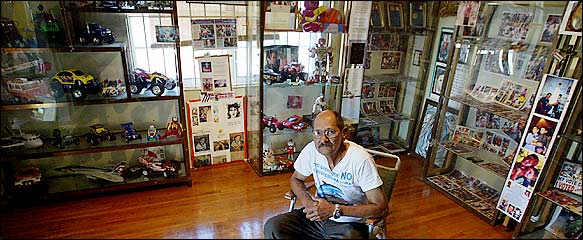

Alex Quesada for the New York Times

Delfin Gonzalez, a great-uncle

of Elián González,

has turned the Miami house Elián lived in into a

museum.

|

Alex Quesada for the New York Times

Delfin Gonzalez, a great-uncle

of Elián González, |

![]()

Published: January 28, 2005

![]() IAMI,

Jan. 27 - The moment - 5:14 a.m. on April 22, 2000 - remains as vivid to them as

yesterday. Armanda Santos was fixing her daughter a drink in the predawn quiet

of their kitchen. Carmen Valdes was praying the rosary. Leslie Alvarez was

eating a slice of pizza, and Madeleine Peraza was holding vigil with friends in

her living room.

IAMI,

Jan. 27 - The moment - 5:14 a.m. on April 22, 2000 - remains as vivid to them as

yesterday. Armanda Santos was fixing her daughter a drink in the predawn quiet

of their kitchen. Carmen Valdes was praying the rosary. Leslie Alvarez was

eating a slice of pizza, and Madeleine Peraza was holding vigil with friends in

her living room.

The calm - and for years to come, they said, their well-being - was shattered when federal agents with long guns descended on NW Second Street in Little Havana, swarming a small white house and snatching a boy named Elián González. Now, almost five years after the government seized Elián from his great-uncle's home and returned him to his father in Cuba, neighbors and others who witnessed the three-minute raid are getting their day in court.

In a civil trial that began Monday in federal court here, 13 plaintiffs are seeking up to $250,000 each in damages, charging that agents from the Immigration and Naturalization Service unnecessarily sprayed them with tear gas at close range, shoved, cursed and traumatized them in their zeal to remove Elián without a struggle. Government witnesses have testified that the officers used only appropriate and necessary force as they made their way through a gantlet of furious protesters to reach Elián.

Though the world, even most of Miami, has put the Elián affair in the past, the plaintiffs say they relive it constantly. In testimony this week, they described being sprayed in the face with tear gas and still suffering depression, anxiety, sleeplessness.

"I could not breathe, my face was burning," said Ms. Alvarez, a plaintiff who did not live on the street but had gone there that morning, she said, to show support for the Gonzalez family. "I thought I was going to die, and something has remained with me."

Several of the plaintiffs said they still gather at poolside barbecues, in one another's kitchens or in front of Casa Elián, as it is known here, to recall how Elián, then 6, entered and departed their lives. He was found floating alone in an inner tube off the Florida coast on Thanksgiving Day in 1999, after his mother and 10 others drowned as they tried to cross from Cuba.

His great-uncle in Miami, Lazaro Gonzalez, took him in, but Elián became an international obsession - the subject of a political tug of war between Fidel Castro, who demanded the boy's return to his father in Cuba, and his relatives and other Cuban exiles here, who said returning him would be crushing to democracy. Many of the family's supporters, including Ms. Alvarez and Ms. Valdes, had gathered that morning behind barricades that the police had erected outside the Gonzalez house.

Others, including neighbors like Mrs. Peraza and Mrs. Santos, had stayed up all night in their houses waiting for the showdown they had heard was coming, though they had no idea when or in what form. Some plaintiffs testified that agents went onto their property to spray tear gas, while others said they were sprayed in the face while standing behind the barricades. Several said they initially thought Mr. Castro had sent the black-suited, helmeted agents to wreak havoc on their neighborhood.

Nancy Canizares, another plaintiff, who lives in Hialeah, Fla., but said she visited Elián's neighborhood regularly back then, said she was sitting in a lawn chair on the sidewalk behind the Gonzalez home when agents jumped from a van and shouted, "Don't move, don't move, I'll kill you." She said they forced her to lie face down on the ground with her legs spread, even after she told them she was in pain.

The suit, filed in 2003, originally had more than 100 plaintiffs, but most were dropped after Judge K. Michael Moore of United States District Court ruled that only people who stayed off the Gonzalez property and behind the barricades that morning were eligible.

Government witnesses said on Thursday that the agents never encroached on the plaintiffs' property, and that those who sprayed gas did so only when protesters began surging toward the barricades and throwing rocks and other objects at them.

"The crowd was very animated and angry and started to breach that barricade line," said Michael Compiatello, an agent who said he sprayed gas during the raid but only from a distance.

The nonjury trial is expected to wrap up on Friday.

As his drama is reborn in a courtroom here, Elián Gonzalez, now 11, is living a cloistered but still highly publicized life in the small town of Cárdenas, Cuba. Children across the island celebrate his birthday each December. He appears at political rallies with Mr. Castro and is said to have bodyguards who escort him to and from school.

Elián lives with his father, Juan Miguel, his stepmother and two younger half brothers. His American relatives have not seen or spoken to him since the raid, though they predict he will return to them one day.

"When Elián grows up, he will come back and see this house," said Delfin Gonzalez, another of Elián's great-uncles, who bought the house after the raid. Delfin Gonzalez turned the house into a museum, which he said people visit every week to see Elián's toys, clothes and race-car bed.

Delfin Gonzalez said he lived for a time in the Florida Keys but was drawn back to the little white house even though its silence weighs on him. Lazaro Gonzalez and his daughter, Marisleysis, left the neighborhood after the raid to escape memories and reclaim their anonymity, Delfin Gonzalez said. They return sometimes, but Ms. Gonzalez, now 26, never enters the house, he said.

Reached at the hair salon she opened several years ago, Ms. Gonzalez, who acted as a mother to Elián when he lived here, declined to be interviewed. The family has its own lawsuit pending against the agents in the raid, said Irene Garcia, a spokeswoman for Judicial Watch, a conservative group that brought the suit being heard this week.

A judge ruled that the agents had immunity, Ms. Garcia said, but the family has appealed. The family and neighbors and bystanders also tried to sue Janet Reno, President Bill Clinton's attorney general, who ordered the raid. Those suits were dismissed when the courts ruled that Ms. Reno had immunity.

Donato Dalrymple, who found Elián drifting at sea during a fishing trip, was originally a plaintiff in the suit being heard this week. But he was dropped because he was inside the Gonzalez house during the raid. Mr. Dalrymple famously hid with Elián in a closet, then tried to hold on to the screaming boy as an armed agent pulled him away.

Ms. Santos, 69, who lives two doors down from the Gonzalez house, said she was not sure how she would spend any money won in the suit. She is just happy to be involved, she said, even if testifying was her most unnerving experience since the raid.

"I have my right," she said. "And if I have my right, why not take advantage of it?"

Terry Aguayo contributed reporting from Miami for this article.