| |

|

Frida from

Cuban art

By Sussette Martínez Montero

Fine Arts Promoter

Friday, July 20, 2007

A CubaNews translation by Sue Greene.

Edited by Walter Lippmann.

Frida is the woman-universe

and the multiple concept chosen as reference point for this tribute exhibition.

Being conceived from a gender perspective allows an interesting dialog

among the works of 50 artists.

A

myth reaches 100 years and the esteemed Benito Juárez Casa de las

Americas (Office of the Havana City Historian) has opened its doors to

mark it. It is the tribute of 50 Cuban artists who, from different

artistic manifestations,

decorate the place with their works, joining those throughout the entire

world, they pay tribute to the centennial of Frida Kahlo. A

myth reaches 100 years and the esteemed Benito Juárez Casa de las

Americas (Office of the Havana City Historian) has opened its doors to

mark it. It is the tribute of 50 Cuban artists who, from different

artistic manifestations,

decorate the place with their works, joining those throughout the entire

world, they pay tribute to the centennial of Frida Kahlo.

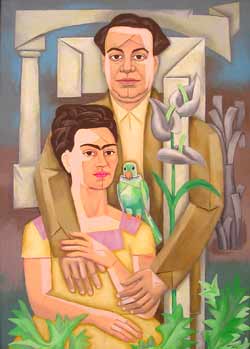

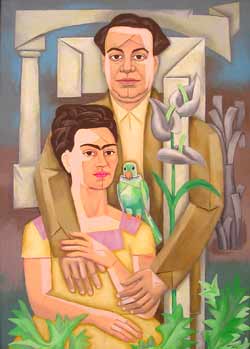

This collective show is integrated into the event program "Frida and

Diego, Voices from the Earth", as a way to pay tribute to these top

figures of Latin American art and culture, in the year marking the

centenary of Frida Kahlo and the half-century of Diego Rivera's death.

This event is sponsored by Casa de las Americas, the Pablo de la

Torriente Brau Cultural Center and the Mexican Embassy in Cuba.

Others have already done it. The muse of their creations and the sound

of heels have become portrayal and song. It precedes the appearance of

young girls, who with scented petals receive Frida Azul Celeste who

ascends magnificently, opening the doors of the exhibition.

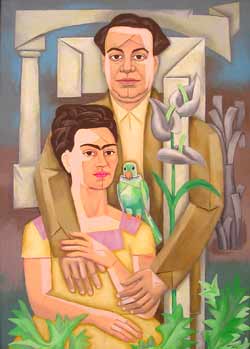

"From Eve's skin, with Adam's eyes" is the title of this exhibition

which consists of two exhibition rooms in that museum: 24 women and 26

men, with the multiplicity of discourses which has characterized the

fine arts of this island in recent decades. They bring their vision near

the figures of Frida and Diego, which by a curious dirty trick of fate,

remain united, even after death. The coincidence is accurate because

Frida is also Diego, and she is, at the same time, his mother, his

lover, his student and his accomplice. For him, reinventing herself,

creating herself as legend, recovering the traditional image of a

Mexican woman. Diego is light and strength, and her joy for living and

her deepest pain. For this muralism giant, she will be the refuge after

the storm, understanding without limit, "an exceptional artist, and the

best proof of the rebirth of art in Mexico".

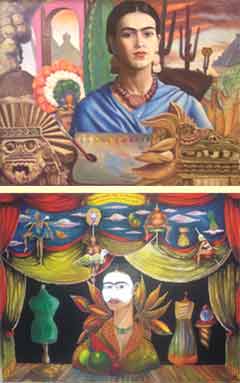

Brilliant and tragic like her own history, the work of Frida marked a

turning point in twentieth-century Latin American artistic endeavor. It

established norms on subjects such as self-portraiture and the identity

of our people. Her paintings and her writings are a lacerated and

exquisite autobiography, in which artistic endeavor becomes exorcism

against adversity, demystification of death and acts of faith.

