El Caimán Barbudo

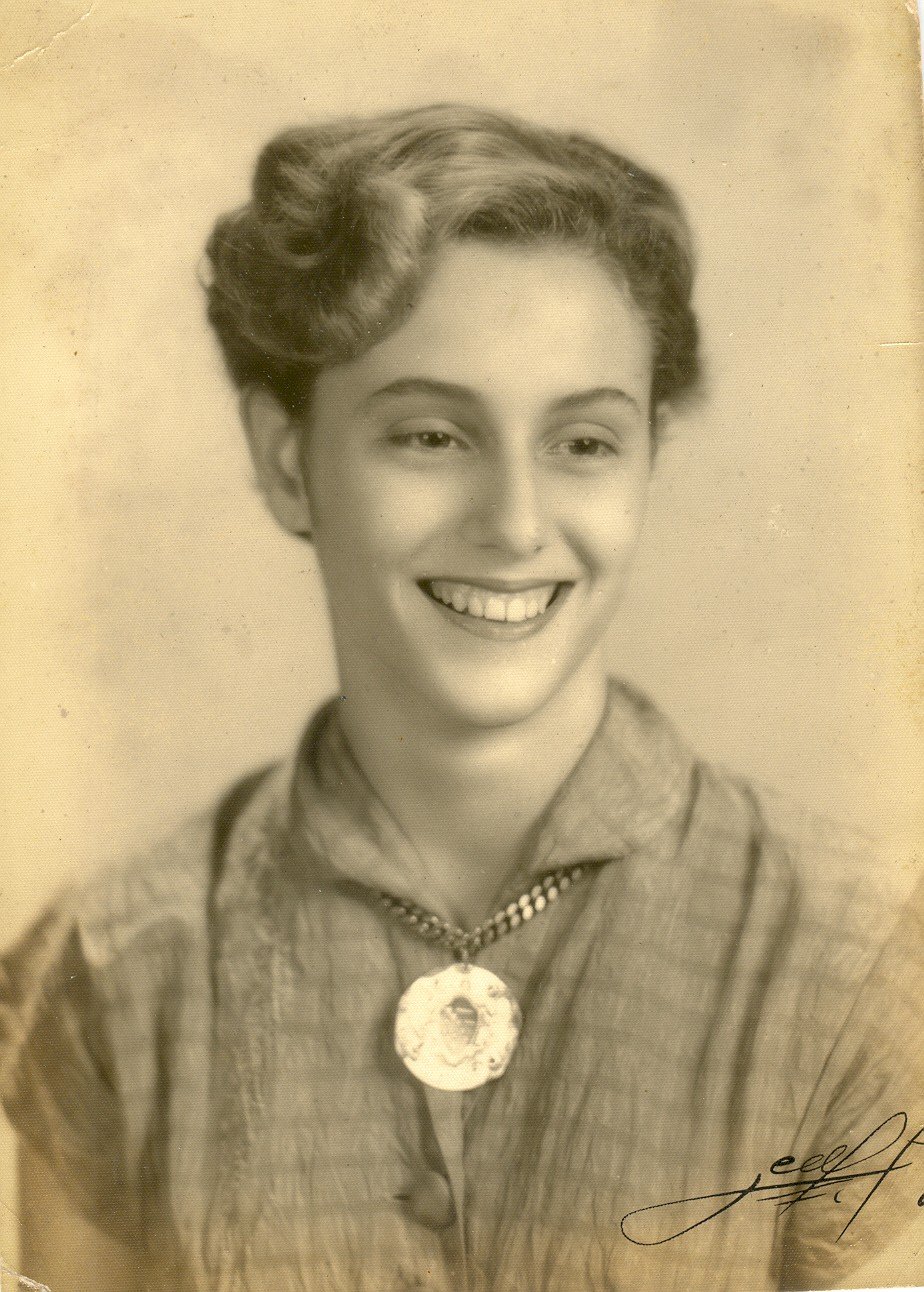

Natalia Bolívar, Wisdom of a Witch

By Dailene Dovale

October 4, 2020

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

It is December 31, 1958. Natalia feels depressed, in a rented house. She is alone, or almost alone, because around her instead of grapes and happy relatives, she has guns, weapons of all kinds. Natalia Bolívar Aróstegui, the charismatic girl of the Havana aristocracy, barely has a peso and spends it on elementary food and a bottle of Bacardi Rum.

