The shortest night in the world

Amid gunfire, bombs and with cities surrounded by the Rebel Army, the last day of 1958 in Cuba had an unexpected end for many people.

Author:

Luis Raúl Vázquez Muñoz |digital@juventudrebelde.cu

Published: Thursday 30 December 2021 | 08:34:42 pm. Updated: Friday 31 December 2021 | 12:09:53 pm.

Translated and edited by Walter Lippmann for CubaNews.

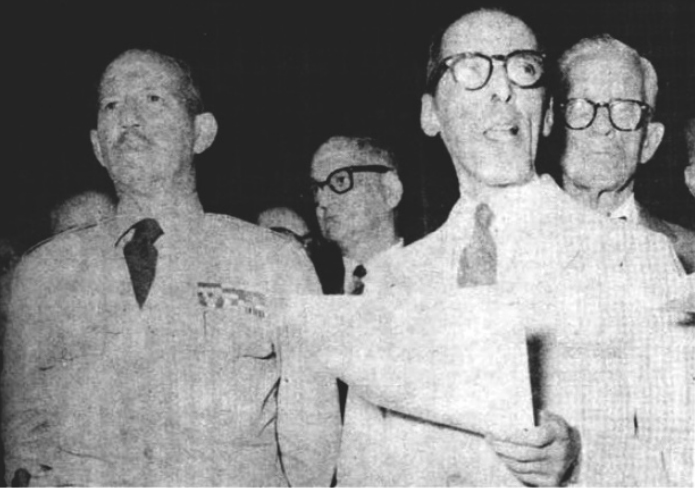

Ambassador Earl T. Smith with Batista. Smiles over, a warning: he could not enter the United States. Author: JR Archive Posted: 12/30/2021 | 07:39 pm

That night of December 31, 1958, journalist Alejandro Vilela slept little. At the edge of dawn, in the middle of the deepest sleep, he was awakened by a phone call. It was his boss, Jorge Bourbakis, the director of Radio Reloj: “Vilela, how are you?”.

The reporter had to take a deeper breath to get rid of the heaviness of rest. Despite the customs of the date, Vilela went to bed early, after playing a game of dominoes at a friend’s house.

It was the end of the year, he had to stay up late until the next morning, but every now and then in the neighborhoods of Havana he heard gunshots or the explosion of a bomb. It was not a festive atmosphere, so he decided to return home. However, all the lethargy disappeared instantly when he heard: “You need to come here”.

The telephones in the CMQ building, where the radio station is located to this day, were tapped by the police. Therefore, those very precise words at that hour of the morning, without providing further details, were a sign that something very big was going on. The definitive certainty, however, came when he pushed open the door of the radio station and found the newsroom turned into a maelstrom.

Magistrate Carlos Manuel Piedra tried to form a government with Cantillo as head of the army. The attempt only lasted a few hours. Photo: Bohemia Archive.

“Vilela,” said Bourbakis, “it seems that Batista is leaving Cuba at this moment. You need to confirm it”. As he attended the police news, Vilela had deciphered the codes of the patrol cars, so he had identified the code number of the vehicles of the main bosses, and with a little attention he could find out what was going on in any place.

He sat down at the receiver and immediately discovered something strange. At that hour the cars of the top brass were reporting from the airstrip of Aerovias Q, a private airline with frequent flights to the United States, located in the area of the Columbia military camp. The voices were nervous, and when a subordinate asked for instructions, his bosses ordered him to interrupt the communication and call immediately by telephone.

Suddenly, an operator made a brief allusion to car one. Vilela frowned: “Car one? Why at that hour was the car at the airport without the trip having been announced?

After 3:00 a.m. the plant fell silent. Only an occasional transmission could be heard, and that silence was great compared to the agitation heard minutes before. Still, one question lingered in the air: if all the bosses went to the airport, why didn’t they report back, as usual?

Vilela turned away from the receiver and as he turned around he saw that everyone in the newsroom was in front of him. Nothing could be heard. With shrugged shoulders, he announced, “Bourbakis, I believe that, indeed, Batista has just left Cuba.”

***

A few hours before, after dinner time, Sergeant Jorge Tasis, from the Investigations Bureau, was driving through the streets of Havana in his Ford Falcon. It was cold and, except for the occasional gunshots heard in the distance, nothing seemed to disturb the officer’s journey.