With a recommendation placing it

right in the middle of both exhibitions, the show opened with the

performance Written on the Skin, conceived by Manuel López Oliva

along with the The Enchanted Deer theatrical group. It became an evocative

bridge of meaning between the strong and suggestive movement of the

nude actress (Lorelis Amores) with band-aids on parts of her body,

which were recalling the lacerations of Frida, and the projection (by

means of a show across time) of some 4O textures derived from works of

the painter López Oliva. They not only functioned as painted

clothing of the famous figure and her surroundings, but through her

state of virtual tattoos, they converted her skin into a base for

imprinting poetic equivalences of decorative weave and life symbolism:

pleasure and pain, tragedy and the distinctive discourse of the universal

Mexican artist.

Frida is the solitary woman-universe and the multiple concept chosen as the

exhibition reference point. But the fact of being conceived from a gender perspective

allows an interesting dialogue between the works of both exhibition

rooms, where the pieces of this tribute exhibition are on display. In

the Adam's eyes, Frida is image and example, history and artwork. An

indissoluble whole which the artists have brought forth from their own

languages.

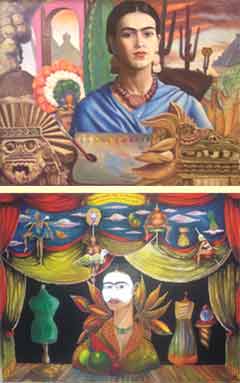

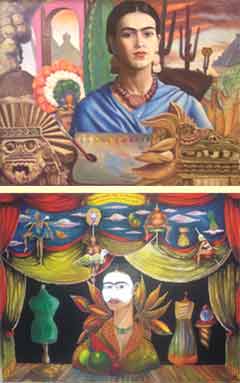

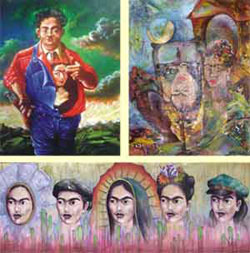

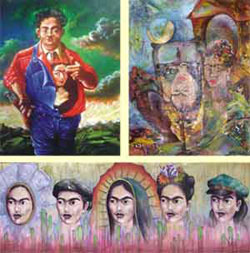

Many of the artists use the portrait as a path for homage (Adigio

Benítez, Sinecio Cuétara, Guillermo Zaldívar, Ignacio Nazábal and Emilio

Nicolás), but even in this supposed homogeneity, each gives us who is

their Frida.

Sometimes it is the complete face, others only the united eyebrows,

becoming iconic representation, the center of the composition which is

completed with elements alluding to Mexico, the pyramids, the flag or

Rivera himself. While in other cases, such as the work of Carlos Reyes,

the portrait is used as part of a strategic discourse from the very

concept of that which represents Frida, obtaining an image of the

transvestite artist in symbols of universal culture.

Another

aspect handled in a more pluralistic manner in the exhibit is pain,

inevitably linked to Frida, and a recurring element in her own work. The

idea of physical and spiritual laceration has two representations in

this case, which still have as a basis the postmodern concept of

appropriation, addresses it from a more integrated dimension. In

Pá

Focusing Yourself on Life, by Eduardo Yanes, he convinces the

metaphor, achieved with an artistic structure which shares the

same factual conception as the work. Using, at the same time, skilled

resources and abstract expressionism, he superimposes significantly

charged elements which confer to it an unquestionable anthropological

spirit. On the other hand, Fridaqui, exhibit by Onelio Larralde,

transcends the appropriation of "The Broken Column" in order to

establish a proposition for identification, which, through a mirror,

forces the visitors to penetrate, in our century, the martyred body of

"Saint Sebastian". Another

aspect handled in a more pluralistic manner in the exhibit is pain,

inevitably linked to Frida, and a recurring element in her own work. The

idea of physical and spiritual laceration has two representations in

this case, which still have as a basis the postmodern concept of

appropriation, addresses it from a more integrated dimension. In

Pá

Focusing Yourself on Life, by Eduardo Yanes, he convinces the

metaphor, achieved with an artistic structure which shares the

same factual conception as the work. Using, at the same time, skilled

resources and abstract expressionism, he superimposes significantly

charged elements which confer to it an unquestionable anthropological

spirit. On the other hand, Fridaqui, exhibit by Onelio Larralde,

transcends the appropriation of "The Broken Column" in order to

establish a proposition for identification, which, through a mirror,

forces the visitors to penetrate, in our century, the martyred body of

"Saint Sebastian".

