LaJornada 3

The symbolic assault against Cuba

The symbolic assault against Cuba

The symbolic assault against Cuba

By José Ernesto Nováez Guerrero*

Sunday, May 30, 2021

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

For decades, the big cartelized media have been practicing the permanent symbolic assassination of Cuba and its revolution. The great sin of the island, in the eyes of these hired assassins of the word, is and will be to try to build a social order different from the one that prevails in the contemporary world. Cuba’s main danger lies in its example.

The Cuban political process is rooted in a beautiful and complex symbiosis, where the ideals of sovereignty and social justice that make up the project of nationhood of the 19th century and that have in the figure of Martí one of their highest expressions, find their political form and definitive realization in the socialist practice emanating from the revolutionary triumph of January 1959.

The symbols that sustain the Cuban nation have a double revolutionary sense: the independence and liberal sense of the nineteenth century and the national and socialist sense of the twentieth century. Both senses complement each other. Between both revolutionary processes, as a nourishing bridge, stands the vital practice of figures like Mella, Villena, Guiteras, Fidel, etc. In their thought and action Cuba found its revolutionary reworking the project of a country that had been frustrated with the gringo invasion of 1898 and the subsequent political and economic subjection. These were a result of the penetration of the northern capitals and the treacherous Platt Amendment, which gave the powerful neighbor the right to intervene in the island whenever it considered it necessary.

In this double character of the symbols of the Cuban nation lies one of the spaces of dispute. Anti-communism rescues the symbols of the 19th century in what they are most liberal. It ignores that continuum of ethical aspirations that Cintio Vitier described so well in his book That Sun of the Moral World, which gives a unitary sense to the totality of Cuba’s revolutionary practice and aspirations.

But it also confronts the two Cubas, the one before and the one after 1959, presenting the former as the paradise of opulence that was only for a few and the latter as the image of destruction and ruins that it is not.

To construct this narrative, they appeal to actors of the counterrevolution that we could call traditional, but also to new operators, oriented to population sectors where the economic crisis, the emerging liberal ideology and certain errors committed in political practice have created moods that can be used as part of subversive agendas.

The work with young people, the sustained attack against culture and institutions, the greater awareness of historical dates and their symbolism demonstrate a more careful work at the time of constructing the narrative of subversion.

This symbolic assault counts, in the current Cuban scenario, on an important tool: social networks, mainly Facebook, where more than 70 percent of Cuban Internet users are currently located. This network, following clearly ideological matrixes, makes visible and reinforces certain contents while isolating others and arbitrarily blocking or closing accounts and contents that in any way reinforce the symbolic position of the Cuban revolution. This has been the case, for a long time, with information related to Cuban vaccine candidates or with the accounts of important news sites on the island, such as Cubadebate.

Behind all these processes of practical and symbolic subversion of the established order are the interests of big U.S. capital. Cuba represents a double challenge for imperialism: to have broken with its domination and to demonstrate that, in spite of the growing hostility, it is possible to advance in the construction of a more just society.

To wage the symbolic battle for the nation in these circumstances implies, above all, the clarity that building an alternative social project to capitalism requires a constant educational effort to make people understand and interact socially on a new logic. It is necessary, as Che Guevara pointed out, while building new relations of production, to form a new person, one where material stimulus and individualism are no longer the main engines of his social practice. It is a difficult task, but not impossible.

It is also necessary to understand the necessary process of renewing and visiting the symbols. These are not cold stone, but are the sap in which the projects of human beings are reflected, nourished and grow. Cubans are, like all peoples, a great mixture of past, present and future. Today the symbolic Cuba is as much Martí and Fidel, as the small bulbs of Soberana and Abdala.

* Cuban journalist, writer and researcher.

