Jon

Hillson 1949-2004

Selected writings by and about Jon Hillson

Jon

Hillson spent his entire adult life active in the struggle for a better

society, a socialist society. We first met in the 1970s, when we were both

members of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States. He was a

journalist, a trade unionist and a revolutionary socialist activist. Here

you will find a broad selection of Hillson's writings, and of the many tributes to and observations

which have come out about his life and activities.

Jon

Hillson spent his entire adult life active in the struggle for a better

society, a socialist society. We first met in the 1970s, when we were both

members of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States. He was a

journalist, a trade unionist and a revolutionary socialist activist. Here

you will find a broad selection of Hillson's writings, and of the many tributes to and observations

which have come out about his life and activities.

Many of Hillson's years were devoted to a tireless defense of the Cuban

Revolution. He had many other interests as well. Cuba was the central

focus of his work in recent years as most of the linked messages below

make clear.

Please send additional ones to:

walterlx@earthlink.net

Thanks!

Walter Lippmann,

March 2006

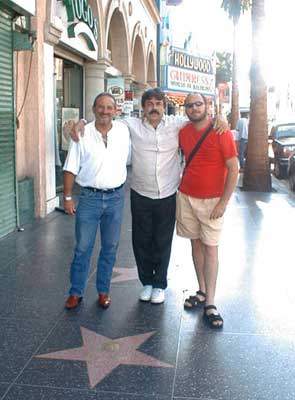

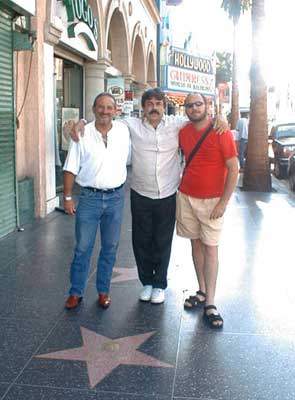

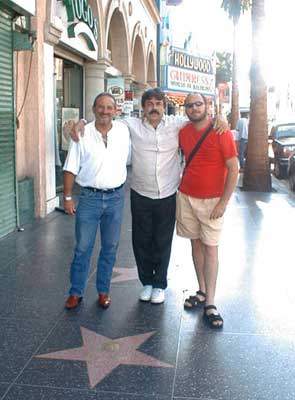

Jon Hillson at a Cuba solidarity meeting

held in Los Angeles, California 2001.

Photo by Walter Lippmann

|

Tributes to Jon

Hillson

|

|

John

Johnson, Los Angeles, California

|

|

Walter

Lippmann, Havana, Cuba

|

|

Karen

Lee Wald, San Jose, California

|

|

CISPES

Los Angeles, California

|

|

Chuck

Anderson, Anaheim, California

|

|

Harry

Nier, Denver, Colorado

|

|

Jose

F. Charon B, Havana, Cuba

|

|

Cal

State

LA Latin American Society

|

|

Fred

Feldman, New York City

|

|

Eric

Gordon, Los Angeles, California

|

|

Robin

Maisel, Waco, Texas

|

|

Paula

Solomon, Los Angeles

|

|

Lisa

Valanti, US-Cuba Sister Cities Association

|

|

Nelson

P. Valdes, Albuquerque, New Mexico

|

|

Jim

Smith, Venice, California

|

|

Cuban

Inst. for Friendship with the Peoples (ICAP)

|

|

Arleen

Rodriguez , En Memoria de Jon Hillson

|

|

Arleen

Rodriguez, In Memory of Jon Hillson

|

|

Louis

Proyect, New York City

|

|

Sandra

Levinson, New York City

|

|

Ike

Nahem, New York City

|

|

Fred

Burks, Berkeley, California

|

|

Granma

Diario (Spanish)

|

|

Mi

Socio de la Yuma (La Jiribilla)

|

|

Breve

biografia de Jon Hillson

|

|

Los

Angeles "Right to Travel" Forum (The Militant)

|

|

CubaNow

digital magazine

|

|

Jose

G. Perez

|

|

National

Comm. to Free The Five |

|

Jon

Hillson: The American Friend (CubaNow) |

|

Paula

Solomon: My Friend Jon

|

|

John

Johnson on the memorial meeting

|

|

National

Network on Cuba

|

|

Stan

Smith (Chicago)

|

|

Barry

Schier (Los Angeles)

|

|

Barry

Schier (Continued)

|

|

Steve

Eckardt and others

|

========================================

MY

BUDDY FROM la YUMA

("La Yuma"

is Cuban slang for the United States)

His writing was a political weapon, a means

to reach and mobilize the workers, of creating

their consciousness. I saw him

write several

times and he took on this task as if he had an

urgent need to bring out that part of the

US reality that the great mass media and,

of course, Hollywood silenced.

by M. H. Lagarde|

La Habana

From left to right: Jon Hillson,

From left to right: Jon Hillson,

Rolando Pérez

Betancourt

y M. H. Lagarde

Recently

arriving at the First Meeting of Cuban Venezuelan writers in

Caracas

I received terrible news:

Jon Hillson had died.