But these are not the only cases in which appropriation becomes a

pretext for re-reading of the same work. William Hernández and Vincent

R. Bonachea, notable for the way in which they trained, starting with

the self-portrait, they succeed in converging their thematic and

methodical reasoning with the aesthetic suppositions of the work of

Kahlo.

For their part, works like that of Agustín Bejarano, Ángel Rogelio

Oliva, Julio Velázquez, Michel Mirabal, Regis Soler and Nelson Domínguez

establish, from an assumed distance, a very comprehensive conceptual

dialog which touches themes such as sexuality, faith and the feminine

stereotypes in which Frida was accustomed to being situated.

However, our Eves achieve, in this case, a common result of greater

conceptual coherence. They

address us from their own skin, in a more intimate dialog, because Frida

is intimately addressing us, person to person, as a woman and as

an artist.

It's impossible to fail to note, then, accomplishments like, With

Affection from the Voice of Experience, by Cirenaica Moreira; Of

Dreams and Stigmas, by Marta María Pérez; Inner Traps, by Lidzie

Alvis; "The Favorite", by Mabel Llevat or "Encounters", by Aimée

García, who, with a strong gender vein from self-portrait photographs,

they leave clearly established the force that the Frídico legacy has in

contemporary female artistic endeavor. While, for their part, Alicia de

la Campa, Lesbia Vent Dumois, Ileana Mulet, Aziyadé Ruiz and Hortensia

Margarita Guash, accomplish it with painting, establishing an identity

bridge with the most sensitive work of the Mexican artist.

Taking some of tools from the craft's resources traditionally allocated

to feminine endeavors, Virginia Menocal, Mayra Alpízar and Nilda

Margarita Rojo, masterfully prepare their discursive presentations, from

techniques such as tapestry, embroidery and "patchwork", respectively.

Using these methods, the first two establish a confrontation between the

depth of discourse and the delicacy of materials used. Meanwhile, Nilda

does it from her demonstrated mastery of appropriations. And in

sculpture, Isabel Santos from crude wax recreates the game with death

that Rivera immortalized in the mural exhibited at the Prado hotel in

the Mexican Federal District.

With the audacity that is born from an older approach, Sandra Dooley

receives them at her house in Santa Fe, while Eidania Pérez and Lourdes

León makes use of caricature in "Tree of Hope, Maintain Yourself

Steadfast", irreverent and ongoing work, in which Frida and Diego

are rescued from their political position, placing them in the midst of

an event with Cuban flags, without leaving out the touch of acrid humor

that necessarily accompanies this genre. They emphasize the sensual and

"public" play of the couple. In precise counterpoint, Yossiel Barroso

captures the Mexican reality of today, with a snapshot, taken from the

Zócalo Museum of Fine Arts, in which centenarian Frida, attends the

event Mexico's gay community holds every year on this date in the

Federal District. Frida is inserted in our present, the present is seen

by Frida. Undoubtedly, a unique visual approach.

But if this were not enough, Beatriz Santacana takes on again the

Mexican votive offerings with a mixture of irony and posthumous tribute.