“I drank it at the top of the bottle”, she will say decades later, when she turns her gaze to the past and remembers herself sad, with her friends of the Revolutionary Directorate in the Escambray Mountain Range and she is waiting, waiting for an attack they were planning against Batista, waiting for a change. That night she hears persecutors passing by on 31st Street. The tyrant fell, and Alberto Mora, head of action and sabotage for the Directorate, warned her the next day. The Revolution triumphed.

It is difficult to imagine the life of ups and downs and vagaries of Natalia when they set foot in her home on Friday, September 13, 2019. A place of peace, where the breeze and clarity pour in, there are colorful sunflowers moving to the rhythm of the wind and a moving view of trees and red tiles. It is difficult. It is necessary, then, that Natalia arrives with her dress of flowers and her blue shoes, toad style, to count in a low but firm voice the summits and depressions where she has walked her existence.

– Let me see if I can open this – she apologizes – I drink a lot of water because I am diabetic – she says and clears her throat, after taking her favorite place in the room, a mahogany balance with blue lining.

– And the coffee? – he asks his daughter Natacha, with a somewhat tough look, dark clothes, the main help in writing her memoirs.

– They already gave me coffee – I clarify.

– She has, but I haven’t – claims Natalia. And the daughter blurs as quickly as she appears.

During her childhood, Natalia studied at an American school, the St. George School. The contrasts are there since that time. She speaks English in class, and then enters the domain of the Spanish language at home and feels the powerful influence of Isabel Cantero, Chicha, her black nanny.

Chicha’s mother, a slave of the Cantero de Trinidad, came to Natalia’s family as a gift to her medical grandfather. “My grandfather was not a slave and he took her in as part of the family. When she gave birth to Isabel, she was raised with great love”.

When the grandfather dies, Chicha moves in with Natalia’s mother and becomes her manager, takes the children to the park, takes care of them and pampers Natalia. They join. She is their main source of love, while her parents, María Teresa Aróstegui and Arturo Bolívar, who is related to the Liberator of America, play the strictest and toughest roles to form a disciplined girl, ready for work and adult life. Then Chicha becomes the nanny of his daughters Natasha and Bubby. In her old age, Chicha goes to live in Trinidad with her family. She survives the hundred years and leaves in Natalia the wisdom of the Afro-Cuban religions and culture.

– Miss Lidia, you have death behind you – says a Matanzas santero to a renowned ethnologist during one of his investigations. – With whom, with me?

– Not with you, with the one who comes behind – and points to the then very young Natalia Bolívar.

Natalia is a disciple of Lidia Cabrera. She meets her at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, where she arrives as a guide at the hands of Octavio Montoro, a relative who connects her to Martha Fernández and a group of women who planned the foundation of the palace. There he approaches the ethnology room and finds in Lidia another inspiration to continue studying the Afro-Cuban culture. She also discovers José Luis Wangüemert who marks her entry into the Revolutionary Directorate (and becomes an unforgettable love). To be found, she also finds an omen of death.

– Then there it sounded to me everything that was going to happen in two weeks. I was going to fall prey to death, to tell my family. Imagine, I forbade my family to talk to Lidia. And then he gave me Oggún’s necklace, which is very pretty, and he said: “When they come looking for you… because they are going to come looking for you, you hook this necklace that I give you, with Ochosi’s arrow that is for protection against the police and all the henchmen.

When you are apprehended, you hook the necklace under your blouse.