Twitter @novaezjose

On the life and legacy of MLK Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr., comments on his life and legacy

Author: Víctor Fowler

lajiribilla@cubarte.cult.cuJanuary 01 to January 25, 2021

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

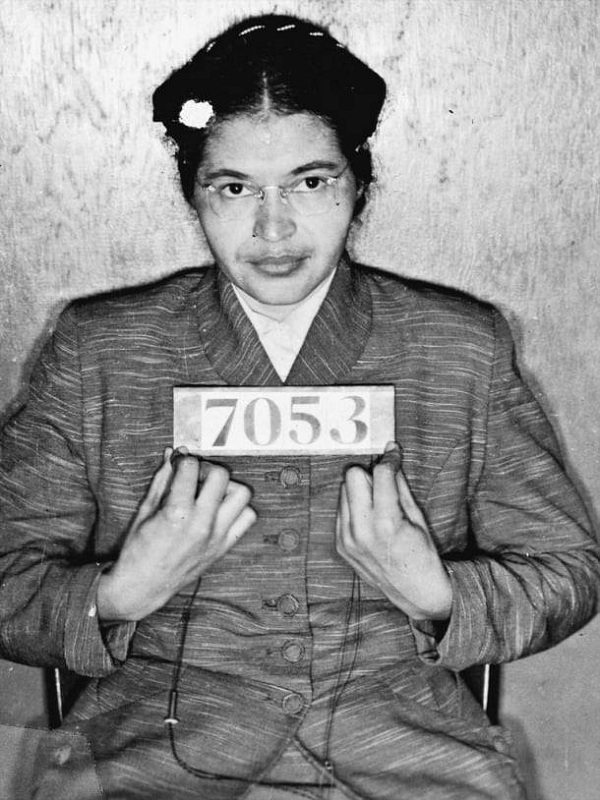

On December 1, 1955, during a public bus ride in Montgomery City, Alabama, a 42-year-old black seamstress named Rosa Parks refused to give a white man the seat in which she was sitting. The codes of segregated behavior at the time included that Black people (in the southern states) paid their fare by boarding at the front door, where the driver was located, alighted to re-enter the bus now at the rear door, and only then sought accommodation in the back seats. Black people were not even allowed to walk through the aisle of the bus between white passengers to the back of the bus.

If they acted otherwise, for example, by remaining seated (which is what Parks did), the driver – who, in all likelihood, would offend the offender – was to call the police to take them to the station and, later, to try and punish the Black man or woman foolish enough to violate the rules. A little more than ten years earlier, Parks herself had had an altercation when, after paying, she refused to enter through the back door; on that occasion, rather than be arrested, Parks chose to leave the bus.

“Segregation in theaters, restaurants, hotels and buses was a constant irritation in daily life and an insulting nuisance.” Photos: Internet

The above episode is known as one of the main moments, the detonator, of a protest of leaders and, in general, Black demonstrators who – opposed to this segregationist practice – maintained a boycott against the company that extended, heroically, throughout a year and that would draw the attention of the mass media of the entire country to the violence and cruelty of racial discrimination in the South of the American nation. As stated from the very beginning of the volume Civil Rights in America. Racial desegregation of public accommodations. A National Historic Landmarks theme study:

Physical separation of the races in public accommodations was an uncomfortable and degrading practice for those who were denied equal access. Segregation in theaters, restaurants, hotels and buses was a constant irritation in daily life and an insulting nuisance. This resulted in direct confrontations between racial minorities who demanded their right to pay for goods and services in the marketplace, and white business owners who demanded the right to only serve whom they chose.[i] The segregation of theaters, restaurants, hotels, and buses was a constant irritant in daily life and an insulting nuisance.

The roots of the problem extend to the beginning of the 19th century when the northern states of what would become the United States of America virtually abolished slavery thanks to a variety of “constitutional, judicial or legislative” actions (p. 6). At the same time, in the South, the practices of separation between races intensified.

Along with this, the anxiety of contact meant that in the most racist nuclei of the northern elites, efforts to extend spaces differentiated according to skin color also multiplied. An example of this is the introduction of cars for Black people on trains and the numerous cases of protest and refusal to travel in them (even the great black abolitionist Frederick Douglass was removed from his seat on one occasion for refusing to change cars).