Suddenly, a sharp order was heard over the radio: “All Bureau cars, report urgently to the post”. Such a call was unusual, and Tasis pushed the car’s accelerator pedal to the metal. In eight minutes he arrived at the headquarters building, at the intersection of 23rd Street and the Almendares River bridge.

The place was a whirlwind, and everywhere there were cars with open doors and armed officers, as if they were going to war, but dressed in civilian clothes. The head of the Information Bureau, Colonel Orlando Piedra Negueruela, appeared with his escort, and at a signal, a caravan of vehicles sped toward the Air Force building at the Columbia military camp.

Piedra got out of the car and walked away from the group. After ten minutes he returned in a stifled state and said, “Only those I mention on this list are coming in with me. The rest of you, go back to your services.” On the list were the main officers who had been singled out for their crimes and were considered the most wanted by the Cuban underground.

Before they went to the airfield, Piedra ordered: “Leave your weapons here”. Tasis was not mentioned, but a colonel named Medina ordered him to enter. On the way to the runway, Tasis heard the sound of two C-54s with their four engines running. They were lit from the inside and with the passenger stairs attached to the doors. Nearby were three other planes with their turbines running. Five minutes later, three cars arrived at full speed and Batista got out of a dark-colored Cadillac. Without stopping, and almost oblivious to the commanding voices of presenting arms, he boarded the first plane, located about 500 meters from the Air Force building. With him were his eldest son, Jorge; his brother-in-law, General Fernandez Miranda, four escorts and an entourage of 36 people.

Already on the last steps, he turned to General Eulogio Cantillo Porras, chief of operations in the East, and said: “Cantillo, call Magistrate Piedra immediately. Call a conference of the press bloc. Communicate with the American Embassy… Do not fail to follow my instructions!”.

Possibly, Tasis could not contain a tingling in his body. Through the second C-54, the head of the army, General Francisco Tabernilla Dolz, entered with his family and about 40 people. At the foot of the stairs everything was agitation and it is possible that the sergeant -like many that night, although in other places in Havana- could not contain some words that tightened in his mind: “But what the hell is happening here?”.

***

Perhaps it all began on December 9, 1958, when Batista received William D. Pawley, former manager of Panamerican Airways in Cuba, at his Kuquine estate. Pawley was his friend and a man who spent part of his childhood on the island.

During the conversation, as if out of the corner of his eye, while they were talking about the situation in the country, the American, also considered a person close to President Eisenhower, suggested to the dictator that he resign and leave with his family for his residence in the United States, in Daytona Beach.

“No one will bother you there,” he insisted. Batista refused. He said that, on his honor, he would remain in power until February 24, 1959, when he would hand over command to President Andres Rivero Aguero, who was elected in a rigged ballot with little participation.