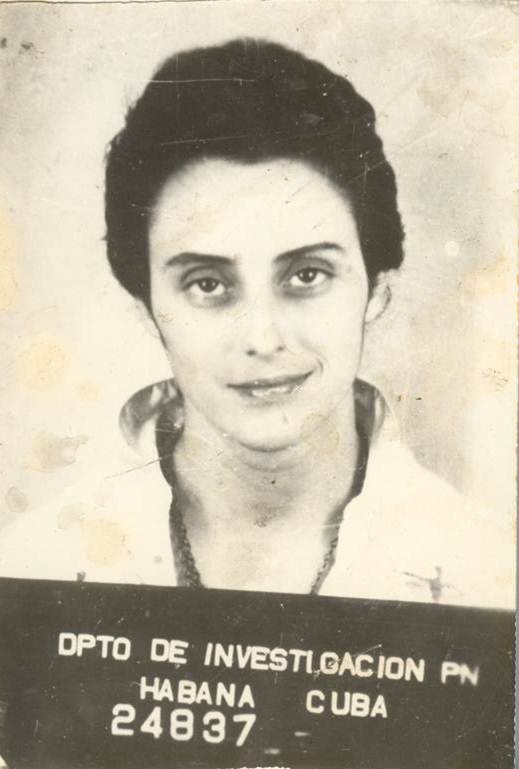

She is taken to the Bureau of Investigations, it is the 24837 dam. (“Play the ball and it comes out”). In the Laguito they show her the cement block where they were going to put her and throw her into the bay of Havana if she didn’t say all the security houses where, for example, Raúl Díaz Arguelles and Gustavo Machín were sheltering. She resists in silence.

– They started hitting me and putting things in my ears. That’s why I’m deaf. My family is mobilized, but they call Julio Laurent, a guy who’s more of a killer than Ventura. I’m scared! This is already dying, I said to myself. I played a hot-cold game with him.

What do they call you?! They shout. She has several names. Rosa and the Witch, because of all the necklaces she was wearing. What’s your name?! They repeat I don’t know what your name is! They have caught you, they threaten you, because in her house they found papers, bonds that she kept for those who were leaving the country or going to the mountains.

What do you do with that necklace, you who are Catholic, Apostolic, Roman? Just then you understand everything. That was the godson of the old man who foresaw his capture, and the necklace was the same one that the killer had received when he became a saint. From there they start talking in Yoruba. A tense dialogue, which concludes when he says:

– What do you want?

– What do I want? That they look for my mom and bring me a sandwich with a chocolate serum – she answers that day with her mouth full of blood, and now, as an old woman, she smiles when she thinks about how close she came to death.

“I felt like eating something or taking something cold. My mother arrives, she is very nice and almost all the phrases were converted into French when she said that Laurent is the murderer. And I, shut up, don’t say that we don’t even go out at Easter”.

They let her out and she immediately goes to the Brazilian embassy. She only brings one piece of clothing. Then she is joined by her friend Raúl Díaz Arguelles.

Two weeks later she leaves the Brazilian embassy and goes into hiding. He never thinks about leaving his country. He rents houses. He hides his identity under other names. She is already on file with the entire police force. She does not give up, they attack the Fifteenth Police Station. She takes Raúl and Tabo Machín with Frank Arango to a small town near the Escambray. “He returned with Tabo’s cousin, the house he had left in Orfila was full of weapons. I had to take care of all that”. There she was surprised on January 1, 1959.

Natalia becomes silent. “I’m going to have to go to the bathroom,” she interrupts. As she leaves, she goes through her room: paintings on all the walls, little bird rattles that sound in a constant jingle. In my hands I discover a lock of white hair; it is Natalia’s and must have flown towards me in one of those breezes that cross her home.

A traitor to her social class, she is accused by her family when everyone follows the path of migration and she stays in her beloved Cuba. Despite the sadness of seeing her loved ones leave, despite feeling that the Board of Directors was being humiliated, she could not walk away.

“I took Fine Arts with the guns. I was the director for six years, I did the Napoleonic Museum there because Julio Lobo left me the entire Napoleon collection. Many of the collections are in the museum because they were left to me. Always with the lawyers of the owners and the lawyers of the museum, we made the minutes with a delivery, how shall we say, of indefinite loan. They would leave things to me to protect them. You know that in revolutions looting is common. That’s why they threw me out when I didn’t allow the sale of artworks.

– What year was that?

– It was in ’66. They threw me out and sent me to clean graves in the cemetery, but those are such nasty things… – and it leaves the idea in a fine thread that fades into thin air.

Alicia Alonso and Natalia Bolívar

“What did I go to, Natalia, after? They moved me right away. Do you know why? I was a character at that time. I knew all the writers and all the artists from before… I knew them all very well. I complained and after that they sent me on my way… Do you know what “on my way” is? With the iron things opening a hole in the rocks at the exit of the Havana tunnel, in Pastorita’s famous apartments. The already created National Council of Culture sends me to work with the iron rod to break the rock.