An 1857 court case, Scott v. Sandford (where a slave, Dred Scott, tried to prove that – because he had resided in non-slave states – he should be considered a free man), was to have enormous consequences for the struggles that were to take place a hundred years later and that we know today as the Civil Rights Movement. In the Dred Scott case, which Scott lost, the Supreme Court ruled not only that the plaintiff was not a citizen, but that “Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in the territories”.

In other words, decisions about slavery (and others in this area involving customs) were left to the states and local governments. Another important decision was Hall v. DeCuir (1877) where it was decided that “the laws of a state are not applicable to interstate ship voyages and that only Congress can regulate interstate commerce”. Finally, Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) opened the door for the extension of “segregation of the races, provided the separate facilities were of equal quality.” [ii]

Although protests throughout the century led seven southern states to eliminate laws that favored segregation in the public space, legal decisions such as those mentioned above made possible a reality where supply found its most evident application in Black individuals of high economic capacity .For the same price as their white counterparts, Blacks could travel in a sophisticated train carriage, while in the lower economic strata the difference was perfectly visible in the quality of supply and in the treatment received.

II

Parks’ arrest was followed by a mobilization on her behalf whose movers and shakers included Edgar Daniel (E. D.) Nixon, leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (with whom Parks had worked in the NAACP); Clifford Durr, a white Montgomery lawyer and strong advocate of interracial democracy with his wife Virginia; Jo Ann Gibson, an English professor at Alabama State College; and – among the clergy who offered support – a young pastor, just 26 years old, named Martin Luther King Jr. The success of the boycott, planned to last one day, was such that the organizers decided to extend it, and so it ended up spanning an entire year; along the way, on January 30, 1956, a bomb exploded in King’s house and on February 21 -along with almost 90 protest leaders- he was arrested and charged with having organized a boycott considered illegal. On November 13, the Supreme Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibited racial segregation in interstate as well as intrastate travel, and so, on December 21, 1956, Reverend King “along with several black and white companions boarded a bus for a historic unsegregated ride” (p. 46).

“Parks’ arrest was followed by a mobilization in her favor.”

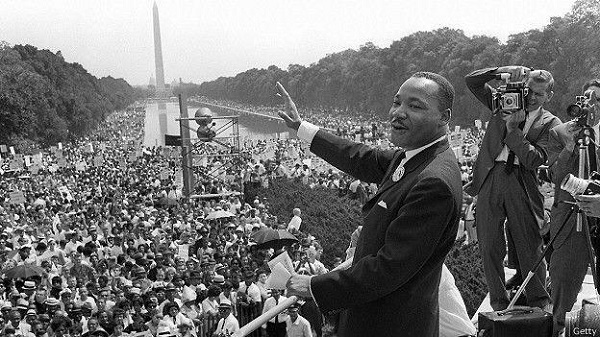

From this point on, the life of Martin Luther King Jr. began to become more risky, complex and to grow into a legend. The son and grandson of Baptist pastors, a pastor himself, MLK developed his political, social, religious and cultural action in the brief period from 1955 to April 4, 1968, the date on which he died in Memphis, assassinated by James Earl Ray, a racist shooter. In this brief period, he became a leading figure in the Montgomery bus boycott (1955-1956); he helped found and was the first president (1957) of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLS); led the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963, where he delivered his famous I Have a Dream speech, recognized as one of the most important pieces of oratory delivered in the country; was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964 and was a leading figure in securing passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In addition, he was the central figure in two of the greatest battles for civil rights: those that took place in the cities of Birmingham and Selma, both in the state of Alabama, in 1963.

III

In the first of these, on April 13, 1963, King was arrested and during the three days he was behind bars he wrote his well-known Letter from Birmingham Jail in which he said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable tissue of mutuality, bound together in a simple fabric of destiny. Anything that affects one directly affects all indirectly.” In that same document, MLK would explain the essence of nonviolence (the Gandhian-inspired mode of protest that he breathed into the Civil Rights Movement) as follows:

Why direct action, sit-ins, marches and the like? Isn’t negotiation a better way? You are exactly right in your call for negotiation. Indeed, that is the purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and establish such creative tension that a community that has consistently refused to negotiate is forced to confront the problem. (…) I have worked and preached vigorously against violent tension, but there is a kind of constructive nonviolent tension that is necessary for growth.[iii] I have worked and preached vigorously against violent tension, but there is a kind of constructive nonviolent tension that is necessary for growth.[iii]

“There is a kind of constructive nonviolent tension that is necessary for growth.”