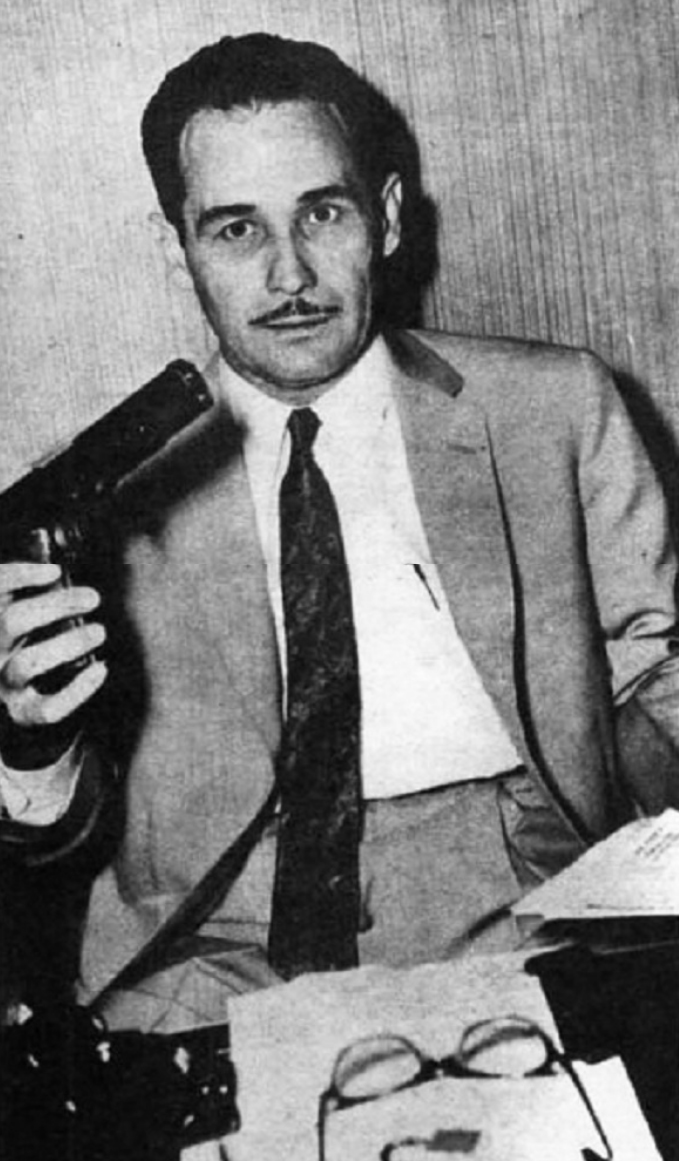

Lieutenant Colonel Esteban Ventura Novo entered the plane where the dictator was fleeing at gunpoint. Photo:JR Archive.

Despite the cordiality, Batista must have felt that that exchange was neither so personal nor so private. And he was not wrong: upon his return, Pawley prepared a note for the State Department in which he referred to everything he had discussed at Kuquine. The tycoon’s report coincided with the report of others, who, under hidden instructions from Washington and with the indication that everything should be seen as a concern of friends, recommended to the dictator the possibility of resigning, but was met at all times with a flat refusal.

The day after Pawley’s visit, the U.S. Ambassador to Cuba, Earl T. Smith, traveled for a meeting with the State Department’s top executives for Latin America. The concern was not only about the present but also about the future.

The intelligence analyses were not favorable, and by the 16th a secret report would circulate in which it was predicted that by December 23rd the Oriente province would be isolated from the country, and its capital, Santiago de Cuba, would be surrounded by the Rebel Army.

The Military Junta or a provisional government was the most favorable option; but Batista had to give up power and he did not want to do so. On the 14th, already in Cuba, Earl T. Smith received a telegram with a clear instruction: he was to inform the dictator that he no longer had the support of the United States.

The message was given in the office of the Kuquine estate, where a solid gold telephone stood out, a gift from the president of Compañía Cubana, a subsidiary of the American giant ITT. With Dr. Gonzalo Güell as a witness, in his dual capacity as Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, Smith conveyed his government’s position. However, the clearest and most terrible point for Batista appeared at the end, when the diplomat warned that his family could, but that he specifically could not enter the United States. “Maybe in six or seven months we could give him the visa,” he said. Maybe…

***

The big game began seven days later. On the afternoon of December 22, 1958, the head of the guard, Colonel Airman Cosme Varas, entered Batista’s private office on the third floor of the Presidential Palace.

“Colonel, locate General Silito for me”, the dictator ordered. That order, which would later be known by Corporal Silverio Hertman, one of the communications operators in the Palace and a collaborator of the 26th of July Movement, was carried out within minutes.

“General Tabernilla is at the Armored Regiment Headquarters and is waiting for the micro, president,” Cosme Varas reported. “Tell him to see me without fail at the residence at ten o’clock,” Batista ordered.

At 10:00 p.m., with Germanic accuracy, Brigadier General Francisco (Silito) Tabernilla Palmero, Batista’s military aide and chief of armored vehicles, entered the mansion of the Columbia military camp. There he received a list. Having listened to the instructions, he quickly went to his office to lock himself in with his assistant, Captain Martinez, who was a typist. The list was retyped to remove names and include others.

Having finished the work in the middle of the night, and agitated by what was coming, he went to the house of his father, General Francisco (Pancho) Tabernilla Dolz, head of the army. As soon as he entered, without much ceremony, he announced, “He is leaving.”

***

The plan of the escape would be two-sided. On the one hand, a firm resolution would be shown. On the other, under the curtain, a coup would be organized in which Cantillo would take command of the army and negotiate with the Rebel Army to gain time and form a government presided over by Dr. Carlos Manuel Piedra, the oldest magistrate of the Supreme Court.

