Talking About the Party (I)

Reducing the socialist revolution to the protagonism of a party or an ideology does not help to understand its complexities and problems.

By Rafael Hernández

March 17, 2021, in With all its letters

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

Photo: Randdy Fundora

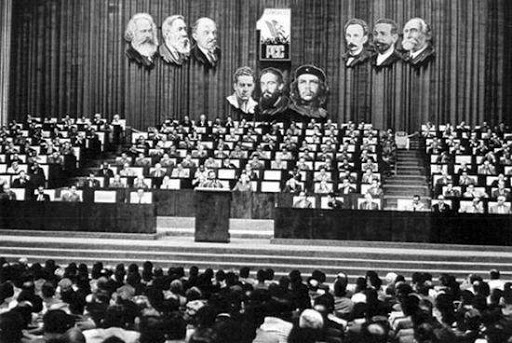

First Congress of the PCC. Held at the Karl Marx Theater in Havana, December 17-22, 1975. Photo: Archive

Antonio Guiteras. Photo: Bohemia Magazine

Surprising as it may seem today, those parties, including the Autenticos and the Ortodoxos, opposed to the dictatorship, were left on the sidelines, while people went out to do politics in the streets. Most of those people could not remember when exactly they ceased to exist.

Nothing less than the armed forces, that backbone of the old regime, would be uninstalled, to put it in the jargon in fashion today. No wonder Fidel Castro, who was neither the president nor yet the Prime Minister, was from the beginning the Commander-in-Chief of those newly installed forces, made up of “the uniformed people,” as his head of state liked to say, a smiling Camilo Cienfuegos, who at 27 was not, however, the youngest guerrilla commander.

How the structure of power and the prevailing social order in Cuba in the 1950s could have admitted an “agrarian and anti-imperialist revolution” without it entering from the beginning into the radicality of a real social revolution only makes sense for the codes of that Marxism-Leninism, and in the hypothetical revolutionary scenarios that the Comintern manuals enunciated.

The difference at the outset, when adopting an insurrectional strategy, was concrete political action, which predetermined the type of power at the head of the revolution from the beginning. When it clarified that socialism is reached “by successive preparatory stages,” of which that Program only outlined the first, it was assigning to the “stages” a completely different meaning from those established by the Comintern.

From this perspective, the social conflict was not brought about by interests and factors of power, but by ideology, and cultural representations, such as those of an enemy “that had to be national and foreign at the same time, a monster in which the evil of the empire and the vileness of the traitors could merge.” This parallelism between apparently exclusive visions, brought together in an approach that replaces historical analysis with literary phrases, and the logic of a social revolution by what philosophers call a teleology (of good or evil) confers a curious code of kinship, not at all by accident.

***

To be continued

You must be logged in to post a comment.