Her Frida gives thanks for saving her lover from the hands of Diego: her

Diego thanks the Virgin that "Doña Frida has agreed

to see the world again together", thereby achieving a very suggestive

proposition in which the rescue of popular traditions converges with the

reinvention of history. And Liudmila López, true to her style,

metaphorizing by means of a pair of shoes both -masculine and feminine-

unequal and indissoluble. But, missing in this ensemble, an

indispensable look: the Frida of ample blouse and

shawl, of braided crown in arabesque, of jingling bracelets and

rings, the "Frida Fashion" which scandalized the streets of New York and

Paris with the attire of the Mexican indigenous and became the

inspiration for the model Madame Rivera de Elsa Shiaparelli. It is the

proud Frida which dominates her typical image, as righteous defense of

the ancestral culture of our people of America, where modernity

threatens to destroy them. The Frida on the cover of Vogue, which

Zaida del Río now reclaims in her performance exhibit with Ismael de la

Caridad. From her jewelry and her femininity without limits, Frida is

depicted, Frida remains, Frida is blue, black, white and green:

polychrome y fascinating as her own life.

Frida multiplied a thousand and one times, before by herself, and now by

others who have seen her example, an icon of feminism, a hope against

pain, an incentive for joy, a powerful artistic reality, a legend. Frida

of America, and therefore also, of Cubans, from these 50 artists who

have united their work to pay tribute to her, from Eve's skin and with

Adam's eyes.

(This text was expressly requested by its author, who in addition,

was responsible for curating the exhibition tribute to the Mexican

artist Frida Kahlo which, on July 6, 2007, was inaugurated in the

Esteemed Benito Juárez Casa de las Americas. It may be visited until

August 31.)

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

La Habana,

julio 20

de 2007

|

|

|

|

|

http://www.opushabana.cu/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=728&Itemid=44

|

Frida desde el arte

cubano

Por: Sussette

Martínez Montero, Promotora de artes plásticas..

viernes, 20 de julio de 2007

Frida es la mujer-universo y el concepto

múltiple elegido como referente de esta muestra homenaje.

El hecho de estar concebida desde una perspectiva

genérica permite un diálogo interesante entre las obras

de 50 artistas.

Un

mito cumple 100 años y la Casa del Benemérito de las

Américas Benito Juárez (Oficina del Historiador) ha

abierto sus puertas para celebrarlo. Es el homenaje de

50 artistas cubanos que desde diferentes manifestaciones

de la plástica engalanan el lugar con sus obras, para

unirse a los que en el mundo entero rinden tributo al

centenario de Frida Kahlo. Esta muestra colectiva se

integra al programa del evento

«Frida y Diego, voces de la tierra», un modo de

tributarle a estas figuras cumbres del arte y la cultura

latinoamericanos, en el año del centenario de Frida

Kahlo y el medio siglo de la muerte de Diego Rivera.

Este evento cuenta con el auspicio de la Casa de las

Américas, el Centro Cultural Pablo de la Torriente Brau

y la Embajada de México en Cuba. Un

mito cumple 100 años y la Casa del Benemérito de las

Américas Benito Juárez (Oficina del Historiador) ha

abierto sus puertas para celebrarlo. Es el homenaje de

50 artistas cubanos que desde diferentes manifestaciones

de la plástica engalanan el lugar con sus obras, para

unirse a los que en el mundo entero rinden tributo al

centenario de Frida Kahlo. Esta muestra colectiva se

integra al programa del evento

«Frida y Diego, voces de la tierra», un modo de

tributarle a estas figuras cumbres del arte y la cultura

latinoamericanos, en el año del centenario de Frida

Kahlo y el medio siglo de la muerte de Diego Rivera.

Este evento cuenta con el auspicio de la Casa de las

Américas, el Centro Cultural Pablo de la Torriente Brau

y la Embajada de México en Cuba.

Ya otros lo han hecho. La gráfica y la canción la han

convertido en musa de sus creaciones y en sonido de

tacones. Precede a la aparición de las niñas, que

reciben con pétalos perfumados a una Frida Azul Celeste

que asciende magnífica para abrir las puertas de la

exposición.