The condition of nonviolence could only find its foundation in the love that cares for the suffering other and that, as part of God’s created works, even embraces the other who oppresses. Because of this, King’s nonviolence opposes both the part of the Black community that accommodates segregation (be it the lower strata or the academic sectors) and those who preach hatred and separation between the races (which, in context, pointed to the Black nationalists of Elijah Muhammad).

IV

Martin Luther King’s social thought reached its greatest radicalism when, in an endeavor that would bring him multiple misunderstandings (even among leaders of the anti-racist struggles) as well as numerous new enemies (both among whites and Blacks), he became one of the most prominent intellectuals and political figures who publicly opposed the Vietnam War. The statement that gained the greatest resonance in this regard was the speech Beyond Vietnam: The Time to Break the Silence, delivered on April 4, 1967, at Riverside Church before an audience of about 300 people, exactly one year before his death, whose first sentence was: “Tonight I have come to this magnificent house of worship because my conscience leaves me no other choice”, and where he singled out the United States as “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today”. The finesse of the socio-political analysis that MLK was able to develop shines through in excerpts such as the following:

Repeatedly we have been confronted with the cruel irony of watching black and white youths on television screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools. We have seen them in brutal solidarity, burning shacks in a poor village, but we understand that they would never live together on the same block in Detroit. I cannot remain silent in the face of this cruel manipulation of the poor.[iv] Increasingly, by choice or by choice alone, the poor are being manipulated.

Increasingly, by choice or by accident, this is the role our nation has played – the role of those who make peaceful revolutions impossible by refusing to give up the privileges and pleasures that come from the immense benefits of investments across the sea.

I am convinced that, if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we need, as a nation, to undergo a radical revolution of values. We need to quickly begin the transformation from a “things-oriented” society to a “people-oriented” society. When property rights and the profit motive are more important than the person, it is impossible to conquer the gigantic trio of racism, materialism and militarism.[v] (Idem)

V

The other enormous cause to which MLK devoted a great deal of energy was the struggle of American workers for better wages, health care, education for their children, and decent housing. The satisfaction of such demands had to derive, in Luther King’s thinking, from the action of workers integrated into a powerful, organized, highly conscious and nonviolent labor movement; the speech delivered to the Illinois state labor union meeting on October 7, 1965, in Springfield is an illustration of that idea as the following quote shows:

The labor movement was the main force transforming misery and despair into hope and progress. As a result of hard-fought battles, economic and social reforms gave birth to unemployment insurance, age pensions, government assistance for the indigent, and, above all, new standards of living that meant mere survival, if not tolerable living. The captains of industry did not lead this transformation; they held out until they were overrun.[vi]

For Cornel West, editor of the volume The Radical King, MLK’s growing engagement with progressive guild leaders “is integral to his calling”; according to the well-known scholar, poverty was for King not only “a barbaric form of tyranny to be banished from the Earth,” but that “the greatness of nations or civilizations is measured not by military might, architectural prowess, or the number of multimillionaire citizens; the greatness of who or what we rather consist in how we treat the least of these: the weak, the vulnerable, the orphan, the widow, the widow, the stranger, the poor, the marginal, and the prisoner (West, 2014).

VI

“The other enormous cause to which MLK devoted a great deal of energy was the struggle of American workers for better wages, health care, education for children, and decent housing.”