“My life is very complicated,” she repeats, evoking the guagüeros who used to collect money on the buses and, after eliminating that post, work with it. They are all abakuá. Moved by a Natalia, recently given birth, weak and very thin, they decide to help her. “Natalia, you stand here in the hole, take the iron, throw it there, you pretend you are opening and we open next to you”.

Her pilgrimage through the world of work remains just as eventful. She is an administrator of a blumber factory, an administrator who studied four months at the Louvre Museum and knows how to handle two languages, for example.

“That’s where they got me from. Where do they get you from, Bolivar? She lands, like a damaged UFO, in agriculture. First in supplies, then in agricultural plans and in the Nazarene command post, where she serves as a translator for the presidents who come from all over the world to see the Ten Million Dollar Sapphire.

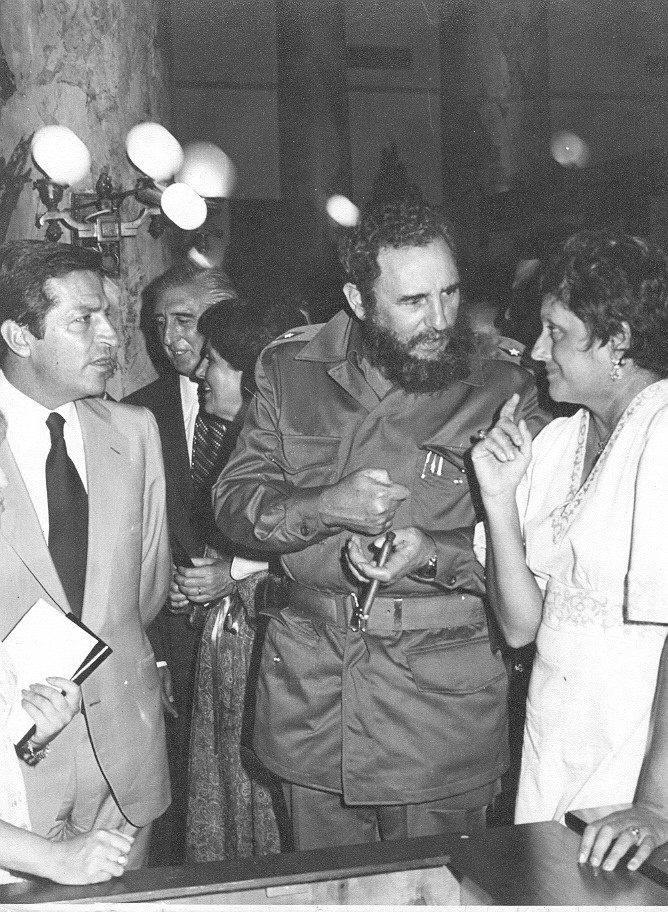

“I had a good time because I was in an environment that was more cultured and interesting. Many presidents passed through there and with Fidel several times. Sometimes he was upset about something and he would get involved with who he was with, with the King of what I know, and I would say that I am not going to tell him. It was a lot of fun, really.

The laps continue after the failed harvest. From the duck, goose and chicken breeding plan to the jewelry store at the National Bank of Cuba and the Numismatic Museum, located in the oldest bank in Cuba. Upon arrival, everything is stained with dye. They clean the floor with iron-bristle brushes.

With Fidel Castro

The museum of a subject as arid as numismatics becomes a sensation among ambassadors and personalities of culture. Music, ceramics, painting converge there…

On one occasion, Adolfo Suarez, the first president of post-Franco Spain, visited with Fidel Castro. For Natalia this fact – Fidel talking all the time with her and Adolfo Suarez and not with the then Minister of the Bank – caused her to be fired from her job.

“That was in 78 or 79, they left me a year and a half without a salary and without being able to work with either Alicia Alonso or Sergio Vitier. One day I said I was going to kill the minister.

Her friend José Alberto “Pepín” Naranjo, worried, asked her why she was harassing the minister and she told him the truth.

“They sent me to say how much the state had to pay for the year I was out of work and out of money. I survived because my mother had money in the bank.

Not only did her impeccable work arouse suspicions. In a country of workers and peasants, she proudly defends her aristocratic ancestry. And to top it all off, she denies any political party “that forces me to do something I don’t want to do.