«Desde la piel de Eva, con los ojos de Adán» es el

título de esta exhibición que abarca dos salas de esa

casa museo: 24 mujeres y 26 hombres, con la

multiplicidad de discursos que ha caracterizado a la

plástica de esta isla en las últimas décadas, acercan su

visión a las figuras de Frida y Diego, que por una

curiosa jugarreta del destino permanecen unidos, aún

después de la muerte. Acertada coincidencia porque Frida

es también Diego, y es a un tiempo su madre, su amante,

su alumna y su cómplice. Para él se reinventa, se crea a

sí misma como leyenda, recuperando la imagen tradicional

de la mujer mexicana. Diego es luz y fuerza, y su

alegría de vivir y su dolor más hondo. Para este gigante

del muralismo ella será el refugio tras la tormenta, la

comprensión sin límite, «una artista excepcional, y la

mejor prueba del renacimiento del arte en México».

Genial y trágica como su propia historia, la obra de

Frida marcó un antes y un después en el quehacer

artístico latinoamericano del siglo XX, estableciendo

pautas en temas tales como el autorretrato y la

identidad de nuestros pueblos. Sus cuadros y sus

escritos son una lacerante y exquisita autobiografía, en

el que el quehacer artístico deviene exorcismo contra la

adversidad, desacralización de la muerte y acto de fe.

Con una propuesta que lo ubica justo al centro de los

dos discursos, la muestra abrió con el performance

Escrito sobre la piel, concebido por Manuel López

Oliva junto al grupo teatral El Ciervo Encantado. Llegó

a establecerse un puente evocador de sentido entre la

fuerte y sugerente gestualidad de la desnuda actriz (Lorelis

Amores) con esparadrapos sobre partes del cuerpo que

rememoraban laceraciones de Frida, y la proyección (mediante

un data show) de unas 4O texturas derivadas de obras del

pintor López Oliva, que no sólo funcionaban como

vestiduras plásticas de la figura y su contorno, sino

que por su condición de tatuajes virtuales convertían a

la piel en un soporte para estampar equivalencias

poéticas del tramado decorativo y el simbolismo vital:

el placer y el dolor, la tragedia y el discurso

distintivos de la universal artista mexicana.

Frida es la mujer-universo única y el concepto múltiple

elegido como referente de la exposición. Pero el hecho

de estar concebida desde una perspectiva genérica

permite un diálogo interesante entre las obras de ambas

salas, donde se exhiben las piezas de esta muestra

homenaje. Para los ojos de Adán, Frida es imagen y

ejemplo, historia y obra. Un todo indisoluble que los

artistas han trabajado desde lenguajes propios.

Muchos de los artistas utilizan el retrato como vía para

el homenaje (Adigio Benítez, Sinecio Cuétara, Guillermo

Zaldívar, Ignacio Nazábal y Emilio Nicolás), pero aún en

esta supuesta homogeneidad, nos entrega cada quien

su Frida.

Unas veces es el rostro completo, otras sólo las cejas

unidas, devenidas representación icónica, centro de la

composición que se completa con elementos alusivos a

México, las pirámides, la bandera o el propio Rivera.

Mientras que en otros casos, como en la obra de Carlos

Reyes, el retrato es usado como parte de un discurso

estratégico desde el concepto mismo de lo que Frida

representa, obteniéndose una imagen de la artista

trasvestida en símbolos de la cultura universal.

Otra

de las aristas manejadas de manera más plural en la

muestra es el dolor, irremediablemente ligado a Frida, y

elemento recurrente en su propia obra. La idea de

laceración física y espiritual tiene en este caso dos

representaciones, que aún teniendo como base el

posmoderno concepto de las apropiaciones, discursan

desde una dimensión más integradora. En Pá fijarte a

la vida, de Eduardo Yanes, convence la metáfora

lograda con una estructura plástica que parte de la

misma concepción factual de la obra. Utilizando a un

tiempo recursos artesanales y del expresionismo

abstracto, sobrepone elementos cargados de significantes

que le confieren un indiscutible espíritu antropológico.

