- English

- Español

Yes, Colombia DOES Want Peace

By Darilys Reyes Sánchez and Zulariam Pérez Martí

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

In the most sensitive epicenter remain the victims: those whose missing persons, lost homes or property will not be returned. / Photo: Sputniknews

In the most sensitive epicenter remain the victims: those whose missing persons, lost homes or property will not be returned. / Photo: Sputniknews

A 50.21 percent of Colombian voters marked their ballot against what the world expected. The issue has had several interpretations, not all of them accurate.

When Colombians went to the polls on Sunday, they did it to show their position on the agreement –that is: the terms, concepts, dispositions, and benefits– not on its greater purpose: peace. Although it sounds contradictory for those who watched the process from outside, those who voted agree on the desire to bring to a close five decades of armed conflict; but they do share options on how to do it.

“YES TO PEACE, BUT NOT TO THIS ONE” [#SiALaPazPeroEstaNo], became the trends in social networks before, during, and after the vote. To disagreements, mistrust was added: “The president cannot say the war is over, the kidnappings are over, insecurity is over, and Colombia is a magical country,” argued supporters of the NO. In the midst of this argument are the years of family misfortunes, deaths, kidnappings, and deep lacerations, on either side.

The results of the referendum showed internal division. Or what we think is worse: over 60 percent of the population abstained from voting on a matter of the highest relevance and priority for the country.

As explained to the 5 de Septiembre website, by Andrei Gómez-Suárez, a political scientist at the University of the Andes: “Colombia is an abstention-inclined country. The participation of Colombian society is felt in the presidential elections (…), but even in such elections, abstention levels remain above 40 percent. In atypical elections, such as the referendum, where there is no buying or fiddling with the votes, those who vote are new voters or sectors thoroughly involved with the democratic process.”

One of the recurring questions among Cuban public opinion is why the need for the plebiscite, if days before the agreement had been signed in the presence of senior leaders of the world. Clearly it was a democratic gesture, but it did not seem to change the course of events.

“It was a reasonable decision to measure to what extent the parties could count on public support for the implementation of many complex reforms that impact the countryside, crime, political participation, reparations for the victims, and investigations into those most responsible for international crimes,” said Gómez-Suárez.

Advocates of the NO argued that “they called on presidents all around the world to sign an agreement that Colombians were still studying; Why not do so once they had the certainty? Now everyone says that Colombians want to live in war, but there is nothing further from the truth.”

As never before, the Vatican, the UN, the International Monetary Fund, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the European Union, the OAS and all governments in the region supported the process. However, the final agreement is profoundly difficult to understand in a few weeks (297 pages).

“The problem was in the short times for the countersignature, says the political scientist. It was too short a time for explaining and teaching (…) In the last week the government and the FARC signed the Final Agreement in Cartagena and that was read by many Colombians as a confirmation of the YES. Many voted for the NO to express discontent.”

The logic behind the NO describes their points: “the FARC will not return the money they accumulated illegally in these years”; “only the State will repay damages to the victims”; “justice loses autonomy”; “war criminals will not go to jail “;”the agreement does not penalize drug trafficking “;” the FARC are not governed by International Humanitarian Law (IHL)”;” there is no guarantee for total disarmament “;” it weakens the Constitution … “.

Given the complexity of the negotiations, the government of Juan Manuel Santos claimed they had reached the best possible deal after four years of talks. According to the International Criminal Court, this satisfies the demands of justice. Only under these terms, and after three failed attempts in the last 30 years, did the FARC guerrillas agree to demobilize, surrender their weapons, and submit to transitional justice.

The new scenario returns former President Alvaro Uribe, defender of the NO who was until now excluded from the dialogue table, to center stage. Thus, each side equates representatives, being now the binomial Uribe-Santos the mediatic face of the conflict.

“Santos is a rational ruler; he seeks to convince of his public policy with arguments from a technical approach. Uribe does not care to be accurate; he uses colloquialisms and repeats several times the same phrases so his listeners get the message. While Uribe was exposed to the public, Santos delegated the issue to the negotiating team and civil society. It was a wise decision, but lacked finding some great emotional translators for the agreements; he stayed with the explanations of the negotiating team. This team could not counter Uribe emotionally,”Gómez-Suárez said to this newspaper.

