“His greatest work was his own life”

By Felipa de las Mercedes Suarez

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Posted on September 25, 2016 • 16:40 by Felipa de las Mercedes Suarez Ramos.

Trabajadores

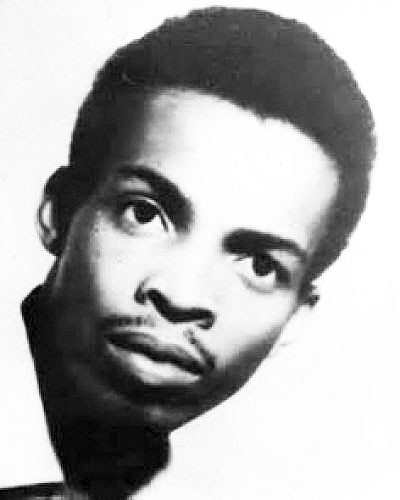

Gerardo Abreu, Fontán, distinguished himself by his integrity, morality, austerity and personal example.

Great affection, admiration, sorrow and respect, make up the amalgam of feelings that the face of Dr. Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada reflects while speaking of Gerardo Abreu, the unforgettable Fontán, his leader in the underground struggle against the tyranny of Fulgencio Batista.

His personality came to Alarcón clad in a legend because “they all spoke of a so-called Fontán who was a great organizer, a great leader. I imagined him as a tall, strong guy, someone generally described as a “big man”, hence the impression I got when I first met him; he was rather short, black, slim, soft-spoken, very polite, refined and serious, a man of few words who gave the orders very firmly, but gently; a curious character, despite his youth.“

Alarcón was active in the Youth and Students Brigades of the 26 of July Movement, the organization initiated by Antonio López Fernández in 1955. In October the following year, when he left for Mexico to join the preparations for the Granma expedition, he gave his deputy, Fontán, the responsibility of the brigades located in the city of Havana.

“Gerardo, born in a poor neighborhood in the city of Santa Clara on September 24, 1931, began to work from very young in anything; his best known job was as reciter of Afro-Cuban poetry, which he did very well. Despite his very basic level of education, merely fourth grade, he became an educated person with a great sensitivity; he liked poetry, literature… He was not the kind of person I had imagined.“

An Unsurpassed Organizer

“It has always been said –and it must be repeated– that he had a tremendous ability as an organizer, his dedication to the struggle and work. We are not referring to a person leading an organization with resources, who had cars at his disposal … He moved on foot or by bus, those were his means of transport. That’s how they caught him on Infanta Street.”

In connection with Fontán´s organizational capacity, our interviewee points out two crucial and revealing moments, one was in November 1957 when the famous night of the 100 bombs –actually small artifacts that caused no victims– that exploded in many neighborhoods of Havana after the traditional Cannon shot at 9 pm, which caused policemen and patrol cars to move frantically from one place to another.

“The other was on February 7, 1958. He had been arrested and we were convinced that they would kill him quickly: first, by the fierce hatred that the henchmen of the regime felt for him, and second, because he would not say absolutely anything. No one had the slightest doubt that he would not talk; he didn’t even give his own address or his name.”

“They knew that a guy known as Fontán led the strongest organization, the Youth and Student Movement Brigades of the 26 of July Movement in terms of organization and number of members within the whole kaleidoscope of existing revolutionary forces. We tried to make sure his arrest became known in an attempt to save him.”

Gerardo was “an example I wish we could reproduce today in our society, because it’s what we need most,” said Dr. Ricardo Alarcón de Quesada.

Havana’s Student Response

“At that time there were constitutional guarantees, but Batista suspended them due to the student strike that the death of Fontán generated: a tremendous movement that started spontaneously. As soon as the news spread, students began to protest in several centers. After that it became organized and the Federation of Students of Secondary Education called for a strike that was already underway. This lasted for three months and two ministers lost their posts.”

He describes the paralizing of all student centers in the capital: centers of Secondary Education, the schools of Teacher Training, Commerce and Arts and Crafts; private universities like Villanueva, La Salle and the Masonic; as well as private academies, whether religious or not.

“All of them, without exception, went on strike, and it did not start because the leaders, the organizers planned it; but because people desperately tried to save him. The next day his mangled corpse was found, next to the Palace of Justice. They did horrible things to him that it’s better not to describe.”

Alarcón notes that the best proof that he said nothing is that “we are alive, because he knew where I was; also where the heads of neighborhood brigades were and others, because although for many Fontán was a legend, he knew practically everyone because he organized them step by step, neighborhood by neighborhood. Something really impressive.”

“So he was the undisputed leader of the most advanced members of that generation of youth, many of them white, supposedly more educated than he; but nobody ever questioned his leadership. He was the one who knew best, the most intelligent and educated; really a very curious phenomenon, because in such a society, people like him were doomed to misery, to the worst.”

“Gerardo was like an exception, a miracle to which no youth of his social status could aspire. I don’t think anyone has an explanation for this mystery, because he was not dragged down by the vices and phenomena that harmed a lot of people at that time.”

“There is also something that has been said about him and we should not tire of repeating: his integrity, his morals. He taught us absolute austerity, and did so with his personal example. He was incapable of using a single penny of the Movement not even to eat. He could go hungry, but the funds he had raised –by selling bonds and other ways– were untouchable, and he educated us in that spirit.”

“I think a lot about El Negro [as friends called Gerardo] at that time, when there is so much talk about certain phenomena in Cuban society, and I wonder what he would think, because in that Cuba of widespread corruption, selfishness, lack of solidarity, Gerardo was exactly a master of the opposite, not a teacher who gave you heavy spiels but because we saw how he lived, how he went around walking or by bus. It was like that all the time.”

“He was impressively austere, and had a peculiar sense of leadership.. I think none of us who knew him ever questioned his authority, and we are talking about a Cuba where racial discrimination was very strong. When he gave orders he did so with few words, very concretely, and you perceived that he knew things better than you did, that he really knew what to do, and also he spoke very gently, very serenely.”

“In Cuban society at that time, where frustration and disappointment predominated, you needed to cling dearly to the moral and spiritual values, and to the idea that there could be another world, another life, an alternative.”

“And Fontán embodied that, because he was simply the best example, who came from deep down, from the lowest ranks of Cuban society, doomed to be a failure in life, as were all the poor people of this country. The fact that he lifted himself up and became an example to all was a feat.”

“I think that was largely due to himself, who, had he not been murdered, would have become one of the main political leaders of the Revolution. Surely one of the most valuable intellectuals, because he had an artist´s vocation, but his greatest work was his own life, extracting himself out of that very hostile environment to become an example that we could hopefully reproduce in our society, because it is what we need most.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.