Por su parte Fridaqui, instalación de Onelio

Larralde, trasciende la apropiación de La columna

rota para erigirse propuesta de identificación que,

a través del espejo, obliga a los visitantes a penetrar

en el cuerpo martirizado de la «San Sebastiana» de

nuestro siglo. Otra

de las aristas manejadas de manera más plural en la

muestra es el dolor, irremediablemente ligado a Frida, y

elemento recurrente en su propia obra. La idea de

laceración física y espiritual tiene en este caso dos

representaciones, que aún teniendo como base el

posmoderno concepto de las apropiaciones, discursan

desde una dimensión más integradora. En Pá fijarte a

la vida, de Eduardo Yanes, convence la metáfora

lograda con una estructura plástica que parte de la

misma concepción factual de la obra. Utilizando a un

tiempo recursos artesanales y del expresionismo

abstracto, sobrepone elementos cargados de significantes

que le confieren un indiscutible espíritu antropológico.

Por su parte Fridaqui, instalación de Onelio

Larralde, trasciende la apropiación de La columna

rota para erigirse propuesta de identificación que,

a través del espejo, obliga a los visitantes a penetrar

en el cuerpo martirizado de la «San Sebastiana» de

nuestro siglo.

Pero no son estos los únicos casos en los que la

apropiación deviene pretexto para la relectura de una

obra propia. William Hernández y Vicente R. Bonachea

destacan por la adiestrada manera en la que, partiendo

del autorretrato, logran hacer converger su discurso

temático y formal con los presupuestos estéticos de la

obra de la Kahlo.

Por su parte, obras como la de Agustín Bejarano, Ángel

Rogelio Oliva, Julio Velázquez, Michel Mirabal, Regis

Soler y Nelson Domínguez establecen, desde una supuesta

distancia, un diálogo conceptual muy abarcador que toca

temas tales como la sexualidad, la fe y los estereotipos

femeninos en los que Frida acostumbraba a ubicarse.

No obstante, nuestras Evas consiguen, en este caso, un

resultado común de mayor coherencia conceptual.

Discursan desde su propia piel, en un diálogo más íntimo,

pues Frida es tratada de tú a tú, como mujer y como

artista.

Imposible dejar de señalar, entonces, realizaciones como

Con Cariño de la voz de la experiencia, de

Cirenaica Moreira; De Sueños y estigmas, de

Marta María Pérez; Trampas del interior, de

Lidzie Alvisa; La Favorita, de Mabel Llevat o

Encuentros, de Aimée García, quienes con una

fuerte veta de género desde la fotografía

autorreferencial, dejan claramente establecida la

vigencia que el legado frídico tiene en el

quehacer artístico femenino contemporáneo. Mientras que,

por su parte, Alicia de la Campa, Lesbia Vent Dumois,

Ileana Mulet, Aziyadé Ruiz y Hortensia Margarita Guash,

lo hacen desde la pintura, estableciendo un puente

identitario con la parte más sensible del trabajo de la

artista mexicana.

Tomando como herramientas algunos de los recursos

artesanales tradicionalmente asignados al quehacer

femenino, Virginia Menocal, Mayra Alpízar y Nilda

Margarita Rojo, elaboran con maestría sus propuestas

discursivas, desde técnicas tales como el tapiz, el

bordado y el patchwork, respectivamente. Se

establece así, en las dos primeras, un enfrentamiento

entre la profundidad del discurso y la delicadeza de los

materiales utilizados. Mientras, Nilda lo hace desde su

demostrado dominio de las apropiaciones. Y en la

escultura, Isabel Santos desde la cera cruda recrea el

juego con la muerte que Rivera inmortalizara en el mural

expuesto en el hotel del Prado del mexicano Distrito

Federal.