First

I thought that it was a joke in bad taste and to confirm what was still

unbelievable I questioned, via e-mail, several common friends. All

of a sudden the phone rang and I recognized the voice of Hilda, a Salvadoran who

lived in Los Angeles. “Yes,

It’s true, she assured me, Jon is dead”.

She told me that when she was participating in a Solidarity with Cuba

event someone said: “It is a

shame Jon is not here with us”: “And

where is he?” she asked, thinking that Hillson

was on one of his trips he used to make to support some strike or protest of the

US workers. But the person she was

talking to said that Jon had died a few hours ago of a sudden heart attack.

Hilda explained more: Hillson was preparing

a barbecue for an act in defense of the Cuban Revolution.

He had gone to the market to buy some chickens and on his way to the

parking lot where his modest convertible VW was parked, he fell to the floor.

There is no doubt that La Jiribilla has lost its best collaborator, the Cuban

Revolution one of its most faithful defenders in the US and I -- who doesn't

have many -- my buddy from La Yuma.

I met Hillson in September, 2001, due to the trip of

the Cuban delegation of musicians to the Latin Grammy that would be held in Los Angeles. Before

leaving, I had written him an e-mail saying that in a few days we would be in

that city and that, of course, I counted on his help.

In response, Hillson, whom I had never met

– merely read his chronicle on Reynaldo Arenas – answered something like

“Not to worry, My house is your house”.

I saw him for the first time in one of the exits of the Los Angeles

airport. He

was of medium height, gray hair and appeared to be in his forties.

His earring, four days beard, his sandals, shorts and bleached T-shirt,

did not give the appearance of the bespectacled professor that, in my

imagination, was the author of that objective and serious essay on homosexuality

in the Cuban Revolution.

The coordinator of the Solidarity with Cuba Coalition of Los Angeles was

standing among many

US

friends of

Cuba

who held up posters demanding an end to the

blockade and Cuban flags. In Los Angeles accented Spanish he said words of welcome to the

brother and sister artists of the

Island

who had just arrived in the

US

in spite of the strong pressure of the Miami

Mafia to prevent it.

Luckily for Rolando Pérez

Betancourt, the Granma critic and

journalist. who

was also reporting the event and me, Hillson and his

kind wife, Beverly, offered to serve as guides around

Los Angeles.

At

times, Jon had a shift in the airport where he worked as a porter and then

Beverly

was the driver.

But every spare moment Jon had he would show up early at our hotel room.

That is what happened that

September 11, 2001. While

Rolando and I were watching the television, surprised and in disbelief, as each

of the twin towers of the

World

Trade

Center

crumbled, Hillson

arrived. Like everyone in Los Angeles

– the city was paralyzed and the congested

avenues suddenly became an asphalt desert – we spent the whole morning

commenting on the events. Jon did

not seem too affected by the images of the planes crashing into the skyscrapers

or of the people jumping out into space to escape the flames and, every once in

a while, he would make a call on his cell phone or compare opinions with us.

The three agreed that, undoubtedly, those images taken from a film of the

worst

Hollywood

style marked the beginning of a new imperial era.

“The Americans – I said –, in vengeance are going to ravage other Guernicas

in the world”. Hillson, for his part, forecast the

so-called Patriot Act and noted that the attack in

New York

would serve as a pretext to curb the struggle for

workers’ rights and other civil rights.

After spending the whole afternoon speculating on the possible persons

responsible for the crime against the towers we concluded that, neither the

Palestinians -- the first accused, according to the false television images that

showed some children jumping for joy -- nor the backward Arab nations had

anything to do with such a carefully-planned terrorist operation.

Hillson

invited us for dinner. With Beverly

and two other Ecuadorian friends, we crossed the ghost city of

Los Angeles

to

Santa Monica

Beach. In

a Mexican restaurant on the pier that extends over the Pacific, our conversation

took other turns and Hillson talked of several

historical and political subjects on which he proved to be very well informed.

Jon was more than a porter and union leader of the

Los Angeles

Airport

. One

of the days, when we visited him at home in the Inglewood neighborhood, commenting on his magnificent essay

on Reynaldo Arenas, I asked him: “Why

don’t you work for a newspaper?”.

“And do you think that with my ideas they are going to let me write

anywhere”, he answered. He was

right, in part, but apart from the obvious censure, the real cause that a man of

his intellectual capacity would work as porter in the airport was due to his

union activism that was like a religious mission.

“A true militant – he told me once while we ate in my home in

Havana

– should work at the base”.

For this reason he had worked many years in a textile factory.

He was proud of being a worker. In

two conferences he gave to young Cuban persons on the reality of the US, I presented him as an intellectual who

collaborated with La Jiribilla.

But whenever he spoke he first pointed out

that, for him, his greatest virtue was his proletarian condition.

At the same time he was not one of those purists who use a word for its simple

esthetic quality. His writing was a

political weapon, a form of reaching and mobilizing the workers, of making them

become aware. I saw him write

several times and he did it as if he had an urgent need to bring up that part of

the

US

reality that the great mass media and, of course,

Hollywood

silenced.

We often asked ourselves in La Jiribilla

how that man could fulfill his work hours in the airport, how he could write

those long reports that he always sent, almost always, at the critical hours of

closing. According to his stories,

he visited several cities in the span of a week.

