Latin

American Polítics

The historic dilemma of the Cuban Revolution

Torn between its far-reaching eagerness to deal out liberty and the meagerness of its geography, the Cuban Revolution remains the touchstone of a Latin American wave of popular fervor poised to take over and duty-bound to reach higher levels.

On January 1st the Cuban

revolution celebrated its fiftieth anniversary. Not bad at all,

especially if we bear in mind that it’s been hounded since day one, by

the hyperpower of the North no less. It’s worth mentioning as well that

very few revolutions, if any, have managed to set such a radical, albeit

realistic, tone for so long. There’s been, no doubt, some stagnation and

increasing bureaucratization, let alone the fact that the fate of the

26th of July Movement is still closely linked to the lives of its

surviving founders, but the example of integrity set by the Revolution

and its long-standing effort to educate the overall Cuban society are

likely to preserve the essence of that spirit when time gets its revenge

and neither Fidel nor Raúl Castro are no longer around.

On January 1st the Cuban

revolution celebrated its fiftieth anniversary. Not bad at all,

especially if we bear in mind that it’s been hounded since day one, by

the hyperpower of the North no less. It’s worth mentioning as well that

very few revolutions, if any, have managed to set such a radical, albeit

realistic, tone for so long. There’s been, no doubt, some stagnation and

increasing bureaucratization, let alone the fact that the fate of the

26th of July Movement is still closely linked to the lives of its

surviving founders, but the example of integrity set by the Revolution

and its long-standing effort to educate the overall Cuban society are

likely to preserve the essence of that spirit when time gets its revenge

and neither Fidel nor Raúl Castro are no longer around.

The Cuban Revolution is a landmark in Latin America’s history. As stated before, it sprang from a mistake: the United States’ assumption that those young university students who had dug themselves in the Sierra Maestra mountains were, formally speaking, good democrats and therefore akin to any other petit bourgeois kids always willing to look askance at corrupt regimes, but ready to take in the perquisites that power brings with it. Self-deception went both ways. Those who came in the Granma yacht believed in the values of radical democracy and their chance to use them to change the world. Otherwise, the U.S. would have made sure to tighten up on them rather than let them run on a free rein or even receive, from Florida and Central America, the shiploads of weapons held by Washington to have served to topple a dictator whose depravity had turned him into an uncomfortable partner. As both the State Department and the CIA, Batista’s replacement by a bunch of radical youths could be, like in past occasions, a manageable event.

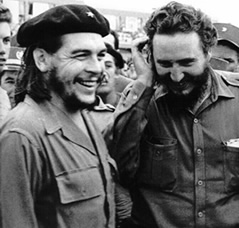

However, contrary to what usually happens when ‘young people mount a horse from the left side and dismount on the right’, everything turned out to be different. The civil war experience and the implementation of the agrarian reform fueled principles these youths had already grasped by then: the need for a drastic change to solve Cuba’s social problems. Such avenging convictions joined forces with a nationalism spurred by endless U.S.-bred humiliation throughout their country’s ‘independent’ history and the evidence that only by expropriating U.S. property and boosting in-depth agrarian reforms could the goals set by the Castro brothers, Che Guevara et al. be attained.

Trouble broke out right away. Anti-revolution propaganda across the U.S. media, together with the escape of Cuban bourgeois landowners and businessmen –who believed with almost absolute certainty that their American buddies would crush that mob of madmen in no time– were just a foretaste of a string of actions to undermine the regime, the most notorious of which were the bombing of a ship loaded with arms bound for the island and the Bay of Pigs invasion.

It was the onset of a period marked by uncertainty and harassment that defined the whole revolutionary era and exposed the dilemma we are dissecting here.

Great ambitions boiled in the Cuban Revolution’s caldron. For all its original desire to transform its own society, its strong resemblance to many other Latin American processes hinted that its example could be quite contagious. Awareness of this fact among the powers that be –and especially in the mind of the Argentinean doctor Ernesto Guevara, who had become the Army’s second-in-command and the Revolution’s most inspiring figure after Fidel Castro– opened up a wide range of possibilities which both lit a fire under many youths in the continent and urged Washington to put it out. Expelled from the OAS and abandoned to its fate by governments across Latin America in the wake of the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Revolution had to find a way out. The ideological formation of its leadership and the current state of affairs –at the height of the cold war– made Cuba lean toward the communist bloc and the consequences that such a move entailed for decades to come.

This evolution, however, took place in stages defined in principle by Washington’s deep-set ill will toward the new regime. When Cuba proceeded to expropriate U.S.-owned companies and make a land reform without giving in exchange anything the Americans could call ‘fair compensation’, their decision to stop buying Cuban sugar threw the island’s economy off balance. But then the USSR stepped forward to buy the same sugar quota at preferential prices and pay with oil, badly needed in Cuba since the suspension of fuel shipments it used to receive from the U.S. and Venezuela.