Con la osadía que nace de un mayor acercamiento, Sandra

Dooley los recibe en su casa de Santa Fe, mientras que

Eidania Pérez y Lourdes León echan mano de la caricatura

en Árbol de la esperanza, mantente firme, obra

desacralizadora y actual, en la que Frida y Diego son

rescatados desde su posición política, al situarlos en

medio de una manifestación con banderas cubanas, sin

dejar fuera el toque de humor picante que necesariamente

acompaña a este género. Ellas enfatizan en el jugueteo

sensual y «público» de la pareja. En justo contrapunteo,

Yossiel Barroso capta la realidad mexicana de estos días,

con una instantánea desde la que una Frida centenaria,

tomada del Zócalo del Museo de Bellas Artes, asiste

complacida a la manifestación que cada año por esta

fecha celebra en el Distrito Federal la comunidad gay

mexicana. Es Frida insertada en nuestra actualidad, la

actualidad vista por Frida. Sin dudas, un peculiar

enfoque visual.

Pero si esto fuera poco, Beatriz Santacana retoma los

exvotos mexicanos con una mezcla de ironía y homenaje

póstumo. Su Frida da gracias por salvar al amante de las

manos de Diego: su Diego agradece a la Virgen que «Doña

Frida haya aceptado volver a ver el mundo juntos», con

lo cual logra una propuesta muy sugerente en la que

convergen el rescate de las tradiciones populares y la

reinvención de la historia. Y Liudmila López, fiel a su

estilo, los metaforiza a ambos mediante un par de

zapatos –masculino y femenino– desigual e indisoluble. Mas,

falta a este conjunto una mirada indispensable: la Frida

de huipil y rebozo, de corona trenzada en arabescos, de

pulseras y anillos tintineantes, la Frida Fashion que

escandalizó a las calles de Nueva York y París con el

atuendo de las indígenas mexicanas y devino inspiración

para el modelo Madame Rivera de Elsa Shiaparelli. Es la

Frida altiva que impone su imagen típica, como justa

defensa de la cultura ancestral de nuestros pueblos de

América, cuando la modernidad amenaza con destruirla. La

Frida de la portada de Vogue, que Zaida del Río

rescata ahora en su instalación performática con Ismael

de la Caridad. Desde sus joyas y su feminidad sin

límites, Frida pinta, Frida permanece, Frida es azul,

negra, blanca y verde: polícroma y fascinante como su

propia vida. Mas,

falta a este conjunto una mirada indispensable: la Frida

de huipil y rebozo, de corona trenzada en arabescos, de

pulseras y anillos tintineantes, la Frida Fashion que

escandalizó a las calles de Nueva York y París con el

atuendo de las indígenas mexicanas y devino inspiración

para el modelo Madame Rivera de Elsa Shiaparelli. Es la

Frida altiva que impone su imagen típica, como justa

defensa de la cultura ancestral de nuestros pueblos de

América, cuando la modernidad amenaza con destruirla. La

Frida de la portada de Vogue, que Zaida del Río

rescata ahora en su instalación performática con Ismael

de la Caridad. Desde sus joyas y su feminidad sin

límites, Frida pinta, Frida permanece, Frida es azul,

negra, blanca y verde: polícroma y fascinante como su

propia vida.

Frida multiplicada una y mil veces, antes por ella misma,

y ahora por otros que han visto en su ejemplo un icono

del feminismo, una esperanza contra el dolor, un

aliciente para la alegría, una poderosa realidad

artística, una leyenda. Frida de América, y por ende

también, de los cubanos, de estos 50 artistas que han

unido su obra para rendirle tributo, desde la piel de

Eva y con los ojos de Adán.

(Este texto fue solicitado expresamente a su autora,

quien además, tuvo a su cargo la curaduría de la

exposición homenaje a la artista mexicana Frida Kahlo

que, el 6 de julio de 2007, quedó inaugurada en la Casa

del Benemérito de las Américas Benito Juárez. Hasta el

31 de agosto podrá ser visitada). |

|

Sussette Martínez Montero

Promotora de artes

plásticas.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A

myth reaches 100 years and the esteemed Benito Juárez Casa de las

Americas (Office of the Havana City Historian) has opened its doors to

mark it. It is the tribute of 50 Cuban artists who, from different

artistic manifestations,

decorate the place with their works, joining those throughout the entire

world, they pay tribute to the centennial of Frida Kahlo.