He seemed to be several places at the same time.

At times, it is true, his texts, primarily those of union matters,

covered much more than the political or cultural subjects of the editorial line

of the magazine. However, you did

not need to be well informed to realize that Hillson

wrote about something totally new. His

reports about the struggles of the US workers, at least in Spanish, were unique.

He reported of the most recent

US workers movement in a language that was not

native to him.

Beverly

had introduced him to the secrets of Spanish

during the Sandinista Revolution.

Instead of the professor I expected to find upon my arrival to Los Angeles, Jon, the journalist did not wander about nor

change the meaning of words. Since

he was an unpretentious intellectual, he called things by their name.

The class struggle was simply that and the main protagonists of his

stories were the workers and the capital bourgeoisie, humanity and the empire,

justice and injustice, truth and lie. In reality it was lucky for any magazine

to count with a collaborator like Hillson.

We never paid him a cent. He

wrote simply out of his faith that his charges could help to improve the world.

Under these same principles, the defense of Cuba

had a special place.

Hillson, since his studies in junior high

during the 60s in the

New York

suburbs, had become a political activists and a

strong supporter of the Cuban Revolution after reading the essay by Che

Guevara: Man and Socialism in

Cuba.

Cuba not only appeared in his articles or constant

activities he organized in

Los Angeles

in favor of the

Island, but his examples served his mission as a union

activist in the airport. He always

had

Cuba

present in his union speeches that his comrades

use to jibe him with “Be quiet, Fidel!”

Be quiet, Cuban!” Always

at the service of the Revolution, his latest activities were in the struggle for

the freedom of the Five Cuban heroes, prisoners of the empire, as well as, for

the rights of the

US

citizens to travel to the

Island

.

His last visit to

Havana

was as the organizer of a delegation of one

hundred US

youths eager to learn for themselves,

about the Cuban reality.

The

last time we met was at the entrance of the Palacio del

Segundo Cabo. “When

you return – I said in leaving – we will go with

Beverly

to the carnivals”.

“I don’t like them”, he explained.

“You will – I insisted – just wait and see”.

About a week before his death, two days before my departure for

Venezuela, he called me up as he was used to doing every

Friday, to ask me if I had read the e-mail he sent with some of his comments on

the liberal intellectuality of the United Sates.

I had not had time to read it but, nonetheless, we spoke for 20 minutes

about the coming elections, the possible Democratic candidates and the event he

was preparing to fight the new restrictions of the present administration to

prevent travel to Cuba. He

said he would participate in an act where Bush’s Thai translator, recently

penalized for traveling to the

Island

, would speak.

“A good guy”, he added. He

also mentioned a protest that would be the largest of all time in Los Angeles and where, somehow,

the Five would be present. As

usual, I asked him to send a good article on all of that.

Later, I asked when he planned to return.

“By the end of March, he said, I’ll go with the last delegation to

travel with a license.

His death prevented his return on that date.

But if, as I believe, Jon Hillson is reading

these lines somewhere, he knows as well as I that he will return again to the

island the day that the barriers of deceit are no longer

an obstacle to the friendship between our two peoples.

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF JON HILLSON

He was a political activist since 1965, when he was in junior high school in the

New York suburbs. At that time he began to participate in the movement against

the war in Vietnam and for the civil rights of black people. He was also a

radical student leader at Colorado University where he was the director of the Colorado

Daily, a politically-influential newspaper favoring the development of

the Chicano nationalist movement. He became a passionate supporter of the Cuban

Revolution after reading an essay by Che Guevara: Socialism and Man in

Cuba.

Later he joined the Young Socialist Alliance and was a member of its national

committee. He participated as an activist and journalist in the last battle of

the movement for civil rights in Boston (1974-1976) for equality in the public

education system and wrote The Battle of Boston, a book that was

published by Pathfinder Press.

He participated in the defense of the Sandinista popular revolution as a union

activist in a textile factory and led three contingents of US citizens to work

in the coffee bean harvest in the Nicaraguan mountains. He gathered and edited a

leaflet in 1987 on the continuity of the Sandinista Revolution what was

published by the New Central American Institute. As a textile union leader he

organized protests against the first war in the Persian Gulf. He was a picket

captain in the Canadian Pacific/Soo Line railroad strike in 1974, the longest

in the past 26 years and was candidate for governor of Minnesota for the

Socialist Workers Party.

For years, Hillson wrote articles on a variety of subjects for national and

international publications. Some were: American Writer, Barricada

International, Central American Reporter, Change-Links, CubaNow [digital

magazine], Granma, The Guardian, The Militant, Juventud Rebelde, La

Jiribilla, La Opinion, NY Transfer News, Reporter on the Americas, Seeing Red,

Ventana, and other publications. He is the author of The Sexual

Politics of Reinaldo Arenas: Reality, Fiction and the Real Record of the Cuban

Revolution which has been read by thousands of people in Internet

versions in several languages in North America, Europe and Australia.