Given the North’s resolve to strangle the Revolution –as indicated by repeated attacks from offshore, treacherous actions to destroy our crops, infiltrations of Florida-based guerrilla groups and assassination attempts on Fidel, Cuba had no choice but to swing to the Eastern bloc. And since the aggression was real, why not take such step and equip ourselves with a missile shield capable of deterring the U.S. from attacking us? To do anything of the sort you need assistance from a partner whose interests you should take into consideration, so much so if the said partner carries a lot of weight in the world’s political arena, like the USSR did in the early 60s. The missile crisis in 1962 came up not so much the result of Cuba’s wish to protect itself from its northern enemy as it was the result of the Soviet strategists’ conclusion that the deployment of nuclear warheads in the island could prompt the U.S. to remove their own [similar] military bases from Turkey. It was a parley held on a knife-edge where Cuba had little or no say.

All in all, the game ended with a part public, part secret trade: in line with the former, the USSR would withdraw its bases from Cuba in return for the United States’ pledge not to invade the island, while the latter was the real quid pro quo: within the following six months, the Americans would dismantle their military bases in Turkey.

Realpolitik and Revolution

Accepting the demands of realpolitik was a bitter blow for the Cuban leaders, divided on the tack their relations with the Soviet Union had taken –not from a practical viewpoint perhaps, as they were all well aware that the revolutionary phenomenon had little or no chance to survive unless it joined the socialist bloc– with some of them adapted, if a bit reluctantly, to the new realities and others willing to try other solutions. Leaked rumors have it that the fossil-like, bureaucracy-ridden, small-minded Soviet regime was especially rejected by Che, who advocated the search for options to save the premises that inspired the Revolution in the first place, that is, a swell-like force bound to spread like wildfire across a continent yet to be redeemed but capable of doing an about-face similar to Cuba’s. Fidel Castro himself had flagged the precept of this current when he said, “May the Andes become Latin America’s Sierra Maestra”, and plenty of attempts were made in the 1960s and part of the 1970s to make good on his words.

When political action runs on something more than just opportunism and personal profit, knowledge of history becomes paramount. What happened in those years, therefore, must be clear to us so that we can evaluate whether liberation is possible in Latin America and how far should the action for change go to achieve it, without losing sight of the fact that, even if the continent has only one body, its limbs may not necessarily be equally mobile at all times. Robespierre said that a revolution cannot be imposed at the point of bayonets, and he knew very well what he was talking about.

Right from the start the Cuban revolution bumped into a key problem: the existing contradiction between the ambition –or hope, if you like– of its followers and the smallness of its venue, an imperiled, isolated land exposed to relentless harassment by the Northern colossus. A mostly agricultural island with slender economic resources and a small population, Cuba was hardly able to extend its influence to the rest of a continent, caught as it was in the maelstrom of the Cold War and the clutches of an economy dominated by imperialism.

There was no way to solve the problem with the help of its Soviet ally, whose intention was precisely to put all anti-imperialist movements into an orbit outside the path of Russia’s foreign policy. Nevertheless, their alliance was of essence if Cuba wanted to be relatively safe from the U.S. menace and count on the energy and industrial resources it needed to carry out on its own soil a social search-and-rescue program like the one set in motion with great success five decades ago in fields such as public health and education.

The need to find ways to overcome this obstacle conditioned the whole Cuban experience. Both Fidel Castro and Che Guevara had set their hopes on a Latin American revolution that would yank Cuba out of isolation, much like Lenin, Trotsky and Bolsheviks expected Russia would no longer be a backward state once the October Revolution reached Germany first and the rest of Europe afterward. Neither did, although we have to admit that at least Cuba paid a much lower price, thanks both to the size of the testing ground and the moderate and –in the final analysis– open of these societies, saved in no small degree by their ductility and usual disorder from the somber legacy of revolutions we have seen in powerful countries built on a past of either feudal oppression or totalitarianism.

Be that as it may, the Cuban leaders’ awareness of the need to break the walls around the island and reach out to the continent testifies to their grit and backbone as well as their grasp of the fact that their own revolution was a constituent element of the Latin American one. Still, never in the heyday of the revolutionary process did their strategic wit managed to find the tactical means required to field-test their beliefs. Che remains as much the best example of such a sound strategic insight as he does of a tactical failure that placed limits on the heroic years of the Cuban experience, and at a very high price to boot.