A

myth reaches 100 years and the esteemed Benito Juárez Casa de las

Americas (Office of the Havana City Historian) has opened its doors to

mark it. It is the tribute of 50 Cuban artists who, from different

artistic manifestations,

decorate the place with their works, joining those throughout the entire

world, they pay tribute to the centennial of Frida Kahlo.  Another

aspect handled in a more pluralistic manner in the exhibit is pain,

inevitably linked to Frida, and a recurring element in her own work. The

idea of physical and spiritual laceration has two representations in

this case, which still have as a basis the postmodern concept of

appropriation, addresses it from a more integrated dimension. In

Pá

Focusing Yourself on Life, by Eduardo Yanes, he convinces the

metaphor, achieved with an artistic structure which shares the

same factual conception as the work. Using, at the same time, skilled

resources and abstract expressionism, he superimposes significantly

charged elements which confer to it an unquestionable anthropological

spirit. On the other hand, Fridaqui, exhibit by Onelio Larralde,

transcends the appropriation of "The Broken Column" in order to

establish a proposition for identification, which, through a mirror,

forces the visitors to penetrate, in our century, the martyred body of

"Saint Sebastian".

Another

aspect handled in a more pluralistic manner in the exhibit is pain,

inevitably linked to Frida, and a recurring element in her own work. The

idea of physical and spiritual laceration has two representations in

this case, which still have as a basis the postmodern concept of

appropriation, addresses it from a more integrated dimension. In

Pá

Focusing Yourself on Life, by Eduardo Yanes, he convinces the

metaphor, achieved with an artistic structure which shares the

same factual conception as the work. Using, at the same time, skilled

resources and abstract expressionism, he superimposes significantly

charged elements which confer to it an unquestionable anthropological

spirit. On the other hand, Fridaqui, exhibit by Onelio Larralde,

transcends the appropriation of "The Broken Column" in order to

establish a proposition for identification, which, through a mirror,

forces the visitors to penetrate, in our century, the martyred body of

"Saint Sebastian".

Mas,

falta a este conjunto una mirada indispensable: la Frida

de huipil y rebozo, de corona trenzada en arabescos, de

pulseras y anillos tintineantes, la Frida Fashion que

escandalizó a las calles de Nueva York y París con el

atuendo de las indígenas mexicanas y devino inspiración

para el modelo Madame Rivera de Elsa Shiaparelli. Es la

Frida altiva que impone su imagen típica, como justa

defensa de la cultura ancestral de nuestros pueblos de

América, cuando la modernidad amenaza con destruirla. La

Frida de la portada de Vogue, que Zaida del Río

rescata ahora en su instalación performática con Ismael

de la Caridad. Desde sus joyas y su feminidad sin

límites, Frida pinta, Frida permanece, Frida es azul,

negra, blanca y verde: polícroma y fascinante como su

propia vida.

Mas,

falta a este conjunto una mirada indispensable: la Frida

de huipil y rebozo, de corona trenzada en arabescos, de

pulseras y anillos tintineantes, la Frida Fashion que

escandalizó a las calles de Nueva York y París con el

atuendo de las indígenas mexicanas y devino inspiración

para el modelo Madame Rivera de Elsa Shiaparelli. Es la

Frida altiva que impone su imagen típica, como justa

defensa de la cultura ancestral de nuestros pueblos de

América, cuando la modernidad amenaza con destruirla. La

Frida de la portada de Vogue, que Zaida del Río

rescata ahora en su instalación performática con Ismael

de la Caridad. Desde sus joyas y su feminidad sin

límites, Frida pinta, Frida permanece, Frida es azul,

negra, blanca y verde: polícroma y fascinante como su

propia vida.