MLK’s last (and unfinished) great battle was the so-called “Poor People’s March” -which sought to repeat the massive demonstration of people in front of the Capitol in Washington, which in 1963 had attracted a quarter of a million people-, but now to demand a fairer redistribution of wealth in the country. In political terms, the most outstanding feature of this new mobilization was that it was intended to convene and represent a multiracial sector which, in addition to Black Americans, was intended to include Native Americans, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans and poor white Americans. Thus, in a speech delivered in New York on March 10, 1968, he was able to say:

Now, I said poor people, too, and by that I mean all poor people. When we go to Washington we are going to have black people with us because black people are poor, but we are also going to have Puerto Ricans because Puerto Ricans are poor in the United States of America. We are going to have Mexican-Americans because they are mistreated. We are going to have Native Americans because they are mistreated. And for those who don’t let their prejudices lead them to blindly support their oppressors, along with us in Washington we’re going to have Appalachian whites (West, 2014).

VII

MLK’s last public speech was the sermon he delivered in Memphis the night before his assassination. Known as I Have Been to the Mountaintop, this beautiful oratorical piece is inspired by the biblical story of Moses (who, after the Exodus, leads the people of Israel to the very Holy Land, although he dies without entering it) to establish a chilling parallel -in light of what was to happen the next day- between the biblical prophet and Martin Luther King himself. Following several investigations and testimonies about those last weeks, the amount of pitfalls, persecution, threats and misunderstanding around MLK damaged his spirit and health, to the point of causing depression and lack of sleep, among other ailments. Some testimonies even speak of the fact that, after years of threat, MLK began to feel, foresee or expect to meet an early death. The speech begins with a strange proposition that the speaker receives from the Almighty himself: to choose the era in which he prefers to live and this, after a long journey through time, turns out to be the one in which we find ourselves. At the end, after mentioning the possible threats to his life, MLK pronounced the following closing paragraph:

We’re going to have some tough days ahead, but I’m not interested in that right now. Because I’ve been to the top of the mountain. And I don’t worry about it. Like anyone else, I’d like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not worried about it now. I just want to fulfill God’s wishes and He has allowed me to climb the mountain. And I’ve looked around. And I have seen the Promised Land. I may not go in there with you, but I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. And I am happy, tonight. I am not worried about anything. I fear no man. My eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord (West, 2014).

VIII

During the funeral of Martin Luther King Jr., following the wishes of his widow, Coretta, excerpts from the sermon entitled The major drum, King delivered on February 4, 1968, at his Ebenezer Church in Atlanta, Georgia, were heard. May these words serve as a farewell:

If any of you are around when it’s my turn to find my day, I don’t want a long funeral. And if you have someone to say the eulogy, tell them not to talk too much. (…)

Tell him not to mention that I have a Nobel Peace Prize, for that is not important.

Tell him not to mention that I have been awarded three or four hundred other recognitions, because this is not important.

Tell them not to mention where I went to school.

But I would like someone to mention that day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to give his life in service to others.

I would like someone to say that day that Martin Luther King Jr. tried to love someone.

I want you to say that I tried to take the right stand on the issue of war. I want you to be able to say that day that I tried to feed the hungry.

And I want you to be able to say that in my life I tried to clothe the naked.

I want you to be able to say that day that I tried to visit those who were in prison.

I want you to say that I tried to love and serve humanity.

Yes, say – if you wish – that I was a drum major; say that I was a drum major for justice.

Say I was a drum major for peace.

I was a drum major for honesty and all the other superficial things won’t matter.

I had no money to leave behind me.

I didn’t have the fine and luxurious things of life to leave behind me.

But I do want to leave a life of commitment and this is all I want to say.

If I can help someone as I pass.

If I can celebrate someone with a word or song.

If I can show someone that their journey is wrong,

then my life will not have been in vain.

If I can do my duty as a Christian,

If I can bring salvation to this world once built,

If I can spread the message as the master taught,

then my life will not have been in vain.

Yes, Jesus, I want to be at your right hand and at your left, But not for any selfish reason.

I want to be on your right and on your left, not in terms of some political kingdom or ambition, but I want to be right there in love and justice, in truth and commitment to others, so that it will make this old world a new world. (Idem)

CITATIONS:

[i] Cianci Salvatore, Susan. Civil Rights in America. Racial desegregation of public accommodations. A National Historic Landmarks theme study. Washington, D. C.: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2009.