Colonel Ramón Barquín Pérez, who was in prison in Isla de Pinos for having led an attempted rebellion in 1956 under a movement known as Los Puros, would be released at 2:30 a.m., after the dictator’s escape was confirmed. Barquín’s mission would be to take control of the army and the government and stop the Revolution. As part of the plan, on December 28 Cantillo would meet with Fidel in Oriente, with the purpose of organizing an uprising. Batista, of course, would be kept informed of everything.

***

On Wednesday, December 31, 1958, at the stroke of midnight, Batista appeared smiling in the living room of the presidential residence in Columbia. A servant uncorked a bottle of champagne and the dictator raised his glass. “Happy New Year, gentlemen,” he said. “Cheers! Cheers!”

A few minutes later, still in the midst of the greetings, Prime Minister Gonzalo Güell announced, “Mr. President, the Dominicans are waiting.” It was the signal. Batista excused himself and said he would return immediately. Soon after, an assistant colonel approached the president of the Senate, Anselmo Alliegro Milá: “Doctor, the president asks you to come down”. Alliegro thought it was for a few drinks and asked Rivero Agüero to go with him. The military man was polite, but firm: “You alone, doctor”.

When he passed through the anteroom of the office he was dumbfounded: the head of the Military Service, General Perez Coujil, bathed in sweat, had one foot on a suitcase and with the help of several officers, he was trying to close it. The other astonishment was when he entered the office: Batista, surrounded by high-ranking officers and with a violet face, was signing a document.

“Alliegro, these gentlemen have given me a coup d’état!”. The President of the Senate smiled: “Mr. President, you mean a military coup”… “Alliegro, call it whatever you want; but it is a coup and I resign”.

The politician began to breathe in an agitated manner, while General José Eleuterio Pedraza approached him with a mocking gleam in his eye. In one hand he carried a piece of paper and in the other a pen. In his ear, he whispered, “Sign quickly, before the troops find out that this man is leaving.”

A telephone rang. Batista picked it up and immediately hung up. “Good evening, gentlemen,” he said. On his way out he took Andrés Rivero Agüero by the arm. “Let’s go!” he said rudely. The president-elect asked agitated, “Where to?”. “Don’t ask! Abroad! Come with me or they’ll kill you too! Tell your wife!” And he shouted: “Martha, pick up the girl!”.

General Francisco Tabernilla Palmero prepared the list of the escape of December 31, 1958. Photo: JR Archive.

About to take off, a fight was heard at the door of the plane. Captain Alfredo J. Sadulé, the military aide in charge of controlling the entrance, was struggling with Lieutenant Colonel Esteban Ventura Novo, chief of the Fifth Police Station and one of the biggest murderers in the country. Ventura had been left off the list and was trying to enter at gunpoint. “Nobody keeps me from getting on board!” he shouted. Batista let him in.

At that moment, while the plane was on its way to the Dominican Republic, in Yaguajay, Captain Alfredo Abon Lee was enduring a strong siege led by Commander Camilo Cienfuegos. In Santa Clara, the forces of the Leoncio Vidal regiment began to be surrounded by the guerrillas led by Ché in the middle of a city full of gunpowder smell and overshadowed by the black smoke of the bombings. In the Oriente, Fidel surrounded Santiago de Cuba and the city was kept on tenterhooks waiting for the combats. In Guantánamo, Raúl was finalizing the details for the final assault on the city.

In the dungeons of the dictatorship, the fresh blood and screams of the tortured could be felt, even with the New Year’s Eve festivities, and on the Columbia airstrip, as far as the eye could see, a forest of suitcases and abandoned cars could be seen in the coldest and shortest night in the world. The war in Cuba was over. It was January 1, 1959.

Sources consulted:

Álvaro Prendes Quintana: Prologue for a battle.Editorial Letras Cubanas, Havana, 1988.

Mario Kuchilán Sol: Fabulario. Huracán Publishing House, Havana, 1972.

Bohemia, special edition of Libertad, January 1959.

Norberto Fuentes: El compañero Silito, in Libreta de Apuntes, blog by Norberto Fuentes, January 20, 2015.

Alejandro Vilela: Batista’s escape from Cuba: Radio Reloj was the first to confirm the tyrant’s flight. In Cubadebate, Wednesday, August 5, 2009.

Documents on the fall of the Batista government, November-December 1958. U.S. Department of State, Bureau of History. Https://history.state.gov/

Texts by Ciro Bianchi published in Juventud Rebelde

You must be logged in to post a comment.