Hillson, who was coordinator of the Coalition in Solidarity with Cuba in Los

Angeles, helped organize several delegations of hundreds of persons to visit to

Cuba to collaborate with the Cuban youth. Due to his efforts,, thousands of

people from Los Angeles heard many representatives of the Cuban Revolution on

tours organized by the Coalition in Solidarity with Cuba of Los Angeles,

California.

Before his death, a tireless leader for workers' rights, he was a member of the

International Association of Machinists (IAM) (and was a ramp worker at Los

Angeles International Airport where he promoted the example of Cuba among his

workmates.

He was an invaluable collaborator of La Jiribilla where he published a weekly

column, Notes from the North, an updated and detailed analysis of US reality.

His death caught him at a time when he was preparing what was, undoubtedly, one

of his great passions, an event in defense of the Cuban Revolution.

(Translated from La Jiribilla for CubaNews by Ana Portela.)

http://www.lajiribilla.cu/2004/n144_02/144_32.html

==========================================

February 12, 2004

The American Friend

By

Rolando Peréz Betancourt

Jon Hillson and Beverly, his wife and

Jon Hillson and Beverly, his wife and

collaborator, at

their house in Los Angeles

M.H.

Lagarde tells us, in his great piece in La Jiribilla, that while

Jon Hillson watched the fateful events of September 11, he predicted the renewed

will of the U.S. administration to dominate the world.

With the serene insight of a prophet of doom, he forecast almost all that would

now follow, from wars to the repressive role of the government against U.S.

society. At the time, three days after the event, it was easy to see that Jon

was one of those simple men whom life has made a personality.

He

had appeared and made his dynamic mark that night in September when a Cuban

delegation to the Latin Grammys arrived in Los Angeles, after a change of venue

as a result of threats by the hard-line Miami right. Heading a welcoming group

with signs and cheering Cuba, he spoke warm words and clearly stated that at not

time were the Cuban to be left alone. That's the way it was. As the coordinator

of the Los Angeles Coalition in Solidarity with Cuba, he became indispensible.

He organized events, good food and cooks for those meetings. And the next day he

was back at work at the airport ramp, carrying baggage. And from that he ran in

each time for the welcome.

On September 10, days before the Grammy awards that would eventually be cancelled,

Jon Hillson took Lagarde and this author to the site of the planned ceremony to

explain where the stubborn people of Cuban origin, opposed to the presence of

artists from the island (as they had announced to the press) would be standing.

He further explained where the members of the Coalition in Solidarity with Cuba

would be. Looking taller in his cowboy boots and earing, and with a broad smile,

he said, "of course, we are going to win."

On

the 12th, in view of the grief gripping Los Angeles, Jon proposed hopping over

to Hollywood. The mecca also seemed terrified with only a few tourists in the

streets and a flickering image of Marilyn Monroe dressed in black, looking up at

the sky most of the time - as if expecting something terrible - and with no wish

to earn a few dollars, as a lady-in-waiting for the photographers.

In Hollywood, Jon Hillson demonstrated that he knew as much about films as he

did about politics and ideologies. Since his youth, back in the golden sixties,

against the Vietnam war, he committed himself to the cause of the humble and

embraced Marxmsm as the best basis to become an active anti-imperialist in his

country. It was a long, hard struggle for which he prepared himself with

enviable fortitute. Without giving up his hard work, years as a textile worker,

days of dedication and dsily studied changed the worker into the solid

intellectual he always denied being. (I was able to browse through his books

scattered helter-skelter in the inglewood garage that was his office.)

In his column, Notas del Norte (Norte from the North), published

in La Jiribilla, he gave proof of the persevering clarity and

excellent style which was also seen in his articles and small news items which

were published in Juventud Rebelde and Granma. Other

publications in the world knew of Hillson's free collaboration. He also

published essays on different subjects and a book. Always defending the Cuban

Revolution, in recent years he traveled to cuba with groups of students from the

United States. He cleared the way in his country so that voices could be heard

of the hidden truth behind the imprisonment of our five companeros.

JON HILLSON WAS TIRELESS

Just a few days ago, while walking to his car after making some arrangements

to hold a Solidarity with Cuba event, his still-young heard played a dirty trick

on him.

Personally, I will always remember him with his impish smile, that September

night in 2001, when he took us to the Los Angeles Observatory [in Griffith Park]

where the high point of Rebel Without A Cause was filmed. After

talking for a long time about James Dean and the importance of this film for its

time, we silently looked up at the sky, for the first time in many years without

criss-crossing planes, watching from that height as the stars shown large and

eternal.

Translated

for CubaNews by Ana Portela from the original:

http://www.granma.cubaweb.cu/2004/02/12/cultura/articulo08.html

El amigo americano

ROLANDO PÉREZ BETANCOURT

Como cuenta M.H. Lagarde en un formidable trabajo

aparecido en la edición electrónica de La Jiribilla, el mismo 11 de septiembre

del 2001, de pie frente al televisor de la habitación del hotel de Los Ángeles

que reproducía las imágenes del derrumbe de las Torres Gemelas, Jon Hillson

predijo buena parte del vuelo dominador de mundos que desde entonces renovaría

con mayor vigor la Administración norteamericana.