[ii] Schultz, David (ed.) Encyclopedia of the Supreme Court. New York: Facts of File, 2005.

[iii] West, Cornel (ed.) The radical King. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014.

[iv] Idem.

[v] Idem.

[vi] King, Jr., Martin Luther. All labor has dignity. Boston: Beacon Press, 2011.

MLK: The Resurrection

MLK, Jr.: The Resurrection

MLK, Jr.: The Resurrection

By David Brooks

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews

The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., during the March on Washington for Work and Freedom, a major demonstration on August 28, 1963, where he delivered his historic I Have a Dream speech. Next Wednesday will be the 50th anniversary of his murder in Memphis,

English Article Goes Here

===

The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. was killed 50 years ago (April 4) in Memphis, marking the bloodiest moment of what would be a 1968 that shook the United States and various parts of the world. Half a century later, this country is in the midst of a reactionary wave that has elevated a white supremacist backed by the Ku Klux Klan to the presidency, almost enough to make fun of King’s famous dream.

But it is worth remembering that King, when he was assassinated, was no longer just the man with a dream of racial equality, but a Nobel Prize winner and international moral authority who had dared in his later years to question and condemn his country’s economic and imperial system, including the war against Vietnam.

King went to Memphis, in the southern state of Tennessee, to support a union garbage workers strike in the name of economic and social justice. At the same time, he was organizing a national mobilization called the Poor People’s Campaign to demand economic rights for the underprivileged of all races and colors, a fundamental change in the U.S. capitalist system.

In the official rites and celebrations that King receives each year, it recalls his famous I Have a Dream speech, which he gave in 1963, but they almost never mention the radical message at the end of his life.

In 1967, King told a civil rights organization that the movement must address the issue of a restructuring of American society as a whole, adding that doing so meant coming to see that the problems of racism, economic exploitation, and war were all linked. These are interrelated evils. On the issue of economic injustice, he did not limit it to a racial issue: Let us be dissatisfied until the tragic walls that separate the outer city of wealth and comfort from the inner city of poverty and despair are destroyed by the battering rams of the forces of justice.

A few months earlier, he commented at a meeting of a civil rights organization: I think it is necessary to realize that we have moved from an era of civil rights to an era of human rights (…) we see that there has to be a radical redistribution of economic and political power…’.

Fifty years later, despite major changes in the country’s laws and regulations around institutional racism, crowned by the election of the first African-American president and what that means in a country founded on the backs of slaves, in essence, little seems to have changed.

An AP/NORC poll last week found that only one in 10 African Americans think the United States has met the goals of the civil rights movement half a century ago (35 percent of whites believe it has) after two rounds by an African-American president.

Fifty years later, new generations are continuing the fight against economic inequality, which has reached a record level in almost a century, with 1 percent of the richest families controlling nearly twice the wealth of 90 percent of the poor.

Fifty years later, incidents of official violence provoke fury. Impunity prevails as before, and indicators of segregation and racism multiply along with, and part of, the official anti-immigrant policies. Not to mention militarism in a country that has been in its longest wars in its history hoping to forget Vietnam.

But in the face of this, 50 years later, King’s echoes are heard all over the country.

Teachers in Oklahoma will begin a strike this Monday, following the triumphant example of their West Virginia peers, demanding not only a living wage and respect for their work – as they did 50 years ago in Memphis – but also greater investment in public education, especially to serve the poor and minorities; their counterparts in Kentucky (where teachers declared themselves sick by closing schools in 26 counties last Friday), Arizona and Wisconsin

African-American Rev. William Barber, famous for his Moral Mondays movement in North Carolina in 2013, which fought state initiatives to reduce spending on education and healthcare and to overturn some electoral rights, is resurrecting King’s Poor People’s Campaign this spring, and declaring, as his predecessor, that this is a moral issue.

Subscribe to Blog via Email

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | |

You must be logged in to post a comment.