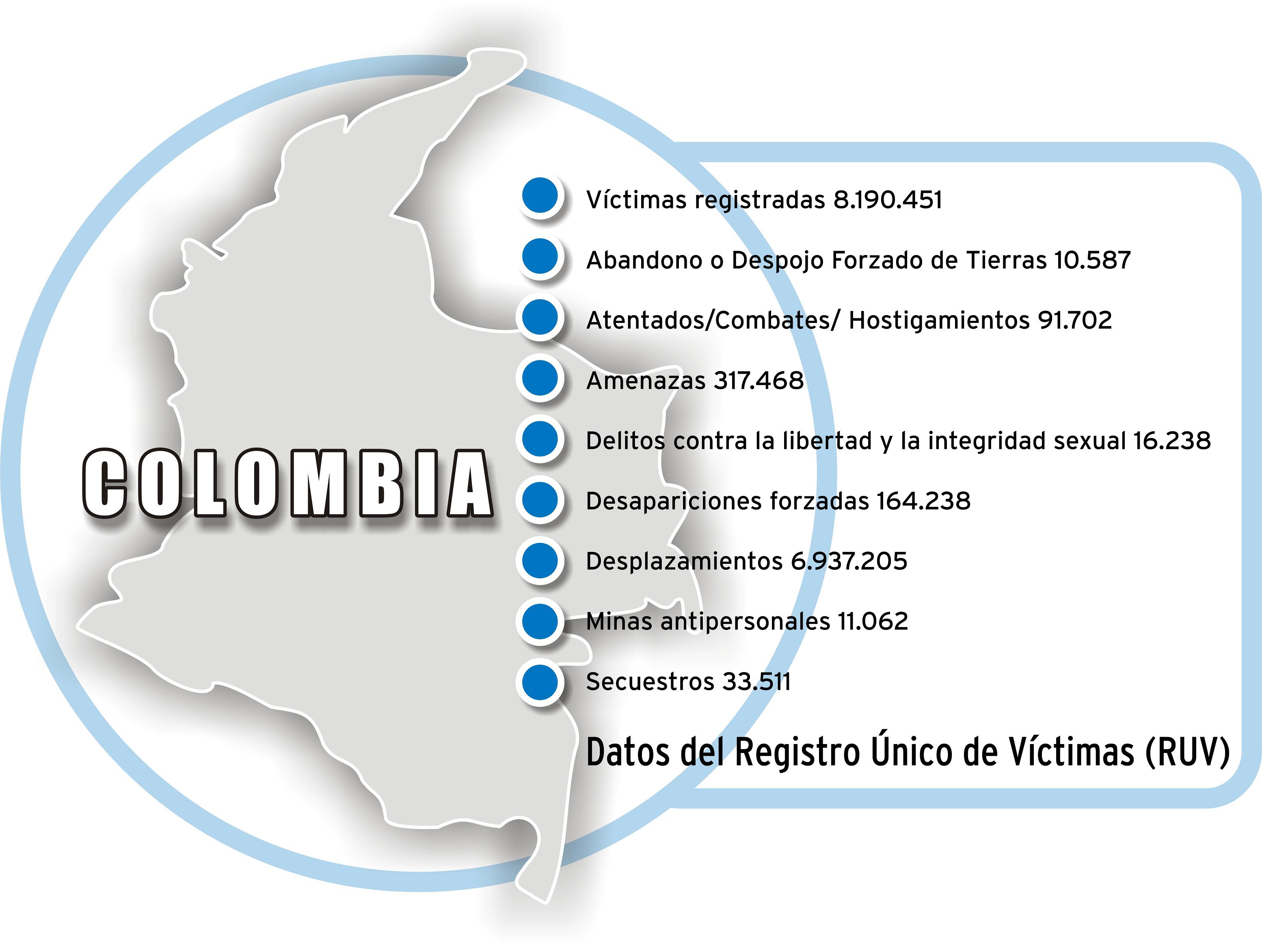

In the most sensitive epicenter remain the victims: those whose missing persons, lost homes or property will not be returned. Still, many backed the YES with the aim of ending a conflict that has claimed about 267,000 lives in five decades.

For now, the future path for Colombia seems difficult to predict: “There is much uncertainty, says Gómez-Suárez. They are two parallel and complementary situations. On the one hand, a meeting between President Santos and former President Uribe will take place. This meeting should lead to a meeting with Timochenko. (…) This meeting will be essential for the parties to commit themselves to make the implementation of the agreements viable.

“On the other hand, civil society is promoting actions on the streets to support a negotiated solution to the armed conflict. Youth and social organizations are seeking to involve those who voted YES and NO to make a silent march for peace. No political posturing. If the political pact does not allow endorsing the agreements, social mobilization almost certainly will trigger the realization of a Constituent Assembly. “

From inside, reality could be much more diverse than what is reflected in the media; only Colombians understand it in all its magnitude. Perhaps they failed in this political consensus because the deal was agreed upon bilaterally and civil society got involved late in its implementation. So after the NO in Colombia another lesson emerges, and it shows that the process comprises more than two parties, more than two visions on a universal right: peace.

Andrei Gómez-Suárez, Ph.D. International Relations, Master in War Studies and Contemporary Peace. He specializes on Armed Conflict Resolution. He is a Political Scientist at the University of the Andes. / Photo: Internet

Spanish Headline Here

Por Authors Name Here

Espanol Here

You must be logged in to post a comment.