Jon

Hillson y Beverly, su esposa y

Jon

Hillson y Beverly, su esposa y

colaboradora, en su casa de Los Ángeles.

Con los tonos de un sereno agorero, anunció casi

todo lo que vendría, desde las guerras hasta el papel represivo del Gobierno en

contra de la sociedad norteamericana. Ya para entonces, con solo tres días de

haberse presentado, no resultaba difícil barruntar que Jon era uno de esos

hombres simples a los que la vida convierte en personajes.

Había aparecido con su impronta dinámica aquella

noche de septiembre en que la delegación cubana a los Premios Grammy latinos

llegaba a Los Ángeles tras el cambio de sede ocasionado por las amenazas del

Miami recalcitrante. Al frente de un grupo de bienvenida que alzaba cartelones y

daba vivas a Cuba, pronunció unas calurosas palabras y dejó claro que en ningún

momento los cubanos estarían solos. Así fue. Como coordinador de la Coalición de

Solidaridad con Cuba en Los Ángeles, se convirtió en un imprescindible.

Organizaba actos, hablaba en ellos, buscaba comida y cocineros para aquellos

encuentros. Y al otro día a trabajar en la rampa del aeropuerto, en la que

cargaba equipajes y desde donde había tenido que correr la noche de nuestra

llegada para llegar a tiempo a la bienvenida.

El 10 de septiembre, el día anterior de la entrega

de los Grammy, que finalmente sería suspendida, Jon Hillson llevó a Lagarde y al

autor de estas líneas frente a la edificación donde tendría lugar la ceremonia

para explicarles dónde estaría situado el grupito de obcecados de origen cubano

que se opondría a la presencia de los artistas de la Isla (según lo anunciaran

en un periódico), y en qué lugar se situarían los miembros de la Coalición de

Solidaridad con Cuba. Luciendo más alto desde sus botas de cowboy, un pendiente

en la oreja izquierda y a flor de labios su inefable sonrisa, dijo: "Por

supuesto que vamos a ganar".

El día 12, ante el aspecto de desolación que ofrecía

la ciudad de Los Ángeles, Jon Hillson propuso dar un brinco hasta Hollywood.

También la Meca parecía estar aterrorizada con solo unos cuantos turistas en las

calles y una trémula copia de Marilyn Monroe vestida de negro, la mayor parte

del tiempo mirando ella hacia el cielo —como si esperara algo terrible— y sin

ningún deseo de ganarse unos dólares en función de dama de compañía frente a las

cámaras fotográficas.

En Hollywoood, Jon Hillson demostró que sabía tanto

de cine como de política e ideologías. Porque desde muy joven, allá en sus

dorados sesenta en contra de la guerra de Viet Nam, se había comprometido con la

causa de los humildes y abrazó el marxismo como la mejor vía para convertirse en

un activo antimperialista en su tierra. Una larga lucha para la que se preparó

con envidiable empeño. Sin dejar de trabajar en duras faenas —años como obrero

textil—, aquellos días de dedicación y los estudios que a diario hacía (tuve la

oportunidad de curiosear en sus libros en el algo revuelto garaje de Inglewood

convertido en oficina) hicieron del trabajador el sólido intelectual que siempre

negó ser.

En su columna Notas del Norte, publicadas en La

Jiribilla, dejó constancia de la lucidez y del excelente estilo que resaltan

igualmente en artículos y hasta en acontecimientos de corte noticioso publicados

en Juventud Rebelde y Granma. Otras publicaciones del mundo conocieron de

la colaboración gratuita de Hillson, quien también publicó ensayos sobre

diversos temas y un libro. Desde siempre fue un defensor de la Revolución cubana

y, en los últimos tiempos, viajó a Cuba con estudiantes norteamericanos y abría

caminos en su tierra para que pudieran llegar voces que hablaran de la verdad

oculta tras el encarcelamiento de los cinco compañeros nuestros.

ERA UN INCANSABLE JON HILLSON

Hace unos pocos días, mientras caminaba hacia su

auto después de hacer unos preparativos para celebrar un acto de solidaridad con

Cuba, su todavía joven corazón le jugó una fatal trastada.

En lo personal, siempre lo recordaré con su sonrisa

de muchacho pícaro, la noche de septiembre del 2001 en que nos llevó al

observatorio de Los Ángeles donde en los años cincuenta se filmara una escena

cumbre de Rebelde sin causa. Y luego de hablar largo sobre James Dean y

la significación que para la época tuvo el filme, nos quedamos un rato en

silencio en el mirador, contemplando un cielo por primera vez en largos años sin

aviones, y las estrellas, principalmente las estrellas, que desde aquellas

alturas se hacían más grandes y eternas.

http://web.archive.org/web/20040404144341/http://www.granma.cubaweb.cu/2004/02/12/cultura/articulo08.html

MI SOCIO DE LA YUMA

Su

escritura era un arma política, una forma de llegar y movilizar a los

trabajadores, de crearles conciencia. Lo vi escribir varias veces y lo hacía

como si tuviese una necesidad urgente de sacar a flote aquella parte de la

realidad norteamericana que los grandes medios y, por supuesto Hollywood,

silencian.