It’s the middle of the Special Period, in a restaurant in Old Havana, under the promise of a steak and a cold beer, she and a babalawo friend of hers are talking. The waitress interrupts, “lunch is ready”, she warns them.

– Hey, stay here – he keeps her.

Then a trucker arrives with a box of books. And silently, as if carrying the holy grail, he gives it to the bartender.

– Hand me that book, let me see it.

– No, you have nothing to do with it – the bartender spits.

– Hand it over!

– What do you want it for?

– Get it for me! Natalia, look…

– Hey, I have nothing to do with Marx, Lenin or Engels, so why should I open it?

– Open it – he says.

“It was The Orishas in Cuba, with a cover of complete works by as many communists as there may be. The guy was selling it for a hundred pesos, and a hundred pesos before that was a hundred pesos. I’m leaving like a wildcat, I’m eating the steak, of course, and I’m leaving for Uneac. Look at what you are doing. He gave them a changó. The choricera was formed, as one would say in good Cuban. They closed the printing press. The police got involved. And they had to present my book, and it was Cuba’s bestseller.

The book is the result of collaborations with filmmakers such as Titón, who sought advice for their films or plays. The book, which received the unconditional support of her psychiatrist friend Beatriz Begoña, was born five years late and in the midst of an unprecedented popular reception.

During the presentation of The Orishas in Cuba

“We did a coconut shoot, with all the people who had helped me make the book and who were already dead: my psychiatrist, Enrique Rodriguez Roche, Lidia Cabrera, people who were dead and I put a scribble with the names on top of them.

Scribbling, he says, is what Elegguá is put on a chair. The presentation-homage was accompanied by Arsenio Gutiérrez’s group, with drums and songs. She and Reynaldo González are in the garden of the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba, surrounded by so many people that the Special Brigades are necessary. Days later such a scene is repeated in the Cuba Pavilion. A line of three days and nights. Some friends fear for their safety.

“Natalia, you have to find yourself a bodyguard so that you can go with him, since you are going to go alone, they are going to kill you, that’s full. And she who doesn’t, for the people there is no need for protection.

Next to the room there is a small studio, full of books, photos of Natalia, Natalia with her daughters, Natalia alone. Her daughter Natacha, who now brings a smile, is looking for her mother’s iconic photos. “At different times, she always likes to dress up. Even on birthdays, she still dresses up sometimes.

Working with Natalia is easy but very complex. Sometimes they do not agree because “we are from different generations”, admits Natacha while she checks, folder by folder, the moments of celebration, of trips, with Lidia, with Eusebio Leal.

“She is the lead singer, we are all together, but for now, everything is fine”.

They can have small discussions but always reach a consensus. Natalia is quite incisive when it comes to putting a period or a comma. They both learn.

“Listen to everyone. You learn from everyone, because even the least educated man teaches you something,” Natacha confesses. It is one of the teachings she sees in her mother and, above all, being a good friend. “Even if her friends are in the worst stage of their lives, she always stays by their side”.

And it is true. In the Elogio Oportuno, a space coordinated by Fernando Rodríguez Sosa, she signs the book La sabiduría de los oráculos (The Wisdom of the Oracles) with a little brother-in-law that says her name in Mandarin and draws a little Cuban flag on some of them.

“Natacha, give her the address and phone number,” Natalia orders if anyone asks for a contact or another opportunity to have her near. And then, in front of a pink and white cake – in celebration of her 85th birthday – she will remember again Lidia Cabrera, Fernando Ortiz and all her friends who opened the doors of being Cuban and knowing how to be Cuban. “Thank you for this. All my thanks to them”.

But no feeling is pure and happiness has nuances. This is a painful moment, as he confessed that Friday afternoon. “Seeing Havana, which is my Havana, how it has been destroyed. That has given me such great pain, destroying the great houses, the great stories of Cuban architecture”.

“And if someone dares to ask you why I haven’t left my country… I’ve traveled all over the world, but this is my country,” he stresses almost fiercely.

No one can take away Natalia’s Cuban identity. “I didn’t last more than a month outside my country. And if you ask her who Natalia Bolivar is, she will immediately say: “Cuban”. She needs nothing more than a root to her island deep in her chest.

You must be logged in to post a comment.