets us see great passion. When thinking about it, she brings to mind, that master’s degree given in Villa Clara, “one of the adventures in which I enrolled with UPEC: the teachers had to stay there every school week”.

Then it was time to found the Chair in Gender and Communications at the José Martí International Institute of Journalism, thanks to Guillermo Cabrera, she said. In this way, a line of training and research was opened in our country, of which we can be proud today. This is because, in addition to having graduates from numerous graduate schools, some of them have done their doctoral theses on the subject.

—More than two hundred communicators from all over Latin America have graduated from our courses. Through the Chair, I have also been able to teach at several important universities in the region and in Europe. Two years ago, for the first time, I gave online TV classes to some high schools in the United States. Having students everywhere is a delightful experience.

…

It’s February 3, 2018, Saturday morning. Isabelita, in front of Daniela and Lena’s cameras, talks about the issues that move her the most. Irina, with a demanding expression, reveals her concern for the continuous sounds coming from Calle San Lázaro, but this is the daily environment in which she lives.

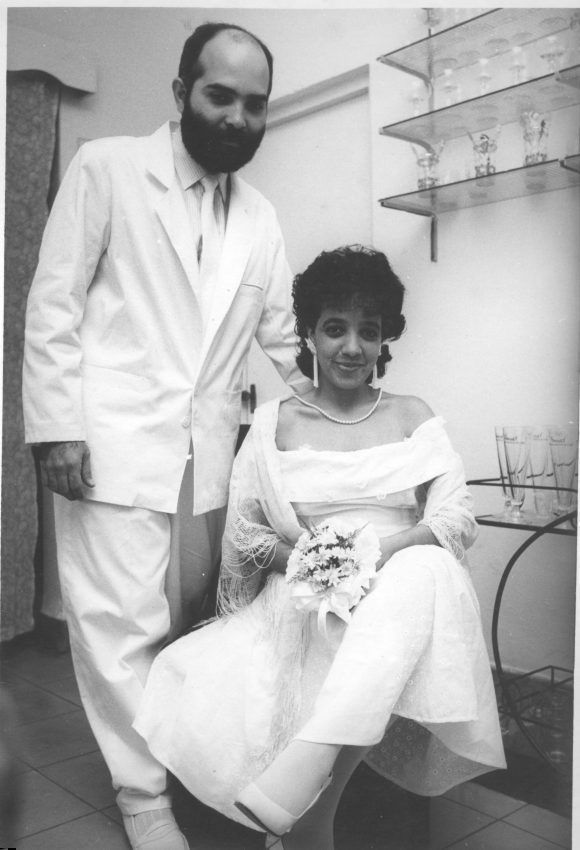

Graphic memory of the wedding of Isabelita and Juanca.

—The challenges facing women in Cuba? The first is to think that they have already achieved everything. When we look at the statistics and see the number of women in the National Assembly, the number of women scientists and women communicators, and that more than seventy percent of the prosecutors are women, and so on, we come up with a distorted idea of reality. Because we have managed to open ourselves up in professions that were not previously considered feminine, we are now in the most complex moment, that of confronting subjectivity, culture, value judgments, and customs. These are much more difficult to change, since they are based on collective imagery and social representations. This is what we sing when we sing a bolero, a salsa song or sometimes, unfortunately, a reggaeton and what the novels tell us: romantic, dependent loves.

Her reflection is based on two substantive arguments: the communicational processes in Cuba do not problematize the reductive approaches of these audiovisual spaces, nor the subjective gaps that in the seventies the media managed to tackle documentaries such as that of Sara Gómez, Mi aportación, and the feature films Retrato de Teresa. Furthermore, attitudes that unwittingly blame and associate the advancement of women with certain family crises are frequent.

Today they say, “Women don’t give birth,” but that’s not the problem. The problem is that society has put women in the dichotomy of motherhood or professional fulfillment, so society has to change in order for the couple, the family, to have more children. It is not just a matter for women because even with all the advances in science and technology, it takes an egg and sperm to conceive a human being. But the media, instead of questioning this sexist approach, return and blame women for the problem of low birth rate.

Despite being public, of representing a social system that has human beings as the center of its goals, the media in our country does not achieve a racial balance, for example, Its aesthetics are very homogeneous: the majority of women come out with straightened hair. I liked it very much that the other day I saw a young black girl with her braids on the Morning Magazine. Because, as I say, there is no problem with straightening your hair, but in that fashion, it becomes a cultural mandate that forces you to assume aesthetics with which not all want to express themselves. It is still a challenge for diversity to be understood.

Using her experience as an example of what can be done in the communication processes, Isabelita talks about a work recently published in Mujeres magazine. It was about the people who sell coffee and fried foods from a window of what was the living room of her house, of a small house. And she asks, “What about the children living in these homes, where do they do their homework? You guys get to work? How do you reconcile business and family life in a small space like that??? Oh, and what good is it, grandparents live longer, but now the child is going to marry so grandma must move out of her room, and sleep in the living room…?

I know that there are people who think that these issues are minor and that the only thing that matters is global warming, but in what happens global warming there are people who live similar tragedies every day, so it is very good that there is journalism for global warming and that there is journalism that helps in the day-to-day, a service journalism and a journalism of social activism.

Isabelita, what does journalism mean to you?

A commitment to my contemporaries, to my country, to my people; a passion, a passion that saves. I have been sick, in the hospital at terrible times, when one of those moments in which the fragility of the human body is observed. Someone passed by and said to me, “Oh, how I like your magazine”. And, listen to me, all the fears and pains have been frightened away. So I tell you, journalism is my salvation.

And she added:

Rosa Luxemburg said that socialism is not just a knife and fork problem, it is a profound cultural revolution. I, therefore, believe that journalism will help transform machismo, sexism, homophobia, racism, the inheritance of five hundred years of Western Judaeo-Christian culture, first, from an atrocious first colonialism and, later, from a capitalism that destroys human beings.

(taken from Cubaperiodistas)

You must be logged in to post a comment.