M. H.

Lagarde| La Habana

• Breve

biografía de Jon Hillson

De

izquierda a derecha, Jon Hillson, Rolando Pérez Betancourt y M. H. Lagarde

De

izquierda a derecha, Jon Hillson, Rolando Pérez Betancourt y M. H. Lagarde

Recién

llegado del Primer Encuentro de Escritores Cubanos Venezolanos que tuvo lugar en

Caracas, encontré un correo con la infausta noticia: Jon Hillson ha muerto.

Al

principio pensé que se trataba de alguna broma de mal gusto y para confirmar lo

que aún me resulta inconcebible me dediqué a indagar, vía email, entre varios

amigos comunes. De pronto, sonó el teléfono e identifiqué la voz de Hilda, una

salvadoreña que reside en Los Ángeles. “Es cierto, aseguró, Jon ha muerto”.

Según contó, ella estaba en un acto de solidaridad con Cuba cuando alguien dijo:

“Es una pena que Jon no esté con nosotros” “¿Y dónde está?” preguntó, creyendo

que Hillson andaba en uno de esos viajes que solía realizar para apoyar alguna

huelga o manifestación de la clase obrera norteamericana. Pero su interlocutor

le respondió que, hacía solo unas horas, Jon había muerto de un repentino ataque

cardiaco. Hilda me especificó aún más: Hillson preparaba una barbacoa para una

actividad en defensa de la Revolución cubana. Había ido al mercado a comprar

unos pollos y al salir del establecimiento, camino al parqueo donde se

encontraba su modesto VW descapotable, se desplomó en el suelo.

No cabe

duda de que La Jiribilla ha perdido al mejor de sus colaboradores, la Revolución

Cubana a uno de sus más fieles defensores en los EE.UU. y yo —que no tengo

muchos, por cierto— a mi socio de la Yuma.

Conocí a

Hillson en septiembre de 2001 a propósito del viaje de la delegación de músicos

cubanos a la premiación de los Grammy Latinos que se celebraría en Los Ángeles.

Antes de partir, le había escrito un correo diciéndole que en pocos días

llegaría a esa ciudad para cubrir para La Jiribilla el evento y que, por

supuesto, contaba con su ayuda. Por la misma vía, Hillson, a quien nunca antes

había visto —sólo había leído su conocido ensayo sobre Reynaldo Arenas—, me

respondió algo así como que me despreocupara: “Mi casa es tu casa”.

Lo vi por

primera vez en una de las salidas del aeropuerto de Los Ángeles. Era un hombre

de mediana estatura, cabello entrecano, que aparentaba unos cuarenta y tantos

años. El zarcillo que llevaba en una oreja, la barba de cuatro días, sus

sandalias, el short y camiseta desteñidos, nada tenían que ver con el

catedrático de espejuelos y levita que, en mi imaginación, debía ser el autor de

aquel objetivo y serio ensayo sobre la homosexualidad en la Revolución cubana.

El

coordinador de la Asociación de Solidaridad con Cuba en Los Ángeles estaba de

pie ante una docena de amigos estadounidenses de Cuba que portaban carteles en

contra del bloqueo y banderas cubanas, y pronunciaba, en su español angelino,

una arenga de bienvenida a los hermanos artistas de la Isla que, a pesar de las

muchas presiones de la mafia de Miami para impedirlo, acababan de arribar a los

EE.UU.

Para

suerte de Rolando Pérez Betancourt, el crítico y periodista de Granma que

también reportaba el evento, y mía, Hillson se brindó, junto a su esposa, la

amable Beverly, para servirnos de guía por Los Ángeles. A veces, Jon tenía turno

en el aeropuerto donde trabajaba como maletero y entonces ella nos servía de

chofer; pero siempre que Jon tenía un rato libre se aparecía temprano en nuestra

habitación del hotel.

Así

ocurrió aquella mañana del 11de septiembre del 2001. Mientras Rolando y yo

contemplábamos en la pantalla del televisor, entre sorprendidos e incrédulos,

desmoronarse una y otra vez las torres del World Trade Center, llegó Hillson.

Como todo el mundo en Los Ángeles — la ciudad se paralizó y las congestionadas

avenidas de repente se transformaron en señalizados desiertos de asfalto—

pasamos la mañana entera comentando lo sucedido. Jon no parecía muy afectado por

las imágenes de los aviones estallando contra los rascacielos o de las personas

lanzándose al vacío para escapar de las llamas y, de vez en cuando, realizaba

una llamada por su celular o confrontaba con nosotros sus criterios. Los tres

coincidimos en que, sin duda, aquellas imágenes sacadas de algún filme del peor

Hollywood, marcaban el inicio de una nueva era imperial. “Los americanos —dije—,

en venganza, van a arrasar con alguna que otra Guernica del mundo”. Hillson por

su parte, como si presagiara el decreto de la llamada Acta Patriótica, apuntó

que el atentado de Nueva York serviría como pretexto para frenar la lucha por

las reivindicaciones de los trabajadores y otros derechos civiles.