Stifled by the burden of the U.S. blockade and the Russian bear hug, the Cuban leaders groped for something they could pin their hopes on and stumbled upon the ‘focus theory’, French writer Regis Debray’s brainchild. He had come to the island wearing the hat of a progressive intellectual who commits to foreign causes because he’s not quite sure to have one of his own, and spread a project sprung from the objective needs of the Cuban experiment rather than from the mind of a leftist resolved to find a long-coveted ‘good revolutionary’ image in a place he found exotic. But then again, it was more about designing policies fit for the middle and lower strata of our societies –considering their past as well as their distinctive features– than the will of leaders pumped up by their Sierra Maestra stunt, a victory owed, as we said before, to a monumental mistake. You can put up a revolution using a universal formula no more than you can boil it down to a militarism given by its very nature to dampen or utterly shut out public sectors conscious that the said method has failed in their own countries if industrial capitalism has flourished there, deformed though its progress may have been. Change by force of arms is only possible –if at all– within a decaying society in dire need of that kind of surgical renovation.

The adventure

Nonetheless, the experiment was put into practice, mostly encouraged by Che. In theory, it involved planting a guerrilla force within difficult reach of the regular army wherefrom they could get increasing support from a long-starving, humiliated peasant population forced to serve the local landowners and put up with their abuse. The idea was a real flop: it failed everywhere except in Colombia, where there already was a well-established peasants’ guerrilla. Che Guevara, the first who tried to put together a core of rebels in Bolivia, was gunned down shortly after by CIA-trained Bolivian Rangers; the priest Camilo Torres Restrepo, pioneer of liberation theology, shared a similar fate in Colombia; and all remaining attempts to organize a rural guerrilla fell through one after the other.

Ernesto Guevara’s choice of Bolivia as the first target and his devotion to the venture bear witness to his heroism and strategic talent, but also to his shortcomings as a theorist of Latin American revolution. Bolivia is indeed a focal point of South American geopolitics, but… it had just finished an agrarian reform! Biased, spineless and cheating as it may have been, the leaders of the National Revolutionary Movement (MNR) had made it not too long after the epic 1952 uprising, and the peasants were not looking forward to joining the call to fight. Consequently, the guerrilla was soon left to its own devices and cornered in the middle of the jungle until the bitter, and unavoidable, end.

Guevara was dead, but not his theory, which other youths picked up to try and introduce it in urban areas where they could take advantage of the cloak of anonymity and chances to go unnoticed that big cities provide, not to mention the banks waiting to be robbed, the ransoms they could get from kidnappings, and the funds that a number more or less significant of sympathizers would be happy to give them. But the outcome was no different but for the level of violence that relocating the theater of operations entailed, with guerrilla actions as stealthy and bloody as the brutal crackdowns on them by indigenous armed forces not exactly lacking in steel, unlike the out-and-out ‘national guards’ the United States had set up the length and breadth of the Caribbean.

The extreme left-wing feelings of the above guerrilla groups and their political wings caught on quickly among a youth imbued with France’s May events in a sort of city-based insurrection of anarchic and ludic persuasion which fanned out as an activism with a clear military slant to it as soon as it was moved over to a setting where social relations were a lot more troublesome than in Europe. They jumped onto the growingly strong popular bandwagon that was gaining momentum at that time –mainly in Argentina and Chile– only to undermine those currents from the inside, causing their division and thus giving the right wing parties a long-awaited excuse to unleash a repressive force backed by the U.S., overwhelmingly superior from a military point of view, and largely unquestioned by popular sectors who were either oblivious to, stunned by or scornful of subversion. That’s how a baleful period of dirty war began which put paid to the continent’s already feeble ability to stand up to unrestrained capitalism, a primary attribute of neoliberal globalization.

No country escaped the slaughtering, and two generations passed by before Latin America did anything to get rid of the neoliberal walrus. Nowadays things are a far cry from what prevailed in the 60s and 70s, when the revolutionary project sponsored by Cuba dared set its sights on Utopia. There’s no bipolar world anymore, and to many people’s surprise, the implosion of the USSR did not mark the end of the Cuban revolution. Quite the opposite: after a ‘special period’ of transition to the new circumstances, Castro’s regime seems to have strengthen its hold on things and, what’s even more important, all indications are that its message has struck a major chord among the Latin American masses. Needless to say, even though people’s claims for social equality and demands for sovereignty preexisted the Cuban revolution, neither the original project devised in the island nor the resolve of its leaders to set it in motion have fallen on stony ground. There’s a complicated situation out there today, and the future is likely to have anything in store from opportunities to drawbacks. And even if the island can’t –or won’t– play a predominant role in the course of events, it’s not alone anymore: Cuba is now a member of the Rio group, and various governments somehow acknowledge its status as a precursor whose spirit, after so many battles, has escaped the insular enclosure and landed on Terra Firma.

January 4, 2009.

---ooOoo---

A CubaNews translation.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Thanks to Nestor Gorojowski for bringing this article to my attention.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|