A Brief History of Tourism

Photo: Courtesy of Mintur/Granma/Archive.

By Graziella Pogolotti

May 3, 2017

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

The image of the tourist was, at first, that of a traveler who, individually, undertook an adventure in search of new horizons to gain knowledge. Thus, exotic visitors began to show up in Cuba, who very often left testimony of their experience through letters, stories or books that proposed more ambitious insights.

The perspective of others gave us a vision of our singularity in the multiple planes that natural and human landscapes offer. For those persons who come from other lands, the richness of a prodigal natural universe –unaffected by the harsh rigors of winter– is striking.

The chromatic luxury of the environment made an impact at first sight. The true singularity was expressed in the human face of a cordial country, with open doors, where the refinement of customs was accompanied by the abandonment of the rigid formalism prevailing in other lands. The deepest bond was established in the human plane and there was also the first-hand approach to a culture forged under different circumstances. Thus, the characteristics of “being Cuban” were beginning to be defined.

Later on, in the twentieth century, workers’ demands gave the middle classes the right to vacation time. Inexpensive because of geographical proximity, access to a tourist trip was within reach of Americans encouraged by the stimulus of the warm climate and the exoticism of a certain folklore trivialized by the trinket trade.

In the winter months, the high season prevailed. It offered an enjoyable warm weather and coincided with the Havana carnival. In Parque Central, a maracas player stood at the door of a store that offered cheap musical instruments, along with belts, purses, and other articles made of genuine crocodile leather.

The flourishing business imposed its perverse features. When Prohibition was established in the United States, Havana was a space open to free consumption of alcohol. Bars multiplied and a malicious substrate became linked to the contraband privileged by the vicinity between the coasts of the two countries.

With its well-known ability to forge mentalities, neo-liberal globalization has appropriated large-scale tourism, associated with what is called with apparent innocence –eternal trap of words–: the leisure industry.

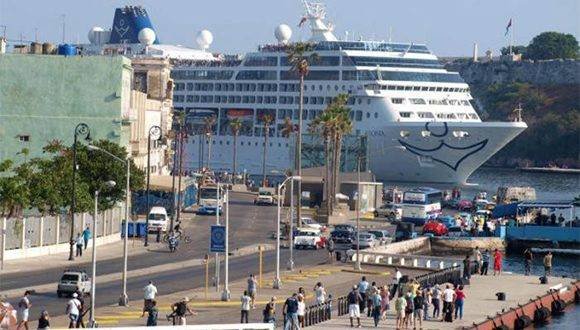

Its extreme expression is manifested in the cruises. In these, instead of observing the new, travelers contemplate each other in a coexistence that consumes most of the available time. In a tour of preset destinations, they pass through some paradigmatic sites and lunge into the search for small souvenirs, trophies to give to friends, once back home. The human landscape and the power of culture have disappeared from the picture. They will get to know, if at all, a masquerade willing to show –with roaring stridency– the expected exotic component.

Before becoming the grave of desperate emigrants, the Mediterranean’s natural environment suffered the predatory effects of tourism. There, too, on a short excursion, the testimonies of one of the original sources of so-called Western culture moved to the background

The Caribbean is the counterpart of that mare nostrum. We preserve virginal areas, but our being an island makes us extremely vulnerable. We have beautiful landscapes, but we lack abundant water resources to quench the thirst of a temporary overpopulation and maintain perfect lawns for golf courses.

In the cultural field, the dangers are even greater. While the Mediterranean tradition still evokes the glories of a dilapidated Parthenon and the infinite management of the Egyptian pyramids, –all victims of neo-colonial perspectives– our culture does not enjoy similar recognition.

Exoticism always maintains a component of underestimation, and our inhabitants have psychologically suffered from this conditioning. Expansive in the last half century, the leisure industry was already emerging, when “the Commander arrived and ordered it to stop.” [a refernence to the lyrics of a song, by Carlos Puebla, referering to Fidel putting an end to capitalist evils].

The hotels that multiplied in Havana were fronts for gambling halls, meeting points for high class prostitution, and business centers of an expanding mafia.

At that time, a master plan for the development of Havana was designed which articulated interests of a diverse nature. Speculation based on the price of the land oriented the growth of the city towards the east, where investments were made with a view to the creation of new neighborhoods.

The government would pay the expenses of infrastructure for investments with an absolute guarantee of profitability. New management centers were being directed there.

The historic city would be at the expense of the underworld. Since the space provided for that predatory universe was insufficient, a floating island would be built in front of the Malecon, for the free flow of large-scale gambling dens. The landscape value of the Malecón –complemented by the gentle hills that shape the profile of the city towards its geographical center, the present-day Plaza de la Revolución– did not matter. The capital of the country, the historical and cultural jewel in our crown, would be hopelessly dismembered.

For a country like ours, lacking in great mining wealth, tourism is a source of income of indisputable importance. The challenge is to devise strategies that enhance the possibilities of development in favor of the nation, culturally and humanly, because in the virtues of our people lies the soul of the nation.

The emergent demand for a large-scale project focused on the advantages of the availability of sun and beaches must be accompanied by the analysis of the risks involved, with the purpose of elaborating the indispensable counterparts. It is important to discard the notion of the leisure industry and to take into account that the fashion of beach enjoyment may be temporary.

Our true strength lies in our status as a large island, endowed with a multitude of possible options: many of them based on a cultural and historical tradition.

There is also the possibility of proposing designs aimed at valuing good living, latent in our large and small cities, in the varied landscape environment, and in the survival of little-explored corners made to the measure of the human being. To elaborate these projects, it would be advisable to complement the geographic and geological maps with a cultural map illuminated by a deep inward look.

You must be logged in to post a comment.