Después de

pasar toda la tarde especulando sobre los posibles ejecutores del crimen de las

torres, concluimos que ni los palestinos —los primeros acusados según unas

falsas imágenes de televisión que mostraban a unos niños saltando de regocijo—,

ni los atrasados países árabes, tenían nada que ver con una operación terrorista

tan meticulosamente planificada.

Hillson

nos invitó a cenar. Junto a Beverly y otros dos amigos de origen ecuatoriano,

atravesamos en sendos autos parte de la fantasmagórica ciudad de Los Ángeles

hasta la Playa de Santa Mónica. En un restaurante mexicano situado en la punta

del muelle que se extiende sobre el Pacífico, la conversación tomó por otros

rumbos y Hillson abordó varios temas históricos y políticos sobre los que

demostró tener una vasta cultura.

Jon era

algo más que un maletero y dirigente sindical del aeropuerto de Los Ángeles. Por

esos días, en una ocasión que vistamos su casa en el barrio de Inglewood,

mientras comentaba su magnífico ensayo sobre Reynaldo Arenas, le pregunté: “¿Por

qué no trabajas para algún periódico?” “¿Y tú crees que con mis ideas me a van a

dejar escribir en alguna parte?”, respondió. En parte tenía razón pero, más allá

de la consabida censura, la verdadera causa de que un hombre de su capacidad

intelectual trabajara como maletero en el aeropuerto se debía a que asumía su

quehacer de activista sindical cual una suerte de misión religiosa. “Un

verdadero militante —me dijo una vez mientras comíamos en mi casa en La Habana—,

debe trabajar en la base”. Por esa razón había trabajado también durante muchos

años en una fábrica textil. Vivía orgulloso de ser un obrero. En dos

conferencias que impartió ante jóvenes cubanos sobre la realidad en los EE.UU.,

lo presenté como el intelectual norteamericano que colaboraba para La Jiribilla.

Pero él nunca comenzaba a hablar sin anteponer la aclaración de la que era, para

él, su mayor virtud: su condición proletaria.

Al mismo

tiempo, tampoco era uno de esos escritores puros que abordaba la palabra por

simple pretensión estética. Su escritura era un arma política, una forma de

llegar y movilizar a los trabajadores, de crearles conciencia. Lo vi escribir

varias veces y lo hacía como si tuviese una necesidad urgente de sacar a flote

aquella parte de la realidad norteamericana que los grandes medios y, por

supuesto Hollywood, silencian.

En La

Jiribilla muchas veces nos preguntábamos cómo era posible que aquel hombre, que

tenía que cumplir con un horario de trabajo en el aeropuerto, pudiera escribir

aquellos largos reportes que casi siempre enviaba a la crítica hora del cierre.

Según sus relatos visitaba, en una misma semana, varias ciudades diferentes cual

si poseyese el don de la ubicuidad. A veces, es cierto, sus textos,

principalmente los de carácter sindical, se iban más allá de los temas políticos

o culturales de la línea editorial de la revista, sin embargo no había que estar

muy informado para darse cuenta que Hillson escribía sobre algo totalmente

inédito. Sus crónicas sobre las luchas de los trabajadores norteamericanos, por

lo menos en español, eran únicas. Reportaba la historia más reciente del

movimiento obrero norteamericano en un idioma que no dominaba completamente.

Beverly lo

había iniciado en los secretos del castellano en los días de la Revolución

sandinista.

A

diferencia del profesor que yo esperaba encontrarme a mi llegada a los Ángeles,

Jon, el periodista, no se andaba por las ramas ni cambiándole el significado a

las palabras. Como era un intelectual sin ninguna pretensión de serlo, llamaba a

las cosas por su nombre. La lucha de clases era simplemente eso y los

principales protagonistas de sus relatos eran los obreros y los burgueses

capitalistas, la humanidad y el imperio, la justicia y la injusticia, la verdad

y la mentira. En realidad, era una suerte para cualquier revista contar con un

colaborador como Hillson. Nunca le pagamos un centavo. Escribía simplemente por

su fe en que sus denuncias podían ayudar a mejorar el mundo.

En esa

misma convicción, la defensa de Cuba tenía un lugar destacado. Hillson, quien

desde que estudiaba allá por mediados de los años 60 en una escuela secundaria

en las cercanías de la ciudad de Nueva York se había iniciado como activista

político, se convirtió en un apasionado partidario de la Revolución cubana tras

leer el ensayo del Che Guevara El hombre y el socialismo en Cuba.

Cuba no

solo aparecía en sus artículos o en las continuas actividades que organizaba en

Los Ángeles a favor de la Isla, sino que su ejemplo le servía para su misión

como sindicalista en el aeropuerto. Tenía tan presente a Cuba en su prédica

sindical que sus compañeros de trabajo le replicaban en tono de sorna:

“¡Cállate, Fidel! ¡Cállate, cubano!” Siempre al servicio de la Revolución, sus

últimas actividades a favor de Cuba estuvieron relacionadas con la lucha por la

libertad de los Cinco Héroes cubanos prisioneros del imperio, así como por los

derechos de los norteamericanos de viajar a la Isla. Su última estancia en La

Habana, fue como organizador de una delegación de un centenar de jóvenes

norteamericanos deseosos de conocer, por ellos mismos, la realidad cubana.

La última

vez que nos vimos fue en el portal del Palacio del Segundo Cabo. “Cuando vuelvas

—le dije a modo de despedida—, nos vamos con Beverly a dar una vuelta por los

carnavales”. “No me gustan”, aseguró. “Ya verás que sí —insistí—, tú no sabes

nada de eso”.

Casi una

semana antes de su muerte, justo dos días antes de salir yo para Venezuela, me

llamó por teléfono, como solía hacer casi todos los viernes, para preguntarme si

había leído un correo que me había enviado con algunas consideraciones suyas

sobre la intelectualidad liberal norteamericana. No había tenido tiempo de

leerlo, pero de todas formas hablamos como 20 minutos sobre las próximas

elecciones, los posibles candidatos demócratas y el acto que estaban preparando

para combatir las nuevas restricciones de la actual administración para impedir

los viajes a Cuba. Me dijo que participaría en un acto donde hablaría el

traductor de tailandés de Bush recientemente sancionado por viajar a la Isla.

“Un buen tipo”, agregó. Mencionó también una manifestación que sería la más

grande de todos los tiempos que se realizaría en Los Ángeles y en donde, de

alguna manera, estarían presentes los Cinco. Como siempre, le pedí que me

mandara un buen trabajo sobre todo eso. Después, le pregunté para cuándo volvía.

“Para el 26 de marzo, dijo, viajaré en la última delegación con licencia”.

La muerte

le impidió el regreso para esa fecha. Pero si como yo creo Jon Hillson está

leyendo estas líneas en alguna parte, sabe, también como yo, que regresará

nuevamente a la Isla el día que las barreras del engaño dejen de ser el

obstáculo que impide consumar la amistad de nuestros pueblos.

http://www.lajiribilla.cu/2004/n144_02/144_32.html

FROM

KATHLEEN KELLY

NY TRANSFER NEWS

Jon Hillson was a talented poet and

journalist whose work was always enthusiastically received by our readers. He

was also a tireless and steadfast revolutionary whom we all admired for his

energy and commitment. Jon's death is a loss to the Cuba solidarity movement and

the US struggle for peace and social justice. He left us much too soon, and he

will be greatly missed.

Kathleen Kelly

Editorial Director

NY Transfer News

http://www.blythe.org

e-mail: nyt@blythe.org

The

following links provide a small sample of Jon's many talents and

interests, as published by NY Transfer News over the last few years:

His The

Sexual Politics of Reinaldo Arenas essay on the film "Before

Night Falls" is a piercing commentary on the sexual politics of

Reynaldo Arenas and a compassionate analysis of the history of Cuban

social policy after the revolution. When the World Trade Center was

attacked on Sept 11, 2001, Jon wrote Blowback

Blues (a poem)

Jon

covered a wide variety of issues as a journalist, from foreign policy to

the struggles for labor rights and civil liberties in the US. Here

are just a few examples:

CELEBRATING

THE LIFE OF JON HILLSON

Program for the Hillson Memorial Meeting

Los Angeles, California - March 7, 2004

here

WELCOME:

Beverly Truemann

CHAIRPERSON:

Thabo Ntweng

Los Angeles airline worker and longtime friend

SPEAKERS:

Betsey

Stone

Socialist Workers Party

L.A. Coalition in Solidarity with Cuba

Paula

Solomon

Co-coordinator, Los Angeles Coalition in Solidarity with

Cuba

Messages from Cuba and South Africa

Geoff

Mirelowitz

Seattle railroad switchman and friend for over 30 years

Ted

Hillson and Deb Kissinger

Brother and sister-in-law

Aaron

Ruby

Translator, friend and political collaborator

since meeting Jon in Nicaragua in 1983

Dr.

Marjorie Bray

Coordinator, Latin American Studies Program

California State University, Los Angeles

Eddie

Torres

LA co-coordinator, U.S.-Cuba Youth Exchange 2003

Youth and the Future Seminar 2004

Pasquale

Lombardo - Dana Markiewicz

Immigrant rights lawyer & activist

Latin American historian and interpreter

Oriel

Maria Siu

Steering Committee, Youth and the Future Seminar

(Havana, Cuba March 2004)

William

Chavez

Steering Committee, Youth and the Future Seminar

(Havana, Cuba March 2004)

Updated April 29, 2005

home

Jon

Hillson spent his entire adult life active in the struggle for a better

society, a socialist society. We first met in the 1970s, when we were both

members of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States. He was a

journalist, a trade unionist and a revolutionary socialist activist. Here

you will find a broad selection of Hillson's writings, and of the many tributes to and observations

which have come out about his life and activities.

Jon

Hillson spent his entire adult life active in the struggle for a better

society, a socialist society. We first met in the 1970s, when we were both

members of the Socialist Workers Party in the United States. He was a

journalist, a trade unionist and a revolutionary socialist activist. Here

you will find a broad selection of Hillson's writings, and of the many tributes to and observations

which have come out about his life and activities.

From left to right: Jon Hillson,

From left to right: Jon Hillson,

Jon

Hillson y Beverly, su esposa y

Jon

Hillson y Beverly, su esposa y